Raise your 12-bars

ELECTRIC GUITAR WEEK: When playing your way through a 12-bar blues, it’s tempting to play each cycle or verse using exactly the same chord shapes.

But, variety being the undoubted spice of life, you can actually vary the arrangement in a surprising number of ways in order to make things more interesting for yourself and, more importantly, your audience.

Ahead are five tips that are sure to breathe new life into your 12-bars.

For more blues advice, take a look at our 10 next-level blues chords and 18 ways to improve your blues guitar tone.

Electric Guitar Week is brought to you in association with Fender. Check out the Electric Guitar Week hub page for more tips and tutorials.

Don't Miss

18 ways to improve your blues guitar tone

Play guitar like Robben Ford: a masterclass from the man himself

1. Seventh heaven

The dominant 7th chord is the staple of blues arrangements – it’s everywhere. The restless nature of this particular chord is the backbone of a blues and adds the right touch of necessary drama to any blues song.

To hear this for yourself, try playing a blues 12-bar all the way through using straight major chords. It no longer sounds like ‘your baby done left ya’ – more like you’ve just won the lottery and have decided to spend the rest of the day watching TV in bed! Not the mood we’re trying to create…

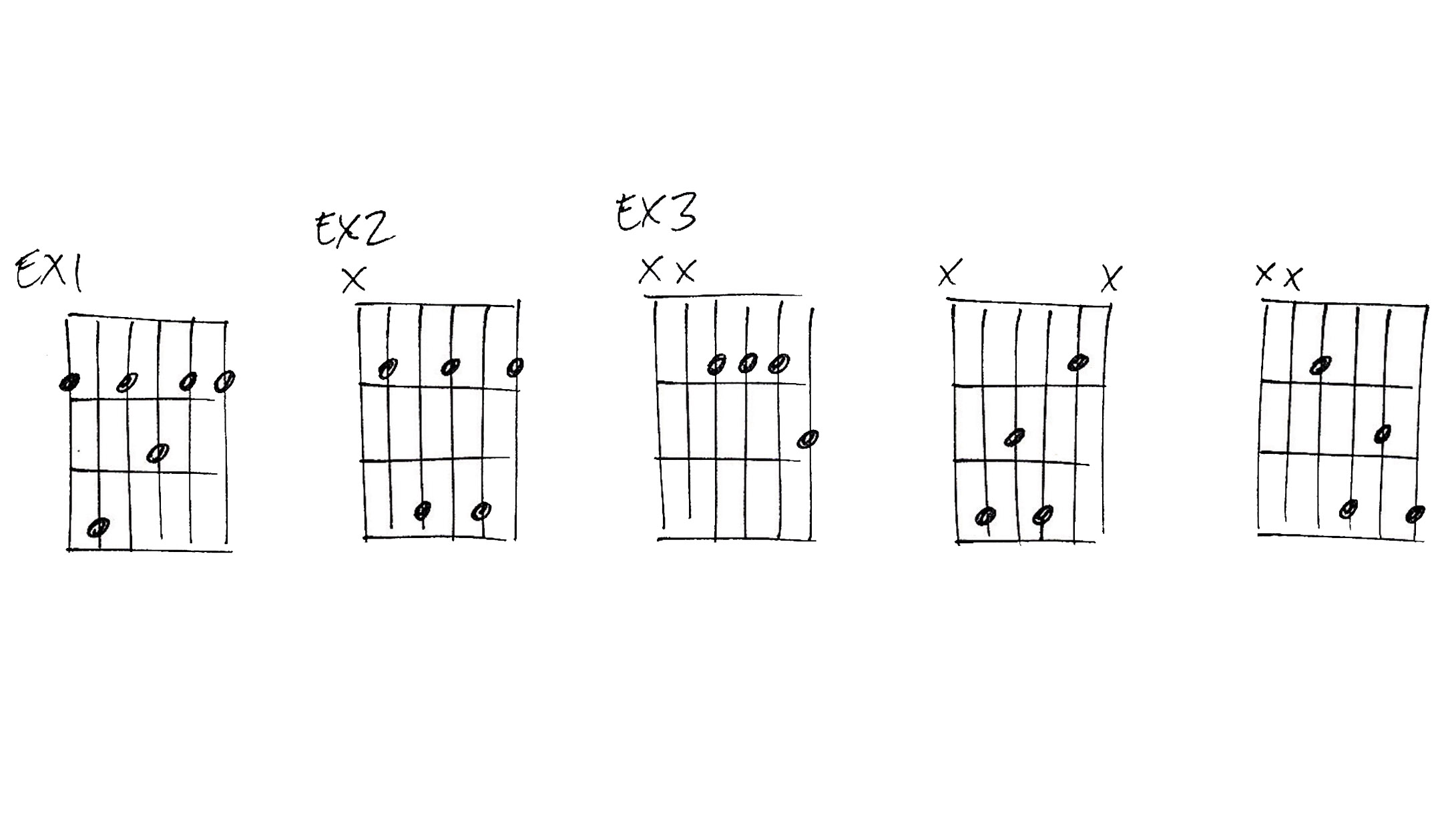

So, if the dominant 7th is so important, why is it we always seem to default to two versions of it? These two, in fact (Ex 1 and 2). They’re perfectly fine, but the dominant 7th story doesn’t end there – far from it.

The first thing you need to bring a bit of variety to your blues rhythm playing is an armoury of different 7th shapes to work into your playing. Try a few of these as substitutes – they’re all movable shapes and so all you have to do is move them around and voila, everything suddenly sounds more varied and interesting (Ex 3).

2. The devil's in the detail

When we think about conveying harmonic information, it’s no wonder that we might first reach for a satisfying six-, five- or four-note chord as an accompaniment.

After all, the theory books tell us that there are three notes in a major chord and so there must be four in a dominant 7th, right? Absolutely correct, but what are rules if not for the observance of fools and the guidance of wise men?

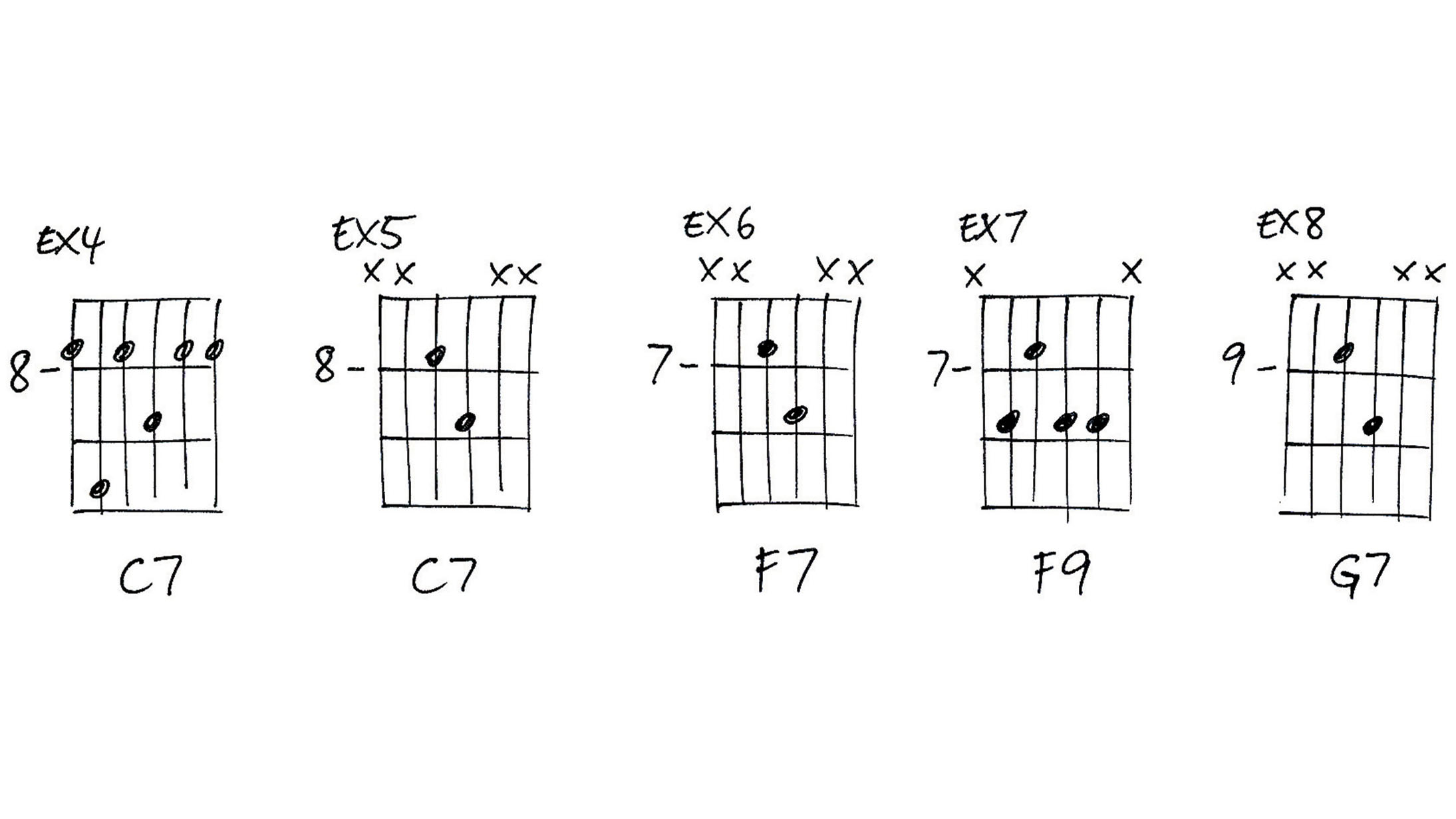

Here, we’re going to do things slightly differently. Take a look at the C7 chord in Ex 4: it’s a regular barre chord on the 8th fret, but if we strip it right down, we get the two notes in Ex 5. These are the 7th and the maj 3rd and the interval they form is the b5th – the so-called ‘devil’s interval’. This is the part of any dominant chord that demands resolution and gives the chord its urgent, unfinished nature.

It might not sound too pretty by itself, but watch what happens next in Ex 6. Looks exactly the same doesn’t it? Let’s fill in some detail – see Ex 7. Magically, it has transformed itself into an F9 – exactly the chord we need to continue our blues in C.

Once again, we’ve cut it right down to maj 3rd and dom 7th, but wait, it gets even more interesting when we do this (see Ex 8). If you guessed that this is a two-note version of G7, you’d be spot on.

So, we can play an entire blues just using two-note versions of the chords we need to make it work. Absolutely essential for those moments when you want to pull everything back, drop the level right down and get into some heartfelt, downhome blues!

3. Sometimes more is better

We’ve seen how it’s possible to cut a blues accompaniment down to two-note chords, but how about looking at things from the other end and actually thinking about how we can make them more interesting by adding notes, rather than subtracting them?

Just the tiniest amount of music theory tells us that dominant chords belong to a particular musical group and are distinctly different to majors or minors. They sound different and they function differently in music, too.

So, given that they are a family, we can actually swap a dominant 7th for any other chord from the group with the same root without losing any of its essential character.

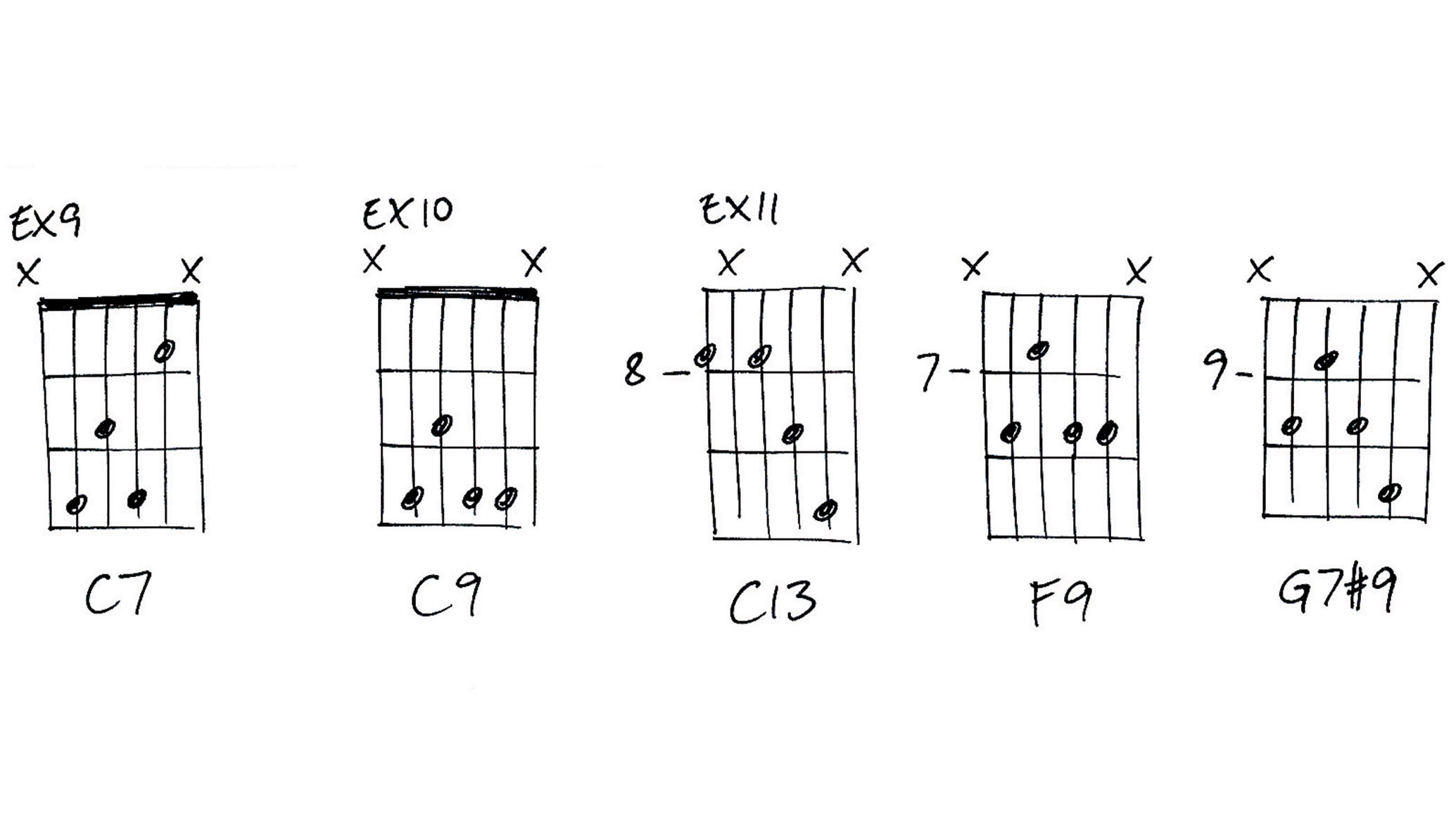

The most common substitution is to take an ordinary C7 and turn it into a C9 by adding a D note (Ex 9 and 10). It may sound different, but it’s performing the same job; it’s just an alternative colour.

Taking this idea forward, it means you can experiment with any dom 7th chord in place of a regular 7th and come up with an alternative effect. Try this (Ex 11): it’s a C13 moving to an F9 and a G7#9 – instant sophistication!

4. Slip slidin' away

Another way of adding a little bit more interest to any chord change is to slide into it from a fret above or a fret below – all it takes is a little bit of practice and it can really give your blues that professional sheen.

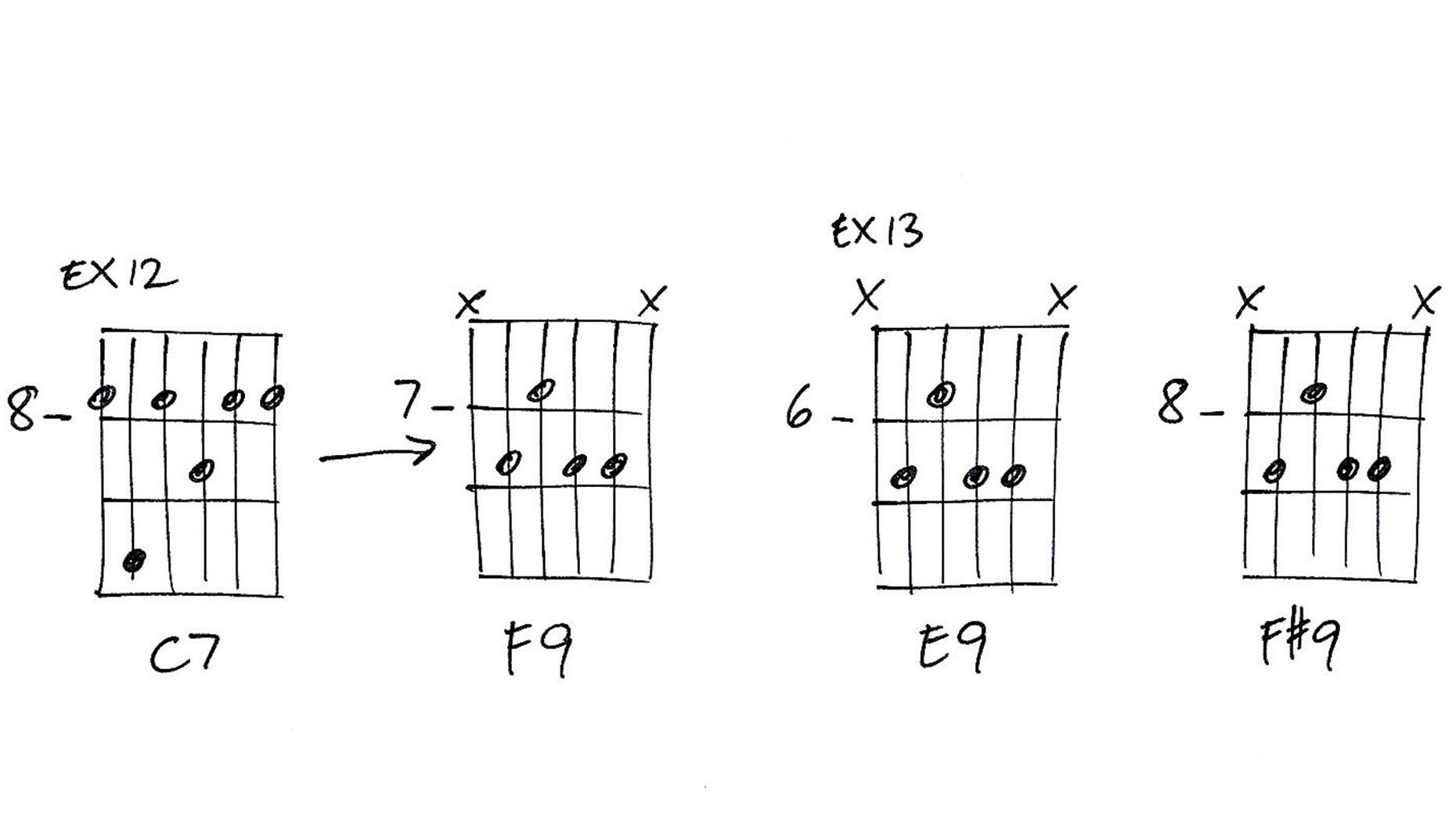

Let’s return to our blues in C for a moment. We’re on the 8th fret and we’re changing from the C7 to the F9 (Ex 12). Instead of going straight for the F, let’s take a more scenic route and hit E9 first (Ex 13). All you have to remember is to play the E9 at the very end of the bar so that the F9 comes in on the first beat of the next – otherwise things won’t sound very good at all!

Alternatively, you can perform a similar side step by going into the F9 from F#9 (Ex 14). Be sure to play the F#9 before the first beat of the bar in order to avoid dirty looks from the rest of the band…

5. Add a little jazz sparkle

To many people, ‘jazz’ is a dirty word and has no place in the blues vocabulary. But a great many will listen to the blues playing of guitarists such as Robben Ford and be amazed at just how many chords he can pour into the 12-bar blues format.

If you don’t know what we mean, just check out the rhythm part to Ain’t Got Nothing But The Blues from Robben’s Talk To Your Daughter album and report back. It’s a long way from the Mississippi Delta and the pure country blues idiom, perhaps, but you have to marvel at the effect an expanded chord knowledge can bring to a simple blues.

Of course, you needn’t go quite that far just to bring a whiff of class to a blues harmony or rhythm part. Sometimes, all it takes is a little twist to add a flourish.

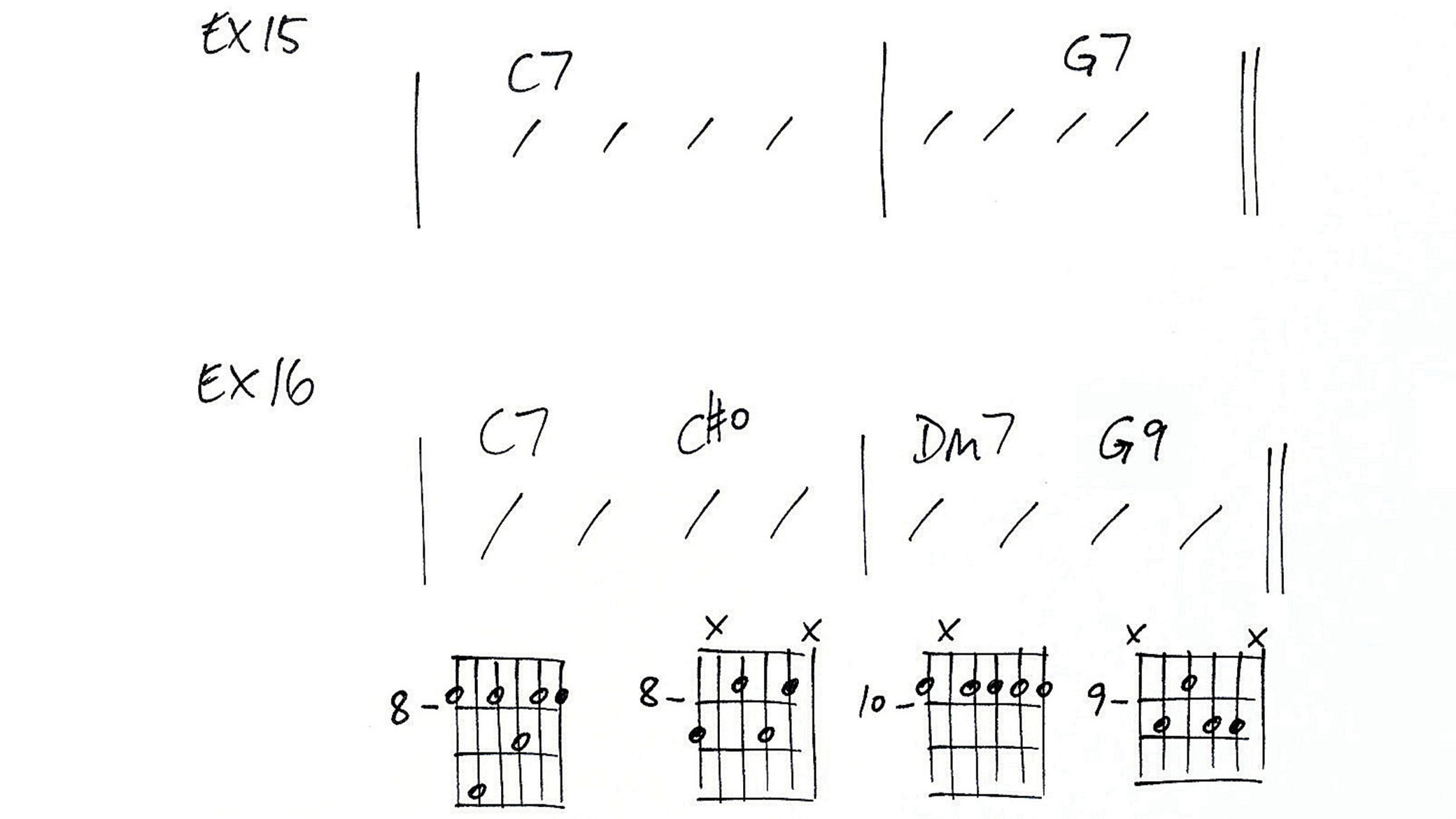

Let’s take the last two bars of a blues: normally, it would comprise simply this (Ex 15) – just the C7 rising to the G7 to herald the beginning of the next cycle of 12 bars. What if we introduce a little movement here?

Try this (Ex 16). Here, we’re going from the C7 to C# diminished, then on to Dm7 and G9. It’s smooth, classy and won’t upset anyone soloing over the top as it’s totally house-trained and pentatonic-friendly!

Don't Miss

18 ways to improve your blues guitar tone

Play guitar like Robben Ford: a masterclass from the man himself

Guitarist is the longest established UK guitar magazine, offering gear reviews, artist interviews, techniques lessons and loads more, in print, on tablet and on smartphones

Digital: http://bit.ly/GuitaristiOS

If you love guitars, you'll love Guitarist. Find us in print, on Newsstand for iPad, iPhone and other digital readers