Why imperfection is the secret to making better music

None of us are perfect - so why should our music be?

Gus Nisbet is a guest contributor from Echoic Audio, an award-winning music and sound design studio working across motion, film, adverts, and art. Based in Bristol, UK, Echoic’s engineers are specialists in music production and sound design, with clients including Nike, Adidas, Dyson, ITV, Mercedes and Jaguar.

Our fascination with music as a species has long evaded scientific rigour. Somewhere between pattern recognition, social bonding, and a deep-seated yearning to analogise the human condition lies an explanation of why we love it.

We create deep connections to the world around us through music. It gives lifeblood to thoughts that elude capture in language. Its subjective experience is indescribable.

As the late, great Frank Zappa said, “writing about music is like dancing about architecture”. Nevertheless, we do it anyway - that's a testament to the power of great sound; we’re compelled to talk about it, however empty and misguided that may be.

Soundtracking the modern age

Although its emotional influence is difficult to explain, musical diversity has skyrocketed in the 21st century alongside technological innovation. Whether it’s streaming platforms, production tools, marketing and advertising, movie soundtracks, or simple fun, the demand for creating and consuming new music is huge. Spotify is innovating algorithmic playlists, Ableton is delivering production power to young composers, and Amazon Alexa is paving the way for an ‘audio-first’ world.

The democratisation of technology means we all have access to the tools to become a modern-day Mozart or next-gen John Lennon, which is great for those who might not have discovered a musical talent in bygone eras. But with powerful technology, comes great responsibility (Spiderman, anyone?).

New production tools have given rise to many different sounds and styles, and often these tools have the power to make things sound better. Mighty VSTs, imagers, doublers, exciters, multiband compressors, noise reducers, intelligent waveform analysers, auto-masters, all aiding the goal of making music crisper, cleaner, wider, fatter, smoother, dirtier… the list goes on. Any professional composer will have first-hand experience of this.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But they don’t always make music better. Sometimes, but not always.

Production tools: friend or foe?

Don’t get the wrong impression, at Echoic Audio we’re not luddites. We’ve produced award-winning music and sound design for animators, directors, multimedia artists, advertising agencies, you name it. We love drooling over powerful synthesizers and obscure guitar pedals, oscillating through a mixing desk with more controls than a pilot’s cockpit. Technology powers Echoic’s creative output.

Yet, as producers, we’re easily tempted into using these tools to eliminate every crackle, remove every pop, and quantise every hi-hat. And that’s fine for music for shopping centres, or grandma’s birthday. But often this leads to sterilised caricatures of what was originally intended. The original concept - the raw idea - becomes lost, hidden beneath computerised ‘perfection’.

Dr. Diana Omigie, a cognitive neuroscientist at Goldsmiths, University of London has been conducting research into music-induced emotion to understand these ideas more fully. She argues “what could be considered imperfections (slightly irregular timing in music for instance) are often perceived by listeners as being more ‘expressive’. Empirical research shows expressivity is a major contributor to aesthetic appeal.”

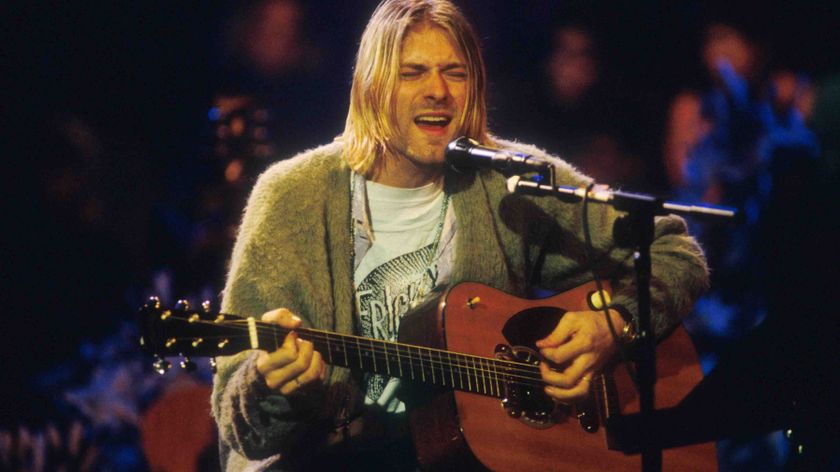

Take editing vocals, for example. You record several takes; they sound good but they’re not perfect. You tune parts, quantise sections, remove breaths. Now you’re left with a ‘perfect’ version of the original recording.

Does it sound good? Possibly not. It might sound thin, mechanical or slightly alien. By removing slight pitch variances you’ll lose the subtle chorusing and thickening effect that occurs naturally - the harmonic complexity will vanish, and so will the expressiveness. If the original recording needs that much manipulation, you should record it again rather than edit it after.

Composer vs computer

Generally speaking, technology is not artistic - it’s the person controlling the tech that provides the artistry. Look at examples of AI attempting to write poetry and you quickly realise creativity is not an innate skill of new technology (the internet is abound with hilarious examples).

Adam Hammond, professor of English at the University of Toronto, says that it’s easy to feed a machine thousands of examples and yes, it will learn rhyme and structure, but “It’s much, much, much harder to train it to have an opinion, or a feeling, or a desire, or a story to tell”.

Wired even published an article based on Hammond’s attempt to use AI to generate rules for writing a story.. Even though the story was written by well-known writer Steven Marche according to the rules generated by the AI, the Editor in Chief of Random House concluded, “That stuff doesn’t sound human”. When it comes to machines being creative, the general consensus is that something is always missing.

Creating an intimate context

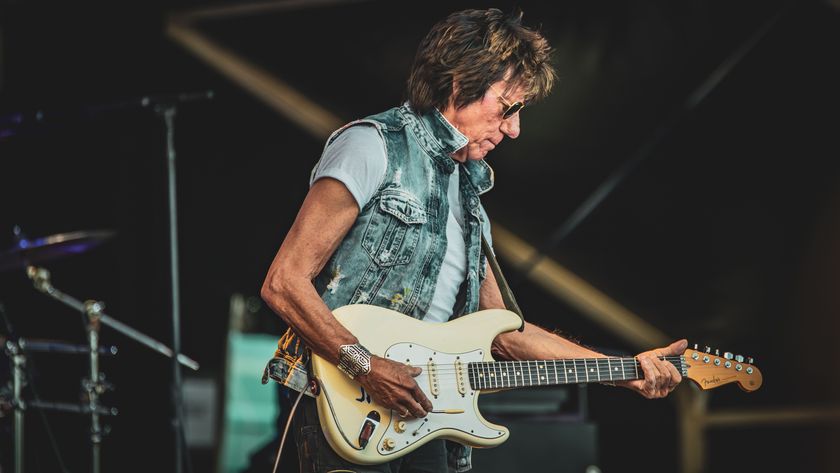

Imperfections give context to a recording. You get a sense of the individual musician playing the instrument - the skill and passion the individual brings to a recording session, and the unique reproduction of the idea, born from the artist.

Led Zeppelin are a great example. From squeaky bass pedals to detuned strings, their music is rife with imperfection. Even their remasters sound beautifully rough.

Bon Iver also works to this effect. His new album I,I is littered with recording context. You can hear feedback, creaking and voices in the background throughout - the raw, intimate performance bleeds through. Floating Points even starts his track King Bromeliad with the sound of a clubgoer outside a venue hearing the track muddy and muted before a door opens and the track switches from the ambient, contextual reproduction to the polished studio recording.

At Echoic Audio, our own homage to this tradition can be heard in the soundtrack we produced for the Main Titles of renowned creative festival, OFFF Festival (Barcelona), directed by Chris Bjerre. Breaths and unwanted vocalisations can be heard throughout the final section, and the unedited sound of the pianist’s chair creaking is audible too.

When recording different audio tracks, minimising bleed is a means to an end; it shouldn’t be an end in itself. It’s worth taking a step back before diving in to clean a recording. Ask yourself, is this necessary for my end goal, or is it just a production habit?

Another prominent example of an artist embracing imperfection is Matthew Herbert, the esoteric, house music legend who now scores international movies. He fiercely advocates producing music in the most human, unadulterated way possible. He has what he dubs a Manifesto of Mistakes, encouraging imperfections and accidents throughout the compositional process. Point 5 of his manifesto states: “The inclusion, development, propagation, existence, replication, acknowledgement, rights, patterns and beauty of what are commonly known as accidents, is encouraged. Furthermore, they have equal rights within the composition as deliberate, conscious, or premeditated compositional actions or decisions.”

Unpredictability and imperfection

Even the most electronically-driven music is littered with imperfections. Artists like Aphex Twin, Squarepusher, Venetian Snares and Skee Mask are all prime examples. To argue their music isn’t born from an incessant desire to experiment and manipulate sounds in ways unforeseen is to miss the point. That’s why they’re so original, and why they’ve changed the musical landscape forever (check any of Aphex Twin’s huge discography for evidence).

Dr. Omigie’s research helps us understand why we might enjoy this kind of imperfect, unpredictable music. She states, “we have a predictive model of what we are hearing. Events we haven't been able to perfectly predict generate so-called prediction errors. Prediction errors indicate to us that our mental ‘model’ of the world can be optimised.

“Generally, we like to be in situations where our model can be improved (ie, where we can learn) as it makes us more adaptive to the world, and so we will seek to be in those places.”

Thus, seeking out unpredictable, experimental music is a key motivation when it comes to our aesthetic appreciation of new music.

Music and evolution

Innovation develops from experimentation. This is true at basic levels. The world is only the way it is through millennia of experimentation. Every organic process is a product of tireless unpredictable mutation, where some changes propagate and others do not.

From single-celled organisms to complex ecosystems, it all began with an error. And then another error. And another. From this chaotic proliferation of mistakes everything emerged, including us. We’re imperfect beings, we make mistakes all the time, we can be clumsy, aimless and indifferent. This is the wonderful diversity of ‘being human’. From pure elation to sinking depression, our inconsistencies produce works of art, capturing complex emotions as we plumb the depths of the human psyche. Our appreciation of music is wholly entangled with our imperfections.

There is no definition of ‘perfect’ in music. This reiterates the initial point that the subjective experience of music is indescribable. We all experience it differently; it becomes personal. And with that comes unending variation.

Look at the mixing process, for example. There is much variety of a ‘good mix’. Yes, there are some 'dos and don'ts’, but listen to any record collection or online playlist - the mixes of each track are different, they’re never the same. Some are light and airy, others are deep and heavy, with everything in between existing somewhere.

That’s a crucial takeaway: ‘Good’ music is different to ‘perfect’ music (and as identified, there is no such thing anyway). ‘Good’ encapsulates a wealth of different experiences, approaches, and concepts. ‘Perfect’ implies a specific, universal outcome with no room for innovation. If we were perfect beings, we wouldn’t be changing our environment at the rate we are, and we certainly wouldn’t have many of the issues we face today.

One step ahead

Our modern age is characterised by an incessant drive to achieve perfection. Whether it’s creating the perfect Instagram profile, achieving perfect grades in school, streamlining industrial processes, or advertising campaigns promising convenience, there’s a compulsion to optimise, to be more efficient, more productive, more perfect.

But efficiency and perfection leave no room for unexpected consequences, no room for alternate possibilities. They funnel us down a route laden with specific, orchestrated outcomes.

When making your own music, bear this in mind. Imperfections pique our curiosity, making us more engaged. To be truly original you have to deviate from the norm, you have to experiment, you have to be willing to embrace imperfections. If all else fails, ensure whatever happens during the creative process, you embrace your own imperfections. After all, it’s your imperfections that make you human, and until machines master the art of humanity, you’ll be one step ahead creatively.