MusicRadar Verdict

An analogue-sounding DAW with an easy-to-use mixer and a flexible audio routing structure.

Pros

- +

Unlimited track and plug-in count. Built-in EQ. Great value.

Cons

- -

May cause the occasional crash.

MusicRadar's got your back

Harrison Mixbus 2.0

Harrison Mixbus 2.0

Harrison Mixbus 2.0

Harrison is an American console manufacturer with a long history of outstanding achievements. Countless hit records (Michael Jackson, Queen, ABBA, Led Zeppelin to name a few) have been recorded and mixed on Harrison consoles since 1975.

The company, however, maintains a particularly solid reputation in film mixing, having installed some of the largest analogue and digital film consoles on the planet in the best dubbing theatres.

"This is a very musical EQ - the Q narrows with the gain increase, modelled on Harrison consoles."

The Mixbus is Harrison's attempt to pour its expertise into a dedicated DAW.

Against the stream

Mixbus was developed in partnership with Ardour, and crafted as a Harrison-style, custom version of its DAW. This is an unusual choice - Ardour is an open source, collaborative software development, but for this reason it's easily adaptable and draws from a solid userbase, all plus points for a new product.

Mixbus also relies on JACK - a low-latency, free audio server, currently available for Linux and OS X. JACK works as a patchbay within Mixbus, but also sets up an audio network with any other CoreAudio compatible application, allowing you to exchange audio between them.

At present, Mixbus can only be purchased as a download from Harrison's website. Only two files are supplied: an installer and an authorisation file. Linux users will need to source JACK separately, while OS X users will find it in the installer bundle.

JACK must be installed first, as it provides the backbone for the DAW, and launching Mixbus will start it up. In OS X, Mixbus will scan and recognise AU and LADSPA plug-ins on the system. VST support is under development. Linux users can also use LV2 plugs instead of the OS X-only AU.

Working with Mixbus

As first time users of Mixbus, we found the software fairly familiar to use. Mixbus could be operated with a two-button mouse (a standard Apple Mighty Mouse just won't do - right- clicking is the only way to access essential pop-down menus), but a three-button mouse with scrollwheel is highly recommended.

There are only two main windows - an Editor and a Mixer. The Editor features the channel strip for the currently selected track on the left and timeline, markers, transport and editing options at the top of the screen.

"It's hard not to like Mixbus - Harrison has done a great job with it - its few quirks are easily forgiven."

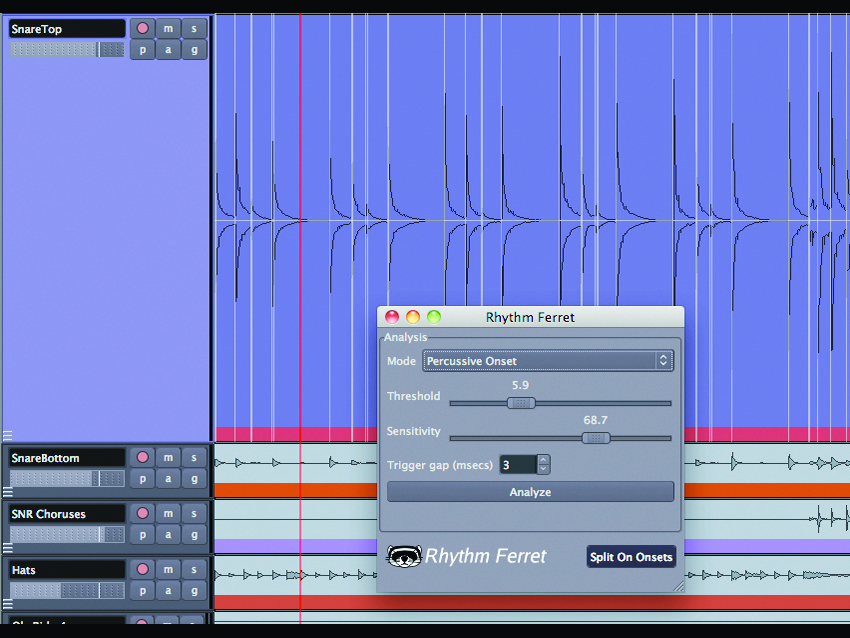

Audio tracks follow a conventional horizontal arrangement, and automation data of all controls and plug-ins is either superimposed or displayed as additional streams beneath each waveform.

Transport and editing options are all laid out at the top of the page. we happily discovered that the Editor window can be expanded to full-screen without any framing, menu bars and transport controls, thus reclaiming an extra 15-20% of space for editing-intensive sessions. A collapsible sidebar deals with region management, tracks show/ hide and edit groups.

Tracking with Mixbus is a breeze. Creating tracks sequentially defaults to the available physical inputs on the system. Before starting, best to check that the system isn't recording at 32-bit floating point if you need PCM audio, as this is the factory default.

Each channel supports direct outputs, all configurable using JACK. This effectively turns Mixbus into a multi-track recorder if the system has sufficient I/O. Track channels can be set in tape mode, making recording destructive when overlapping.

There are playlists and layer management, and key- commands can be customised for those like ourselves who are happy with the same set for all DAWs. One slightly confusing issue is with track grouping - the Editor and the Mixer run separate groups, and they cannot be copied across.

Also, playlists can be named but the name doesn't translate to the audio files, which will still bear the track name. Only renaming the channel strip will affect the file name.

The Mixer is just like a real console - it has embedded EQ, dynamics and sends. It is apparent that the idea is to give the user an instant knob-per-function approach.

The Mixer comes pre-loaded with one master fader and eight mix busses. Each of these boasts an analogue-style VU-meter, which indicates the amount of tape saturation introduced by the adjacent control knob, and is a definite vibe-setter.

Mono or stereo mixer channels and additional busses are user-definable and can be added without restriction to their number except for the available CPU power - our old Intel laptop managed to play 100 mono channels at 44.1KHz 24-bit with the CPU peaking around 95%, showing a very efficient use of the available resources.

Each channel features a three-band semi-parametric EQ with a high-pass filter. This is a very musical EQ - the Q narrows with the gain increase - modelled on Harrison's heritage analogue consoles.

Mix buss channels and the master fader have a three-band stereo EQ with fixed frequencies, shelving low and high and bell midrange, which we found excellent for adding general colour.

Each of the eight mix busses has a corresponding post-fader send knob on every channel, which can be used for effect sends or for sub-mixing. Curiously, the mix busses and the master fader do not scroll in the Mixer window, although mix busses can be hidden or shrunk.

The remaining portion of the screen is available for scrolling through the user-definable tracks and busses. Each channel, mix buss and master have a simple but very effective dynamics section, which can be set as a compressor, leveller or limiter.

The built-in compressor and limiter are extremely good despite their simplicity, and are comparable to those found on real analogue consoles.

The mix busses and the master fader also feature tape emulation. This is always inserted, and used sparingly can add some analogue feel, though at extreme settings it introduces pronounced distortion and dullness - much like real tape. The master fader also sports a brickwall limiter with look-ahead function.

Session notes

There are a lot of cool things about Mixbus. For a start, it sounds great. It's not a precise engineering tool like Pro Tools, but it makes it easy to get a good sound with little effort. The association with JACK offers almost endless possibilities and places Mixbus solidly at the centre of a virtual studio.

A nice touch, currently not automatable, is the shuttle speed control capable of real-time forward and reverse audio playback at up to 8% speed (two octaves) either way - it's just great fun.

There are of course some letdowns. Using a lot of AU plug-ins can lead to nasty crashes, especially when using less-reputable or obscure ones. Version 2.0 introduced Plug-in Control Sliders, and there's still some debugging to do.

It's also disappointing that user-created busses aren't latency-compensated - if this can't be done, we would personally give up this feature to gain more mix busses. Coming to control surfaces, only those following the Logic Protocol or generic MIDI ones are supported.

It's hard not to like Mixbus - Harrison has done such a great job with it and its few quirks are easily forgiven, especially considering the very small price tag.

If you want a distinctive sound without too much fuss, Mixbus is almost unbeatable, but it cannot compete with more professional solutions, especially given the lack of in-depth production tools.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“He seems to access a different part of his vast library of music genre from the jukebox-in-his-head! This album is a round-the-world musical trip”: Joe Bonamassa announces new album, Breakthrough – listen to the title-track now

"The Rehearsal is compact, does its one job well, and is easy to navigate without needing instructions": Walrus Audio Canvas Rehearsal review

“The EP635 delivers the unmistakable high-gain aggression and clarity that Engl fans love”: Engl packs its iconic Fireball head into a compact dual-channel stompbox with onboard noise gate and IR support