“The way that sharps and flats are organised is far from random or chaotic”: How to understand key signatures

If you thought that using the right key was just about getting through your front door, we’ve got some indispensable info for you!

Take a look at some form of musical score, you will notice that at the beginning of every line, there are a collection of signs made up of either hash-tag signs, or lowercase letter b’s (unless of course you are in the one key that does not use either of these!)

This collective of squiggles is known as a 'key signature'. The hash-tags(#) are known as sharps, whereas the letter 'b’s' are known as flats (b), but why do we have them?

If you have read our previous article on the construction of scales, you will know that each scale conforms to a sequence of tones and semitones. The adoption of a key signature acts as a form of shorthand, meaning that you don't have to keep writing sharps and flats throughout your piece. If you have a F# in your key signature, every you time you play the note F you should play F# instead, by default.

The way that these sharps and flats are organised is far from random or chaotic. We won't get too technical here, but suffice to say that the sharps and flats appear in a specific order, and sharps and flats are never combined in the same key signature.

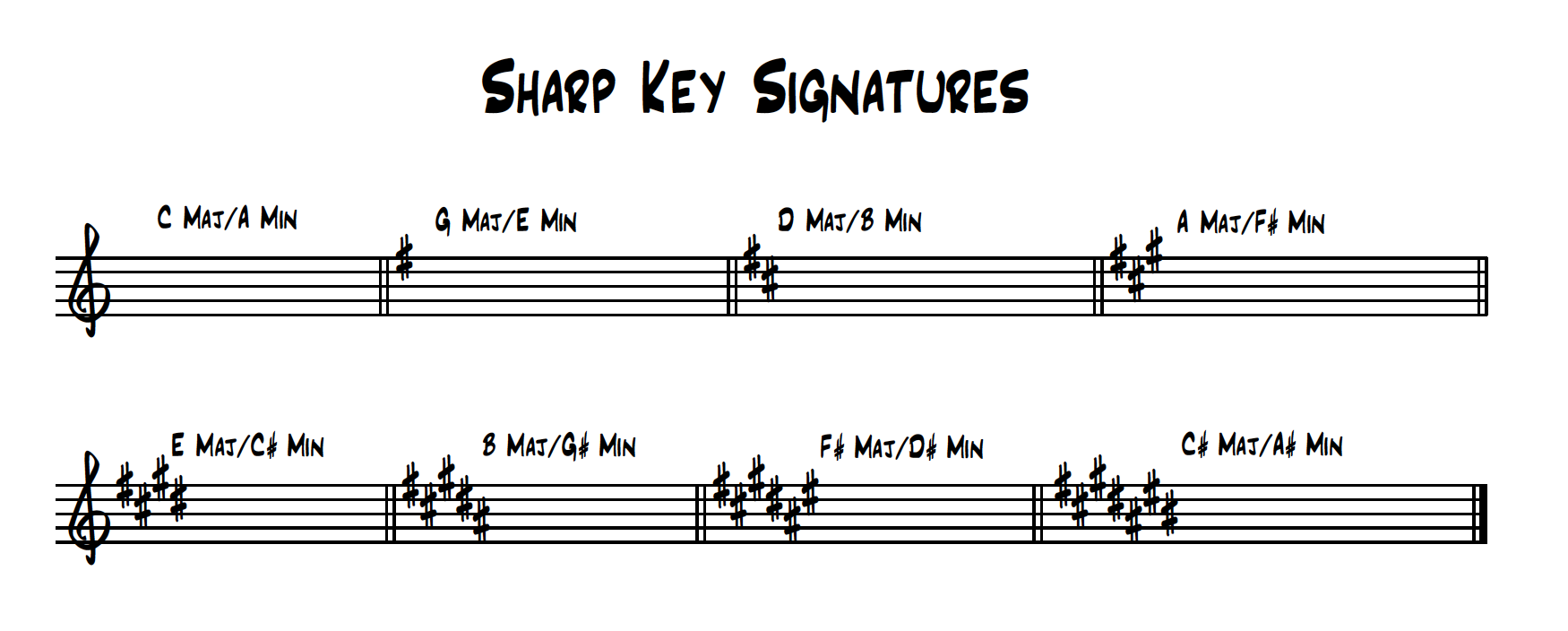

Sharp key signatures

We have to mention C major as an outlier. It does not contain any sharps or flats, hence any piece of music in C major will not have a key signature, as it is not required. On a practical level, many keyboard players like C major, as there are no black notes to play.

The number of sharps in a key signature increases, as we move through what is known as ‘the cycle of 5ths'. Count up five notes from the note C, and you get to G - G major contains 1 sharp.

Count up another five notes, and you get to the note D - D major contains 2 sharps. Continue this process through the cycle of fifths, to A, E, B, F# and C#, the last of which contains 7 sharps in the key signature.

If you regularly work with guitarists, it is important to note that they prefer working in sharp key signatures. Keys such as E and A major resonate with guitarists, as they reflect the tuning of the instrument.

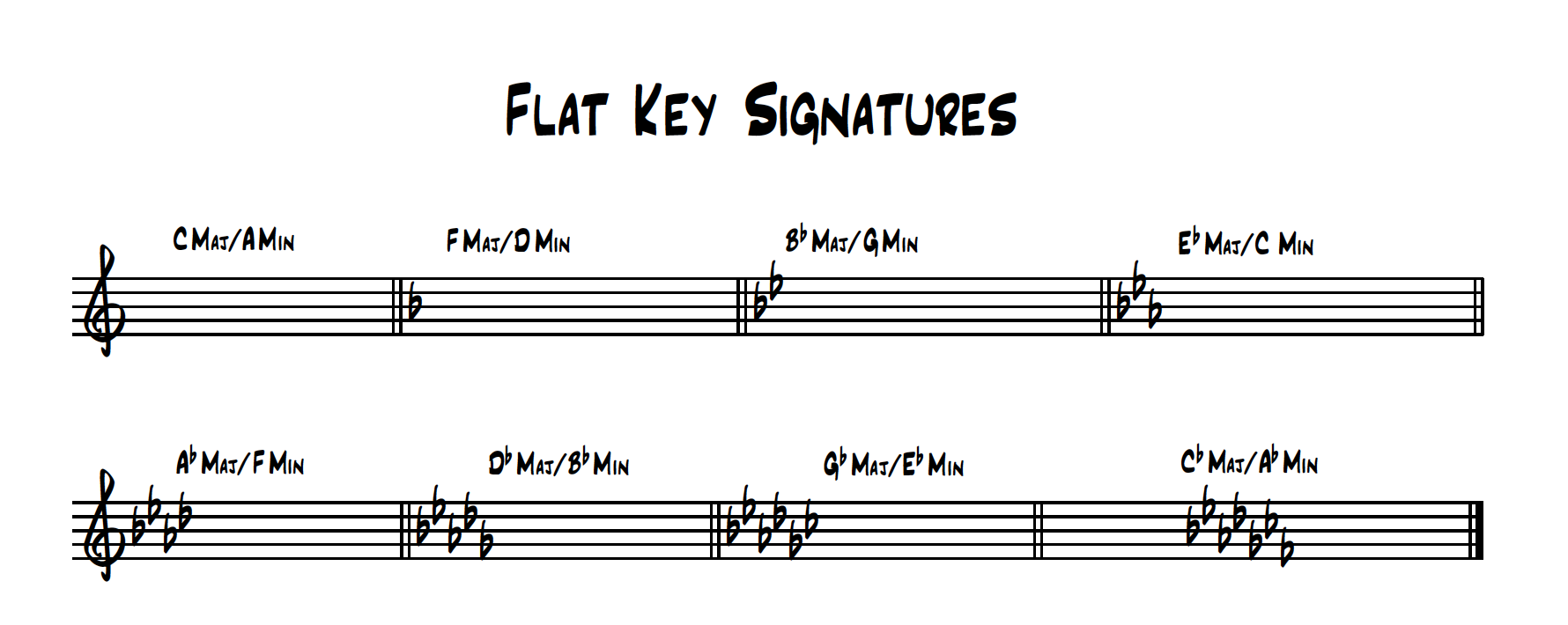

Flat key signatures

If you follow the same ‘cycle of 5ths’ rationale and count downwards by five notes, you reel off the flat keys. F major has one flat, Bb has two, and so on, through Eb, Ab, Db, Gb and Cb.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Much like guitarists with sharp key signatures, flat key signatures are the preference for brass instruments such as trumpets and trombones, as well as some woodwind instruments. Many of these instruments are tuned naturally on the flat side, hence they can be easier to play in these keys.

Theory of relativity

You may have noticed that so far we have only mentioned major keys; every key signature reflects two keys: a major version, and the more melancholic minor relative.

You can work out the relative minor of a major key by simply counting down three semitones. For example, C major (with no key signature) is relative to A minor (also with no key signature). Follow this process through and E major (4 sharps) is relative to C# minor. Bb major (2 flats) on the other hand, is relative to G minor.

As sharps and flats in a key signature are written on the corresponding lines and spaces of the clef and stave that you are using, there are two handy rhymes that are helpful for reminding you of the order of each.

Take the first letter of each word, as the sharp in question, and use ‘Frederick Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle’. (F# C# G# D# A# E# B#). It’s also handy to know that if you reverse the order of the rhyme, using the same words, this becomes the order of the flats, in a flat key signature; ‘Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles Frederick’. (Bb Eb Ab Db Gb Cb Fb).

Read the previous instalments in our ongoing theory series below

- The pillars of music theory made simple

- How to become a master of melodies

- A quick guide to reading music

- How to understand rhythm when reading music

- Learning and understanding scales

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK