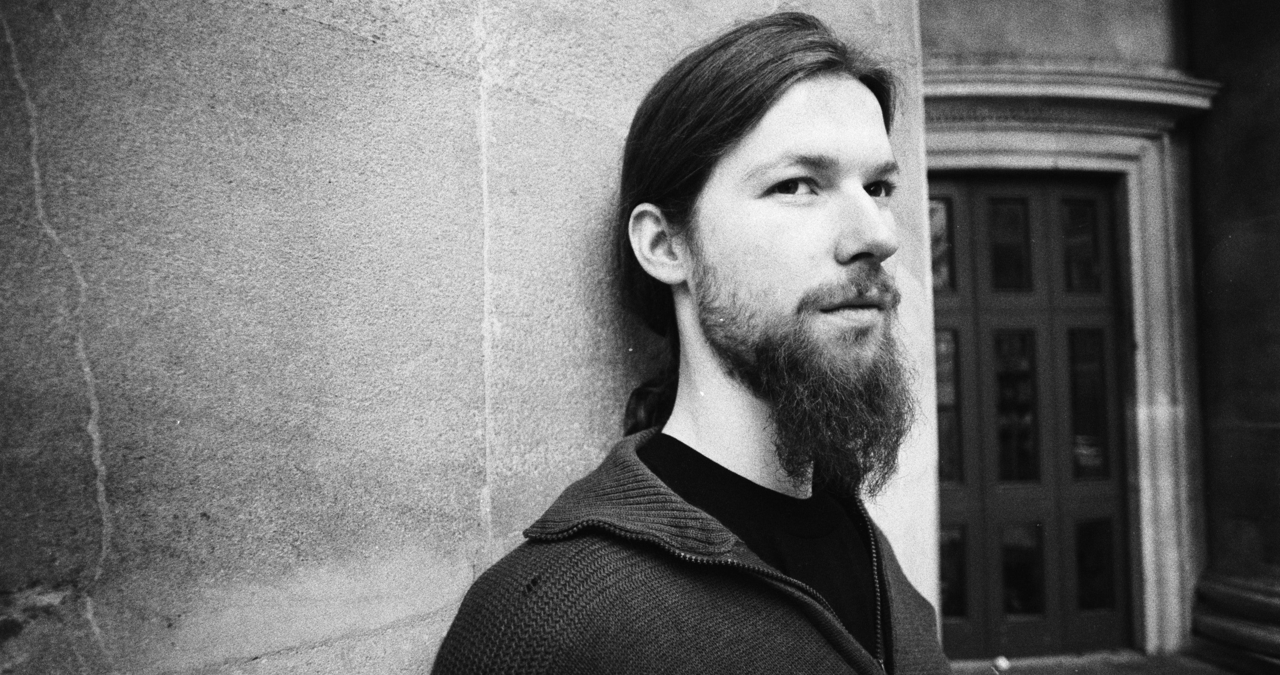

“The risk is that I never finish a piece - I want to push them further, to see how far they can be deformed without tearing”: How Aphex Twin fought the temptation to continually refine, and how we can learn from his example

It’s easy to carry on fiddling with our tracks, but as Richard D. James knows all too well, that urge to keep going can prove a problem

How exactly do you know when a track is finished? It’s the one question that we most consistently find ourselves asking artists when speaking to them in interviews. It’s an enquiry borne out of genuine curiosity. When do you walk away and say 'it's done'?

For years we’ve sat on abandoned projects, half-formed demos and ‘nearly-finished’ pieces that we just can’t quite get over the line. In the 2020s, with even greater tinkering options on the table, that anxiety around closing the book on a project has only been heightened.

With the limitless scope and creative possibilities of DAWs, instruments, effects and the perpetual EQ massaging we can apply to our work, stepping away and marking any one track as a finished piece can often make us feel like we’ve jumped the gun.

When it comes down to it, a large fear is that we will feel that niggle upon completion, that perhaps, the difference that would have lifted the track into the big leagues was just about to be landed on…if only we’d worked on it for slightly longer.

For the uniquely explorative work of Richard D. James - aka, Aphex Twin - this type of completion anxiety was something he was hugely conscious of.

In an interview with French magazine, Les Inrockuptibles in 2001, Richard was asked about the making of his then-new record Drukqs, and how the process of making a more stylistically fluid and sonically-varied double album challenged his process.

“Only two titles are based on instinct, the other twenty-eight have been elaborated, refined, sometimes over two years,” Richard revealed. “The risk is that I never finish a piece: it is always at hand, ready to suffer the effects of my last fad [to] date. I want to push them [the tracks] further, to see how far they can be deformed without tearing” (this translation was assembled by user ‘rekosn’ on the WeAreTheMusicMakers forum).

Sometimes, as Richard indicates, that sense of constant refinement can be spurred by the same spirit of creativity and invention that your initial idea was birthed from. Therefore, it’s a tricky tightrope to walk - but if you want to ever get your music heard (and be confident in your work) you’re going to have to learn to strike that balance between creativity and productivity.

A simple rule to follow is to set a hard deadline for the track, album or project to be completed by. It might feel like you’re taking the fun out of a process that is supposed to be enjoyable, however imposing self-discipline can lock in a motivation to make decisions much faster - and commit to ideas as final.

Time pressure is what motivated the completion of Aphex Twin’s Drukqs - although not quite in the way you might think. Rather than demands from on high to finish a record by a certain date, the catalyst for James's speed came in the form of a heart-stopping blunder; he accidentally left his MP3 player on a plane.

That might not sound like too big a worry, but for James, it was potentially catastrophic.

This particular MP3 player contained around 300 of his work-in-progress tracks. Though Richard had all the masters, he was worried that - if found - these then-unreleased Aphex Twin tracks could appear online. “I lost my only wins, bread for ten years to come,” James shared in the same interview. “That's why Drukqs came out in haste. Panic-stricken, it forced me to listen to all my tapes, to sort them out.”

Though invigorated by worry aside from a self-prescribed deadline, James was able to finish the expansive double-album quickly. The fear of his work leaking overrode his natural tendency to compulsively re-mould, and often sit on his ideas for long periods.

Many of the tracks - including the utterly transcendental, Disklavier-generated Avril 14th - might never have seen the light of day if not for James’ forgetting to pick up that MP3 player.

Though James was hurried along by a sense of impending panic, the lesson we can learn here is that time-limitation can be a truly great motivator.

Beyond speeding up our workflows when actually working on our project, having a fixed target in mind can motivate us to spend more time in our studios, in our DAWs or with our instruments. Even on those evenings of afternoons where we’d rather do something a bit lazier (or head to the pub), wanting to get an album or project out by a certain point (or, in fact promising our audience to do so) can give us all the kick up the posterior we all sometimes need.

So, gather up those half-finished ideas, commit to a completion date, impose a fixed time-span on yourself and get to it. You might be surprised at how efficiently you work (and how imaginative you can be within a limited framework).

Whatever the outcome at the end - that’s what you live with, warts and all.

If you need more prescribed routes to get your tracks finished, we put together a pretty thorough, overarching guide here.

We’re not saying you necessarily have to work this way all the time, but if you’re sitting on mountains of unfinished project files, fragments of chord sequences or even the beginnings of good, whistle-able melodies, then start the clock.

Time is ticking.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

“How daring to have a long intro before he’s even singing. It’s like psychedelic Mozart”: With The Rose Of Laura Nyro, Elton John and Brandi Carlile are paying tribute to both a 'forgotten' songwriter and the lost art of the long song intro

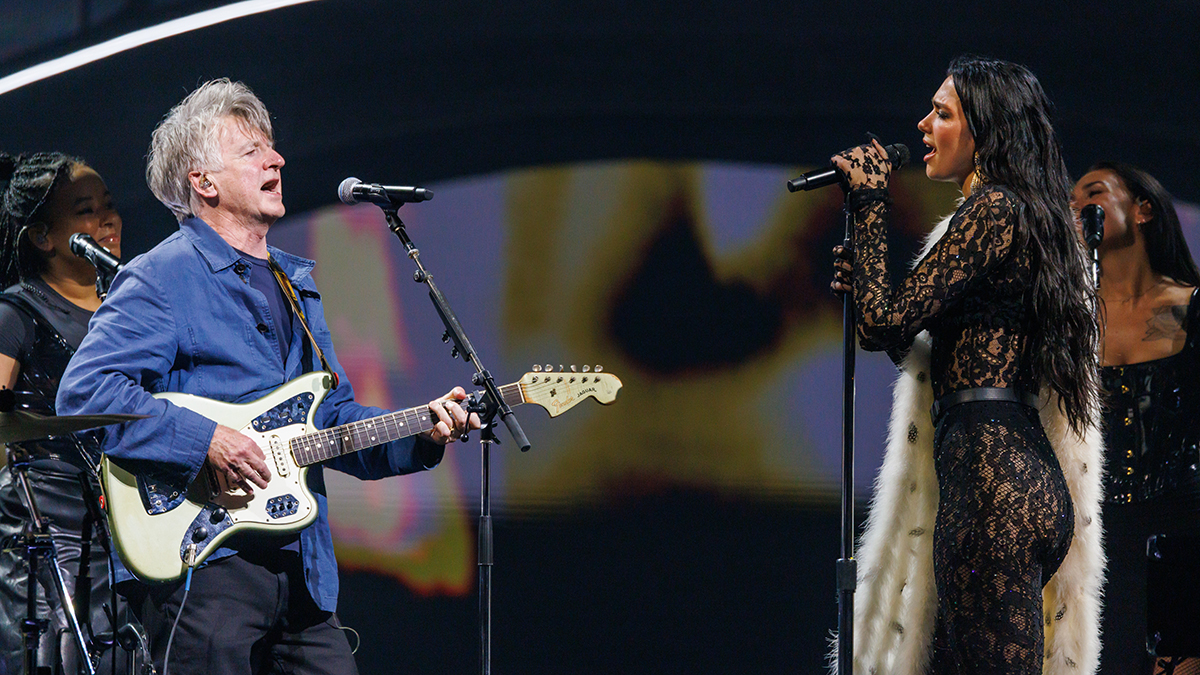

“Give it up for Neil Finn!”: Dua Lipa sings a Crowded House classic on her Radical Optimism tour - and brings out its writer to perform it with her