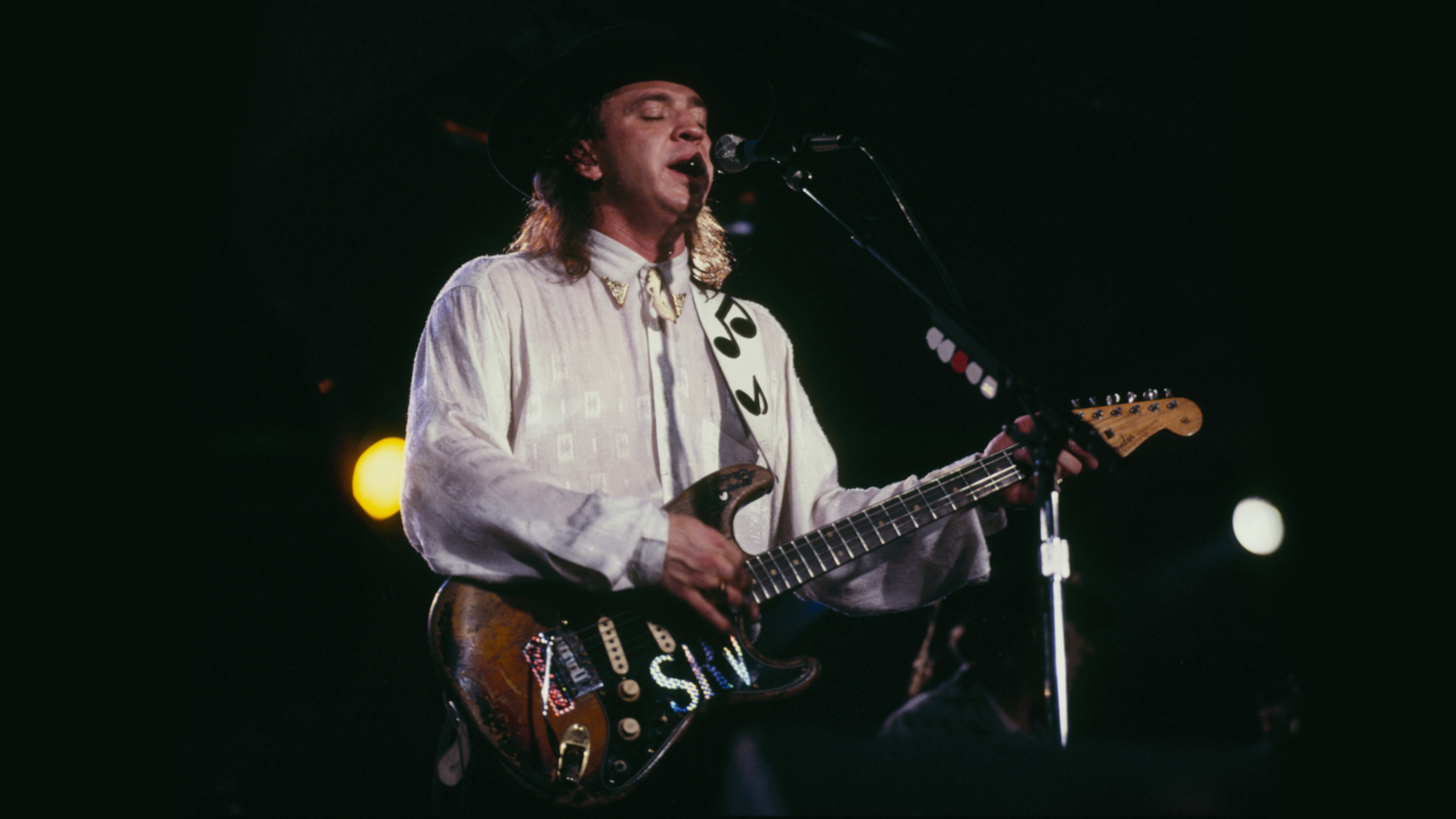

"Stevie liked a clean sound. He really didn't turn everything up until the last song": Stevie Ray Vaughan's tech Rene Martinez remembers his boss, friend and blues guitar legend

When Stevie Ray Vaughan was looking for a guitar tech, he knew just the man: Rene Martinez. He was an old acquaintance, a well-known luthier and repairman at Charley's Guitar Shop in Dallas. Stevie's brother Jimmie was a customer, and eventually Stevie started dropping by the store.

Martinez, a classical and flamenco guitarist who got his start in the repair business painting cars and refinishing violins, was initially hesitant about going on the road with Vaughan. And the way that the guitarist treated some of his instruments on stage - slamming them against walls, dragging them across the floor by the tremolo arm, standing on top of them - might have played into his reticence.

But Martinez was charmed by Vaughan, dazzled by his talent and won over by his persistence - Stevie kept calling until Rene said yes. It wasn't always an easy gig, though: Vaughan didn't bring an arsenal of axes on the road; in fact, he toured with a prized but small selection of Fender Stratocasters that included the famed 'Number One,' its sidekick called 'Lenny,' another called 'Butter,' one called 'Red,' and a Frankenstein model called 'Charley.' (The latter wasn't a true Stratocaster; it was assembled from spare parts by Charley Wirz, owner of Charley's Guitar Shop.) This meant that the touring life for Martinez was one in which he was "always in repair mode" at every show.

Rene Martinez was Stevie Ray Vaughan's guitar tech from 1985 until the beloved bluesman's death in 1990 and here in MusicRadar's 2010 interview he remembers the man who would become a friend.

What was the first guitar Stevie brought in to you, the Number One Strat?

"Yes, indeed. It was the Number One Fender Stratocaster. The action on it was pretty high. The guitar was pretty beat up, even then, showing a lot of wear and tear. He had had somebody install a left-handed tremolo system, even though he was a right-handed player."

Because he wanted to emulate Jimi Hendrix?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I would imagine that was the case. I never really asked him. But that's what he had done. Maybe he liked the way it moved."

Number One was a '62 Strat, but Stevie was fond of calling it a 1959 model.

"That's right. The reason why he called it a '59 was because of some wiring in it - the back of the pickups said '1959.' So the pickups were a '59, but the body of the guitar was a '62. My attitude was, 'Hey, it's your guitar, you can call it whatever you want.'" [laughs]

I know you did a lot of repairs to the neck of Number One…

"The term 'repair' can mean a lot of things. I refretted it and I put in a bone nut, or an ivory nut. I joined Steve in 1985 and I refretted the guitar maybe once a year, and I replaced the ivory nut probably as many times. You can't use the same nut once you refret the guitar - the action would be too low.

"The last time I refretted it, I told him it would be the last time. He asked me why and I told him that I had to plane to fingerboard every time I put new frets in. He would really dig in; he not only wore the frets out, but he would wear out some of the wood, as well.

I used to adjust the screws down at the bridge to raise the height, and I would run out of thread - I couldn't make the strings any higher

"After a while, the fingerboard was getting thin and I told him I'd have to put a new one on. We decided to replace the neck and keep the original until I had time to made that repair. But I never got a chance to do that, so the neck that is back on Number One is all original."

You used to put jumbo-sized frets on the guitar, right?

"Yes. He used to use medium-sized frets, but he'd wear them out, so I said, 'You're probably better off with jumbos.' That way, I could work with them through the year, reshape them so he could continue to play. He enjoyed them - they gave him more access to sliding up and down."

Did he use heavy gauge strings?

"He did. He started with a .013 and ended with a .060. They were big, yes, but that wasn't the only thing; it was the action, the height of the strings. I used to adjust the screws down at the bridge to raise the height, and I would run out of thread - I couldn't make the strings any higher."

A lot of this runs counter to the way many guitarists like their instruments set up, particularly players who favor bending strings. Most players would ask for slinky strings and for their action to be set low.

"Yeah, well, it's just the way he liked to get his tone. He had very strong hands; the way he attacked the guitar, it all came from his hands. Plus, he had his guitar tuned to E-flat, which compensated for other variables. I asked him about it once and he just said, 'I can't sing in E; it's gotta be in E-flat.'

"Even so, the guitar was hard to play, and he would literally be drawing blood from the tips of his fingers. I saw some blood on the guitar one day and I said, 'Hey, are you OK?' And he said, 'Aw, my tips are starting to get cut, you know.'

"I told him that we could get the same tone by setting his guitar up differently and using some different things. Once we started experimenting, he was pretty happy. He looked at me and said, 'How do you think up these things?' And I just said, 'Well, I'm your guitar tech. That's what I do.'"

What was the main difference between Number One and the Stratocaster known as 'Lenny'?

"Lenny was given to Stevie by Lenny [Lenora Bailey, Stevie Ray's wife from 1979 to 1988] and some friends. It was a different color [brownish-orange] and it had a maple neck. He used it on a lot of different songs, but I especially remember him using it on the recording of Riviera Paradise. It was a special guitar because it could scream and chime. Different guitars have different tones, and this one seemed to really work for that song.

"What he would do is, he could strike the strings near the tuning machines, then he would use the tremolo arm to make a kind of weeping sound. Lenny seemed to make this sound the best for him."

Somewhat ominously, there was an accident in New Jersey during a show, just a few weeks before Stevie's death, that almost destroyed Number One.

"We were doing a co-headlining tour with Joe Cocker. For that show at the Garden State Arts Center, we were on first. The venue had these acoustic baffles for when orchestras would play, and they were monsters, maybe 20 or 30 feet tall and six or eight feet wide.

The first guitar I checked on was Number One. Well, the neck had been broken; it looked like a Steinberger… the headstock was basically dangling

"They were all leaning against the wall and they were tied up, and at the end of the show, as we were changing sets for Joe Cocker, the stagehands were pulling the curtains and one of these huge baffles came crashing down on my workstation, where the guitars were set up.

"The guitars were basically holding the baffle up. It took a bunch of us to lift the thing off the guitars, and of course, the first guitar I checked on was Number One. Well, the neck had been broken; it looked like a Steinberger… the headstock was basically dangling.

"Stevie came out to see what had happened, and I was just lost for words - I didn't know what to say. Later, he went to his dressing room, and I went to see him. He gave me this big old hug. 'You could have been killed!' he said - because I was standing pretty close the guitars when the piece of staging came down. He forgot all about his guitar and thought about Rene. [laughs]

"Word traveled fast. I got on the phone to Fender, and they wanted to know where to send a replacement neck."

And Stevie was OK with using a replacement neck?

"Oh yeah. The neck that was broken wasn't the original Number One neck - I had put that aside to eventually fix, although I never got the time to do that before he died."

But after Stevie died, you put the original from Number One back on the guitar. [Number One is now in the possession of Jimmie Vaughan.]

"That's right."

The Dumble was powerful and clean, and he liked that; the Marshall was big and warm; and then the Fenders delivered true, clean hi-fidelity sound

What were some other elements of Stevie Ray's sound? What kind of amps and effects did he use?

"We used four pedals: a CryBaby wah-wah, an Ibanez Tube Screamer, an Octavia and a Dallas Arbitar Fuzz Face. Amp-wise, there were so many combinations we went through. When I first started working with him, it was a Dumble Steel String Singer and a 200-watt Marshall head, and each one of those amps was playing through EV-loaded Dumble 4 x 12 cabinets - one was angled and one was flat.

"We also had two black-face, EV-loaded Super Reverbs. In addition, we used an EV-loaded Fender Vibroverb, and it powered the Fender Vibratone Leslie speaker.

"Stevie liked a clean sound. He really didn't turn everything up until the last song. But in the meantime, throughout the show, it was a clean, beautiful sound, with a little reverb to make it wet.

"The way he had it configured was so that everything acted like one big gigantic speaker. The Dumble was powerful and clean, and he liked that; the Marshall was big and warm; and then the Fenders delivered true, clean hi-fidelity sounds. They all sounded great together. It was beautiful, just gorgeous."

What was he liked to work with? His drug and alcohol problems are well documented, but after he got clean, did he change at all?

"He was always the same to work with. When he got cleaned up, you know, his playing got better. It's like with anybody who's had a couple of drinks in 'em - they sing the way they do and they play the way they do. It was never a bad thing. One day, however, he decided he didn't want to do any of those things anymore. But he was always Stevie Ray Vaughan to me.

"We enjoyed each other's company a lot. We were in it for the duration of our lives. If we didn't get along on a particular day, it was because I was having a tough day or he was having a tough day."

I lost a very special friend

The last show at Alpine Valley…What are your memories of hearing the news that Stevie had died?

"It was a strange night for me after the show was over. I didn't know what to think. And then, of course, once I got back to the hotel and I got a phone call at about six in the morning telling me that Stevie had died in a helicopter crash, I just couldn't believe what was going on.

"I couldn't cry or anything because I just couldn't believe what was going on, until later…later it hit me. I lost a very special friend."

Of all the blues players who are our there now, have you heard anybody who is Stevie Ray's heir apparent?

"You mean somebody who can take his place? Because nobody ever can, and nobody ever will. But there are people who play like they do, and why they play like they do is because of who they grew up with. You can hear a person who plays the blues a la BB King or Albert King. And if they're good enough to play, then they're good enough to copy, to emulate. But hopefully, you put in your own juices and it all becomes you."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge