What actually is reverb and how does it work?

It’s an essential effect used on almost every track, but how does it work its magic?

Even the smallest space will create some kind of reverberation that will be perceived by the listener. This reverb is produced by any sound in a space being reflected from available surfaces back to the listener. Even the interior of a car will produce internal reflections. Of course, larger spaces and more reflective materials will result in much larger reverbs.

There are only subtle differences between the aural phenomena known in music production terms as reverb and delay, which can lead to confusion. Delay essentially mimics an echo, the effect caused when a sound bounces back off the listener’s physical surroundings, giving the impression of a repetition of the original sound. When multiple echoes arrive at the listener in such close succession that they become indistinguishable from each other, we call this a reverberation.

Reverb comes in three distinct phases. The first is the original sound, sometimes known as the impulse. The second phase is known as the ‘early reflections’ phase, the first of the echoes reaching the listener, as they subconsciously judge the size of the space.

Early reflections are more easily distinguishable from each other than the reverberation itself, which makes up the third phase, characterised by multiple, overlapping echoes. Reverbs gradually decay, with the total reverberation time determined by a variety of factors, including the materials and hardness of the walls, the overall shape of the space and what other objects are in it.

In the early days, reverb was produced by simply recording in a specific space; this was the only surefire way to get the sound you wanted. In the ’40s, both plate and spring reverbs were developed, allowing sound engineers to recreate spaces artificially for the first time. This literally transformed the sound of music production – pretty much every mix created from this point contained some sort of reverb processor, adding space and dimension to records of the time.

Early reverbs were large, cumbersome and required serious hardware to operate. Even with the introduction of rack-mounted digital processors, pro reverbs required substantial investment. Now we’re lucky enough to have access to all of these reverb creation methods in the form of digital emulations. This gives us the flexibility to mix different spaces and create real contrast.

Let's run through several different types of reverb and how they're created.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Convolution

Convolution reverbs use a recording of an actual space called an impulse response. This initial recording is often taken using a test tone or click as the source. The resulting recording (and some clever maths) is then used to create a realistic reverb. It has been argued that these reverbs are some of the most realistic there are and they have even convinced listeners they are in the actual space being mimicked.

These reverbs often inflict a lower CPU load than traditional effects but do take up a lot of disc space. They can also be quite expensive due to the amount of development involved. Convolution reverbs are probably best if you are looking for absolute realism and a lower CPU load.

Algorithmic

Algorithmic reverbs are the mainstay of studio tech. The majority of plugins and digital hardware that create reverb effects use this sound creation method. Essentially what we have here is a CPU crunching numbers and code to create an approximation of a realistic space.

Mileage here will vary as some companies (Lexicon, TC Electronic, UVI, Sonnox etc) have absolutely mastered the art of writing algorithms, while other offerings may not be so stellar. The real plus point here is that the plugins contain no samples, so are small in size. Often if the algorithms are well optimised, CPU usage can also be modest.

Algorithmic reverbs are best for everyday use as they are pretty much commonplace in most DAWs. They are easily installed and can produce pretty much any form of reverb.

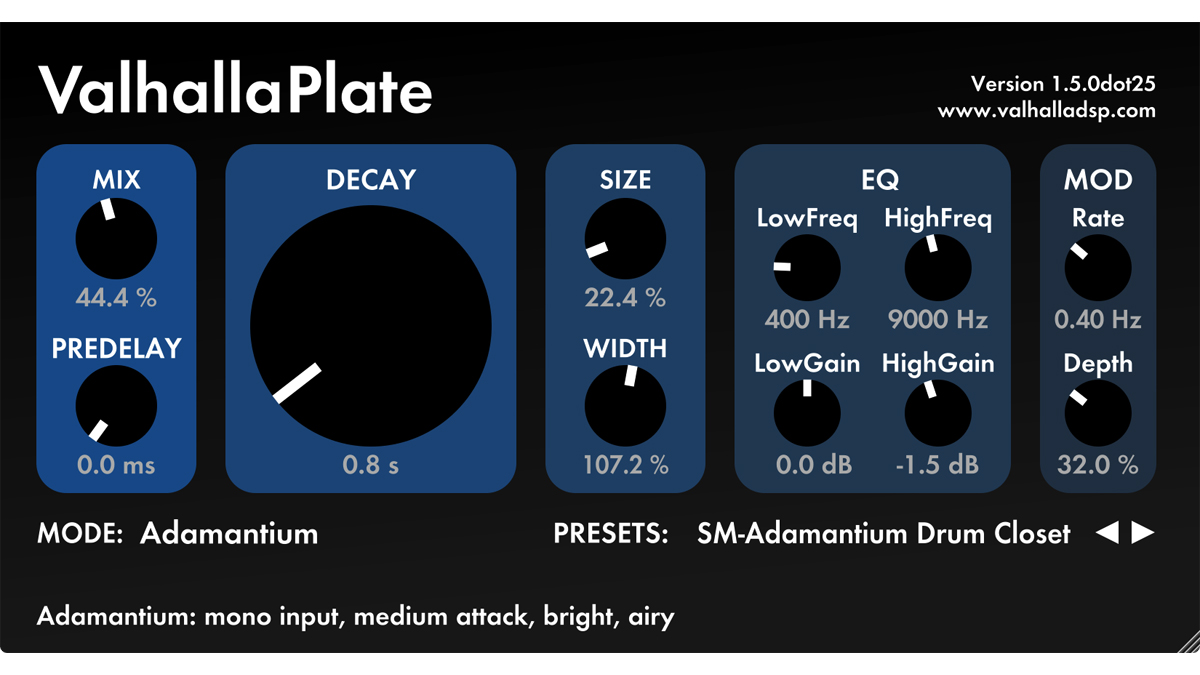

Plate

Plate reverb has some similarities to spring reverb in that it uses a mechanical apparatus to produce the reverberation effect. Large metal plates are hung in narrow spaces, audio is then fed into the space and the resulting reverb is captured at an output stage. For plate reverbs to work well, large amounts of space are needed but the sound created can be stunning.

Although the real thing can only be found in truly pro installations, some excellent software recreations are out there now. Good plate reverb emulations can sound stunning and work very well with just about anything but are most famous for their use with vocals and organic instruments such as piano and guitar.

Spring

Spring reverbs were the first hardware reverbs and used an actual physical spring in a cabinet to create the illusion of a physical space. Though this is now far from the most realistic form of reverb, it has tons of character and is still used in many studios.

It has a simultaneously metallic and analogue quality and is widely used for guitar, vocals and synth processing. There are some awesome spring emulations out there and you’ll still even find working spring reverbs housed within some guitar amps.

Recording a real space

The most realistic way to create a space is to record one! To do this, you either have to go to the space and record the sound you want in your mix or send something from your mix (in real time) to a set of speakers that plays back in a space and in turn is recorded. This may sound pretty complex but it’s actually the way it’s done in many studios.

Dedicated, or unused rooms can be used just for this purpose. A set of speakers will be placed in the required space and a pair of high-quality stereo mics will pick up the resulting reverberation. This can then be fed back into the mix – you’re essentially using the room as a very large effects unit.

Recording real spaces is the ultimate way to create your reverb effect. It’s as real as it gets, but it will require some legwork and high-quality kit.

I'm the Managing Editor of Music Technology at MusicRadar and former Editor-in-Chief of Future Music, Computer Music and Electronic Musician. I've been messing around with music tech in various forms for over two decades. I've also spent the last 10 years forgetting how to play guitar. Find me in the chillout room at raves complaining that it's past my bedtime.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

MusicRadar deals of the week: Enjoy a mind-blowing $600 off a full-fat Gibson Les Paul, £500 off Kirk Hammett's Epiphone Greeny, and so much more