“At certain points in music history it became fashionable to place accents on certain beats”: How to score a drum part

Understanding how a drum kit works will unlock the secrets of drum programming. We dive into kicks, snares, hats and drum scoring

Drums are often unfairly considered to be the poor cousin of the band. Cue the joke, ‘what do you call a person who hangs around with musicians? A drummer!’

But drummers have had the last laugh for quite a number of years. With the advent of drum machines and electronic kits, many sensible beatmakers, took to programming the machines and loops themselves. Why? Because they were the people that understood how patterns and grooves really worked, and that's long before we get into the topic of drum fills.

For 99.9% of all commercial music, the drums represent the core engine of a track. It's the element that drives the song along, and also the element that all musicians will listen to, in order to lock in to a groove.

Think about this logically; it’s the drummer that’s dictating the feel, and everyone else should listen and take note!

It's also important to stress that this sense of compliance is just as important at the DAW level, as it is for live work, but for producers and composers, having a basic understanding of how a drum kit actually works is invaluable to creating better drum parts and grooves.

The core components

Drum kits come in various shapes and sizes, and if we widen this to the world of production, we have many different colours and timbre-ranges for each instrument, along with a considerable number of elements which could be considered percussion instruments.

For our purposes, we’re going to keep things basic, distilling the drum kit down to 3 of its main components; the bass drum, the snare drum, and the hi-hat.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The bass drum (aka the kick) is the large drum which sits on the floor, and is played using a beater, connected to a pedal (usually played with the drummers' right-foot).

The snare drum consists of two drum skins above and below the drum (aka heads), with a set of springs (snares) which are stretched across the bottom drum head, creating that bright ‘rattly’ sound.

These two drums are thought to represent one of the most basic humanistic elements, used to create the rhythm of life! In this context, the kick represents the stamping of feet, while the snare reflects the clapping of hands.

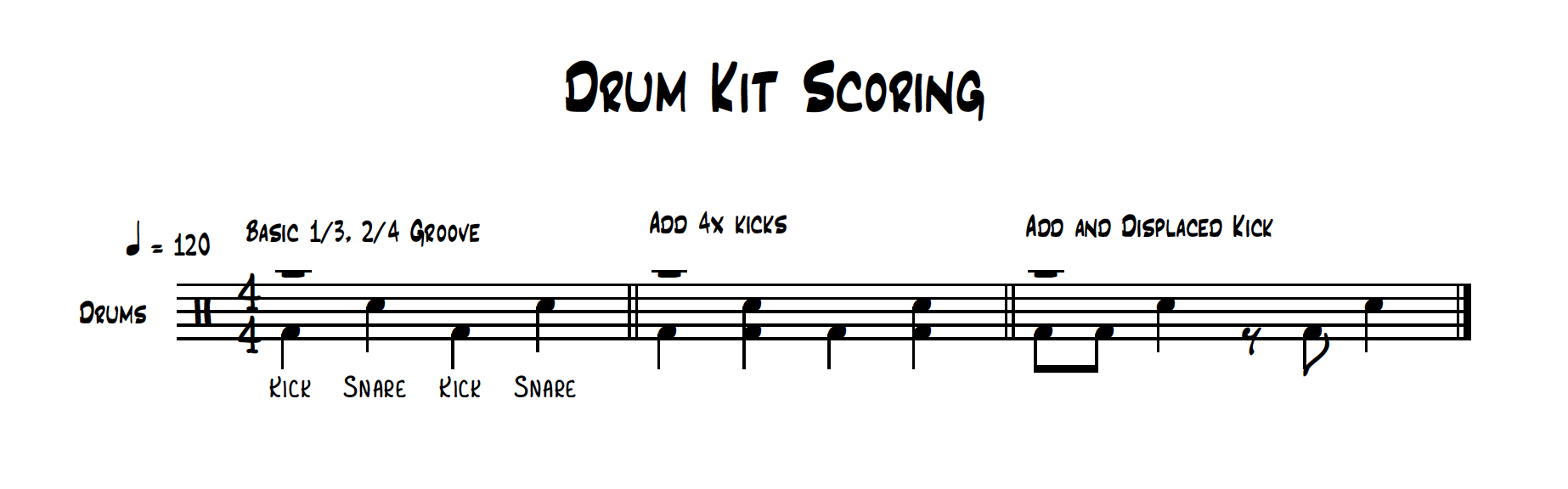

If we bring this up-to-date and place it within the construct of a traditional musical bar of music, we end up with a kick drum on beats 1 & 3, and a snare drum on beats 2 & 4.

Conveying this to a drummer, notes are presented in notation form, through a specific form of drum notation.

Each line and space on a drum score stave, corresponds to a particular drum or drum kit element. Furthermore, drum kit notation uses a mixture of conventional and alternative note-heads.

The kick is written on the bottom space of a drum clef, while the snare drum is notated on the third space up. Importantly, the stems for these notes should go in a downward direction, while also using a conventional note head.

This basic construct is the absolute cornerstone of the vast majority of drum patterns. There are almost too many derivatives to cover in one article, but these can vary from adding further beats and accents, to displacing beats.

Even so, the drums will always be the element that sets up the basic feel and groove of your track, stemming from the kick and snare, in the first instance.

One easy and identifiable derivative of this basic pattern is to add the kick on all four beats of a bar. We could also add additional kick beats, or displace where the kick plays, as you can see in our example.

The third important element of the drum kit, subdivides the kick and snare patterns.

A physical hi-hat is made up of two cymbal-like components, that close together to form a unit. In this closed state, they produce a high and bright sound which is both percussive and relatively short.

Thanks to the use of a pedal system, which is normally operated by the drummers left foot, the two cymbals can be opened slightly, to create a sizzling sound, which is longer and more sustained. These two variations of sound are predictably described as closed and open hi-hat.

In its closed state, the hi-hat can provide a sense of drive and impetus, as it generally tends to play faster rhythms, sitting on top of the kick and snare patterns.

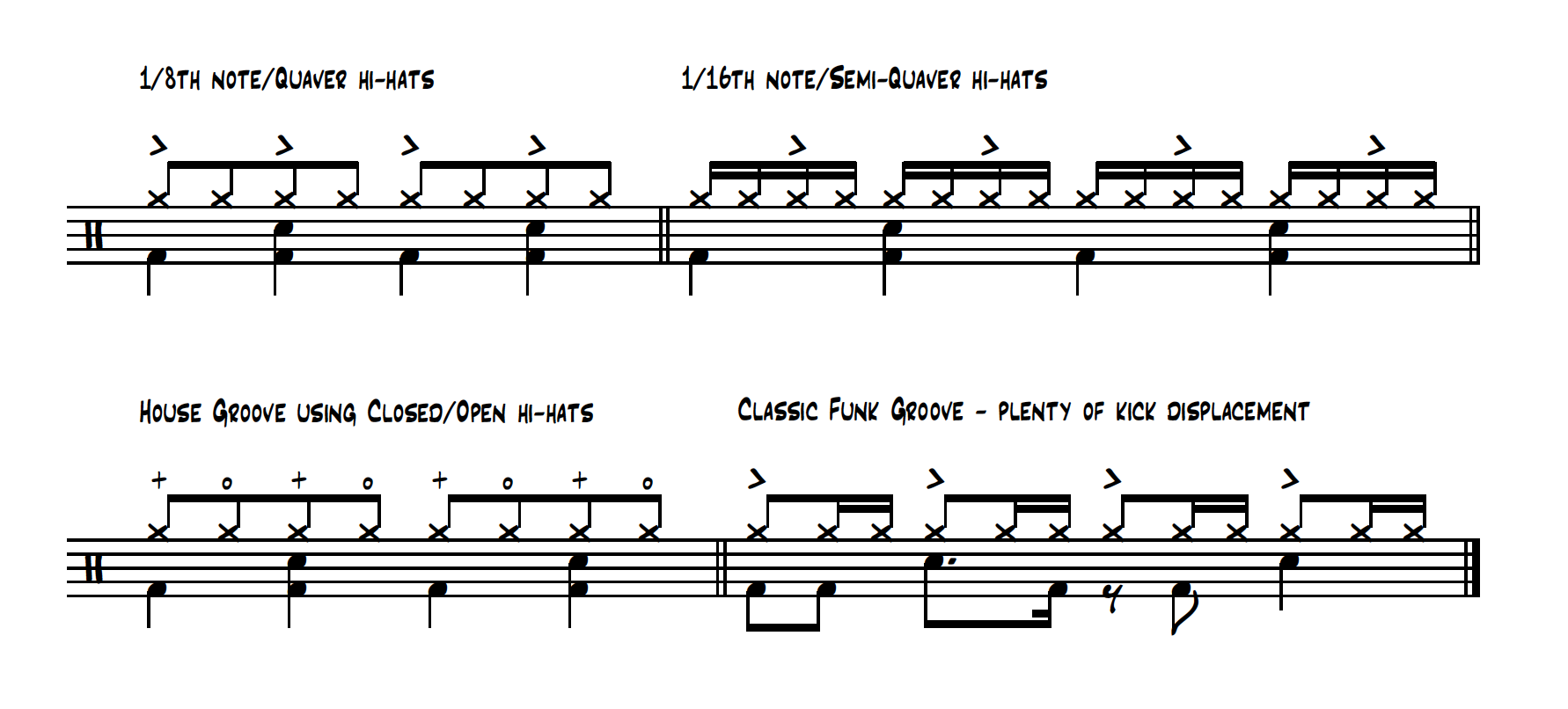

Interestingly, the type of pattern and speed, is often dictated by the style of music.

Similarly, certain styles of music rely heavily on the open hi-hat; it became very popular in the seventies to use an open hi-hat on the off-beats of a drum pattern, for disco and dance-based tracks. This influenced the dance culture of the 90s, and is still a drum staple today.

Switching the hi-hat part from an 1/8th-note pattern to a 1/16th-note pattern, will create quite a different feeling.

At certain points in musical history, it has become fashionable to place accents on certain beats, such as an accent on every third 16th-note, in the late 80s, or the classic funk grooves of the 70s and 90s. (In fact, many of the 70s grooves infiltrated the 90s by way of being sampled!)

Dictating your requirements for a hi-hat on a drum score is not complex, but it is important to be exacting.

Firstly, the hi-hat adopts a position which is just above the top line of the drum stave. In much the same way that the kick and snare note head stems go in a downward direction, the hi-hat stems must go in an upward direction.

This keeps the stems out of the way of each other, making it easier to read. However, it is also vital that when writing a hi-hat part, you use a ‘X’ as a note head.

This instructs the drummer to play the hi-hat, whereas using a conventional note head would indicate playing a tom instead.

By default, it will be taken as read that you want a closed hi-hat, but you can indicate your preference through the addition of ‘+’ and ‘o’ icons, above the note heads themselves.

The ‘+’ sign tells the drummer to play a closed hi-hat, whereas the ‘o’ indicates open, unsurprisingly!

One of the reasons that drummers became so involved in programming drum machines is because they understand the instrument, and it is a pretty safe bet that as they only deal in rhythmic matters, they will be far better placed to advise and help create a worthy groove.

This also extends to drum fills, which are the exciting bit you tend to hear at the end of every 8 or 16 bars, before you head into the next section of your song.

For this reason, it's become commonplace to provide a drummer with a basic score and concept of your requirements, before writing ‘slashes’ on your drum score, which indicates that the drummer should just get on and repeat your idea.

But when it comes the drum fills, just write the word ‘Fill’ above the drum score, where you would like your fill to be placed. In terms of fills, lose the shackles of the score and let your drummer have a little fun before returning to the fixed beat.

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK

“I’m sorry I ruined your song!”: Mike Portnoy hears Taylor Swift's Shake It Off for the first time and plays along... with surprising results

“Nile's riff on Get Lucky is a classic example of a funk riff, where the second of each 16th-note duplet is slightly delayed”: Locking down the theory of groove