“The verse and chorus of that song are exactly the same. But, you don’t really notice since the energy of the chorus is completely different”: Cracking open Max Martin’s über-succesful songwriting formula

Exploring the winning routes taken by the songwriting mastermind behind Britney Spears, Katy Perry and Ariana Grande's biggest tunes

Despite being one of popular music’s most prolific songwriters (it’s likely you’ll be familiar with at least 90% of his body of work) the name Max Martin still only really resonates with those keen on the intricacies of songwriting. For those in the know, it's a name that is synonymous with crafting ‘perfect’ pop.

Tracks penned (or co-penned) by the Swedish songsmith tend to sell and stream phenomenally well. They also serve to underscore the qualities of the artists themselves.

Notable examples include Britney Spears’ iconic breakthrough, Baby One More Time or the Backstreet Boys’ first single We’ve Got it Goin' On (and the group's ensuing salvo of boyband-defining hits). Examples that prove how Martin is an adroit judge of which songs will fit each artist. Then, tirelessly working to get the best from the vocal performers he’s working with.

When looked at it in closer detail, Martin’s best songs also offer us something of a blueprint for ultra-effective pop songwriting.

Max's skillset is something that all music-makers can learn from. Even those not aiming at the charts themselves.

Just a cursory glance at his songbook proves the point, from the best performing output of the Backstreet Boys (Everybody, I Want it That Way etc) to Katy Perry’s anthemic Roar, Kelly Clarkson's monster 2004 smash Since U Been Gone all the way up to, arguably, Taylor Swift’s most pop culturally resonant hits - Shake it Off and Blank Space.

It's clear that Martin has a Midas touch, borne out of decades of experience.

But, as with all the greatest music, what makes his songwriting really WORK so well is not just one tactic in isolation.

Martin is well aware that finely tuning the elements that constitute a great pop song takes time and graft - akin to designing a luxury ocean liner from the ground up.

Though Max tends to shy away from interviews and stating too prescriptively how he writes, he has shared many insights into his songwriting approach across the years.

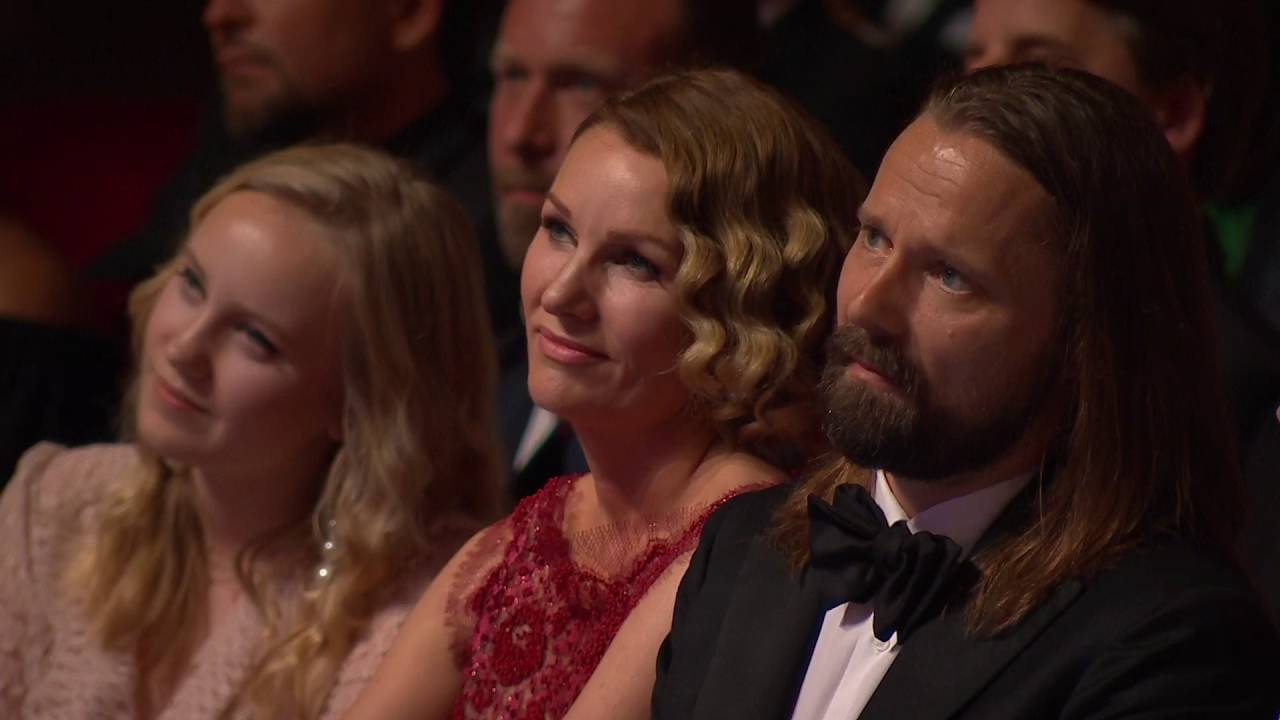

The most fascinating came in the wake of his winning the Polar Music Prize back in 2016, speaking to Jan Gradvall for an on-camera masterclass, and an in-print interview in Swedish financial newspaper, Dagens Industri.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In these conversations, Max spoke about how he wrote and assembled some of the biggest pop songs of all time. He also gave some fascinating commentary on the songwriting process to Q With Tom Power’s podcast

Understanding the centrality of melody

A common thread in Max Martin’s commentary on his songwriting is the fundamental importance of melodies - both top-lines and counter.

He has also shared that approaching melody writing first - prior to any chord sequence and prior to any arrangement (or vibe-based) considerations can lead to an ultimately more versatile and mobile motif that can be drawn upon repeatedly throughout the song.

To that end, the chorus melody can repeat the same melody as the verse, albeit within the context of a changed ‘energy’ (more dense instrumentation, harder hitting beats and a fatter vocal mix).

A good example is in the Backstreet Boys' I Want it That Way, where the small melodic shape of the verse ('you are, my fire, the one desire') is also called upon for the central chorus motif of 'I want it that way').

Max explained why this works in his conversation with Jan Gradvall, “You can also sing the chorus melody as a verse. For instance, take ‘I Wanna Be Your Lover’ with Prince. The verse and chorus of that song are exactly the same. But as a listener, you don’t really notice since the energy of the chorus is completely different compared to the verse. Once the chorus comes, you feel like you’ve heard it before. And you have!”

What Max has described as ‘melodic math' underlines the importance of melody. But really, this oft-repeated phrase boils down to just trying to tune into the psychology of the listener in relation to the overall arrangement.

As Max stated in the above quote, he's a master of building up anticipation and that feeling of familiarity in the listener by tactically, almost subtly, revealing melodies that reveal themselves later in new shapes. It's so clever it's almost subliminal.

Another aspect of this lay in how the interweaving relationships between an initial melody and a secondary melody can create captivating and pulsing rhythmic dynamics.

A good example of this is Britney’s Baby One More Time, which is defined by its staccato melody and Spears’ on-the-beat delivery. The core idea here is built around simplicity but maximum impact.

The song defines its melody clearly and essentially stamps itself into the minds of listeners.

Lyrics should be built entirely in support of the melody

There’s also the oft-pointed out use of particularly strange phrasing and grammar across Max’s work.

Just consider the oddness of the title of Britney’s aforementioned debut (which humorously stemmed from some confusion around ‘hit me up’ and ‘call me up’). Then, there's Robyn’s Show Me Love, wherein the Swedish future pop titan sings “You’re the one that I ever needed” and Ariana Grande’s “Now that I’ve become who I really are.”

The reason these grammatical oddities remained uncorrected is because of their importance to the ‘sound’ of the melody.

“To me, phonetics really matter,” Max told Tom Power in 2023. “There’s a big part of the world where [the listener] does not speak English. These songs are massive in those countries. My theory is about how it sounds and how it makes you feel when you hear these words. ABBA is a great example of that [when you think of] Mamma-Mia or Money Money Money. Even if you don’t understand it, it felt good to me.”

So, the importance of how words sound trump what they’re actually saying.

The lyrics should accentuate and serve to push forward the peaks and valleys that the melody scales. These lyrics should be intrinsically tied to the melody.

Martin stresses the importance of keeping that melodic line basic if you’re placing it in a more intense context. “If you’ve got a verse with a lot of rhythm, you want to pair it with something that doesn’t. Sweet and salt might be a description that’s easier to grasp. You need a balance, at all times. If the verse is a bit messy, you need it to be less messy right after” [Taylor Swift’s] Shake it Off is a good example.

Is it a song or is it a movie?

Martin thinks of a song in the same way as a film, and considers each element to reflect a character.

As with a film, Martin emphasises that giving each element space to be introduced is vital for not over-loading your listener with too much information.

“There shouldn’t be too much information in the overall sound,” Martin explained. “I work a lot on getting it all as clear and distinct as possible. There should never be too many new elements introduced at the same time. One at a time. Like in a movie. You can’t introduce ten characters in the first scene. You want to get to know one before you’re ready for the next”

It's Max' view, then, that melodies - like protagonists and supporting characters - return for those key moments. Their familiarity spelt out by their preceding prominence in the arrangement. It all adds to a feeling of heroic resolution.

A core Max Martin mantra is that a song should be immediately recognisable - something he has stressed at numerous points throughout his career. Inspired by the instant recognition to the next track cue'd up by the DJ in the club world.

The importance of those critical first three seconds are perhaps even more essential to get right when you consider the ever depleting concentration spans of consumers.

Max also stresses that a song should serve up a stew of hooks; “You must be able to have more than one favourite part in the same composition. First out, you might like the chorus. Then, once you’ve grown a little tired of that you must long for the bridge”

The bridge and chorus Martin’s songs was analysed in the Q podcast, where the host notes that after or in lieu of the bridge, there’s typically a repetition of the chorus section with a different meter and a different melody, he cites Oops!… I Did it Again and I Want it That Way as an example.

“I can’t remember how we came up with that concept." Max continues, "It was an attempt to not bore the listener. The trick was that it had to match - that you could put them together and play [the original melody] at the same time. That totally works - you can just put them on top of each other.”

That sense of familiarity in the listener is a vital concern, and all this repetition of the various characters and identities should culminate in a grand finale, often marked by a key change or the introduction of more instrumentation; “I like it when a song is like a journey, building up along the way. That they start out smaller than they end. Along the trip, you should add elements that make the listener less likely to tire. Then, at the end, euphoria.”

While there's a lot more to unpack when it comes to Max Martin's songwriting approach, the heart of all of it really does come down to this principle of taking the listener on a journey into the song and leaving them anticipating those big, flagship moments.

Viewing the song as a film certainly helps in this regard, as can the idea of the top-line melody as a central character.

Thinking of music-making in this way can help you to break out of a 'songwriting' mindset, and more settle more into understanding the psychology of mass appeal.

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“How daring to have a long intro before he’s even singing. It’s like psychedelic Mozart”: With The Rose Of Laura Nyro, Elton John and Brandi Carlile are paying tribute to both a 'forgotten' songwriter and the lost art of the long song intro

“The verse tricks you into thinking that it’s in a certain key and has this ‘simplistic’ musical language, but then it flips”: Charli XCX’s Brat collaborator Jon Shave on how they created Sympathy Is A Knife