"I was standing crying at the synthesizer, so I pulled out a card and it said 'just carry on'. I did and created something I still like today": How Brian Eno's mysterious Oblique Strategies could help your music production and your life

"Use fewer notes", "Be dirty" or "Mute and continue": which Strategy will you use in the studio today?

Brian Eno's Oblique Strategies might well have been around since 1975, but nearly 50 years on we think they might be as relevant as ever, and not just for music production. So what are they and, most importantly, how can you use them in your music making (or, indeed, life)?

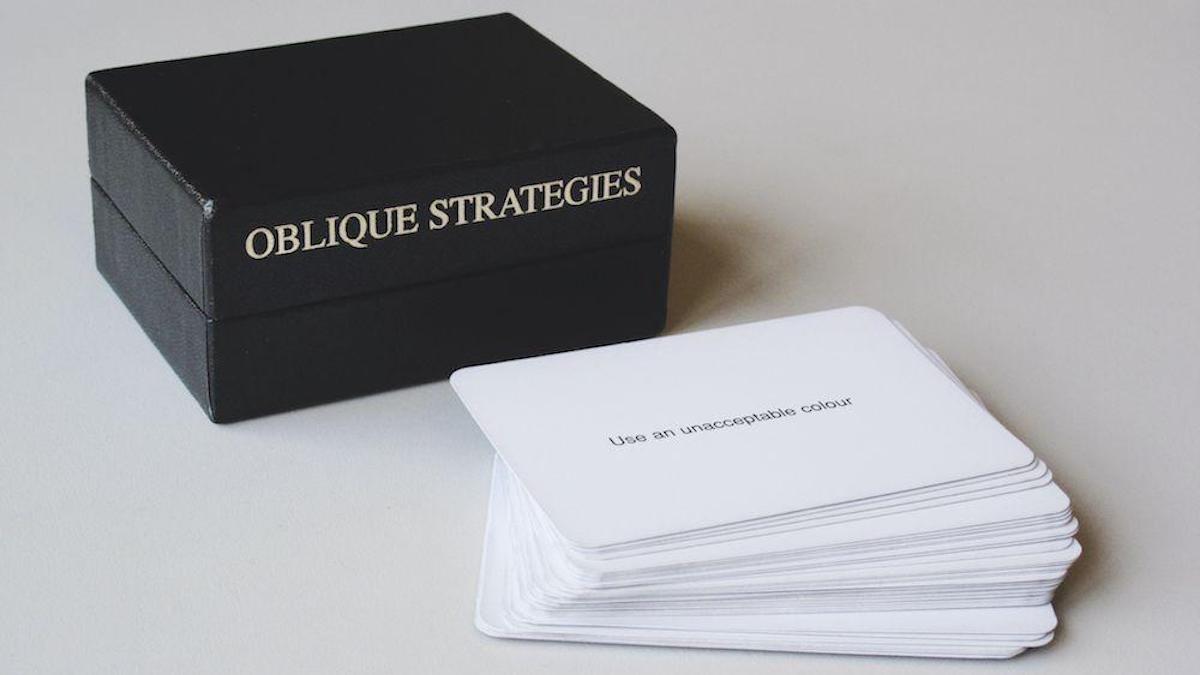

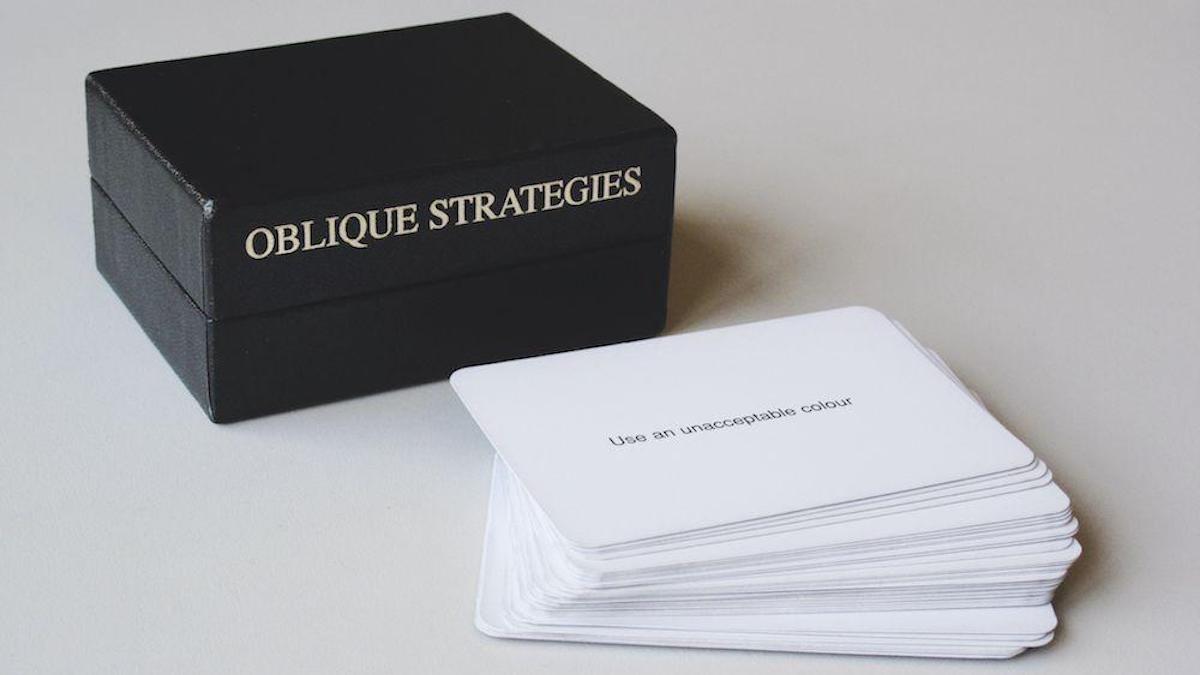

Coldplay have used them, as have Talking Heads and Bowie. That's because Brian Eno's Oblique Strategies have become something of a legend in studio circles, a set of cards with ideas for you to follow should you ever become stuck for inspiration while composing or producing. What you might not know is that a) the cards actually do exist, and b) they might well help you with your music making, five decades after they were conceived.

The concept was born at a time when studios costs were high and the pressure was always on to keep working. No time to waste, just pick a card.

Eno developed the Oblique Strategies idea along with the artist Peter Schmidt, apparently inspired by Edward De Bono and his Lateral Thinking books.

Oblique Strategies eventually became a set of over 100 cards, each with an idea, phrase or direction. The concept was that whenever Eno needed some kind of inspiration or a new way of thinking in the studio, he could literally just pick a card with the answer. It was born at a time when studios costs were high and the pressure was always on to keep working. No time to waste, just pick a card.

The cards might say 'repetition is a form of change' or 'cut a vital connection' or even, according to one Oblique Strategy source, 'get a neck massage'. Some are clearly easier to understand than others – we like 'what mistakes did you make last time?' , and 'take a break'.

Others can be interpreted in different ways – which is probably the idea – so make what you will of the likes of 'balance the consistency principle with the inconsistency principle' and 'go slowly all the way round the outside'.

Others still are frankly bonkers – again probably the point. What to make of 'you can only make one dot at a time', for example?

Eno first used the idea while recording the 1975 album Discreet Music when he realised that constraints could be better than freedom. In a 1981 interview he discussed the "assumption that if you remove all constraints from people they will behave in some especially inspired manner. This doesn't seem to be true in any sense at all – not socially, and certainly not artistically."

Instead, Eno started adding constraints, some of which became cards in the 115 Oblique Strategies.

In October 1994, Eno summed up the idea behind the cards to The Mix magazine: "Imagine you're working, things are getting difficult and the situation reaches an impasse. You keep trying things but they don't work, so it's you should ask yourself: 'What wouldn't I do?' 'What are the things I wouldn't think of doing?' You've already thought of the things you thought would work, but they didn't.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You should ask yourself: 'What wouldn't I do?' You've already thought of the things you thought would work, but they didn't.

Brian Eno, speaking in 1994.

"It's a little bit like when you've lost something and you go around the flat looking in all the obvious places where you might normally leave something. Clearly it isn't in any of those, so you then think about all the places you wouldn't usually think of looking. Chances are you'll probably find the object."

Eno then gave some examples: "Change instrument roles. Do something boring. Consult other sources, either promising or unpromising. Cut a vital connection - that's a very interesting thing to do because most pieces of music are based around some centre, like a drum track or a drone, which really holds everything together.

"Just try taking that element out of the music and see what happens. Suddenly, when you take it out you start to hear everything else that's there, and you may realise that some of it is redundant, obsolete or, even more interesting, that it stands completely alone and is in fact another new piece of music to develop."

Eno would successfully use the prompts on albums such as Another Green World and Before And After Science, although he would later stop referring to the physical cards as he claimed to have them all imprinted in his brain anyway.

I didn't pull them out lightly because I knew it could mean jettisoning whatever I was doing.

Brian Eno, speaking in 1988.

"Oblique Strategies were really a way of getting past panic by reminding myself that there were broader considerations than the ones I could remember in the studio", Eno told Music Technology magazine in 1988. "So when I got into a panic, thinking, 'where is this going? It's not going anywhere', I'd pull out one of those strategies and it would tell me something, and I was quite religious about them.

"I used to absolutely drop everything and follow that course of action, so I didn't pull them out lightly because I knew it could mean jettisoning whatever I was doing at the time to do something completely bizarre, like take a long walk or something - the last thing you want to do if you're panicking about not doing anything that day."

Eno also warns in the same interview that your chosen random strategy might not always appear to offer the correct solution at the time. The track Spirits Drifting on Another Green World was shaped by an Oblique Strategy… eventually, anyway.

"When I started making that piece I was really at the end of my tether. I'd been working on it for the whole day; we had almost nothing on tape and it sounded like a piece of crap. I was standing at the synthesizer crying as I was playing it because I thought 'I don't know what I'm doing'

"I took out an Oblique Strategy and it said 'Just carry on'. And I pissed myself laughing because it was such a low level answer to what I was expecting. So I just carried on. In the next half hour or so that piece suddenly gelled into something, and in fact it gelled into something that I still like very much."

Eno wasn't by any means the first composer to dabble in randomly generated processes for composition. His strategies could also be seen to be loosely based on the ancient Chinese text, I-Ching, which is a similar 'decision helping' set of 64 ideas, and one used by avant-garde composer John Cage. Even Mozart employed Musikalisches Würfelspiel, a random dice idea to put pieces of music together.

However, Eno's cards are more aimed at music producers so still hold relevance even today. And there's a great school of thought that you can generate your own Oblique Strategies, depending on the kind of music you make. 'Go bassier', 'Duck off', that kind of thing.

You could even create a set for life. Got relationship issues? Try 'don't argue', 'discuss it now', or (more likely) 'just do as you're told'.

You could even create a set for life. Got relationship issues? Try 'don't argue', 'discuss it now', or (more likely) 'just do as you're told'.

Whatever, if you ever get stuck for ideas in the studio, and we all do, have a dabble with some Oblique Eno. You wouldn't be the only music producer to have used them as, over the years, everyone from Bowie (with Eno on the Berlin trilogy) to Coldplay (on the album Viva la Vida) have employed them.

You can purchase a set of cards via the Eno Shop website should you wish – paying £50 for the privilege, but very much buying from the horse's mouth. There's also a cheaper iPhone app, or simply visit a website like this to randomly generate a strategy for you to use.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.

“I’d be running from the studio to other speakers in the house, basically going insane trying to get mixes to sound correct”: Ezra Collective’s Joe Armon-Jones on why he created his Aquarii Studios and his dub-influenced mixing technique

“I haven’t been able to see the performance, but I have enjoyed it”: Elton John tells audience at Devil Wears Prada premiere that he’s lost his sight