“Sometimes you don't want to be overtly happy or sad and a suspended chord strikes that perfect balance”: How to understand and use suspended chords effectively

Prepare to be suspended in disbelief, as we expand our triadic horizons with some suspenseful harmonic tricks.

Triads are incredibly useful for creating quick and easy harmonies, but altering the middle note of a triad can completely change your production’s character, and inject real interest into your harmonic narrative.

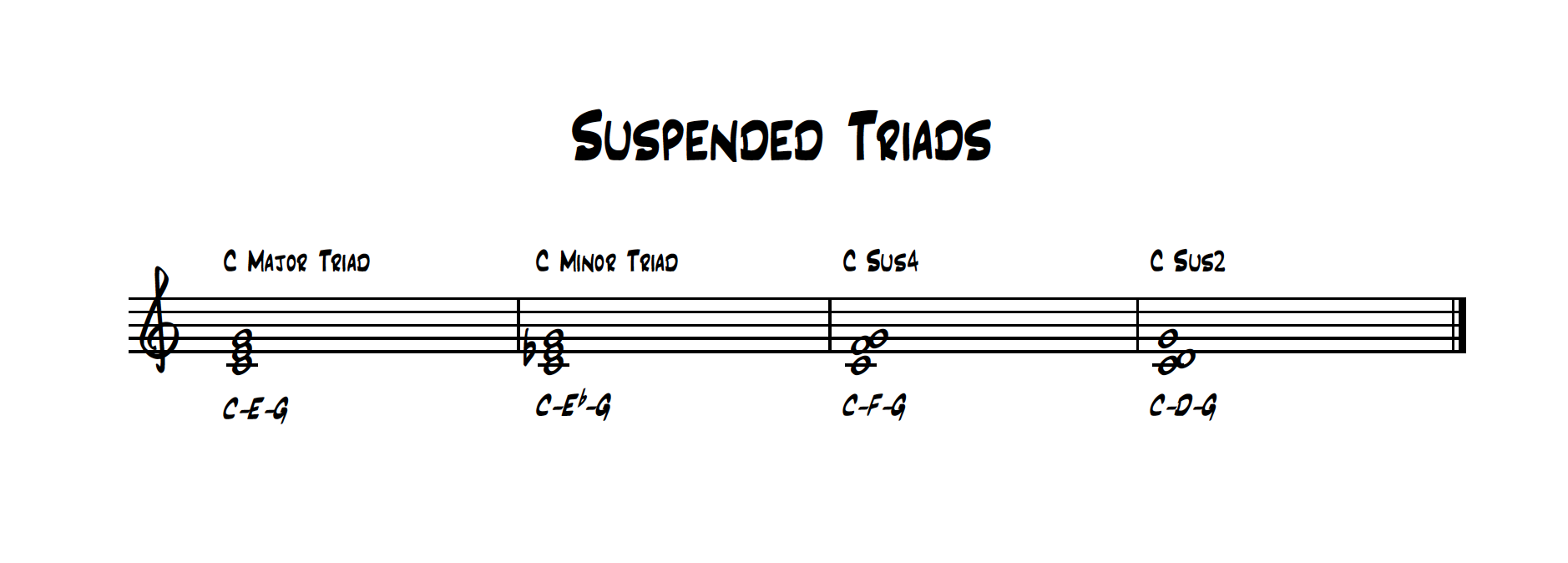

The one note in a triad that confirms whether we are in a major or a minor key, is the third. As the moniker suggests, the third of a triad is also the third degree of either a major or minor scale, and in a root position triad, resides in the middle of the triad/chord.

Sometimes, we might want to write a piece of music which is more nebulous in character, neither hinting at a major or a minor tonality. This is an effect that is exceptionally easy to achieve, merely by moving the third of the triad.

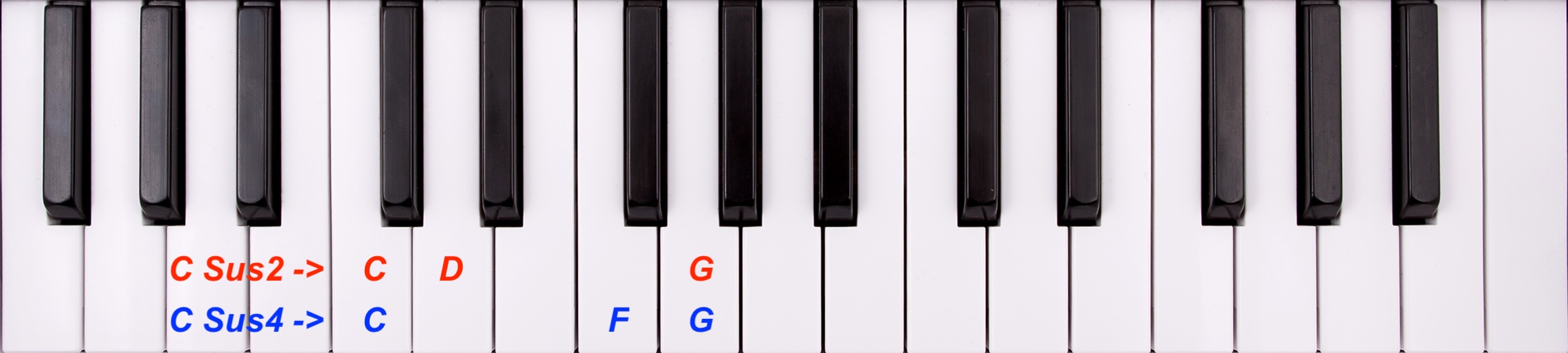

If we take the example of a C major triad, we’ll use the notes C, E and G. The E is the third of the chord, and the singular note that invokes the major tonality.

Raise this note to an F, and we create a triad which is often referred to as a 'sus4'. The ‘sus’ abbreviation refers to ‘suspended’, which is a hark-back to techniques drawn from harmony used in classical music.

However, the sus4 is exceptionally useful for building tension, when you don't want to suggest that you are in a major or a minor key.

You can also try dropping the E of your C major triad, to the note D instead. This creates another form of suspended chord, known as a sus2.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

As you may have worked out already, the number that we use while describing a sus4 or sus2, refers to the note that we have moved, and its position in a scale.

In the case of our sus4, the note F is the 4th degree of either C major or the minor scale, while D is the 2nd degree of our C scale, as used in a sus2.

In musical circles, musicians may just refer to a chord as a ‘sus’ chord; this always refers to a sus4 by default, so if you want a sus2, you’ll need to say so!

When to use a suspended chord

In its original classical incarnation, the suspended note of a sus4 chord, would often resolve to the third of the triad, an adoption that has been been around for literally hundreds of years.

Bringing us more up to date, there have been some very obvious placements of the suspended chord in commercial and pop music, across all ages and genre.

A classic example of a sus4 chord, resolving to a major chord, placed in a rhythmic cycle, would be the opening two chords to the classic track Pinball Wizard by The Who. The acoustic, rhythm guitar riff alternates between the two chords through the entire introduction, extending into the initial part of the 1st verse of the song.

The suspended chord is also a favourite of far more contemporary artists, such as Jon Hopkins. Much of his piano playing features the use of suspended chords, which in turn draws influence from film composers, such as Thomas Newman - another huge user of the sus!

What we really enjoy about suspended chords is their slightly ambiguous nature. Sometimes you don't want to be overtly happy or sad, by using a major or a minor key, and the use of a suspended chord strikes that perfect balance between the two, without ever giving the game away. Give it a try and add some jeopardy to your harmonies!

Read the previous instalments in our ongoing theory series below

- The pillars of music theory made simple

- How to become a master of melodies

- A quick guide to reading music

- How to understand rhythm when reading music

- Understanding scale theory

- How to use triads

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK