Tom Oberheim: "Thanks to the dance crowd and the Eurorack guys, analogue is back and better than ever"

Synth pioneer on the rise and fall of Oberheim Electronics

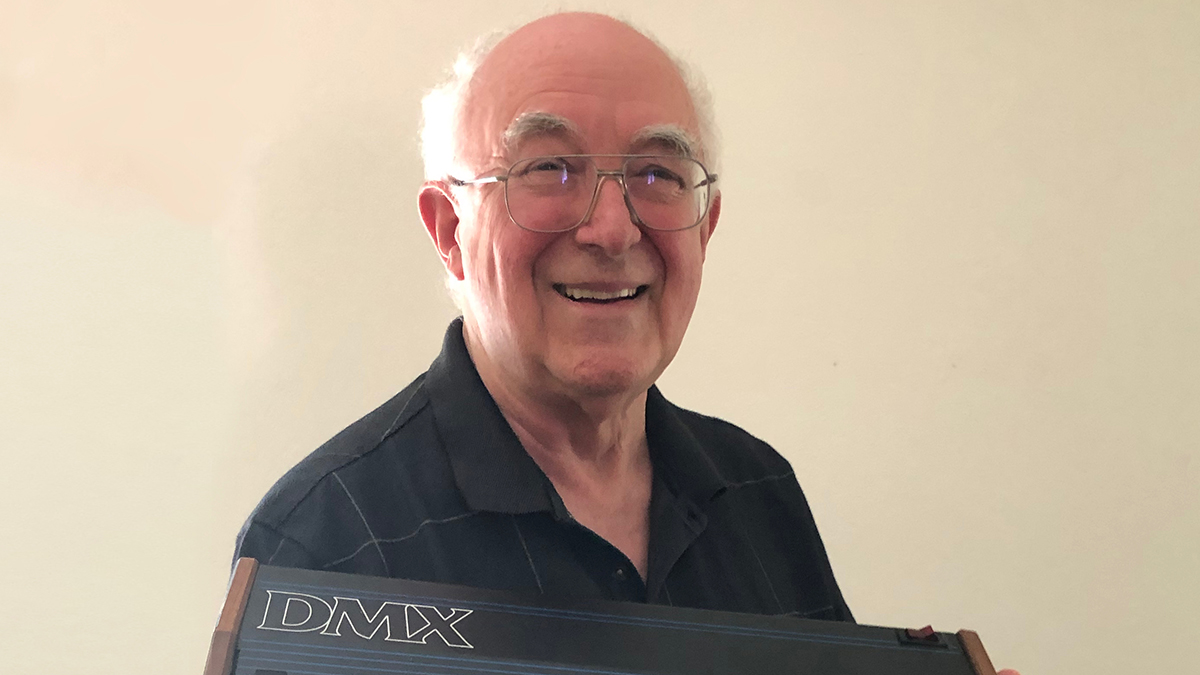

In the '80s, digital may have killed off Tom Oberheim’s legendary analogue synth series, but the 83-year-old’s spark has returned.

Born in Manhattan, Kansas 1936, Tom Oberheim enrolled at the University of California in the mid-‘50s to became a computer engineer. It was here that he met various student musicians and embarked on the creation of ring modulation and phase shifter devices sold by the Chicago Music Instrument Company.

Oberheim became a dealer for ARP Instruments in the early ‘70s before himself moving into synthesiser design, creating legendary analogue synths such as the Oberheim 2-Voice, 4 Voice, OB-X, OBXA and Matrix series. The arrival of digital saw the demise of Oberheim Electronics in the mid-‘80s, yet with Gibson now returning the Oberheim trademark as a gesture of goodwill, the legendary synth maker is set to spring back into action.

You had a jazz background, so what was appealing about designing electronic music instruments?

"Even though I had an interest in jazz, I wasn’t a player. I worked my way through UCLA as a computer engineer, became a professional engineer in 1959 and had to support myself completely going through college so it took me a little longer to get my degree in physics. Although I wasn’t an instrumentalist, throughout the late ‘50s and into the ‘60s I did a lot of choir singing. At one point at college, I was singing in four different choirs and built up some vocal ability."

What did you learn at UCLA?

"I met a lot of student musicians and we all graduated in the mid-‘60s. I started building electronics for some of my friends; simple power amplifiers at first, then a friend of mine who was in a progressive rock band asked if I could build his group a ring modulator. At that point I didn’t have much knowledge of electronic music or know what a ring modulator was, but I went to the UCLA engineering library and came across an article in an obscure electronic publication from 1960 by Harold Boda talking about a modular sound system, which wasn’t a synthesizer, but had a ring modulator in it. That taught me how it could be used in music."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

And from that point, you started making ring modulators?

"I started making them for fun and built a bunch of prototypes. Eventually, I was contracted to build a deluxe ring modulator for the Electronic Music Lab at UCLA and my efforts playing around with them resulted in getting a phone call from a well-known movie composer called Leonard Rosenman. He told me he was doing the music for Beneath the Planet of the Apes and wanted to use a ring modulator on the score. So I bundled one of my ring modulators with a microphone, amp and speaker, took it to 20th Century Fox and they were able to make some sounds that Rosenman liked.

"What was really significant was that several of the musicians in the orchestra came up to me and asked if they could buy one, so that got me into the business of building more. Eventually, I had a complete one that didn’t just have a basic ring modulator circuit but an instrument preamp with the ability to blend the ring modulator sound with a straight sound because it featured a carrier oscillator."

Did you take that to market?

"I was contacted by the Chicago Musical Instrument Company, later renamed Norlin Corp. because they wanted a conversion that they could sell. Norlin, who owned Gibson at the time, was making big stuff like Lowrey organs and were selling some early electronic music devices under the Maestro label, and they contracted small manufacturers like me. So I started building ring modulators with the Maestro name in 1970."

- The 18 best synthesizers and keyboards

- The 11 best semi-modular synths 2019

- The 16 best Eurorack modules

How did you get into making phase shifters?

"I was interested in a sound that a couple of musician friends of mine were enamoured with based on a song from one of the Beatles albums where George Harrison was playing his guitar through a Leslie speaker. So I played around with some circuits and came across one called an all-pass network, which was sometimes called a phase shifter.

"When I built one, it didn’t do anything, or at least I didn’t think it did, so I called a friend of mine, Paul Beaver, who was a pioneer of electronic music and the first person to sell Moog synthesizers on the West Coast. He said you take two tape recorders and put the same signal in both, mix them back together and slow one down so it causes a comb filter effect. So I went back to my phase shifter prototype, mixed the output with the input and had a real working phase shifter. As far as I knew, it was the first phase shifter on the market."

So it was phase shifters rather than ring modulators that put you on the map?

"Well, Norlin gave me a contract to make phase shifters with the Maestro name on it. Between 1971 and 1974, I built 75,000 of those, which did put me on the map, but I was still looking to supplement my income and Beaver had shown me some of the interesting things you could do with a Moog modular system. This was around 1971, and although I wasn’t exhibiting at the NAMM show I started going there. ARP was doing pretty well at the time and I knew there weren’t any music stores in Los Angeles selling ARP, so I went to their booth and asked if they’d let me be their dealer.

"In those days, music stores weren’t that interested in synthesizers, but I prevailed so they said, okay you can be our dealer. I had a Rolodex full of names of musicians in the LA area that had bought ring modulators, so I started selling ARP synthesizers to them, which was quite a change for me. I didn’t see myself being a synthesizer manufacturer; I just enjoyed selling them to some fairly well-known artists at the time and had a nice little business going."

So how did you end up making the DS2 digital sequencer?

"In the ‘60s I’d designed numerous computer devices and systems using digital logic. There were no microprocessors in those days, so you had to build digital devices out of logic gates. I’d seen analogue sequencers at Paul Beaver’s place and got the idea to make a sequencer that you could play on a synthesizer keyboard and load the notes into its memory, so I built a digital sequencer that I sold to a bunch of people around the country called the DS2, and later the DS2A. That was interesting.

"Because of the price of memory chips in those days, it had a total of 1024 bits, which is 128 bytes. It wasn’t organised as bytes, but it was a tiny fraction of a megabyte and a chip cost $25. However, there was a problem with that concept. If you used your ARP 2600 or Minimoog to load notes into my digital sequencer, you could play the sequencer back through the synthesizer or play the synthesizer from the keyboard but you couldn’t do both."

How did you find a solution to that?

"I came up with the idea to make a synthesizer expander module that allowed you to load a sequence into the DS2, play it back through the synthesizer module and still be able to play the keyboard. By 1974, I was selling a lot of pedals. I was also selling ARP Odysseys, so I had an idea for a pedal that used the Odyssey’s sample-and-hold circuit along with what we called an envelope follower to do what the Mutron pedal basically does. So my main business was selling three or four pedals plus a few digital sequencers and SEMs."

At that point you hit a brick wall with Norlin?

"In January 1975, my contact at Norlin called me to say business is bad, we’re cancelling all our orders and we don’t expect to be buying anything else from you in the future. It was like, oh boy, what do I do now? By then I knew quite a bit about the synthesizer business.

"I knew about Emu, the Moog, the ARP and the Putney, so I got the idea to take four of my SEMs, license the scanning polyphonic keyboard that the Emu had for its modular system and throw it all together. By June 1975 I was at the NAMM show with a working prototype that was ultimately called the Oberheim Four Voice, which could also be expanded to an Eight Voice."

... there was a guy there called Dave Smith who had a thing called the Prophet-5, which did everything that the Four Voice didn’t... so it was clear that I was going to have to do something or I’d be out of business by the end of 1978.

How was it received at NAMM?

"The price of the Four Voice was $4,000 and I remember the owner of New York’s Manage Music coming to me and saying “$4,000? Nothing in my store sells for more than $1,000!” But I did get some orders and also had a good friend called Stephen St. Croix who was a columnist for Mix Magazine. He asked if I’d like to meet Stevie Wonder who was in a studio in Hollywood making Songs in the Key of Life. My Four Voice prototype wasn’t in production yet, but we went to the studio where Stevie was recording, set it up and he played it a little and asked to buy it.

"That’s the last I ever saw of that prototype, although I was at a NAMM show three or four years ago and Stevie and his entourage came by to see my new synthesizer and one of his people told me they’ve still got that synthesizer in storage [laughs]."

Could you foresee that these instruments would play such an enormous role in modern music?

"No, it wasn’t that way at all. synthesizers came into the mainstream very slowly on records and concert tours and I was right in the middle of it fighting to stay alive. Some years were good and some were tough, but it was exciting because I saw these obscure, strange electronic devices, which were really just pretty straightforward circuits, doing marvellous things."

So you brought the Oberheim Four Voice into production?

"For a couple of years I had the only true polyphonic synthesizer that you could buy in a music store and my company started growing real fast. Some great music was made with the Four Voice and Eight Voice in the 1976-1980 timeframe, but in the spring of ‘78 NAMM held a West Coast wintertime show at the Disneyland Hotel in Anaheim, California. It was a very small show but there was a guy there called Dave Smith who had a thing called the Prophet-5, which did everything that the Four Voice didn’t. It had autotune and was completely programmable, so it was clear that I was going to have to do something or I’d be out of business by the end of 1978."

What effect did the Prophet 5 have on your business?

"Sales of my Four Voice and Eight Voice were dropping precipitously, but I had an engineer working for me called Jim Cooper and we put our heads together and said we better do something. Between November 1978 and June 1979 we developed the OB-X - a project that would normally take a year but took us six or seven months.

"When I went to the NAMM show in the summer of 1979, I got to Atlanta wondering if by the end of the show I’d still be in business because the Prophet-5 was smoking in those days, but by the end I’d written about half a million dollars of business for the OB-X in around three days."

Presumably, this is where the legacy of Oberheim synthesizers began?

"Yes, because from that I created a bunch of products from the OB-X to the OBX-A, the OB-8, Matrix Pro, Expander DMX and the DSX. By 1985, my company had grown to about 100 people and was doing really well. However, we were developing the Matrix 12, which was only two or three months’ late but because I’d bought a lot of parts and paid for them in advance we ran into cash flow problems.

"To cut a long story short, by June 1985 the bank decided to foreclose on the company and seized and sold the assets to another outfit. It was a long and difficult time for me. The demise of my first company happened in such a way that it’s not just an ugly story, but I didn’t come away with any Oberheim equipment.

"I became a consultant for Roland in the late-‘70s/early ‘80s and started another synth company in the mid-‘90s but the product was not successful, so I got out of the business and worked in Silicon Valley for the next 10 years, but not in music."

Did you put your demise down to the digital revolution?

Everything was turning digital. The Yamaha DX7 started the digital revolution in 1983 and then there was the Korg M1and the Roland D50, so analogue became pretty much dead.

"Dave Smith’s Sequential Circuits went under in 1986 and by then I knew Roger Linn really well and his first company went under. Everything was turning digital. The Yamaha DX7 started the digital revolution in 1983 and then there was the Korg M1and the Roland D50, so analogue became pretty much dead.

"It became a different world because people wanted perfect strings, perfect brass and a perfect Fender Rhodes that didn’t weigh 200 pounds. Of course, there were people making great sounds with digital stuff, but it was bittersweet."

Tell us how your friends helped get you back into the industry?

"I’ve known Dave Smith both as a friend and competitor since 1978 and watched as he got back into the analogue synth business. At first I thought Dave could do it because he’s got some skills that I don’t, but finally in the summer of 2009 I was having coffee with Roger Linn and he said, “Tom, you know what you need to do? You need to bring back that synthesizer module you had.” So I thought about it for a while, then started making SEMs again and selling them in 2009, which did pretty well.

"Since the Oberheim days, my favourite machine was always the Two Voice. I used to have a lot of fun with it even though I didn’t own one. After selling SEMs three of four years ago I decided to revive the Two Voice, making a much more complex sequencer than the original had. I had component problems, so I wasn’t able to fulfil all the dreams I had with the Two Voice, but at least I was back in business and that pretty much brings us up to now."

What’s your opinion on the rise of Eurorack?

"Two things happened when the new century arrived. Dave Smith got back in the business in 2005, but the other thing was this growing monster called Eurorack. Thanks to the dance crowd and the Eurorack guys, analogue is back and better than ever. It was a bumpy ride for someone like me that had been so involved. I was the second generation - the first generation was Bob Moog and Donald Buchla, but here we are and the synths are back thanks largely to the dance producer folks.

What direction do you think everything is heading, and what direction what you like to see it head?

I was 83 years old in July but I still love what I’m doing and I’ve learned after 50 years not to put on a guru hat because once you do that the world either turns on you or lifts you up and carries you along.

"The elephant in the room is the increasingly lower cost of good-sounding gear. Of course, it depends on where you draw the line, but if you go back 50 years things cost $4,000, then $3,000, then $2,000 and so on. Now you can get the Teenage Engineering gadget for $80.

"I was 83 years old in July but I still love what I’m doing and I’ve learned after 50 years not to put on a guru hat because once you do that the world either turns on you or lifts you up and carries you along. I’m still in the business and hope to have a new product out by the end of this year, and I’m also hoping to get back into the polyphonic synthesizer business next year."

What can you tell us about this new product?

"[Laughs] Stay tuned."

When did you first hear about Gibson returning the Oberheim trademark and intellectual property to you, and what did that gesture mean to you?

"It’s been a very exciting event. It was largely due to the efforts of one of the founders of Line 6 called Marcus Ryle. I hired Marcus at Oberheim in 1980 when he was 18 years old and his first project was the Oberheim DSX Sequencer. It was Marcus who went to the new CEO of Gibson and evangelised him to the idea of doing something that would be great for me and Gibson from a goodwill point of view."

To find out more check out the Tom Oberheim website.