“A well-crafted sequence is successful wherever you may wish to use it”: Use these tried and tested chord progressions to build an engaging song

Creating the perfect harmonic or chord progression for your song or production is not easy, but we can at least draw some top-tips from the past-masters.

The presence of a well-crafted and performed chord progression can often be the glue that gels the song together. If executed well, it should support your melody and lyric, while grabbing listeners on an emotional level.

Before we dig into harmony too deeply, we must address a musical elephant in the room; chord progressions are arguably more essential for songwriters, than they might be for artists or producers working in some styles of electronically generated music or production.

Many of the most successful house/dance/EDM tracks don’t employ a significant sequence of chords. This is nothing new! It’s a concept that harks back hundreds of years to the chanting of plainsong. It was also made fashionable in the 60s, though a form of music known as 'minimalism'.

A lot of the electronically-produced music that we hear today could be regarded as fairly static in harmonic construction, relying on builds through rhythm and texture to generate structure.

Having said that, there is no doubt that any form of harmonic progression can offer something to just about all musical styles, so it’s worth considering, regardless of your chosen genre.

To get us underway, we’re going to concentrate on the construction of a verse or chorus’s harmonic structure; the two are interchangeable, depending on the way you want to use them, and in some instances, can actually be the same!

The chances are, you’ll be sitting with a guitar or keyboard in front of you, and playing a few chords to get you going, so start by choosing a key.

The most important decision at this stage could be whether you want to work in a major or minor key, depending on the outlook you want to portray.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Major keys will sound happier and brighter than minor keys, but that’s no use if you’re writing about the fact that you’ve just been jilted! Although, there are examples of reverse psychology. Think of CeeLo Green and Forget You, which is very major in key, but all about his ‘ex’ dumping him!

We’re sticking with C major - a nice keyboard key!

Old favourites

When creating a harmonic progression, particularly for a song, we are looking to create a sequence of chords which may repeat as the song progresses. The harmony is fundamental in setting the song’s tone and feel.

Part of the process involves crafting a balance in the structure that’s pleasing to the listener, as well as feeling nice to play or sing along with.

We can learn a lot from existing material, so let’s start by examining one of the most used and longest established chord sequences in existence.

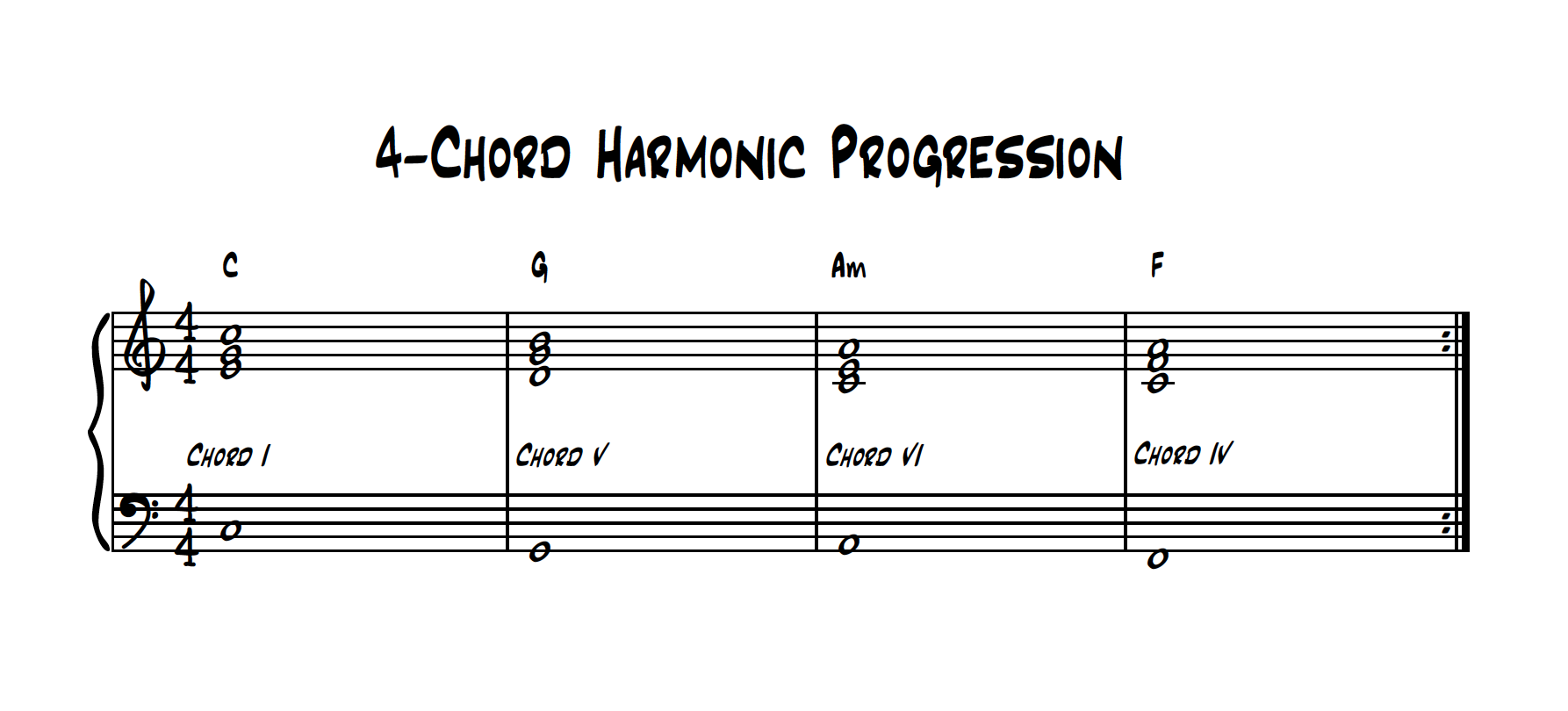

Try the following, played as a chord per bar:

C major - G major - A minor - F major

This can also be described as the following chords:

I - V - VI - IV (or 1 - 5 - 6 - 4)

If you play this sequence through, it probably sounds overwhelmingly familiar. That's because it has been used by everyone, from The Beatles, U2, James Blunt, Black Eyed Peas, Spice Girls, A-ha, Beyoncé, Miley Cyrus, Blink 182… you get the picture!

It’s important to note that, as demonstrated by this selection of artists, this sequence crosses all genre and musical boundaries, proving the point that a well-crafted sequence is successful wherever you may wish to use it.

Let’s unpick why this harmonic sequence works so well. When working in a major key, chords or triads are based upon different degrees of the scale, reflecting a major or minor tonality at the individual chord level.

Chords I, IV & V are all major, whereas chords II, III and VI are minor. Chord VII is diminished, so we don’t tend to us it very often, particularly as the notes are not that dissimilar to chord V, which we tend to use instead.

This successful sequence of chords is overtly major, with a singular minor chord thrown in (VI) to create a sense of contrast and balance. The last chord in the sequence is also major, and leads nicely back to chord I.

Note that the chord of A minor (VI) is the 3rd chord of the sequence, which is a strong bar, subservient only to the 1st bar.

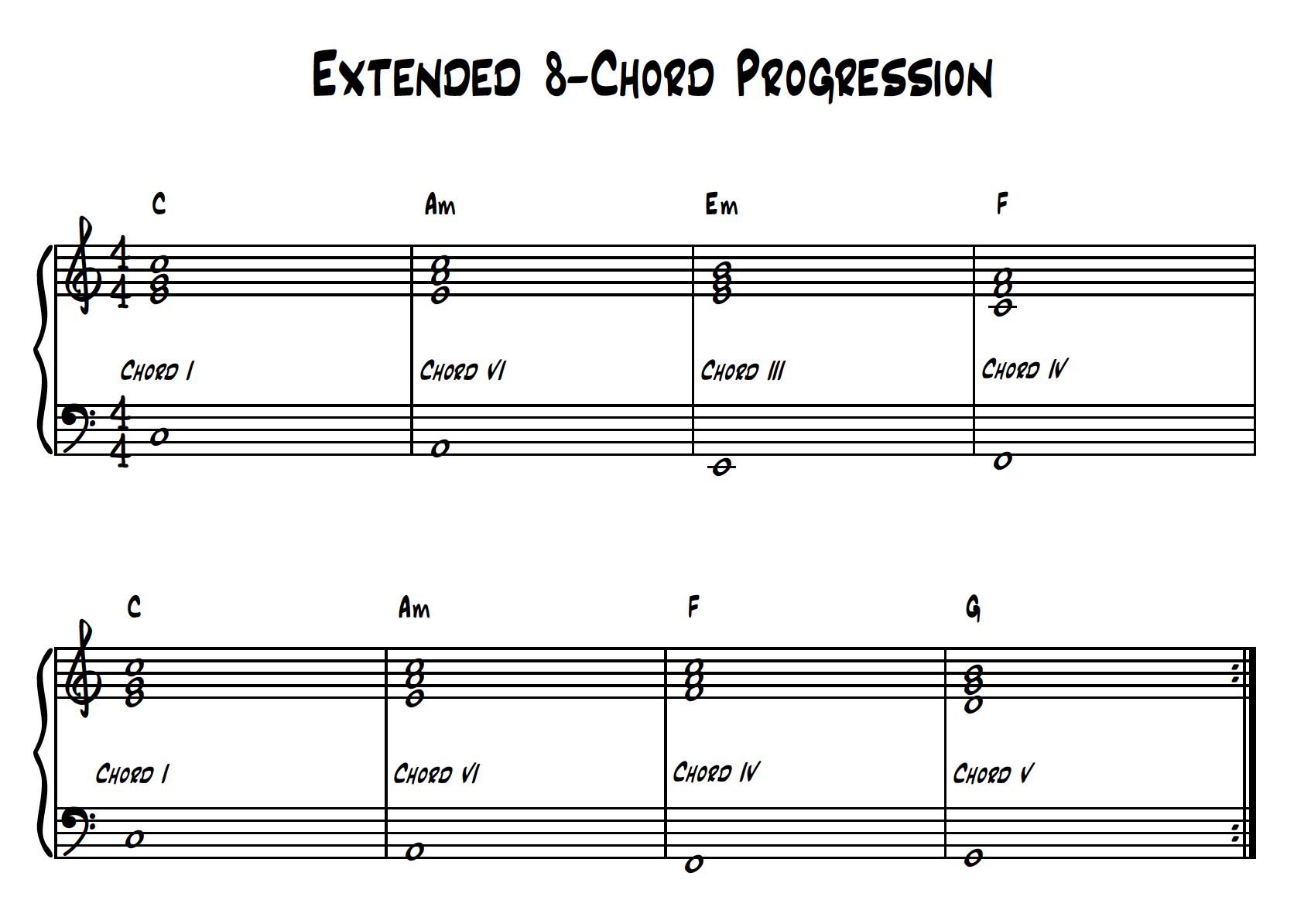

If we re-order these same chords, we can hear another popular sequence:

C major - A minor - F major - G major

I - VI - IV - V

This also sounds very familiar, but we could play around further and change the third chord to D minor. This will place a minor chord on the 3rd bar, creating equal weighting, as we now have two major and two minor chords.

Ultimately, we are looking to take our existing structure but swap chords to create a more desirable or different effect. This process could ultimately mean that we create an 8-bar sequence, which might look something like this:

C major - A minor - E minor - F major

C major - A minor - F major - G major

Dominant chords and the chorus

One chord which we have to take a moment to examine, is chord V, which we also describe as the 'dominant' chord. In our key of C major, this is a chord of G major.

Dominant chords are really useful, as they create a perfect pivot for heading back to our home chord of C major, but they also have another exceptionally useful trick up their sleeve; they are excellent for building tension.

If we consider our eight bar structure, which finishes with a chord of G major, we could extend that chord by a couple of bars or more, and use it as a device for leading into a new section, such as a chorus. The buildup will be perfect, as the accompanying sense of anticipation is in place, before we move back to our chord of C major.

By the nature of the song-shaped-beast, you will probably want to save your best or catchiest chord progression, hook or melody for your chorus, but there is nothing to stop you using the same chords, or better still, play around by swapping-out chords for alternatives, or ‘substitutions’ as they are referred to.

One important point to be aware of though, is that harmonic content is not an element of a song that can be copyrighted. There are only so many chords, and they can only be reordered so many times, which also explains why so many songs share the same harmonic characteristics.

There have however been many examples of songs being sued, where the similarity extends beyond the harmony, so be sure to mix things up so that you’re not trampling on another well-known tune. You wouldn’t want to end up on court, fighting over four chords would you?

Read the previous instalments in our ongoing theory series below

- The pillars of music theory made simple

- How to become a master of melodies

- A quick guide to reading music

- How to understand rhythm when reading music

- Understanding scale theory

- How to use triads

- How to use suspended chords

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK