Sampling tips for beginners

An introduction to the world of the sampler

Samplers can be tricky when you first boot them up. Aside from getting sound into the damned things, you've then got a plethora of options to get it out again. Here are a few creative solutions to get you past the head-scratching stage.

What you'll need

First of all, you're going to need some sample material. Pretty much anything will do, although ideally try to find something rhythmic - these tricks work best if they're matched to tempo. We're assuming your sampler is either a software model or a hardware one attached to a sequencer.

Audio - Main loop

This is the loop we'll be sampling throughout this tutorial.

1. Sample trigger

Once you've got a loop sampled, you can have fun triggering it by sequencing a little phrase for it. To begin with, play in a phrase based on the keynote. The keynote is the note on which the original sample plays back at its original speed and pitch. If you know the tempo of the loop itself, it's easy to generate a musical phrase, complete with little stop-start moments.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The phrase we've prepared here does exactly this, never playing for more

than a few beats without being retriggered. If the retriggers are close together they'll sound like a little drum roll. Otherwise, the effect will be a kind of 'stuck-record' sound.

You don't have to do this for a whole musical phrase either - performing these types of retriggers on drums alone is a great way to get away from simply triggering a pre-existing drum loop. It's also a great trick to use if you're a Dance producer who wants to hint at a vocal part before it appears in its entirety.

Audio - Sample trigger

Having sampled our loop, we've triggered it at different points to create a new pattern.

2. Section loop

Looping is a one of the most common sample techniques and allows you to set points around a chosen bit of audio, which will then play round and round - hence its name. You can set any loop length you like and for the previous example it would make sense to loop a one, two or four-bar phrase but equally, it's great to find a short section and loop just that bit.

In this example, we've let the whole phrase play as before. However, we've also set our phrase up on three other keys, and for these we've set loop points round just a tiny bit of audio.

The result is that when these keys are triggered, rather than hearing a bit of the phrase, the audio becomes a strange buzz - less like a stuck record and more like a damaged CD.

As our phrase plays though, we've interspersed it with these little loop fragments, which gives it a glitchier feel. This is a technique that's favoured by Fatboy Slim and Squarepusher. You can here an example below.

Audio - Loop bits

You can choose your extracts from anywhere, and don't be afraid to experiment with different loop lengths - even the tiniest of changes will make a lot of difference.

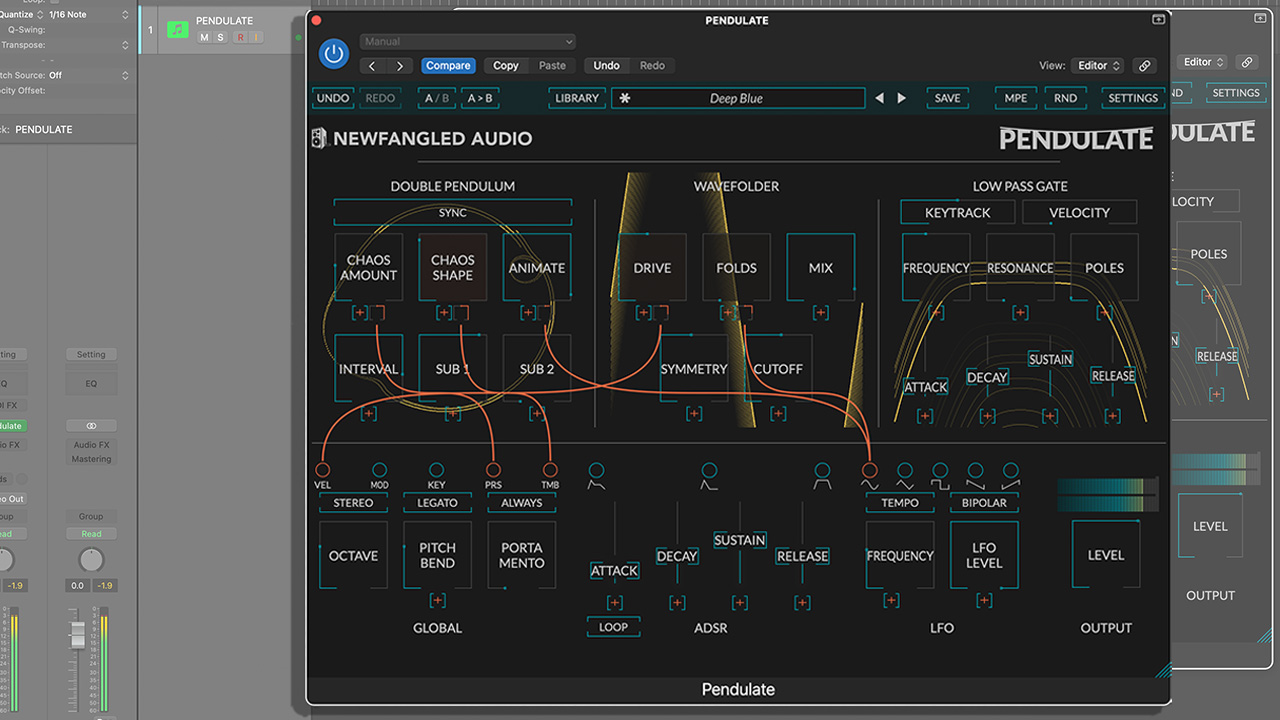

3. Filtering

The filter section of a synth is responsible for its tone, or timbre. Filters set a cutoff point, above or below which frequencies are cut. In other words, you can reduce the volume of either the bright or dull bits of a sound, leaving the rest present.

Which parts of the sound remain and which are lost is dependent on the type of filter you use - low-pass filters leave bass while reducing the volume of treble, whilst high-pass filters do the opposite. In this example we've filtered our loop using a low-pass filter. You can hear that as the tone of the sound changes, the bass always remains present; it's just a question of how much treble is present at any time.

Alongside the cutoff control is resonance, whose job it is to boost frequencies at the cutoff point. If the cutoff frequency is towards the top you'll notice the treble is sharp and super-crisp, whereas if the cutoff point is at the bottom end the bass gets a lot warmer and boomier.

Audio - Filtering

In this audio sample we've adjusted the cutoff and resonance so that the tone goes from bright to dull and back again.

4. LFO part one

LFO stands for 'Low Frequency Oscillator'. LFOs are designed to produce a background waveform, which can be 'channelled' into the other parts of a synth or sampler.

Broadly speaking, the oscillator section of a sound is for pitch, the filter section for tone and the amplifier for volume. So if you point an LFO at the filter cutoff control, this dial will effectively rise and fall, driven by the LFO's waveform.

This is exactly what we've done in this DVD example, and you can hear the effect after the first four, LFO-free bars. For the second half of the clip, the LFO comes in and the tone-quality changes - now the brightness rises and falls in time with the loop.

Audio - LFO part one

One of the big advantages of software samplers is that it's easy to synchronise LFOs to the tempo of your piece, so that changes like this can happen 'in time' with your loop.

5. LFO part two

Depending on the complexity of your sampler, you may find it has more than one LFO. This means that you can repeat the above process, selecting a different 'target' for your second LFO to that of your first. For example, you can independently influence the filter cutoff and the volume simultaneously. Selecting different LFO speeds means you could have volume rise and fall over a bar (for instance) while the cutoff point rises and falls every half a bar.

Audio - LFO part two

On the example above we've kept our filter changes from the first example, but assigned our second LFO to control pan, so the loop now wobbles beautifully back and forth between the speakers. Alternatively, you can set completely free, non-synchronised rates. It's also possible to change the shape of the LFO's waveform; rather than the smooth up and down ramps you can use more unusual shapes or even totally random ones.

6. Half-speed, double-speed

This is an extension of the first sample trigger example. Instead of triggering just the keynote, you experiment with notes played an octave below the keynote and an octave above. What you'll soon discover is that the octave below produces a half-speed loop, whereas the octave above performs it at double-speed.

If your sampler is connected to a sequencer, this means that composing slightly more interesting rhythmical phrases is simple and this is what we've done on the sample below.

Audio - Half-speed, double-speed

Starting with a half-speed loop, we've layered this with a normal speed loop after four bars and then interspersed this with bursts of double-speed in the last bars.

Play around with the notes between the octaves too, but these won't synchronise to tempo in such a straightforward way. Triggering quick notes on these intermediate keys produces a 'tuned loop' effect. Several early Aphex Twin records do this, with a whole tracks sampled and triggered at different pitches to create one-shot effects.

7. Pitchbend varispeed

Most samplers will allow you to set a pitchbend range, just like synthesizers. As we've just seen, triggering samples at lower pitches means they play back at lower speeds, so what better way to introduce varispeed to your sampled loop than playing or drawing pitchbend changes over the sequenced part you've written?

You can create anything from records speeding up and slowing down to retro, multitrack tape effects. You should also think about the average speed of your loop - any time the pitchbend data is below 0, the track is slower than its original speed and will therefore finish late, while any data above 0 will finish too soon.

A fun thing to do is to drop the data down and then up so the loop finishes on time but having been dragged in both directions en route, although this takes a bit of trial and error. We've done this on the example below.

Audio - Pitchbend varispeed

8. Sidechain one

If you're using a software sampler then this one's for you, although it's a bit more complicated. Most sequencing programs allow you to set up sidechains into plug-ins and instruments and there's a good chance that your sampler will have a sidechain input. Think of sidechains as ways of routing signals from one place to another, but rather than having to leave your computer to do so, they can operate internally.

In this context, we can route a signal into the sampler via a sidechain then choose which of the sampler's functions the sidechain will control - in much the same way as we did before with LFOs.

In the example below we've set up a short, hard percussion sound, which we've recorded to a spare audio track. We've then told our sampler's sidechain panel to 'look' at that audio track, and thus it becomes the trigger. We've then set the cutoff point as the sidechain's target and sure enough, on pressing play you can hear the tone of the sound changing, which is the sidechain at work. As we don't want to hear the sidechain sound itself, we've turned off the audio track's output.

Audio - Sidechain one

9. Sidechain two

This second example is more complicated again. We've used the same sidechain but rather than restricting the target to the cutoff point only, we've gone nuts with targets. In total, we've asked the sidechain to affect cutoff, resonance, pan, volume and pitch - if you listen carefully you should be able to hear all of these.

It's at this point that you realise that your choice of sidechain sound becomes crucial. Here we've gone with a short, sharp sound, and consequently each hit triggers a short burst of activity before the sampler settings 'recover' to their default position until the next sidechain hit. You can particularly hear this on the pitch information, with a short audible 'wobble' present every time the sidechain plays.

Forget looped phrases for a moment - imagine sampling a long texture or even the sound of the wind and then applying this type of sidechain modulation. Very soon you'll be sound designing with the best of them. Depending on which sampler you're using, setting sidechains up might be very easy - or more complicated. Even if these two examples seem confusing initially, do persevere as the results can be impressive.

Audio - Sidechain two

10. Reversing

Reversing is the kind of trick that samplers do brilliantly. Reversing remains popular because it sounds weird and wonderful, although too much of it can certainly take it beyond being a good thing, as our first example shows.

Audio - Reversing

This is just a straight reverse and to be honest, it's not that great. In the second half though, we've decided to treat the reversed loop as a kind of intro, so we've put it through a high-pass filter, added some resonance and slowly teased the cutoff frequency up and down, so that the loop cuts through in some places and becomes closer to a thin, more raspy noise in others.

11. Reversing and Slicing

Combining techniques often yields some pretty creative results. Reversing and re-sampling both concern sample playback alone and therefore are excellent bedfellows.

Audio - Reversing and slicing

In this example, we've set up the same loop on a number of keys, but selected various bits and reversed them whilst chopping the original loop into a number of sections so we can trigger more than just the first bit of the loop. It's a more liquid, unpredictable phrase, which still manages to retain the characteristics of the original loop.

Try this as an exercise: record a two-bar phrase and, armed only with your sampler, turn it into a full track via as many sample processes as you can.

12. Envelopes

Envelopes allow you to shape sound over time, meaning that across at least four separate stages a part of the sound can evolve or change. The best way to understand this is an envelope that relates to volume.

Envelopes let you control four stages of time - Attack, Decay, Sustain and Release. When applied to volume, the attack time sets how long it takes for the sound to 'fade in', with settings near 0 providing immediate attack and longer times stretching up to a few seconds.

Release does the opposite - it controls how long a sound takes to die away once a note is released. Sustain sets the level for the sound once it has passed through the attack and decay stages, and the decay itself sets a length of time for the sound to fade away (after the attack phase), assuming sustain isn't set to maximum.

Audio - Envelopes

In this example, we've set up a filter envelope and an amplification one. It's important to remember that filters are all about tone, so you can hear the loop get brighter when it first triggers and then later you can hear it die away again when the note is released. The amplifier envelope is set to allow these changes to be audible.