"It’s just going to get better over the next few years until everyone’s going to be wearing them": How VR and AR could change music production

We’re intrigued by the latest glut of augmented and virtual reality headset releases from the likes of Apple and Meta. Our question: how good are they from a music-making POV?

For many, the appeal of VR headsets might be considered to be the exclusive domain of gamers, with little else to justify the (sometimes intimidating) pricetags.

There’s also the embarrassment factor that keeps the more self-conscious among us from being seen wearing a chunky headset. But, with the release of Apple’s Vision Pro, a more holistic vision of the VR/AR headset was presented, positioning it not for techies, but as a workflow-assisting, reality-distorting, focus-honing productivity tool.

For music-makers – where productivity and immersion are key – the renewed focus on the potential of VR is incredibly exciting. VR gives you complete control of your visual workspace, and it’s possible to save that setting, and recall it – no matter where you are.

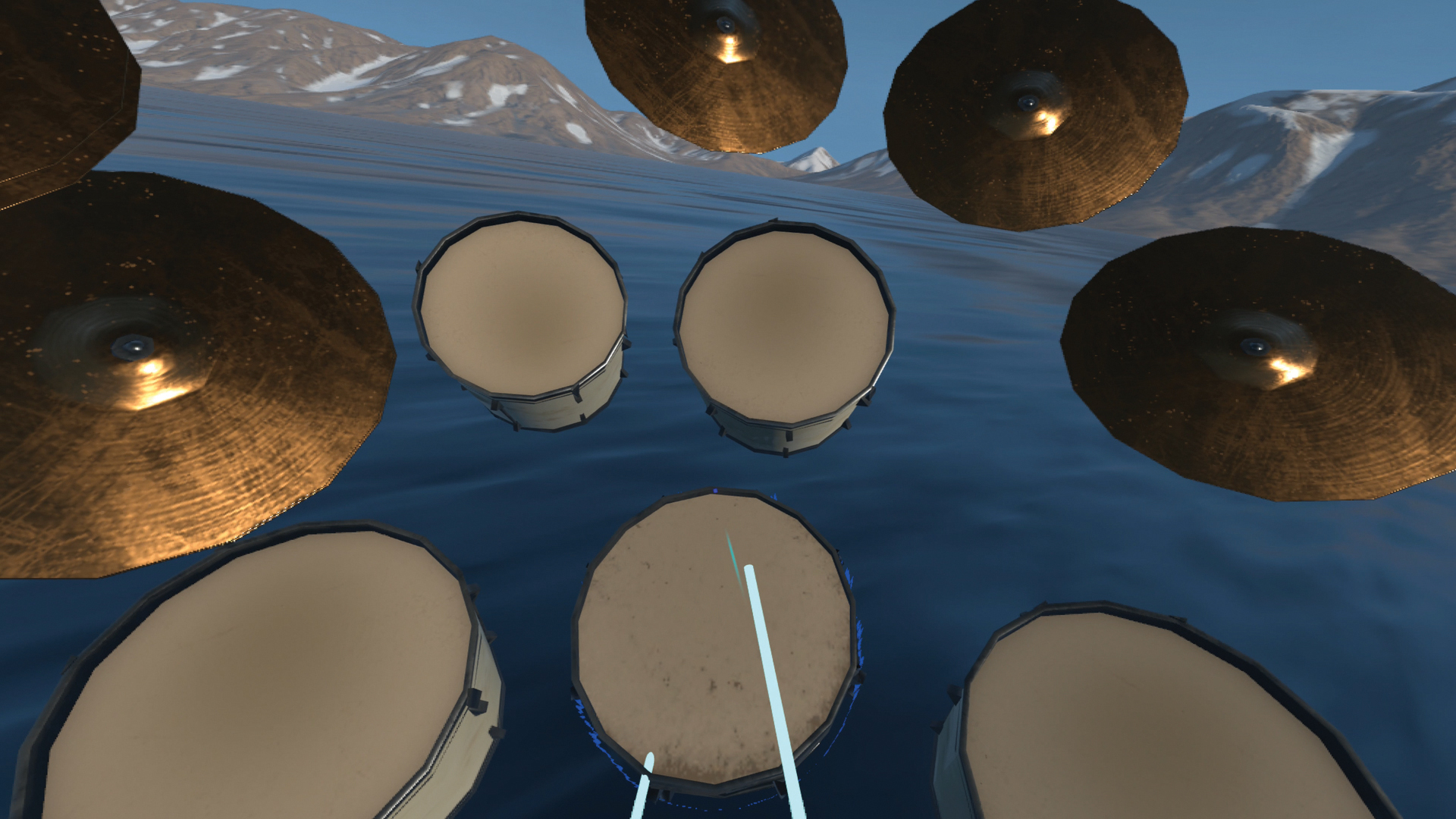

Then there’s the chance to use enormous virtual displays, bigger than you could probably fit into your real-life workspace. Coupled this with the ability to ‘touch’ virtual instruments without a controller in-between and a new way of thinking about music production presents itself. This radical transformation of interface and environment could get you creating previously unimaginable types of track.

The tools: Apple vs Meta

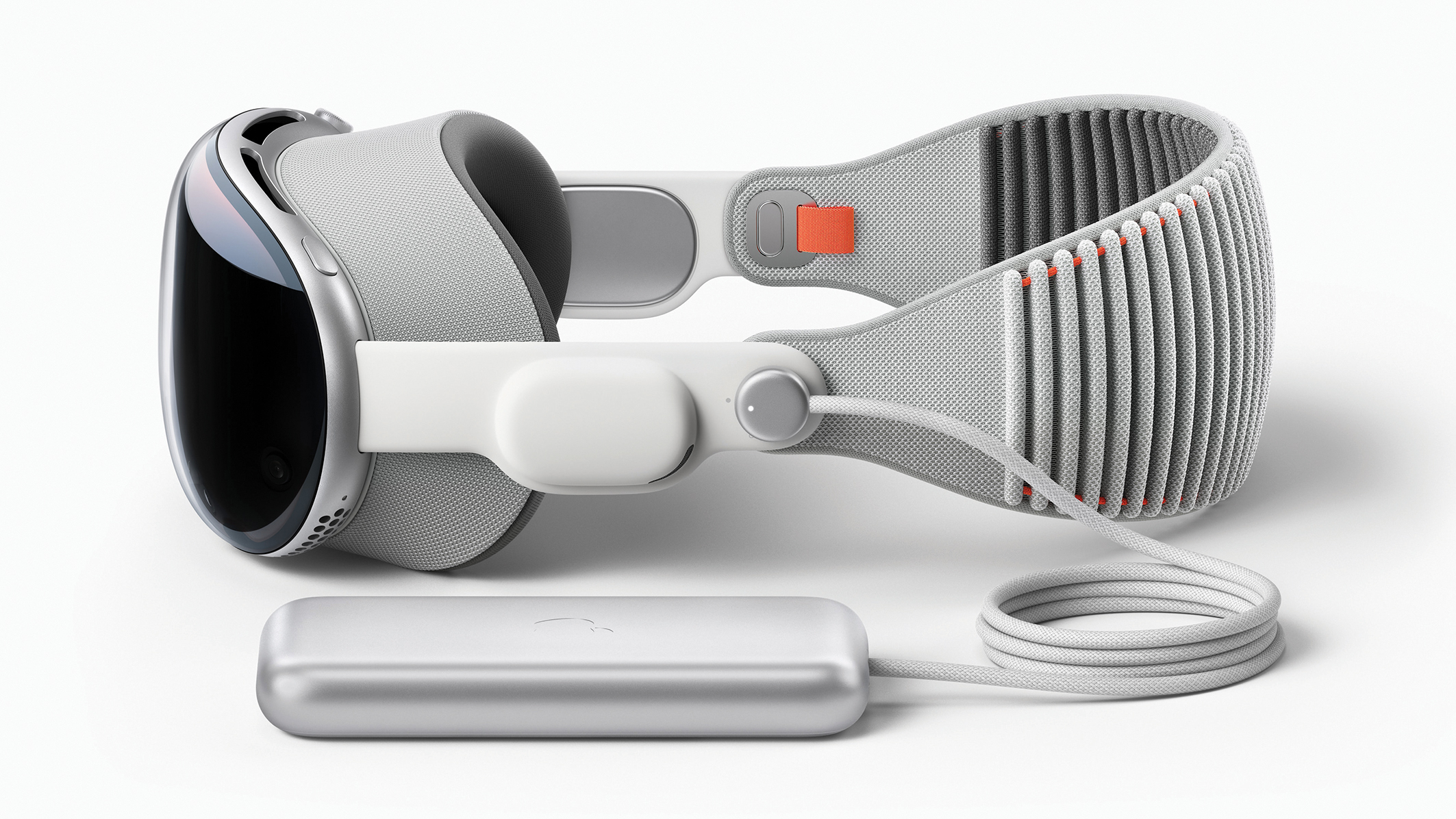

So how do we explore this fertile ground? Since 2019, the dominant mainstream VR option has been Meta’s Quest, the current model being the Quest 3 (£479.99 – meta.com), while in February, Apple released the Vision Pro ($3,499 – apple.com). Both of these are primarily seen as consumer devices, but it’s very possible to create and perform music on the Quest and Vision Pro today. We’ll take a look at some of the specific software shortly.

How you choose between these devices is a matter of budget and taste. The Quest 3 uses an Android-based operating system, and includes two Touch Plus controllers to provide haptic feedback. It’s been around since 2019, so by this point has a decent and diverse app library. Critically, the pass-through quality could be better, and it’s skewed towards Windows compatibility. Apple’s Vision Pro uses visionOS, and no controllers are needed for day-to-day use. It boasts superior image quality, and is compatible with many iPad and iPhone apps, so there’s more than enough to get you started.

It is, however, limited by the usual closed Apple system. The Vision Pro isn’t even marketed as a full VR solution, but we can imagine how that could change before too long.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Wearing a headset when you’re working solo is one thing – it’s another to integrate it with studio gear

Wearing a headset when you’re working solo is one thing – it’s another to integrate it with studio gear. It’s pretty fundamental to be able to get your music in and out, right? The Quest 3 makes some of this straightforward, with a 3.5mm headphone jack, and file-sharing over WiFi, USB drives, or a USB-C cable to your computer, and it supports USB-C audio.

The Vision Pro, being an Apple product, has no physical connectivity to speak of at all, relying on the usual Apple cloud/web-based methods for file exchange, and depending on Apple’s low-latency H2 wireless connection for audio output. The Quest 3 and Vision Pro both support avatars, which, along with passthrough, can make the virtual experience feel less isolated. The Vision Pro has its own ‘Eyesight’ feature and Persona avatars to build on this, while the Quest uses Meta avatars, and some apps support the Ready Player Me service.

AR and VR explained

The term ‘Virtual Reality’ was originated by Jaron Lanier, a former Atari employee who went on to found VPL Research, one of the first companies to sell VR hardware (including the groovy VPL DataSuit). When wearing a VR headset, the user is fully immersed in a digital environment, which they can explore either through physical movement, or gestures and controllers. Cameras on the headset are used to capture info about the world around the user.

Roland's new augmented reality service lets you place a grand piano in your bathroom

Then there’s AR – augmented reality – where through those same cameras, a headset allows the wearer to see what’s going on around them in the real world, with digital objects superimposed on that. This is referred to as ‘passthrough’, and can be used for aesthetic or practical reasons. Great value is placed on how clearly passthrough shows the outside world. The Quest 3 is Meta’s first headset with full-colour passthrough while the Vision Pro delivers very high quality passthrough and image resolution – one reason it’s so expensive.

Passthrough quality is also affected by ambient light available, like most cameras. We’ve found the Quest 3 passthrough is a good fit for AR use, brilliant for moving around, but not ideal for tasks like reading text during long work sessions, like in a web browser. For music use, we’ve relished the full immersion of VR in a solo setting, but we’ve come to think of passthrough as an essential when working with other people or interacting with real-world equipment and situations.

The app-makers

One of the clearest implementations of a Vision Pro DAW comes via RipX DAW Pro from Hit’n’Mix. Founder Martin Dawe explains how the company landed in the VR space: “We were doing stem separation and audio editing, using our special ‘Rip’ audio format. It stores all the parts that you need to make waveforms; it’s a bit like MIDI, except it contains all the pitches and in-depth information like the timbre, phase level and panning.

“This means you can do whatever you want with this audio. It’s always been in my mind that it would be best used on a kind of three dimensional interface, because you have the layers of the different instruments, which get hidden a bit on the 2D screen.”

Martin’s a great believer in the Vision Pro. “At the moment, the Quest seems more like a gaming device, while Apple seems keen to make the Vision Pro a true computing product – the passthrough is really good, for example. I made some other music products, and the Apple versions outsold the Android stuff tenfold. I’m impressed with the Vision Pro. It’s just going to get better, without a doubt, over the next few years until everyone’s going to be wearing them, and the price is actually not bad.”

Dawe is also relatively unconcerned by the Vision Pro’s lack of connectivity. “I believe we are looking at an ultra-low latency wireless future and I suspect Apple will put a great deal of energy into making sure this works well.”

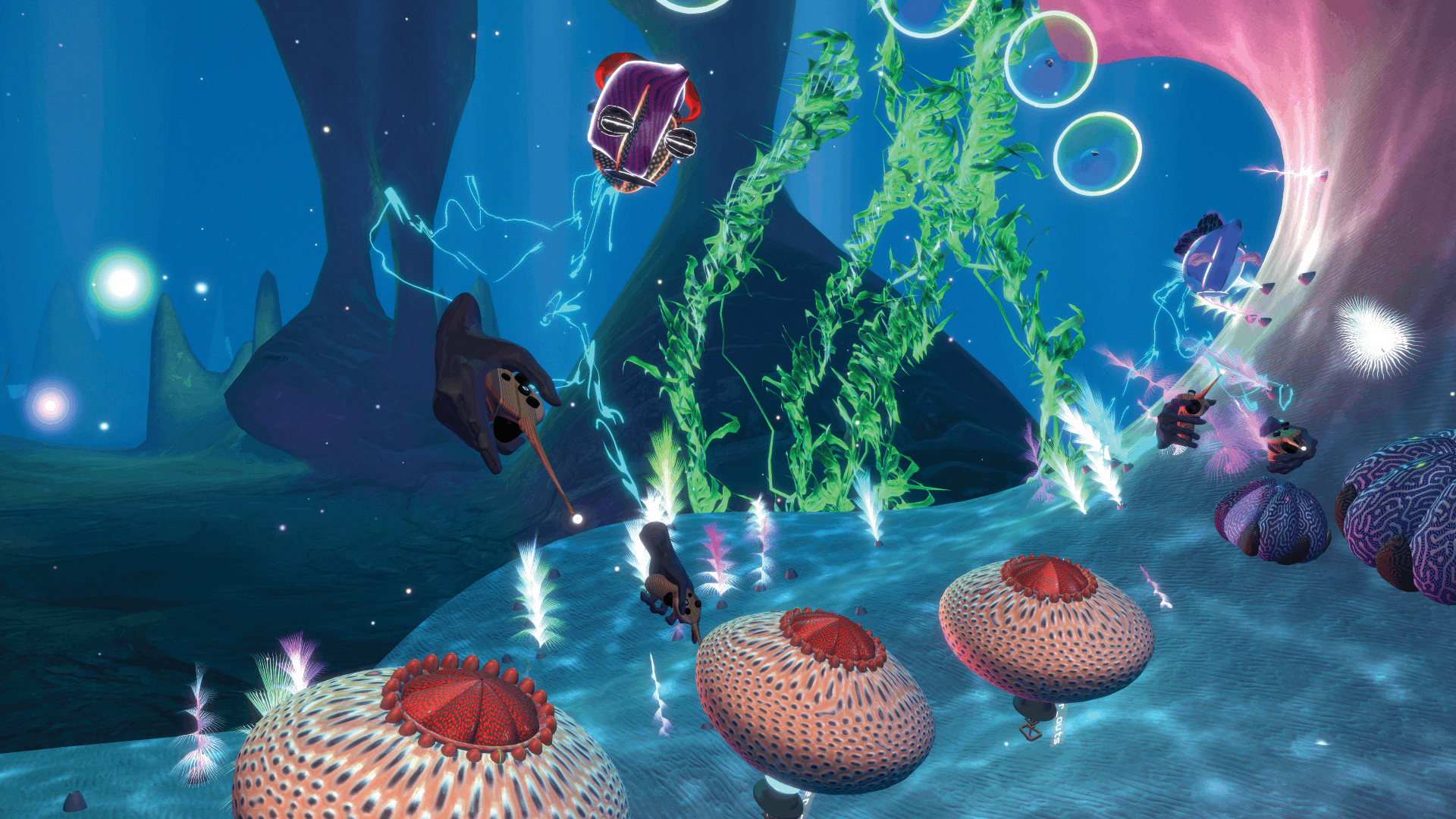

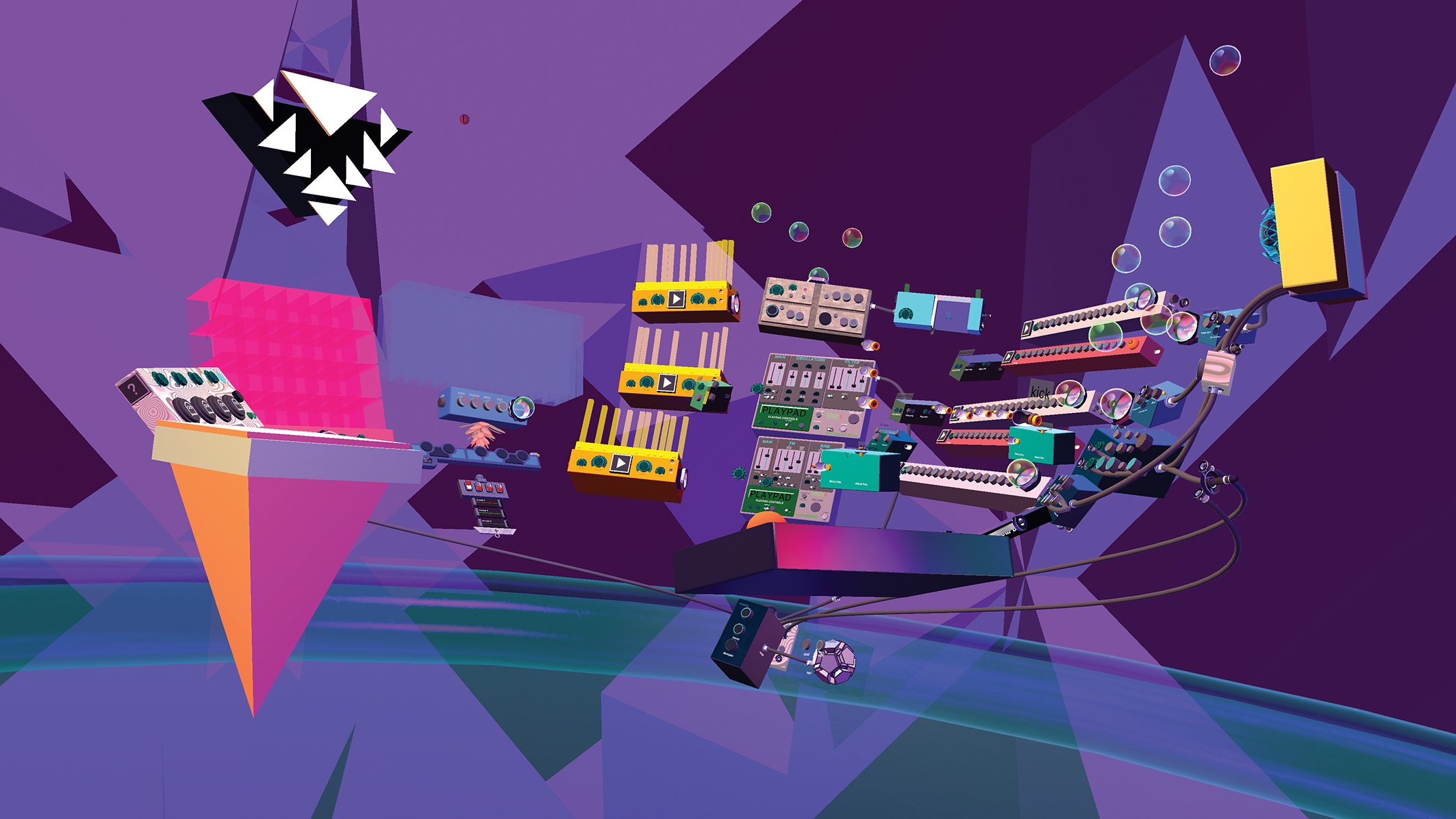

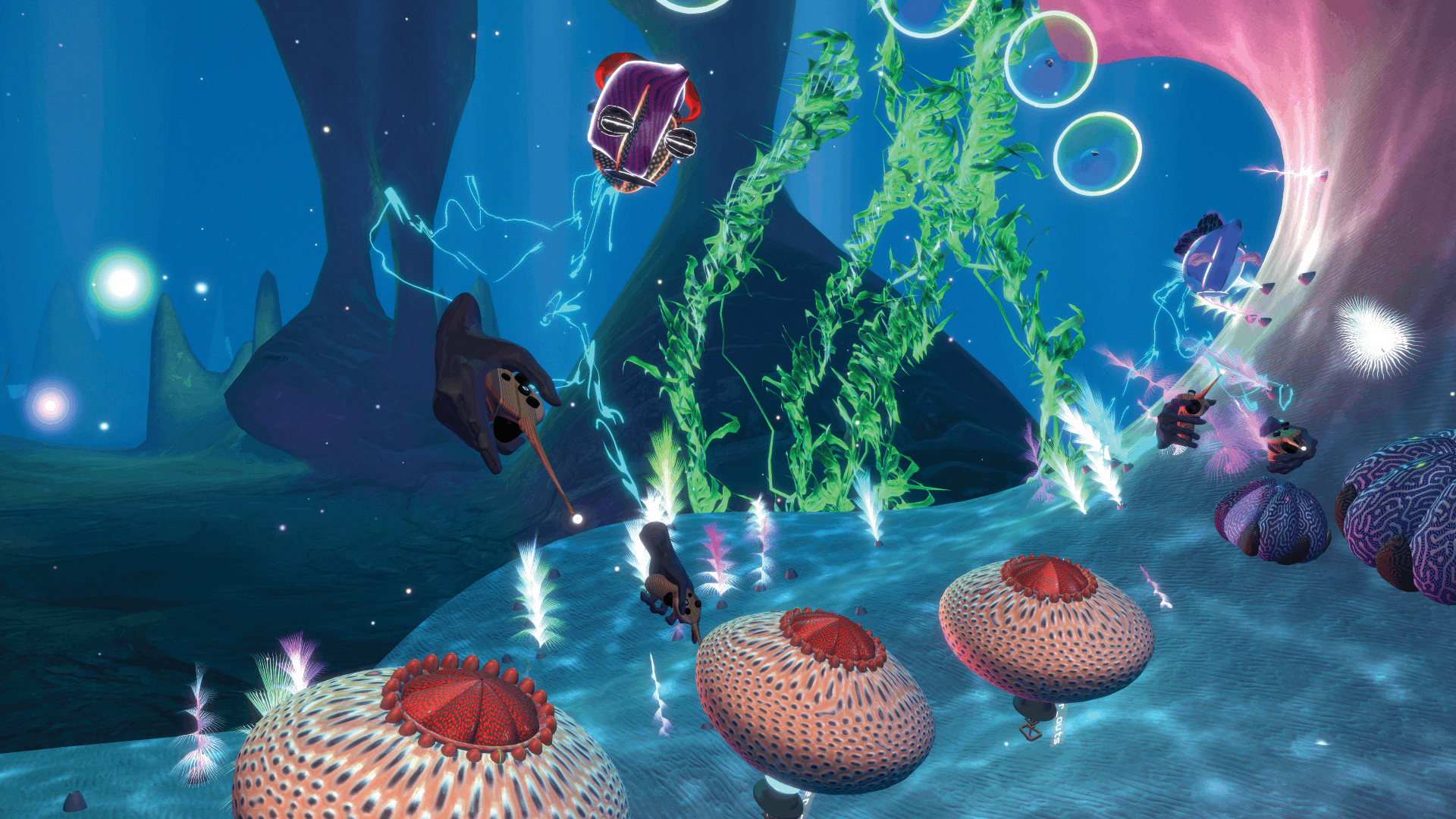

As far as we’re concerned, PatchWorld (£22.99 – patchxr.com) is the most exciting VR music app on the market, containing everything you need to create music and visuals for a full A/V set. We strongly recommend PatchWorld’s interactive tutorials, as they’re like no tutorials you’ve ever seen, guided by some very eccentric and engaging animated characters.

PatchWorld provides total control over all aspects of the environment; a background can be a sky, texture, solid colour, or simple passthrough. There’s also a library of music devices, including sequencers, synths, mixers, samplers (including the very weird Blooper), and effects, right up to a bizarre collection of sound-making objects, such as a beer bottle, a sausage, and a skull.

Signing up to the PatchWorld Discord gets you access to the latest beta, and to ‘Blocks’, which are core elements that can be used to build devices from scratch, including routing tools, oscillators, virtual strings, and effect elements, objects being linked by dragging virtual cables, Reason-style. Satisfyingly, any element can be placed anywhere in the 360º space. There’s also a library of visual effects, and the giddy thrill of being able to import your own 2D and 3D images.

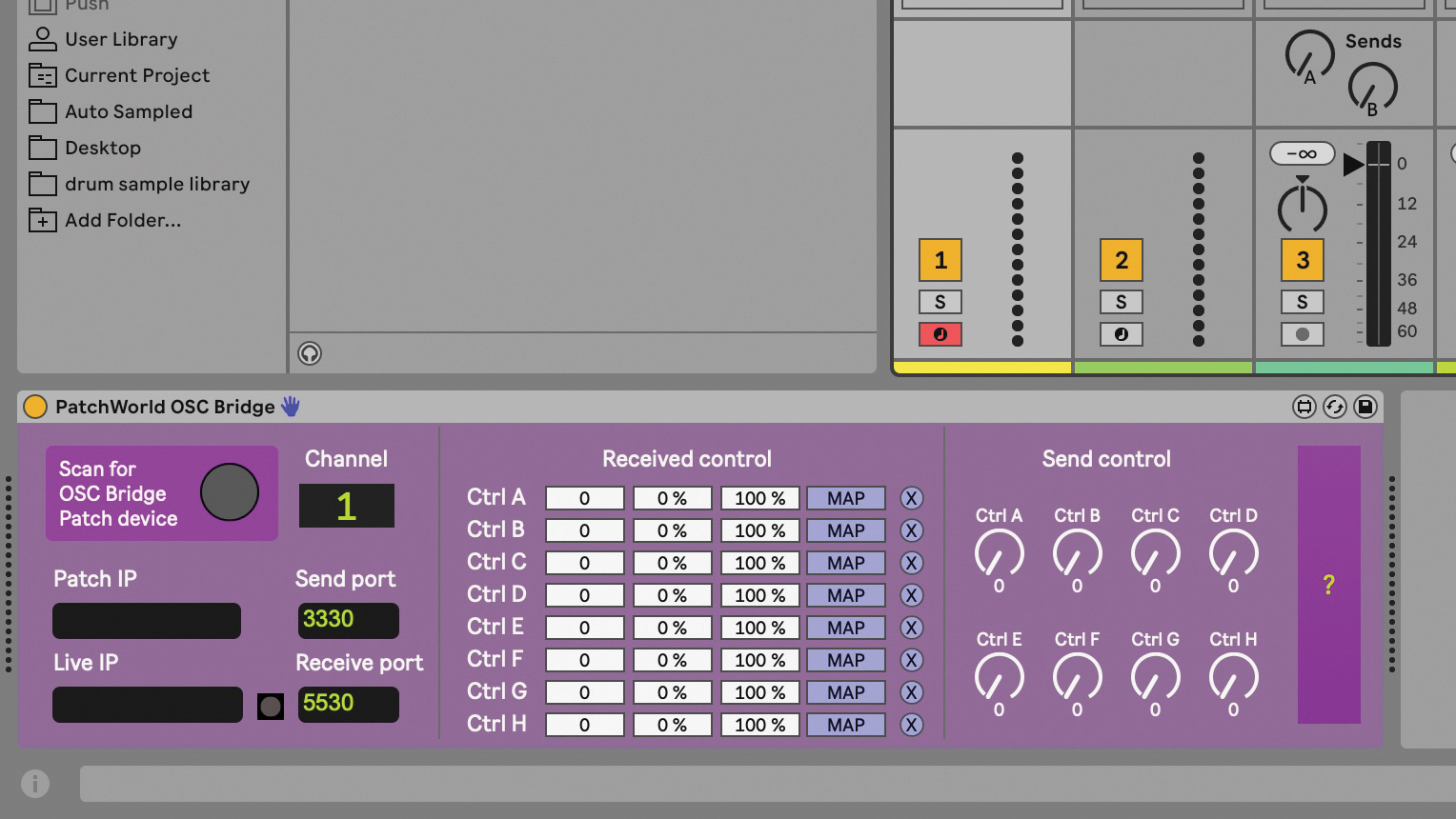

For those who want to create a hybrid system with headset, computer, and music hardware, PatchWorld includes Ableton Link and wireless MIDI control, via a collection of control interfaces, and the Max For Live PatchWorld OSC Bridge device. In our exploration of it, importing or recording samples was straightforward enough, but there was some head-scratching involved when it came to capturing the spatial performance audio inside the app. It seems that it’s currently depending on the audio outputs, or using the Quest system’s movie capture capability.

We spoke to Gad Hinkis, PatchWorld’s product manager, and asked him to give us the elevator pitch for the benefits of PatchWorld. “PatchWorld is an app where a 10 year-old can put on a headset and just start jamming. They don’t need any musical experience, because we have all these playable instruments, like you can play drums on a bubble, or you can record your own voice and put it inside of underwater creatures.

“But under the surface, if you want to go deep, this is actually a professional-grade content creation system. Right now for us, it doesn’t make sense to invest the resources in the Vision Pro, but long term, obviously we’re going to be there. And this year we’re going to add better hand tracking, so you don’t need the controllers for playing.“

Gad tells us that while it’s currently a VR-exclusive app, PatchWorld is heading to conventional desktops too. “The next thing we’re going to do, hopefully, is to make it easier for people to access the app outside of VR,” Gad explains. “We are very close to releasing the beta of a desktop app that you can download on your Mac and PC. You can navigate worlds and join multiplayer sessions.”

“Having a full-body music experience is very important because with electronic music until now, we were stuck in the age of tweaking dials and sliders and buttons. But actually, humans for 100,000 years have been moving their body around to create music. And with multiplayer, you can have an electronic jam session and a wall of synthesisers, and playful instruments.”

Jim Simons of Alive In Tech is an innovative developer who’s aiming to transport the fun and excitement of the controllerist mindset into virtual reality via his Tranzient app. “We want to [bring] the ‘Ableton Push’ workflow to VR. I’ve tried the Vision Pro, and I’ve used Quest 2 and Quest 3 a lot.

“You’d definitely describe it as premium hardware, passthrough is really good, and the visuals are, like, 50% better than a Quest 3. As [the Vision Pro] is so expensive, I’m not going to support it now, although absolutely we will in the future. Also, my applications are Unreal Engine based, which is very beta at the moment in terms of Vision Pro support.”

The latest update to Tranzient includes hand tracking and passthrough. “I’m trying to get ahead of the curve in how people are going to use the Vision Pro,” says Jim. “I actually spent a couple of years working for Ultraleap, who are the hand tracking experts behind Leap Motion, so I gained a load of hand tracking skills.

“Probably what I’ll do next is create something with an easier learning curve. If you understand Ableton, Tranzient is kind of easy, but if you don’t understand Ableton, it’s not. My Ableton controller project, AliveInVR, pretty much stopped development two years ago; there’s just not enough people with VR who are also using Live on a PC.”

Jim sees the Quest and Vision Pro co-existing more harmoniously into the future. “There’ll always be a parallel development between the Quest and Vision Pro, I think, especially as Apple have gone high end.”

Peripheral vision

VR’s peripherals and app ecosystem may feel like a little bit of a financial black hole but if you’re invested in this universe, they will just add to the fun. Take the humble USB C cable. Dull, but it’s vital if you want to use your swanky new headset while charging, without feeling like you have to keep your head slightly inclined towards the charger for fear it’ll pull out. A couple of metres are therefore recommended (there are also head straps available that include built-in batteries to boost beyond the typical two hour-ish time limit).

Although the Meta Quest and the Apple Vision Pro have good onboard speakers, sooner or later you’ll need headphones that fit comfortably over the headset, and we’ve had great success with the Final Audio VR3000 in-ear phones, which are optimised for surround. On the visual side, Google’s Chromecast 4K, with its HDMI connection, has worked well in terms of sending audio and video wirelessly to TVs and video projectors.

When we come to music apps, the Quest has been around longer, so unsurprisingly, it has an edge, for example MoveMusic ($49.99 – movemusic.com), should appeal to controllerists, wirelessly controlling music software on Mac or PC.

Early adopters for the Vision Pro include Moog’s Animoog Galaxy ($29.99, moogmusic.com), a VR version of their much-loved Animoog synth for macOS and iOS, and Algoriddim’s DJay, another app that crosses platforms (macOS, iOS, iPadOS), and is now available for the Vision Pro, as DJay Vision (free, $6.99 subscription for pro features, algoriddim.com), complete with virtual decks.

Given Apple’s history as a platform of choice for musicians, it’s not much of a leap to guess that there’ll be more to come, but we’re still rooting for Quest options too.

Breaking down boundaries

VR brings new challenges. For live use, passthrough is the most essential element to consider, if only in terms of preventing you from falling off the stage, otherwise you might need a crash helmet to fit over your VR headset. The Meta Quest 3 and the Vision Pro both use boundary systems, where you can map out the floor space in the room/venue, and whenever you approach the limits of this space, an on-screen representation of the boundary appears to alert you.

Both of these headsets have features where anything or anybody that encroaches on the boundary becomes visible. With AR, when you open an app, or any kind of window, it stays behind as you walk away, and if you look back you can see it in the distance. This kind of location awareness is great as it’s what lets you position your ‘assets’ around you in space. This is also why headsets need a flight mode so when used on a plane, the location awareness is disabled so your windows don’t go flying off behind you.

Both the Quest and Vision Pro remember these boundaries, so next time you wear the headset in the same place, it’s ready to go, no further mapping required. The PatchWorld app includes a resizable, movable ‘window’ that can be used inside a full VR setting, so you can be immersed in that world, but still see what you need, whether it’s the floor, your keyboard, or your bandmates (remembering of course, that VR can be used sitting as well, so the setting of boundaries might be irrelevant to you – but where’s the fun in that?). We’ve found this useful as a way of enjoying the benefits of VR, while also keeping a little back door open just in case.

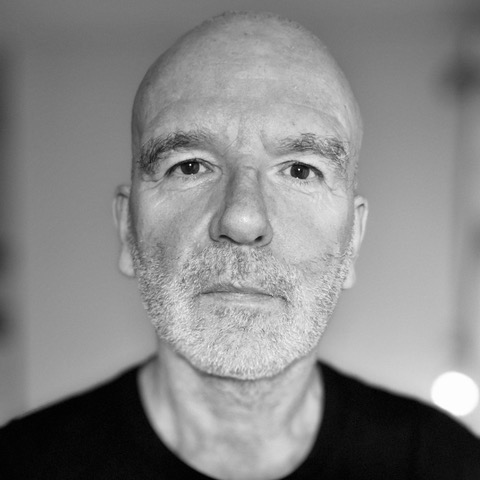

The verdict: Linn weighs in

Roger Linn should need no intro to our readers. The industry titan behind the MPC, the LinnDrum, the Tempest, and the Linnstrument, has decades of experience. As a peerless innovator, it’s no surprise to find that Roger has strong views on VR and AR, particularly as he’s a keen user of both the Meta Quest and the Vision Pro.

"The technology in the Vision Pro is amazing - the possibilities are wide open"

“The technology in the Vision Pro is amazing,” Linn says. “The possibilities are wide open, there are just no apps yet; it’s hard to know what to do with it, as the number of units in the field is low. As a work computer, it’s limited because it’s essentially an iPad OS with enhancements on your face, and even at the high resolution it has, it’s not as good as a retina display on my MacBook Pro. The Quest is lower resolution so there’s less demand on its lower-power processor to run games, display movies, or other things.”

Linn continues, “The problem with VR is that moving your hands in the air is inherently less accurate that playing a keyboard or other tactile interface. So it’s not so good for playing specific notes and chords. However, it’s very good for ‘conducting’ apps— apps that allow you to arrange clips, sequences, beats or loops— because such apps don’t require the same accuracy and tactile feedback as playing notes and chords.”

Roger does spy interesting possibilities in the scope of AR that’s used to add visual enhancements to a physical instrument: “The Piano Vision app (£7.99 – pianovision.com) is a great example of combining the advantages of the physical interface of a real keyboard with augmented visuals.

"An artist who is comfortable with making their own music and working with their own visuals is really well positioned to do something good with this"

“With the ability to use full-body gestures and the capabilities for personal customisation that result from an inherently malleable interface, it starts to merge into dance, and therefore makes for some very compelling performances. I think an artist who is comfortable with making their own music and working with their own visuals is really well positioned to do something good with this.”

At this stage, the solidity of a VR and AR-centred future is hard to point to. VR has immense potential for creative users; we’ve found that working with VR and AR changes our perceptions of how we can interact with musical instruments within the apps. It’s also worth noting just how exciting it is to engage with a rich world of visual creativity. Right now it might not be ready to fully replace our computers or music gear, but it adds a unique way of presenting a workflow, and a fresh creative world view.

Martin Delaney was one of the UK’s first Ableton Certified Trainers. He’s taught Ableton Live (and Logic Pro) to every type of student, ranging from school kids to psychiatric patients to DJs and composers. In 2004 he designed the Kenton Killamix Mini MIDI controller, which has been used by Underworld, Carl Craig, and others. He’s written four books and many magazine reviews, tutorials, and interviews, on the subject of music technology. Martin has his own ambient music project, and plays bass for The Witch Of Brussels.

Don’t miss this record-breaking 100-Hour DJ marathon livestream fundraiser featuring 90 artists

“It's our passion to bring songwriting back to the historic heart of the West End”: An all-new, star-studded writer’s retreat is aiming help make history in London’s iconic Denmark Street