What's so great about... Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God) by Kate Bush?

The music theory magic behind the revived '80s classic that's found a second life in Stranger Things

Here at MusicRadar, we acknowledge that Kate Bush is a singularly talented artist who doesn't necessarily need a feature in a TV series to be appreciated by the world.

Nevertheless, it would seem that Kate and the Duffer brothers - creators of Stranger Things - have a mutual appreciation of each other's work, a fact which has culminated in Running Up That Hill landing in a key scene from the hit Netflix show's recently aired fourth season.

Like a portal to the upside-down, Stranger Things has opened up Kate's work to a whole new generation of fans, and resulted in her first number one single since 1978's Wuthering Heights. So what is it about Running Up That Hill that lends it such enduring appeal? Read on as we loosen the song's nuts and bolts and open up the hood of this 80's classic to find out what gives it supernatural powers.

The backstory

By 1985, any successful recording artist worth their salt had invested in a hugely expensive, cutting-edge computer-based sampling instrument from Australia known as the Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument). By this point, with four successful studio albums already under the belt of her kimono, Kate Bush was perfectly poised to quickly embrace this rapidly emerging new sampling and sequencing technology.

Escaping the pressure of expensive studio time ticking away by building her own 48-track home studio, fully equipped with all the latest gear, she could relax and create freely without fear of "Running Up That Bill". In the Fairlight, Kate found the perfect tool she needed to explore new realms of sound creation, and its subsequent heavy inclusion on the Hounds of Love album is a key factor in why Running Up That Hill still sounds as evocative and characterful as it does today.

The personnel

Vocals, keyboards and production: Kate Bush

Drum programming and bass: Del Palmer

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Balalaika: Paddy Bush (Kate's multi-instrumentalist brother)

Guitar: Alan Murphy

Additional drums: Stuart Elliott

The arrangement

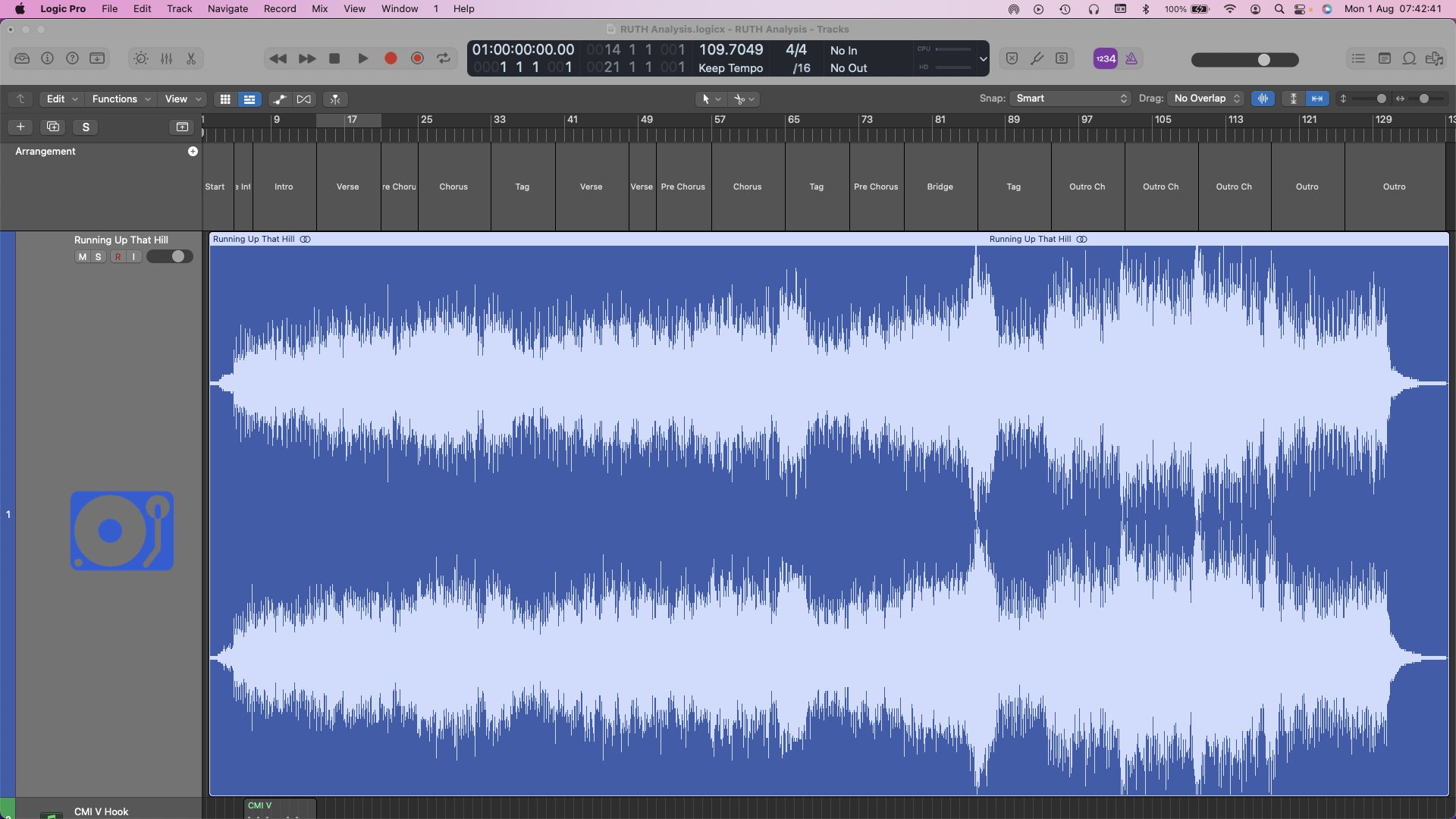

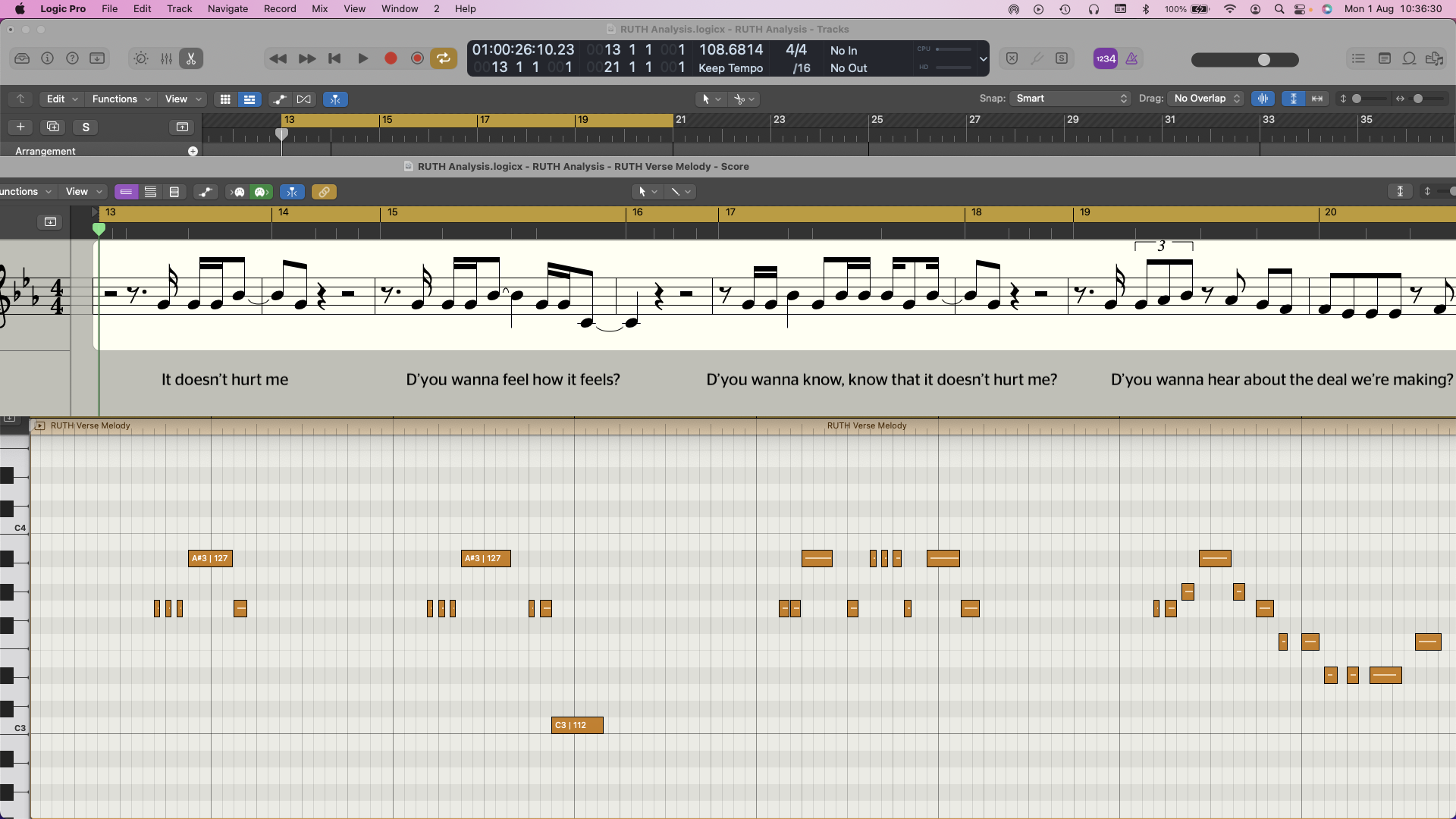

In what seems like a purposeful move away from conventional pop song structure, the first half of Running Up That Hill has an almost meandering feel to the arrangement, with uneven bar lengths that make it seem as if the chorus is jumping in a beat or two earlier than it should, the aural equivalent of a jump scare.

This is exacerbated by two things - at seven and eleven bars long, the two verses are not the durations we'd normally expect, which catches us unawares. Each of the two pre-chorus sections are also different lengths, at four and six bars respectively.

Secondly, the word 'if' (from the line 'if I only could') happens on the downbeat of the first two choruses, rather than two beats earlier as it does later on in the song for the outro choruses - for these later choruses, it's the word 'could' that occurs across the downbeat. The chorus sections are also unheralded by any kind of build or drum fill, which is unusual and adds to the jarring effect.

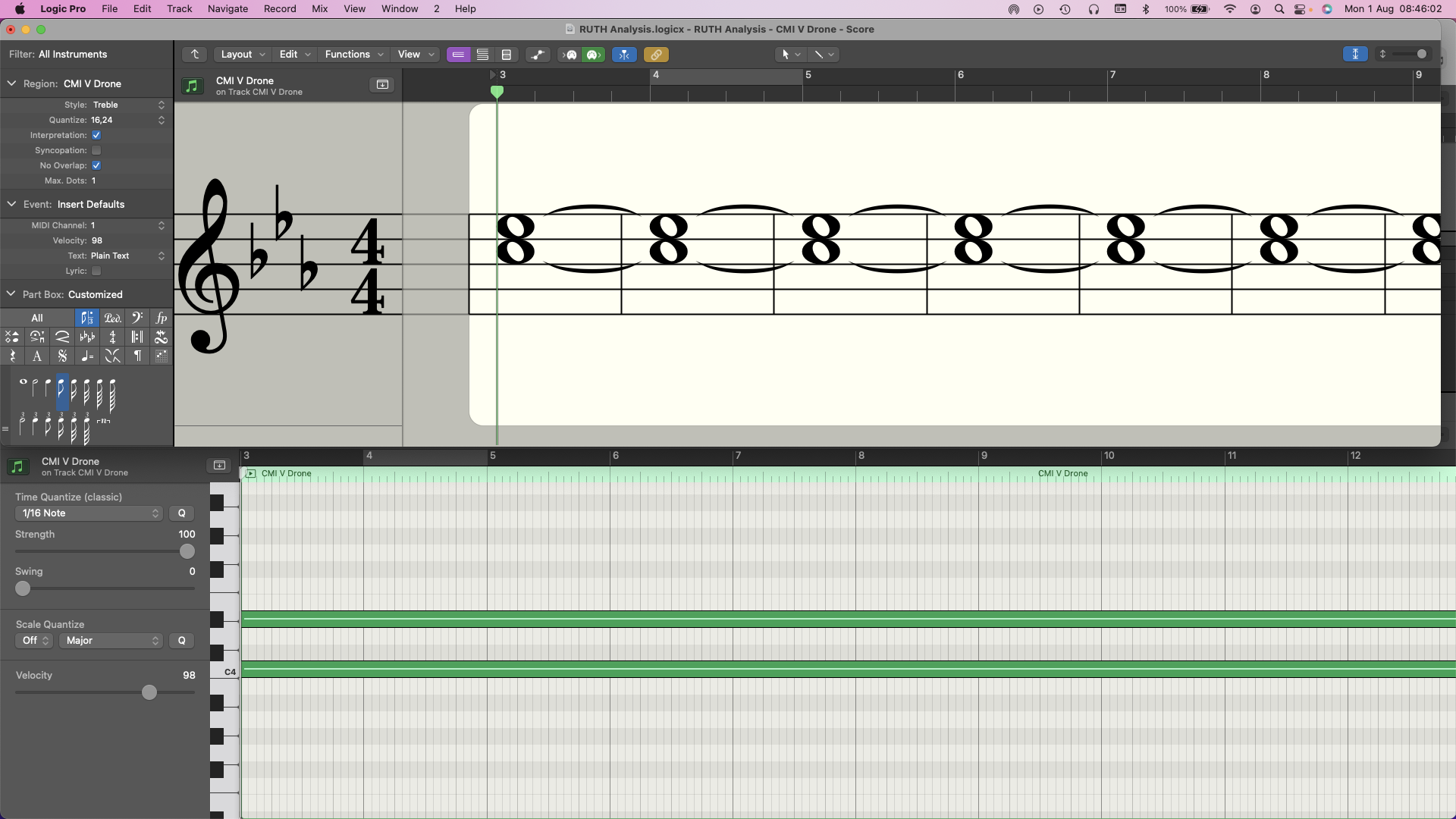

The drone

The first thing that marks out this tune as unique (and also the first thing we hear) is the constant synth pad drone that sustains unwaveringly throughout the entire song. Made up of just two sustained notes - C and Eb - this not only provides a solid clue that the song is in the key of C Minor, but also provides alternating tension and resolution as the primary chords shift beneath it.

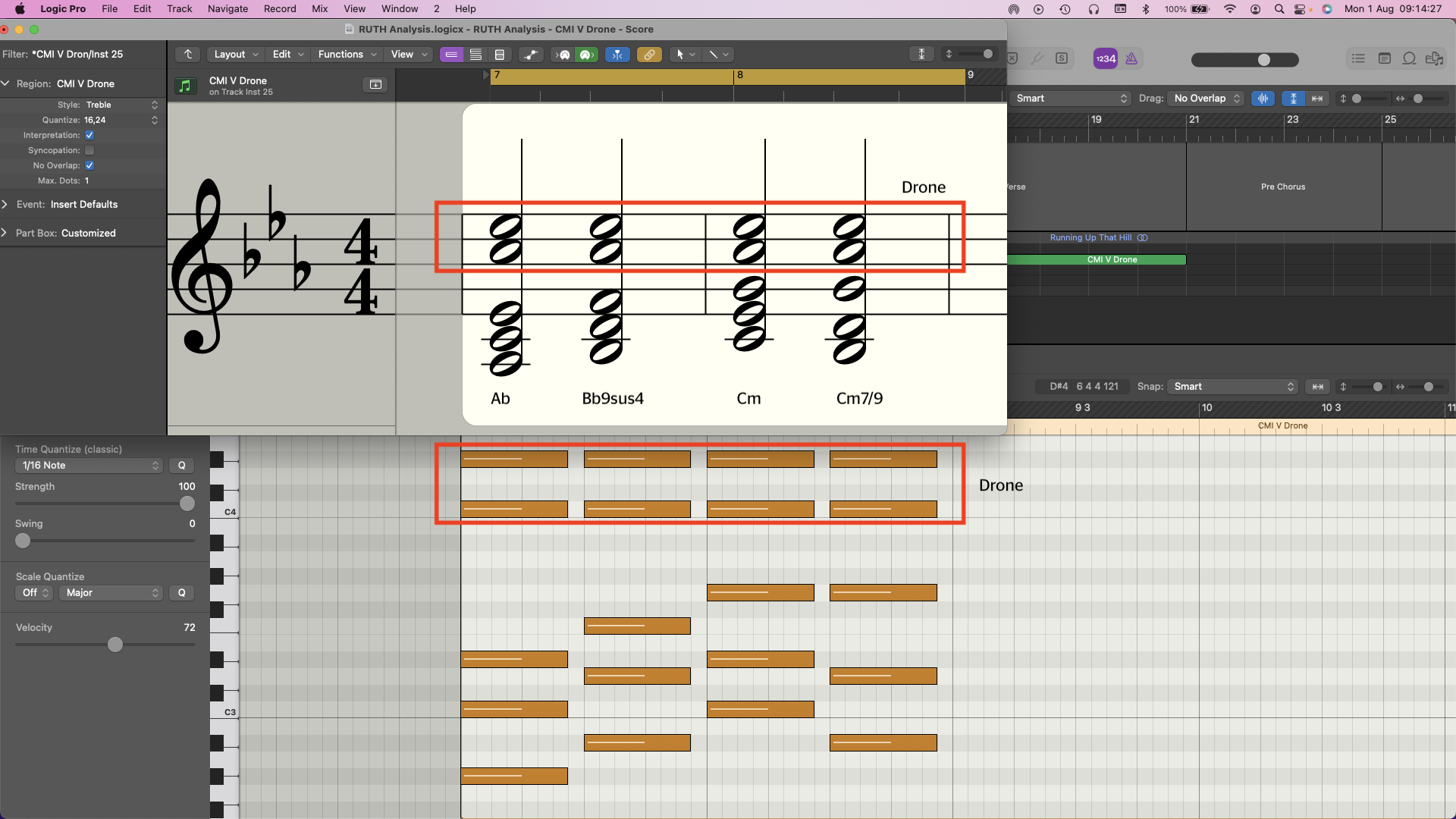

The chords

The rate at which the chords change in a piece of music is known as harmonic rhythm, and changing this up for different song sections is a great songwriting trick to maintain interest while keeping the number of chords used down to a minimum..

For example, in the song’s verses, the chords change twice in each bar, rather than once per bar as played in the intro and choruses.

The verse chords are Ab > Bb > Cm > Gm - which translates to a VI > VII > i > v pattern in the key of Cm.

On the face of it, these are just simple diatonic triads - three-note chords built from notes taken from the C Minor scale, which is the parent scale of the key of the song. However, when you combine these triads with the notes that the sustained pad is playing, the progression takes on a different tone altogether:

Ab > Bb9/sus4 > Cm > Cm7/9

The suspended and extended chords created by the combination of the drone with chords two (Bb) and four (Gm) add a feeling of tension - that Bb Major chord combined with the C and Eb of the pad makes it technically a Bb9/sus4, while adding those two notes to the Gm chord transforms it into a perceived Cm7/9.

The tension is resolved on chords one (Ab) and three (Cm) as both drone notes of C and Eb are found within both of these chords. The effect is a continuous cycle of tension and resolution as the chords progress.

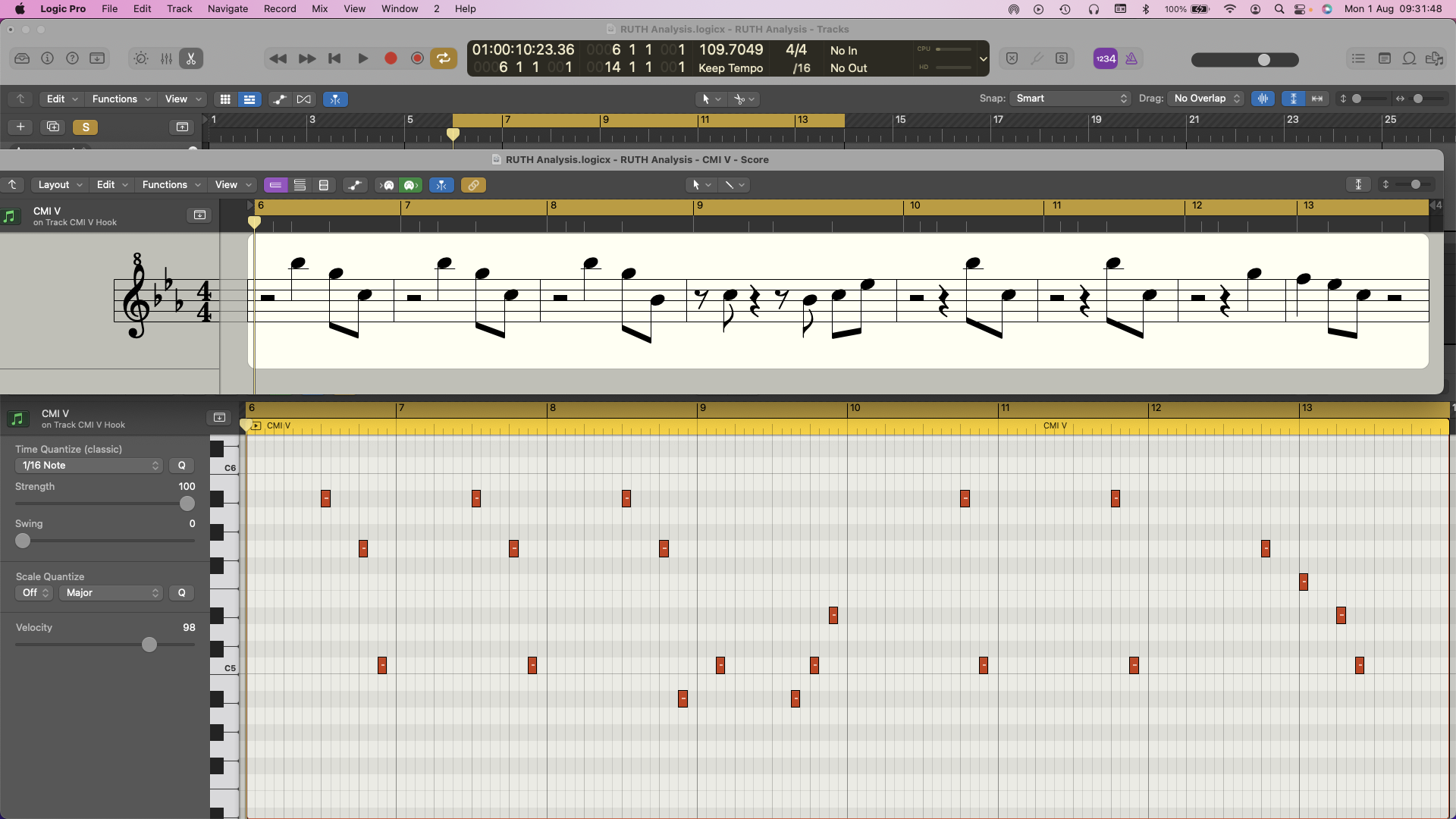

The sampled hook

Present in the intro, tags and outro sections, this famous and instantly recognisable synth melody is what most people associate with the song. Dripping with retro sampler cool, this hook is played by the Fairlight’s Cello2 preset, with the loop points of the sample set so that it has almost a slapback delay effect. The melody it plays mirrors the vocal melody, with its wide, minor 7th interval jumps from Bb down to C.

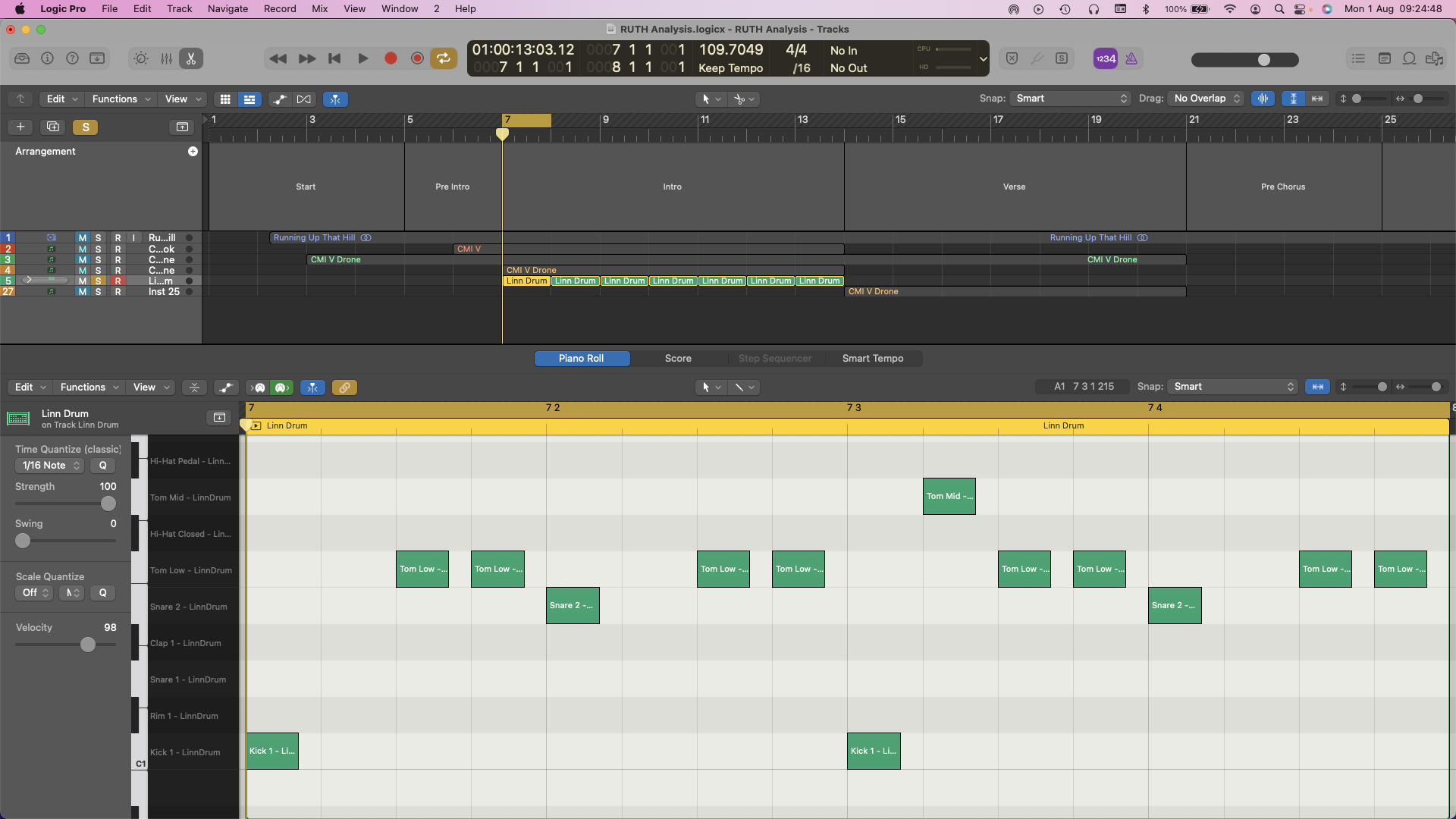

The drum pattern

Running at around 108 beats per minute, the pounding, tom-heavy drum pattern of Running Up That Hill was initially programmed on a LinnDrum drum machine by Kate's long-term partner and collaborator Del Palmer, with additional drums added later by Stuart Elliott.

We get a kick drum on beats one and three, a snare on two and four and those insistent toms hammering out the galloping beat in between. Interestingly, there are no hi-hats or crash cymbals at all in the pattern. Along with the pad drone, the same one-bar loop repeats for the entire length of the song, accented by overdubbed tom fills that occur towards the end of the bridge and across the outro choruses. These are thunderously loud and reverberant, presumably representing the 'thunder in our hearts' lyric.

Kate has stated in interviews that the track began life with her asking Del to program the part on the drum machine, after which she laid down the pad and synth hook from the Fairlight over the top. This might go some way towards explaining the unusual section lengths - it’s possible that the unwaveringly linear nature of the drum loop and pad as a backing track to write over, unpunctuated by fills or cymbals, could be what gave rise to the somewhat freeform nature of the song’s structure.

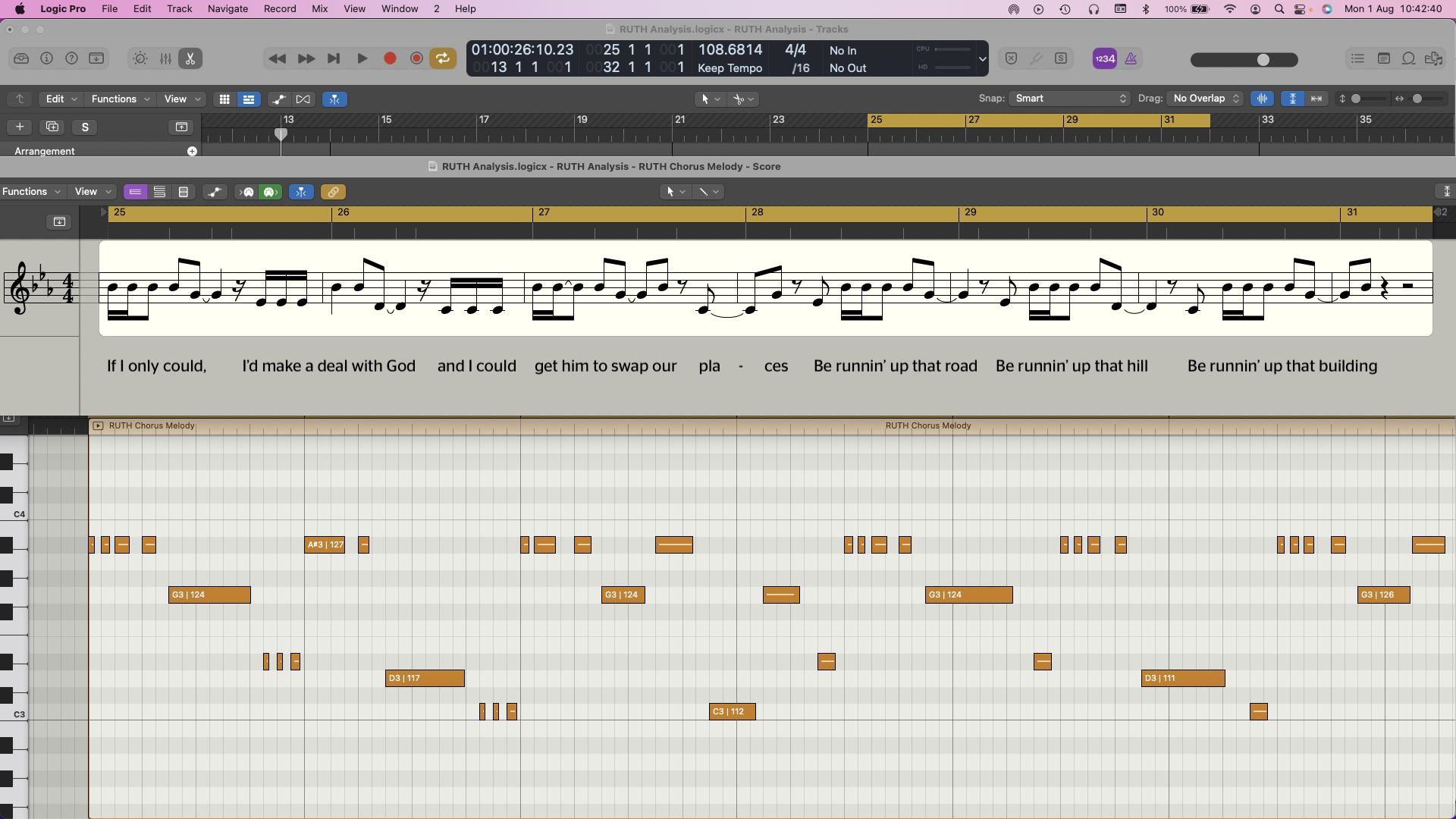

The wide melodic intervals

Kate has always been renowned for her unusual, twisting melodies that leap up, down around and sometimes even completely off the scale. The melody for Running Up That Hill is in the C Aeolian mode, which means that it’s made up of notes from the C Natural Minor scale. It contains some seriously wide intervals, most notably the minor seventh between the Bb of 'our' and the C of the first syllable of 'places' in the chorus. The D note on the word ‘God’ is very special, grating against the C and Eb of the drone and reinforcing the 9th in that Bb9sus4 chord.

The lyrical content

The song explores the relationship between a man and a woman, wondering what it would be like if they were each able to change places and understand the relationship from the other's point of view. How much easier would life be if we could fully understand one another's perspective through our own experience of it?

Kate is on top lyrical form here, with lines like 'there is thunder in our hearts' and 'not knowing that I'm tearing you asunder' highlighting the drama and unconscious trauma that can be present in a turbulent relationship. Making a deal with God to change places, as an alternative to making a deal with the Devil, is powerful imagery, suggesting that divine intervention is the only way left for the couple to truly understand each other. The presumed end result of the deal is compared to the blissful carefree naivety of running up that hill, with no problems.

The vocal effects

As the track gets more and more urgent and chaotic, with overdriven guitars and thunderous drum fills, the outro chorus repeats are peppered with multiple tracks of manic sounding, random vocal wails mixed in the background, adding a sense of unease and confusion as the track nears its end.

The synth and drum machine that powered Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill

As the track gets more and more urgent and chaotic, with overdriven guitars and thunderous drum fills, the outro chorus repeats are peppered with multiple tracks of manic sounding, random vocal wails mixed in the background, adding a sense of unease and confusion as the track nears its end. Meanwhile, in the last section of the outro, over a satisfyingly-resolved, sustained Cm chord, there's a detuned vocal doubling of the lead that has the demonic effect that only a slowed-down sample can offer. Since the Fairlight did not offer timestretching, this may well have been sung at a normal pitch but at double speed and then sampled and played an octave down on the Fairlight's keyboard to match the track's tempo, which would have achieved that sinister detuned sound at a speed matching the original lead vocal.

After just four bars of this intriguing effect, the pounding drums finally cease abruptly halfway through a bar, leaving just that ethereal pad to slowly fade away, the track ending in an exact mirror image of its beginning.

Dave has been making music with computers since 1988 and his engineering, programming and keyboard-playing has featured on recordings by artists including George Michael, Kylie and Gary Barlow. A music technology writer since 2007, he’s Computer Music’s long-serving songwriting and music theory columnist, iCreate magazine’s resident Logic Pro expert and a regular contributor to MusicRadar and Attack Magazine. He also lectures on synthesis at Leeds Conservatoire of Music and is the author of Avid Pro Tools Basics.