“The next time a musician says to you 'shall we try this a little more allegro?' you will know exactly what they mean”: The quick guide to the theory behind tempo and bpm

Never miss a beat again, with our quick guide to the theory of tempo and meter.

If you find yourself working with musicians, their style of instrument and musicianship will inform how you may interact with them on a musical level. So, improving your understanding of the vagaries of tempo will stand you in good stead when engaged in spontaneous collaboration.

As the culture of western music effectively transported itself from Italy, it's no surprise that many of the classical terms used to describe tempo and speed in music are descriptive in nature.

This means that knowing which term means what speed, becomes something of a memory test, made worse by the fact that there are a lot of terms - and they cover a very wide range.

The good news is, it's also very commonplace to use a numerical indicator of tempo, described in bpm (beats per minute).

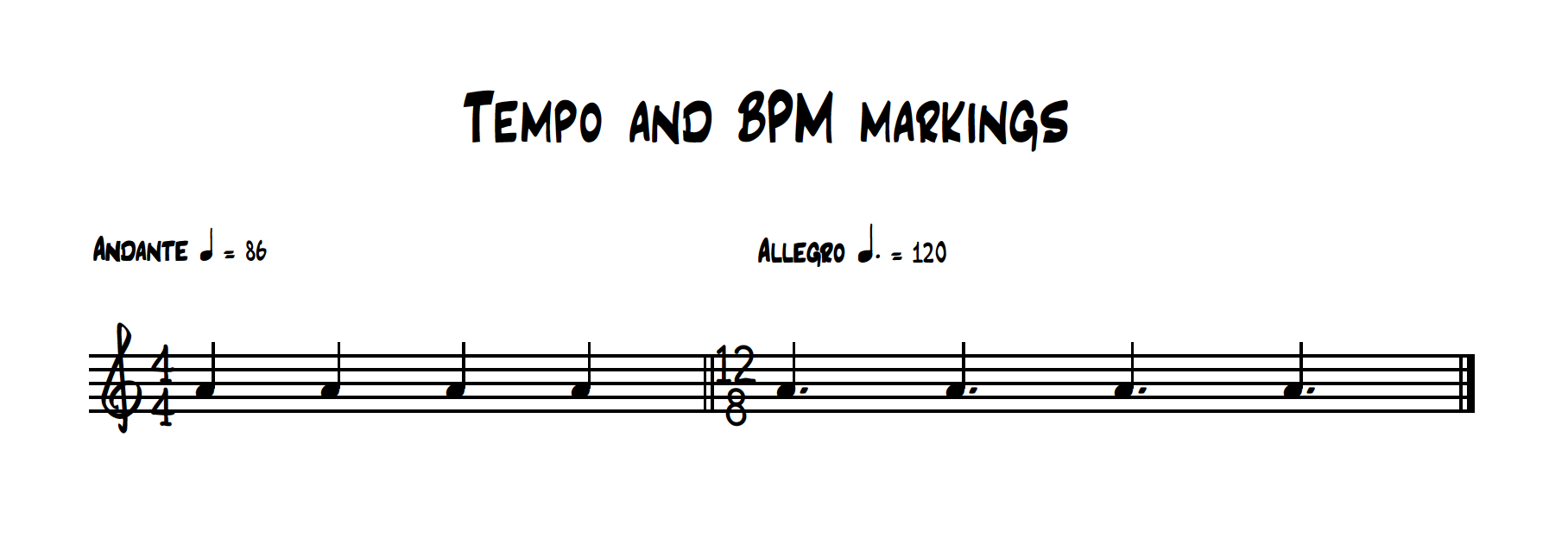

It's also exceptionally common for both to be used side-by-side, and there are only a few Italian tempo indicators that are used on a very regular basis.

A little allegretto!

One of the problems with using Italian terms is that the designated tempo assigned can be fairly broad, leaving it open to interpretation.

Here are six of the most common examples:

Lento - Slowly : 40-60bpm

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Adagio - Slow and stately : 65-75bpm

Andante - Walking pace : 70-100bpm

Moderato - Moderate pace : 106-120bpm

Allegro - Fast : 106-160bpm

Presto - Very fast : 160-200bpm

Metronomic culture

It’s thanks to composers such as Beethoven, who wanted to be more specific about their metronomic intentions, that gave rise to the use of the term ‘beats per minute’ (bpm).

Relating this to the current age, any DAW-based composer or producer will exclusively work with numbers and bpm rather than these old Italian terms.

As the description suggests, the numeric indication informs the musician of exactly how many beats there should be per minute. This can be exceptionally useful, particularly if you don't have a metronome to hand, but you do happen to have a wristwatch!

Providing your watch offers a second hand, it's clearly very easy to work out that a tempo of 60bpm translates to one beat every second. Double this to two beats per second, and you immediately conjure up 120bpm

This can also be useful in the instrumental practice domain, where you might want to adopt one of the Italian terms, but work at the lower end of the tempo bracket, increasing the tempo as you practice. This is a pretty common pursuit for any musician who practices regularly.

All about the unit

So far so good, but there is a slight sting in the tail, and it is all to do with the way music is written, and the unit you may describe as a ‘beat’.

Most commercial music adopts a four-square construction, using four beats to every bar, but sometimes the unit described as a beat may not be quite as it seems.

A case in point could be the time signature we describe as 12/8. As indicated, this signature employs 12 quavers or 1/8th notes per bar, but we tend to count it in four.

This means that for every beat we count, there are 3 quavers to each beat.

We could verbalise this counting pattern like this :-

"1-and-a, 2-and-a, 3-and-a, 4-and-a, 1-and-a…." and so on

There may well be a written intent relating to this 12/8 arrangement, at the beginning of a score.

Using a very basic mathematical and musical equation, there will always be an ‘equals’ sign in the middle, with a note value to the left, and a bpm numeric to the right. The note value on the left is the beat unit, while the bpm number on the right indicates how many of that note value-per-minute there should be.

So, the next time a musician says to you, 'shall we try this a little more allegro?’, you will know exactly what they mean.

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK