The beginner's guide to sampling from vinyl: "If you make sample-based music and you’ve never dropped the needle on a record, you’re missing out on a world of inspiration"

Forget 128kbps YouTube rips and lo-fi plugins - here's how to do sampling the old-school way

When samplers first came to prominence in the late 1980s, a new era in music was born. The ability to digitise audio made possible the realistic simulation of acoustic and electric instruments, and gave innocuous rack-mounted boxes the ability to become a passable copy of a showroom’s worth of cutting-edge synthesizers.

Where things really took an interesting turn, though, was the moment that music-makers began to sample recorded music and loop, chop, and re-contextualise it into entirely new pieces.

Armed with samplers and grooveboxes from the likes of Akai, Ensoniq, and E-mu, a new generation of artists made classic pieces of work from dusty vinyl, and ‘crate-digging’ quickly became the hobby of choice for nimble-fingered producers and beatmakers.

If you make sample-based music and you’ve never gingerly placed the needle on a record, you’re missing out on a world of inspiration, joy, and - potentially - lightning in a bottle

By the mid-1990s the ubiquity of sampling vinyl in productions spanning the airwaves had piqued the ears of the original artists and, crucially, their record labels’ sizeable legal departments. Over the course of 30 years sampling has turned into big business, and the complexities of legally and equitably distributing the spoils of a hit have made sampling from vinyl finds a treacherous water to chart.

Services like Tracklib promise to take the risk out of sampling existing recordings with a defined royalty structure for songs in their catalogue, and ‘sample makers’, artists creating music specifically intended to be used as a component for other producers and beatmakers to run with, have exploded in popularity.

Lest we forget, our passion for making music isn’t founded on profit. If you make sample-based music and you’ve never gingerly placed the needle on a record, you’re missing out on a world of inspiration, joy, and - potentially at least - lightning in a bottle.

The gear

There’s really not a lot to vinyl sampling when it comes to equipment requirements. Turntables are ten-a-penny, and unless you’re interested in getting hands-on and learning to scratch too then the required specifications of a turntable is pretty much that it turns, and has a speed switch between 33 and 45 RPM — the two speeds that the overwhelming amount of vinyl is pressed to play at.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The accuracy that the turntable can maintain its rotational speed is measured in ‘wow and flutter’ specs, and the smaller these figures the better. It’s certainly not worth getting caught up on though, and the majority of even bargain basement turntables will be fine for sampling on right up until they’re audibly broken. Turntables designed for DJing will tend to have a speed adjustment slider on them, which is useful for adjusting pitch and speed while the record is still generating sound in the analogue domain.

No turntable in sight? The Numark PT01 USB is a great option for beginners, with USB audio output as well as stereo RCA jacks to send to an audio interface or sampler. If you already have a turntable knocking around, whether for DJing with or in the attic as part of a ‘90s hi-fi unit monstrosity, then why not try that?

A standalone turntable will need a preamp to bring it up to line level. This isn’t the same as a microphone preamp, but a quick Amazon search for ‘turntable preamp’ will uncover pages of options for around £20… if you’re in the market for a standalone, though, check to see whether it already has an internal line-level preamp. As a third option, a DJ mixer will have these preamps built in and have the added bonus of EQ to allow you to optimise the sound you’re sampling.

Standalone turntables also usually have replaceable cartridges, the part that houses the stylus which sits in the groove of the record and generates the vibrations that turn into sound. DJ-focused cartridges are a great idea for sampling, as their design is generally more forgiving of a bit of rough-and-tumble and they tend to be more affordable than audiophile-focused hi-fi versions.

Ortofon and Reloop both offer great value cartridges with replaceable stylii, with a single stylus likely to last at least a year of long-term listening. Make sure to follow the setup instructions for balancing the turntable’s tonearm with a cartridge to maximise sound quality and tracking and minimise record wear.

The records

Ah, the fun bit. Vinyl records come in two main sizes and two main speeds. A 12-inch record will typically play at 33RPM if it’s an album or EP, and 45RPM if it’s a single. The faster the record spins, the more information per second is stored in its grooves and so, theoretically, the better it can sound.

There’s nothing wrong with 33RPM, though — the only thing of particular note is that if a record is pressed with beyond 15-18 minutes of sound per side, achieved by winding the spiralling groove that guides the stylus through its duration tighter, it’ll begin to lose quality. Represses and compilations that squeeze as many songs as they can onto a single piece of vinyl are usually noticeably less pleasant to listen to than more spaciously recorded originals and singles.

7-inch records usually play at 45RPM and are made of thinner and cheaper vinyl than their 12-inch counterparts

7-inch records usually play at 45RPM and are made of thinner and cheaper vinyl than their 12-inch counterparts - they were mostly used for singles and were considered more disposable than the ‘full experience’ of a 12 inch record. They tend to have a bold, loud, up-front sound which can be great for sampling, even if they do have a little less detail due to the smaller grooves.

There is a third speed for records: 78RPM. 78s are produced on shellac, a stiffer, heavier material than vinyl, used up until the Second World War. The majority of 78s you’ll find will hark back to pre-war sounds and recording techniques, and so are distinctive in feel, sound, and musical style.

Something all records have in common is that they are, essentially, consumables. The physical process of running the stylus through the grooves of a record will eventually begin to wear the record out, and mishandling vinyl leaves it with dirt and scratches that will be audible, and at worst leave the record unplayable.

If you have a record that’s just too crackly to be listenable, soapy water and a microfibre cloth can work wonders at restoring it

If you have a record that’s just too crackly to be listenable, soapy water and a microfibre cloth can work wonders at restoring it — and playing the record, cleaning it and playing it again (repeat as necessary) can help to drag decades of dust and grime out of the grooves to improve fidelity. If a vinyl is ‘warped’ or ‘bowled’, so that the record won’t sit flat on the turntable’s platter, there’s not a great deal that can be done to rescue it.

Conventional wisdom that suggests trying to press it flat under heavy books or even warming it in the oven will at best do nothing, and at worst destroy the record. If you do decide to move into records for double and triple figures, it’s definitely on you to check them for damage before swapping your hard earned cash - but when they’re from the dollar bin a little (or a lot of) wear and tear is expected.

The tunes

Vinyl is everywhere. Charity shops and thrift stores will almost certainly have a crate or two buried somewhere, and these are great places to find bargains. Don’t expect to find mint copies of an Ahmad Jamal classic, though; the joy of digging for records is largely down to the ‘come what may’ nature of what you’ll find for less than the price of a coffee. It’s tempting to gravitate toward the soul and jazz sections of a record store, but one ‘very good condition’ copy of a recognised album might well cost you a backpack full of dollar bin gambles.

Many of the greatest records of all time were created using snippets from children’s records, marching bands, or a lick from a talented session musician on a crooner’s 27th album

Approaching sampling from vinyl with the intention of finding a classic is misguided. Many of the greatest records of all time were created using snippets from children’s records, marching bands, or a lick from a talented session musician on a crooner’s 27th album (that year). The joy of sampling from vinyl comes from the opportunity to listen to vast swathes of music you’d never get algorithmically apportioned on Spotify, of considering not just the musical content but the texture, the recording, and the context of a sound.

That’s not to say there’s no place for graduating to the pricier stuff, but you’ll have a better appreciation of it when you get to the point that you just can’t bear another stack of James Last, Tijuana Brass, and Command Phonograph Sampler discs.

The sampling

Vinyl’s tactile nature makes sampling a really organic process. Place the needle on the record, and that’s what plays. Spin the record faster to get through it, rewind it manually to get back to something that catches your ear. There’s definitely something to be said for listening to songs in their entirety, but sometimes you’ll just know you don’t need to.

Paying attention to the sounds of the instruments in a song will give you an idea of what you’re hoping to hear with enough separation to sample by itself at some point, and often you’ll be able to find these opportunities by looking at the surface of the vinyl and identifying where the rings of the grooves look shallower and less dense: this is where the quieter, less busy sections of the song are, be they drum breaks or instrumental solos.

We tested 5 of the best stem separation software tools (and the best one was free)

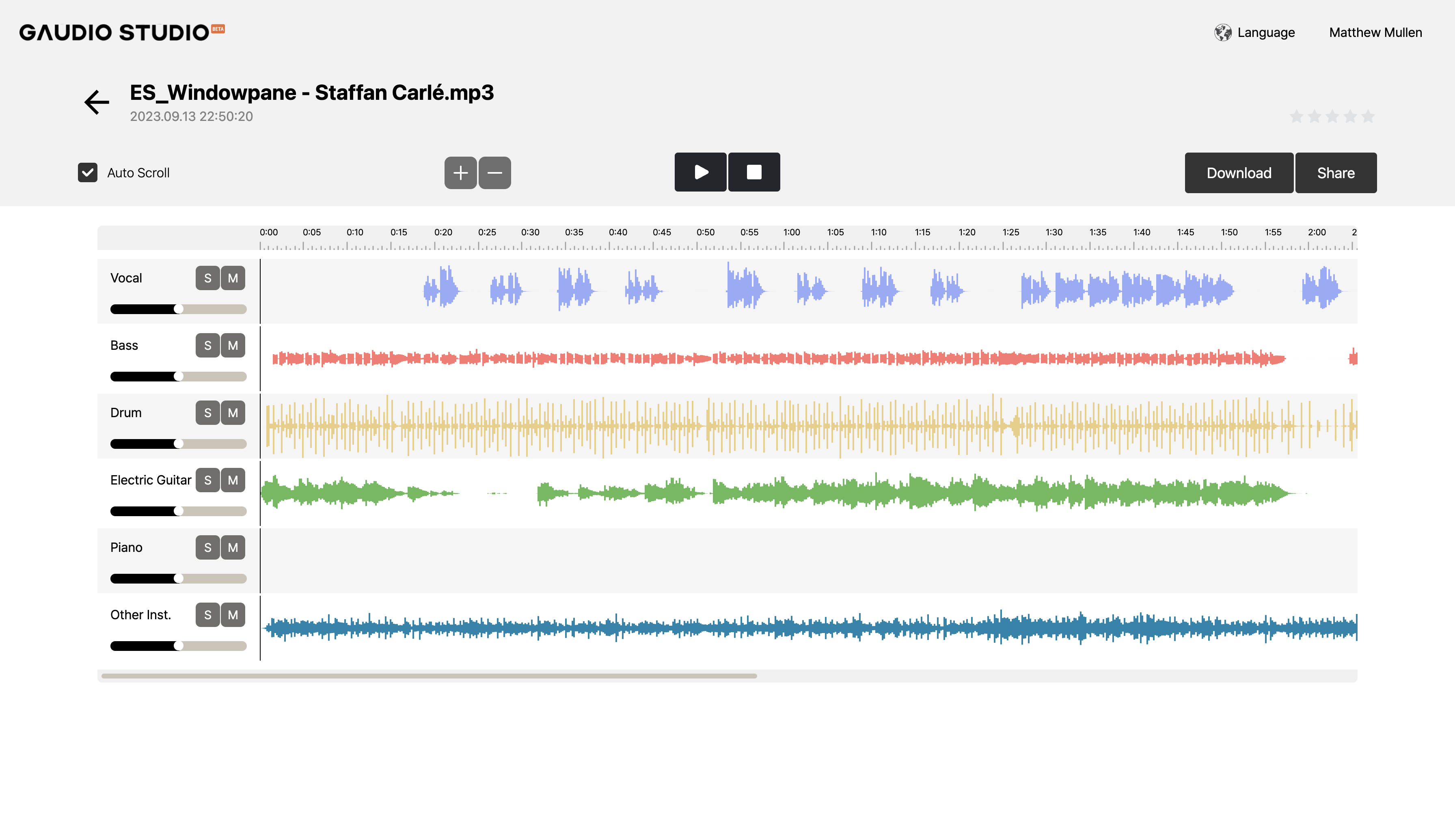

Many stereo records employ very wide imaging techniques, and it’s not uncommon to find one instrument near totally isolated on the left channel while drums are on the right. Separate this out in your sampler and suddenly it’s as if you’ve had access to the individual tracks… well, you sort of have! If this proves difficult, then there's an abundance of stem separation software on the market (both free and paid-for) that can do the work for you by separating out individual instruments from a full mix.

Vinyl sampling forces you to become a record collector. You may not care, but it’s a good idea to note down where you sampled something from for future reference - at the very least it’ll be interesting to look back on, but if you do end up getting label interest in your music, they’re going to want to know. Whether you name your files, tracks, or entire projects with the samples, it’s a few seconds that’ll be worth it in the long run.

Tips and tricks

There’s an undeniable ‘sound’ to vinyl sampled music. It’s a sound that’s aped, often to the point of pastiche, by sample makers: high end roll-off, pitch instability, and punchy, compressed dynamics.

5 of the best free lo-fi tape and vinyl emulation plugins (and one worth paying for)

Actually sampling vinyl will tune you in to what’s actually creating these characteristics, with instability often coming from the tape recordings the songs were pressed from rather than the speed of your turntable (and to a significantly less obvious degree than is often imparted by pitch instability plugins like XLN Audio’s RC-20 Retro Color), and the punchy sound more from the sampler than the vinyl itself.

Many classic samplers were sub-16 bit, and implemented electronics that compressed the dynamics of an input in a pleasing way. If you’re lucky enough to own an original 12-bit sampler like the E-Mu SP1200 or the Akai MPC 60, don’t be afraid to work with your ears instead of the meters and record hot. If you’re more modern in your approach, bitcrushers like D16’s Decimort 2 can help to approximate the squashed, up-front sound.

Another sampler-induced sound associated with vinyl is the grainy, aliased sound imparted by samplers with low sample rates

Another sampler-induced sound associated with vinyl is the grainy, aliased sound imparted by samplers with low sample rates, especially as their rudimentary algorithms resampled and adjusted pitch and speed. The recognisable ring of an SP1200 is accentuated by a classic technique used to make the most of its 10-second sampling time: recording samples in with the turntable playing at 45 and then pitching them down in the unit stretches out the samples and generates a delightfully crushed tone.

If you are a Native Instruments Maschine user you can approximate this technique with the SP1200 engine — it’s not just a bitcrushing effect, it's a pretty effective copy of the way the SP1200 behaves when pitching and filtering samples. Bear in mind that this technique, and others like the instantly identifiable extreme time-stretching of early Akai samplers was borne of necessity and resourcefulness. Experimenting with the way your sampler affects the samples you put into it when you use it in unconventional ways might just give you your own unique sound.

Sampling from vinyl forces an intentionality into our music-making that’s in danger of being lost when dragging entire tracks into a plugin and letting it automatically chop them up for us

The need to be conscious of sampling time is significantly reduced on modern grooveboxes and samplers, and essentially removed entirely with DAWs and plugins. There is something to be said for being selective and decisive when sampling though, and sampling from vinyl forces an intentionality into our music-making that’s in danger of being lost when dragging entire tracks into a plugin and letting it automatically chop them up for us.

Lean into this more conscious way of sampling and who knows, maybe you’ll be on your way to becoming the next Fatboy Slim or Nujabes. At the very least, sampling from vinyl will give you a broader, more varied outlook and something tactile to enjoy in your music-making process. It’s a win-win.

Chris has been making music since 1997 when the box for Mixman Studio Pro called out to him at HMV — the perfect time to watch VSTs get introduced to the world and the computer music revolution gain speed. His experience of producing and performing in the worlds of hip-hop, turntablism, and electronic music saw him featured in legendary publications Hip Hop Connection and RWD, tutoring and managing organisations dedicated to introducing music-making in the community, creating, writing and editing for leading DJ and music production websites during the digital boom, and he now runs howtomakemusic.co from his studio.