“I definitely felt something special in the air that day” – the story of recording Van Morrison's Brown Eyed Girl

Session guitarists Hugh McCracken and Al Gorgoni recalled their memories and vital contributions

Every good function band knows one thing: play ABBA’s Dancing Queen, Come On Eileen by Dexys Midnight Runners or Van Morrison’s 1967 smash hit Brown Eyed Girl and the dancefloor will become a sea of writhing bodies. Even Van, usually dismissive of the track, concedes: “If you can shake your ass it must be all right.”

Brown Eyed Girl comes from a selection of tracks recorded in New York after the break up of his band, Them. Producer Bert Berns signed Morrison to his new label, Bang, and released the tracks as the album, Blowin’ Your Mind!. But while Brown Eyed Girl captured Morrison in effervescent mood and launched his solo career, it would leave a sour taste in his mouth due to poor contracts and unpaid royalties.

All but bankrupt when he recorded the track in New York’s A&R Studios with a team of NYC’s session elite, little could the singer have known that his fortunes were about to change forever.

Morrison, it seemed, was worried that his music was about to be hijacked – again. Cissy Houston, mother of Whitney and one of the backing vocalists on the day, explained: “Van felt burned by the English record company that originally recorded Them. They had packed the studio with session players and changed the sound of the band for commercial purposes. When Van looked around our studio and observed all the players that had been hired he probably thought he was revisiting the London studio where all the trouble began.”

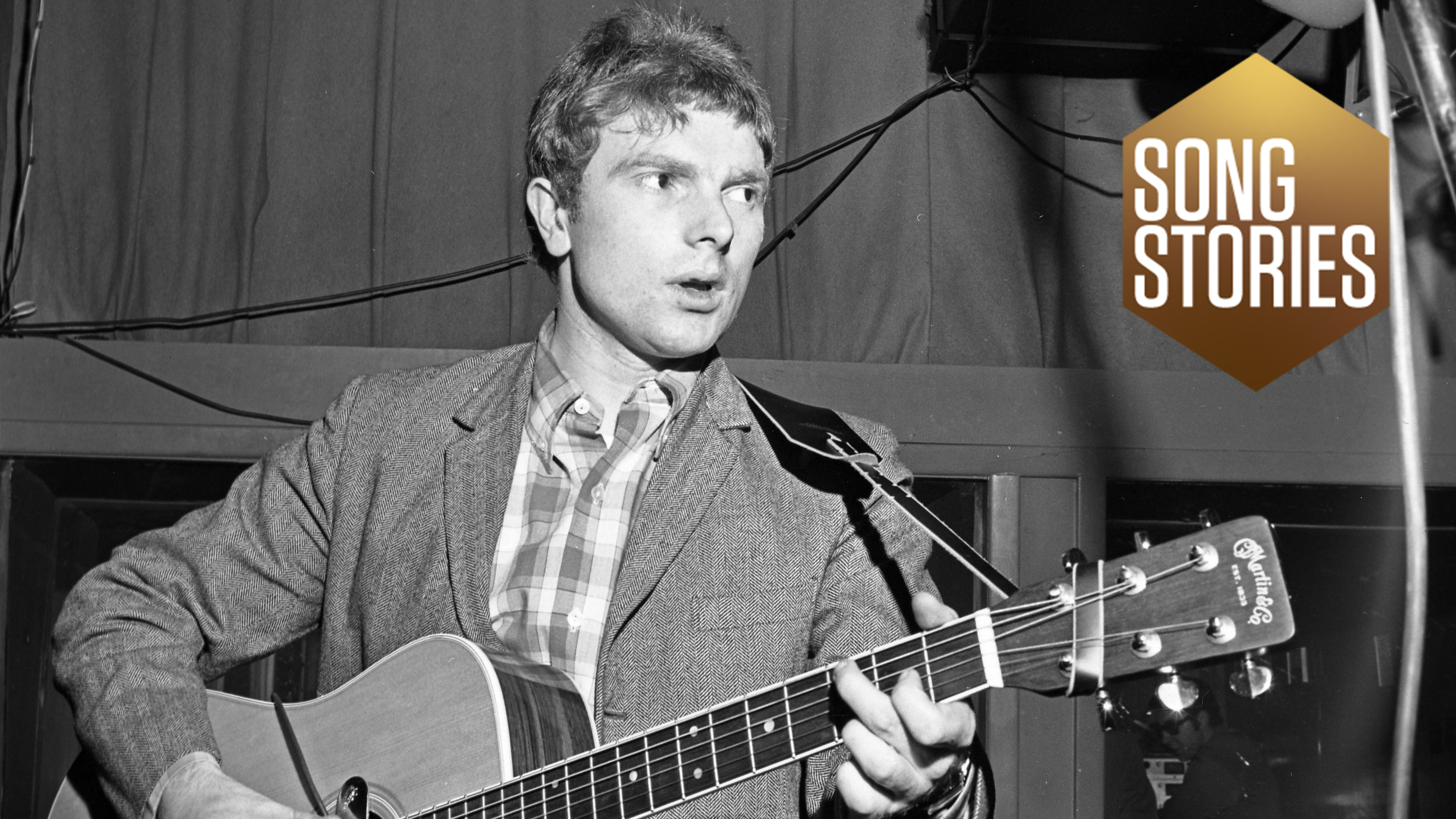

He needn’t have feared. Berns had hired two guitarists, Hugh McCracken on rhythm and Al Gorgoni playing lead. Both were seasoned pros, having worked with the likes of Neil Diamond, Simon & Garfunkel, Bob Dylan and The Monkees and dozens of other '60s chart-busters. Gorgoni recalls the studio clearly. “A&R was between two great music business places on West 48th Street, Manny’s and Jim & Andy’s,” he told Total Guitar magazine in 2011.

“All the rock bands that came through New York made a pilgrimage to Manny’s music store to have their pictures on the wall. Jim & Andy’s was a restaurant and bar that was the local musicians’ hangout. In those days, lots of players frequented the place, and if someone didn’t show up for a date, a frantic call would be made and, sure enough, there would be a player there happy to take it.”

On this occasion our task was more improvisational. More about listening to what was happening, about finding something that was musically appropriate to the situation

Al Gorgoni

“I definitely felt something special in the air that day,” added McCracken, who passed away in 2013. “Arranger Garry Sherman handed out chord sheets and Van sang. He was very introverted until he started singing – and he sang on every take.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Studio musicians are often required to ‘read the dots’ to the most demanding of pieces, but this was more of a ‘feel’ session. “I could read well enough,” says Gorgoni, “but on this occasion our task was more improvisational. More about listening to what was happening, about finding something that was musically appropriate to the situation.”

I borrowed Al’s Epiphone Howard Roberts – I liked it so much I bought it from him after the session

Hugh McCracken

When probed as to whether he came up with that instantly recognisable intro in 3rds, and the fills in 6ths that decorate the rest of the track, Al affirmed the fact with characteristic modesty. Cissy Houston was more direct: “Al Gorgoni devised a figure that became as memorable as the song’s hook,” she said.

Guitar wise, it was jazzers all all the way. “Although I got the call for electric and Hugh for acoustic, it was usually the other way around,” Gorgoni said. “So I used a Gibson L-5 on the neck pickup, through a tweed Fender Deluxe.

In those days the producers left details like tone and pickup selection to the players, although sometimes the engineers would request modifying the sound to get the guitar to work in particular circumstances. It was a transitional time and we would still get calls for combo guitar, usually an archtop with a DeArmond pickup attached to it, so you could plug it in or play it acoustically.”

Hugh played ‘combo guitar’ on the track. “I borrowed Al’s Epiphone Howard Roberts,” he said, “an archtop, oval-hole electric, unplugged but mic’d. Actually, I liked it so much I bought it from him after the session.”

Legend has it that the final version of Brown Eyed Girl was the 22nd take, which Cissy confirmed: “Before the session began he was a shy, withdrawn 21-year-old. But once they rolled the tape he was a live wire, so full of ideas and improvisation that every take sounded like a different song. He was scatting toward the fade like a madman, his eyes closed in the vocal booth, wringing wet after each of the 22 takes.”

Guitarists like Al Gorgoni and Hugh McCracken can look back with pride on careers that have enhanced the music of so many legendary artists. “I hear it in stores or restaurants and it still sounds good to me,” Al said. “It was memorable, and the music created a special vibe. Hugh is a marvellous player and still a dear friend. I’m happy and so lucky to have been a part of the music of that time.”

Brown Eyed Girl had the same effect on Hugh. “I’m proud to have been a part of that. I think everyone there that day felt it was a hit.”

"It’s not to do with gear, it’s all to do with the way the brain sends signals to his fingers" – The story of Dire Straits' Sultans Of Swing

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge