“Can you guess how small a 'hemidemisemiquaver' is?”: How to understand rhythm when reading music

Establishing rhythm in your sheet music is just as important as dictating pitch. We show you how to take and note your music’s pulse.

When you learn to read music, it’s much like learning to read a book. While the notes on the stave go up and down to indicate pitch, we also read from left to right, and that’s the element which relates to rhythm.

When writing notes on a stave, we are able to use a number of different note values to indicate our rhythmic preferences. This is essential for all instrumentation, from orchestral, keyboards and rhythmic guitar parts, through to percussion and drums.

If these notes were written as an endless stream of consciousness, it would be very difficult to read them, so to aid the reading process, we dice up the notes in to manageable portions, of a certain number of beats at a time. We describe these portions as 'bars'.

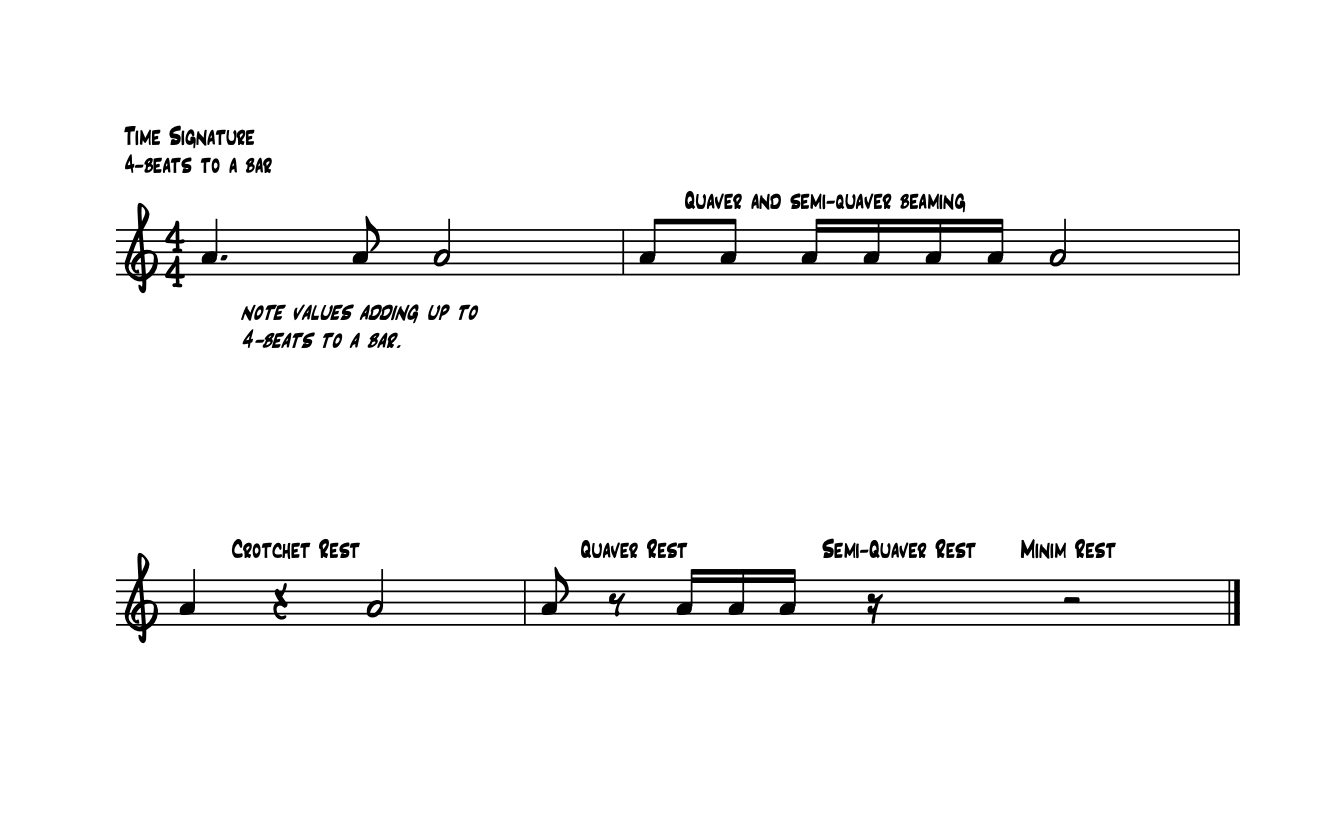

It’s common to have 4 beats to a bar, but you can literally have any number of beats to a bar that you like! However, pop culture has taught us that 99% of all songs utilise 4 beats to a bar.

The bars themselves are indicated by vertical lines drawn across the stave. These bar lines indicate where the bars start and end, while reflecting the 'time signature', which you will see at the beginning of the very first stave. The upper digit instructs the number of beats to the bar.

Crotchets and quavers

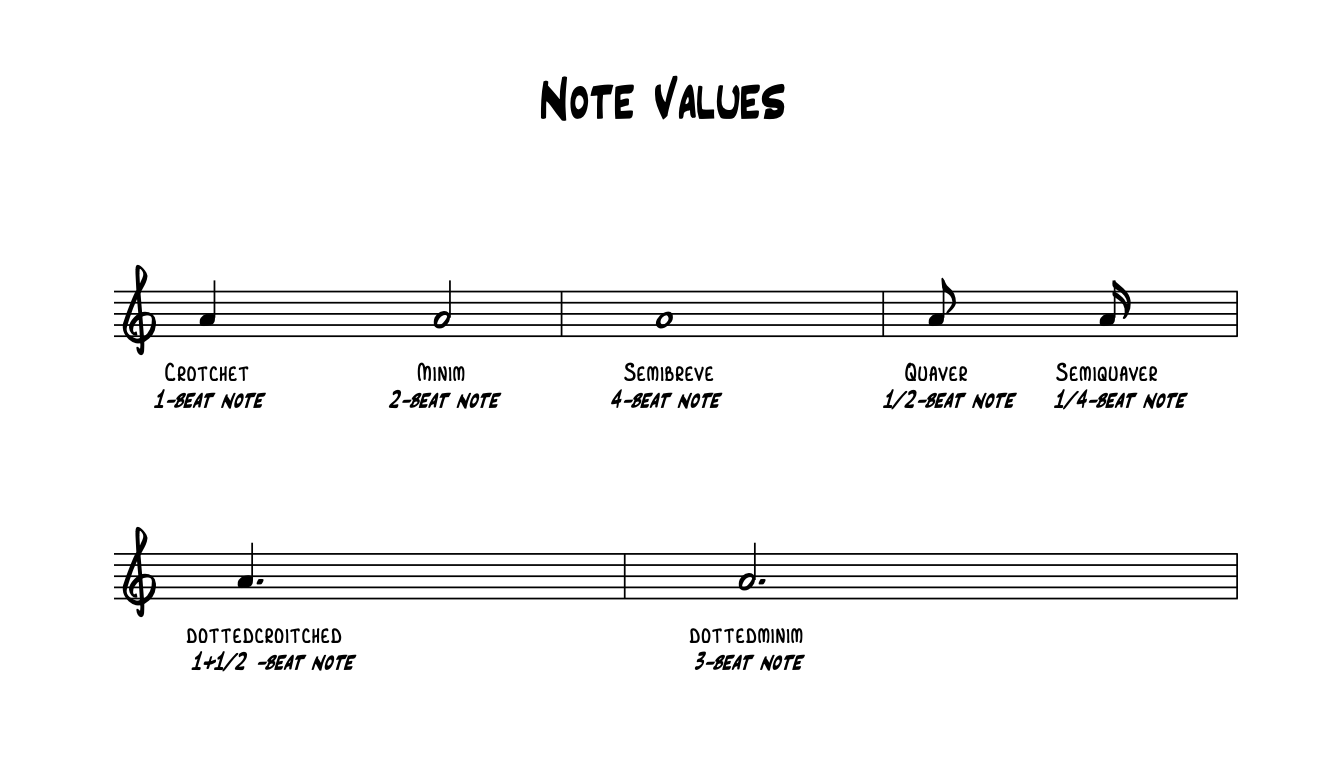

In European circles, different note values have names; a 1-beat note is known as a 'crotchet', 2-beat note is a 'minim', and a 4-beat note is a 'semi-breve'.

You can also use 1/2-beat notes, which are known as 'quavers', and 1/4-beat notes, which are known as 'semi-quavers'. You can go even smaller than that - can you guess how small a 'hemidemisemiquaver' is? Yep, very small indeed!

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Each of these notes is drawn on the stave in a certain way; crotchets use a black note-head with a stem, whereas minims are circular and hollow, also with a stem. Semi-breves don’t have stems at all, but are also hollow!

Quavers and semi-quavers look much like crotchets, but they also employ tails. A single tail, attached to the stem, indicates a quaver while a double-tail indicates a semi-quaver.

Bars and rhythms

When writing out rhythms on a stave, similar note values (such as quavers and semi-quaver) can be grouped together to make them easier to read. This is often known as ‘beaming’, using a beam to join the notes at the end of their stems.

You do have to think about the mathematics though, as each bar needs to add up to the value indicated by the time signature. If you’re working to 4-beats to a bar, just make sure your bars do not exceed this maximum, or rhythmic carnage might ensue! Also note that you can only beam quavers or smaller, and not crotchets and minims.

The importance of rests

Sometimes you may want to indicate that you don’t want a note played. Much like adding notes of a certain value, you can also add ‘rests’ to indicate that you don’t want anything to be played. Rests use the exact same note values, but they are written differently, as you can see in our example above.

You may have also encountered names for note values that refer to fractions. This principal is exactly the same, but instead of crotchets and quavers, uses descriptions of 1/4 notes and 1/8th notes. This system is often referred to as the 'American' system; think of the semi-breve as a whole note, and all the other notes are simply fractions or divisions. Hence a minim is a half note, crotchet a quarter note, and so on.

It may also be useful to know that in the US, bars are referred to as ‘measures’! It’s the musical equivalent of Imperial verses Metric, but thankfully you won’t need to grab your tape measure just yet!

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK