“To play music, you have to understand it. I didn’t understand Topographic Oceans. That’s why I hardly played on it": Rick Wakeman and Yes - firings, hirings, curry, catastrophe and chaos

Best of 2023: When Vangelis nearly joined Yes and other tales from topographic oceans…

Join us for our traditional look back at the news and features that floated your boat this year.

Best of 2023: Perhaps no other band has a chequered past as patched together as Yes. As their music tumbles through the ages, from rock to prog, nudging into pop before bouncing back again, the band’s themes and cast of characters come and go without fan complaint.

Yes have perfected the art of regenerating like a hairy Doctor Who whenever their accountant sounds the alarm

More akin to a manager picking their FA cup squad or a WWE tag team than any notion of band chemistry or working relationships, Yes have perfected the art of regenerating like a hairy Doctor Who whenever their accountant sounds the alarm.

While their comings and goings are too long and arduous to list, it’s perhaps the band’s love/hate, will-they-won’t-they relationship with keyboard player Rick Wakeman that stands out amongst the wealth of mid-season sackings and signings.

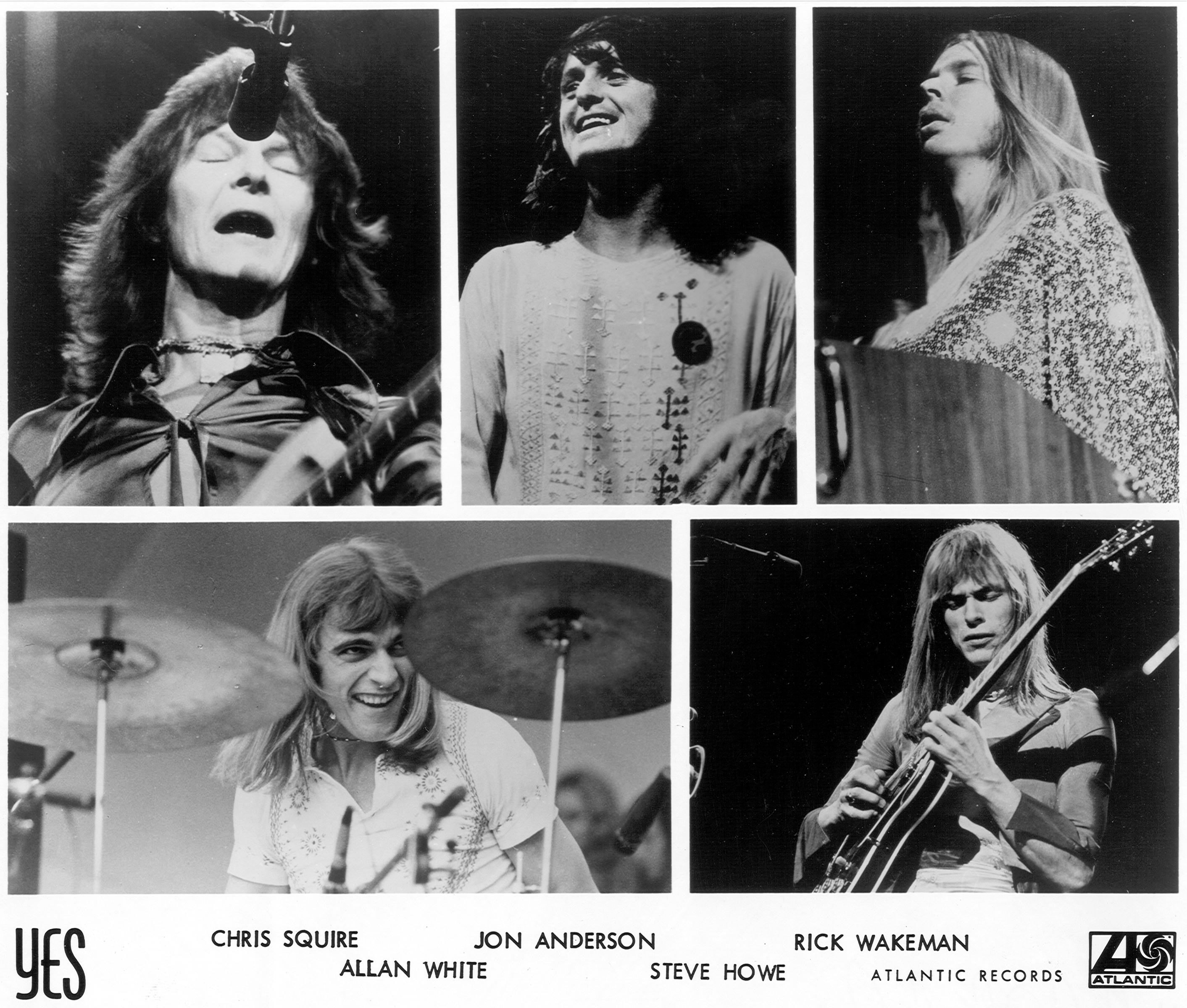

Yes’s quest for prog dominance began at their inception in 1969, but true success only really came with their third album, The Yes Album. Founding members vocalist Jon Anderson and bassist Chris Squire had, by then, offed original guitarist Peter Banks in favour of Steve Howe and would soon develop quite the taste for pushing members through the band’s revolving door.

New guitarist Howe had found critical success with Bodast, Tomorrow and fleetingly joining ELP’s Keith Emerson in The Nice for an entire day… An inspired and in-demand player he quickly took Yes in new more experimental directions and swept in a new brace of ideas that the band hoovered up, not least the notion of supplementing the increasingly ambitious five piece with some of those new synthesizers…

We were like, let’s try the Moog and the Mellotron. Tony didn’t really want to...

Jon Anderson

The synths of the day – wardrobe-sized Moogs and the primitive tape-driven ‘sampler’ the Mellotron – were still radically new instruments, looking for a home in the modern pop, folk and rock landscape. But their power to impress was something that new-guy Howe was eager to get into the stuffy Yes arsenal and soon had Squire and Anderson onside.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Resident keyboard player Tony Kaye, however, had other ideas. “We were like, let’s try the Moog and the Mellotron,” says Anderson in Yes: The Authorised Biography by Dan Hedges. “Tony didn’t really want to. You can dig that for six months but then you realise that it’s holding you back.”

The fact is that Kaye was a little stick-in-the-mud. While classical training and innate skills are a boon for prog rockers – and abilities that Kaye had in spades – Kaye was also a little too in love with the purity of his Hammond organ and piano.

Just as asking Howe to replace his Gibson ES-175D with a banjo would be a little off-piste for prog, so Kaye regarded the replacement of his beloved Hammond and piano duo with synthesizers as similarly off limits… Synths? In rock music? Nonsense.

Schooled by an admiration of classic rock keyboard players – Brian Auger, Keith Emerson, Jon Lord – Kaye had the role off pat. Piano plus Hammond. Done. But the band had grown increasingly weary of Kaye’s refusal to play with more than one hand – more often than not waving the other aloft in homage to his heroes – and, by resolutely sticking to his weapons of choice, Kaye had committed the cardinal sin of prog… That of not wanting to progress…

With Kaye and the rest of the band at an impasse and a long and winding (and grumpy) America tour in progress the band began to plot their next moves… without Kaye.

The Wake Up Call

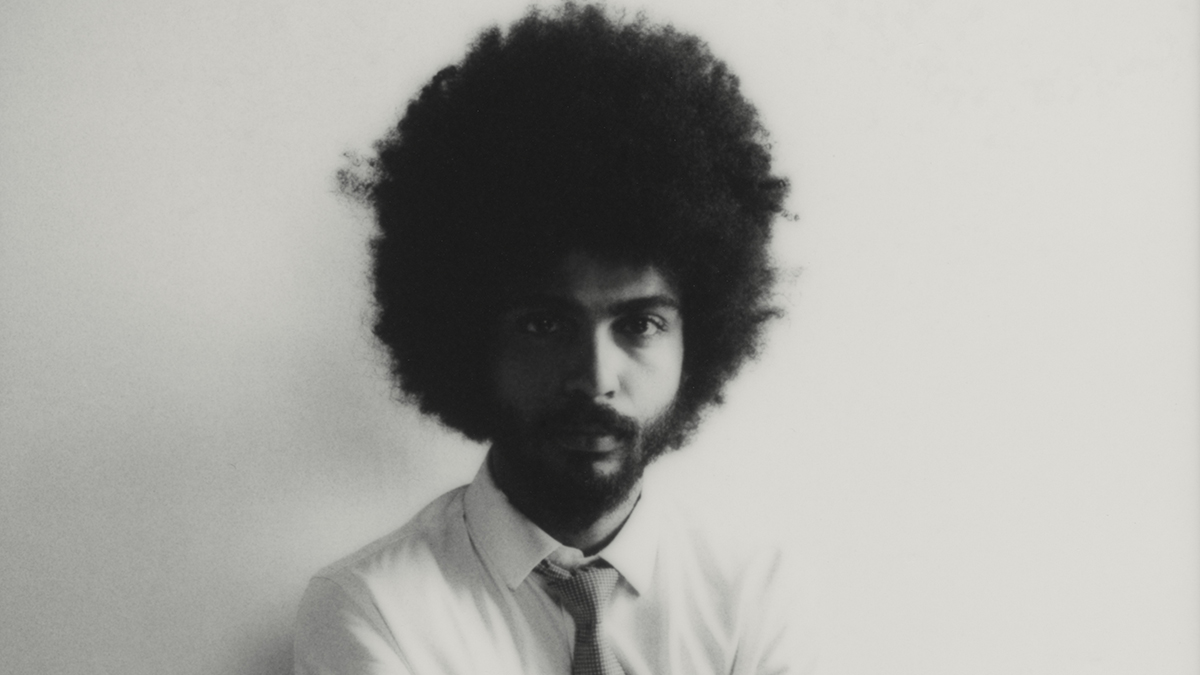

It was the cover of the Melody Maker that sealed the deal. “Tomorrow’s Superstar” had been the headline, with a gushing feature inside extolling the keyboard skills of one Richard C Wakeman.

Then part of The Strawbs – a folk band gone electric – he was a prime exponent of both the synth dark arts and drinking and socialising with writers from the serious ‘inkies’. Thus his buddy, the writer Mark Plumber crafted him the ultimate CV and its timing couldn’t have been more perfect.

It fell to Yes’s Chris Squire to make the call. Still on US time after returning from that grouchy tour with Kaye, Squire made the call to Wakeman… at 3am…

“I had been doing a lot of sessions and was lying in bed after having done a three-day stint with about six hours sleep,” says Wakeman in Dan Wooding’s book The Caped Crusader.

“And then the phone rang… I could hear the conversation “He’s only just come in… He’s really tired…” I was furious. “Gimme the phone… Who’s that!?” I said. “Oh, hello, it’s Chris Squire from Yes… How are you?” went the other end. “You phone me at three in the morning to ask me how I am?!” “We were thinking of having a change of personnel and I wanted to know if you’d be interested in joining the band?” "And like a berk I said “No!” and slammed the phone down…

"I woke up the next morning and asked “Who was that on the phone?” I raced through my record collection and pulled out Yes’s Time and a Word. I hadn’t really got into it that much but I played it and I thought “Yeah… This is interesting. Maybe I shouldn’t have said ‘no’ to Yes after all…”

It fell to band manager Brian Lane to clinch the signing. “When the group said they wanted to replace Tony Kaye I immediately recommended Rick, but they were doubtful because he was still playing with The Strawbs.

"Anyway I phoned Rick and said “Do you want to join Yes?” and he said bluntly “No.” So I asked him why and he explained his position with The Strawbs. I then offered him £5 a week more than he was getting and Rick, being a man of very strong principles said “I accept…”

Speaking to Melody Maker at the time of his departure Kaye said “I’d not been happy with the band for a year really and wasn’t getting into the new music they were playing. It was difficult to get my ideas across and in the States we were drifting apart socially.”

And that was that.

“Something I get asked about is my leaving Yes because of my disdain for the ‘new’ electronic gear - the Moog and the Mellotron - and there’s a lot of truth in that.” Kaye admitted to MusicRadar in our interview in 2021.

“I did eventually use them but I was somewhat of a purist. I just loved the textures and the sound of the Hammond. The ‘new’ equipment didn’t really appeal to me. And, of course, it was all out of tune. So it was very difficult for me to get into.”

Within two months of Squire’s call, Wakeman was touring to promote the new album, Fragile while Kaye waived the rights to his already recorded input in exchange for £10,000 upfront.

Fragile proved to be the album that broke the band internationally and its successor Close To The Edge cemented their success making number four in the UK and number three in the States. However, by the time of its eagerly-awaited follow-up things were not going well.

The four-sided sea monster

Beaten to death by the Topographic stick – a project he referred to as “Tales from Toby’s Graphic Go-Kart” much to the annoyance of the rest of the band – Wakeman began to plot his escape.

Tales from Topographic Oceans is a ‘classic’ for perhaps all the wrong reasons. After touring hard the band not only found themselves up against a deadline for their next LP but Anderson’s desire to make their next album “something extra” would soon stretch them beyond their limits.

Oceans underwent a tortuous, lengthy recording process in multiple studios around the world. At one stage Anderson grew frustrated with the sound of his vocals in the studio, asking why he didn’t sound as good as when he sang at home in his bathroom.

Engineers were directed to build a bathroom – a wooden, tiled box – in the studio inside which Anderson could perform

Thus engineers were directed to build a bathroom – a wooden, tiled box – in the studio inside which Anderson could perform. The endeavour came to naught as not only did the room not produce the required reverberation but, thanks to only being glued on, the tiles would drop off mid-take.

But it was the album’s ambitious stretching of thin ideas that was its ultimate undoing. With just four songs across its four sides, Tales from Topographic Oceans is the embodiment of the cliche of what happens when great musicians set out to ‘explore’ but only get as far as disappearing up their own arseholes.

Like having amps going ‘up to eleven’ or lowering a papier mache Stonehenge on stage, TFTO has passed into risible fantasy. But this is no Spinal Tap. This really happened, and Oceans crashed against a line in the sand marking where prog had gone too far.

To play music, you have to understand it. I didn’t understand Topographic Oceans. That’s why I hardly played on it - It frustrated me no end

Rick Wakeman

After successfully steering the band into pastures new following the departure of stick-in-the-mud Kaye, Oceans left Wakeman adrift as the rest of the band increasingly upped the ante and lost their way.

And as if spending six months wrestling an 83 minute four-song concept monster into life wasn’t painful enough, the band chose to tour it, playing it in its entirety to enraptured (read: captive) fans – for five more months across Europe and the States in 1973 into 1974.

“To play music, you have to understand it. I didn’t understand Topographic Oceans. That’s why I hardly played on it,” Wakeman complains to Dan Wooding in his book The Caped Crusader. “It frustrated me no end and playing the whole thing on tour, I got farther and farther away from it. I felt sorry for anyone who saw us for the first time on that tour. All they got was Topographic Oceans shovelled down their throats.”

Thus, beaten to death by the Topographic stick – a project he referred to as “Tales from Toby’s Graphic Go-Kart” much to the annoyance of the rest of the band – Wakeman began to plot his escape. But first… dinner…

“I was really struggling with the album and tour,” writes Wakeman in his book Grumpy Old Rock Star. “There were a couple of pieces where I hadn’t much to do and it was all a bit dull. The faithful had mixed opinions about Tales from Topographic Oceans. Half the audience were in narcotic rapture on some far-off planet and the other half were asleep, bored shitless,” he explains.

Thus – after previously describing his hankering for a curry – one night his helpful keyboard tech upped the ante and took Wakeman’s disdain for the band’s quad-sided opus public by delivering his boss’s dinner mid-gig. Mid-song in fact. A chicken vindaloo, pilau rice, poppadoms, a stuffed paratha, Bombay aloo and a bhindi bhaji to be precise. All laid out atop the Hammond, keyboards and Mellotron in front of the audience and a band of vegetarians…

The mid-gig meal proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. Wakeman was already spending more time in the bar with journalists than with his compatriots and, post-tour, was dodging kiss-and-make-up calls from manager Brian Lane.

Wakeman quit the band via telegram soon after. Besides, by then Wakeman had enjoyed solo success with his Journey to the Centre of the Earth LP and would soon play his legendary King Arthur On Ice gigs… But that’s another story.

Prior to becoming the band’s resident tutting vibe-hoover, Wakeman had delivered a flamboyance, an extra gilding on their bombastic lily and a whole new smorgasbord of synthetic sound.

Post Wakeman, Yes were in chaos. For once a band member had chosen to leave and Yes had lost a major part of what had made Fragile and Close To The Edge hits. Anderson knew that a direct replacement would be hard to find but there was perhaps one man who could fill Wakeman’s considerable void…

Chariots on hire

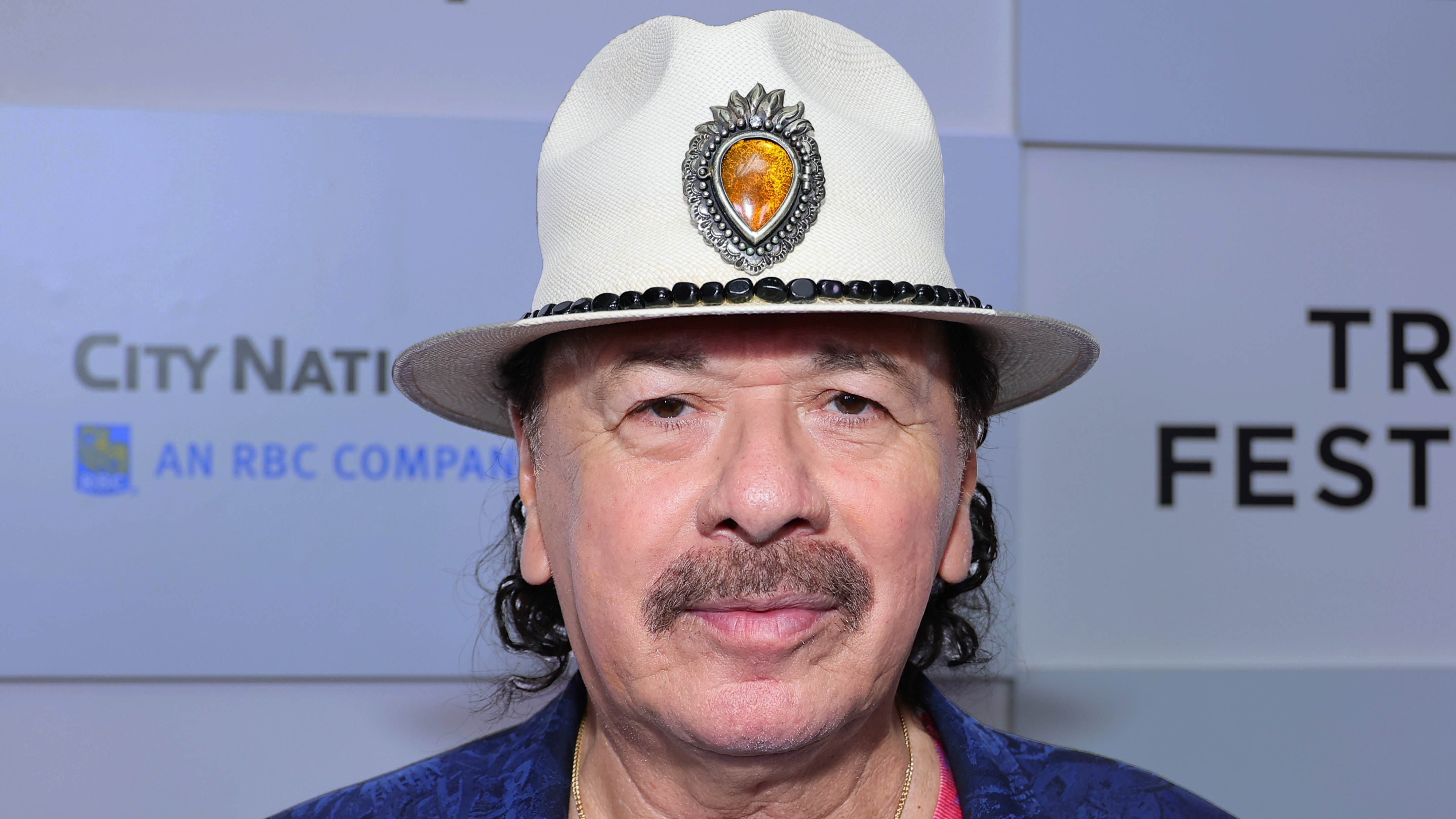

Aphrodite’s Child were – basically – Greek Yes. The moussaka to Yes’s mince. The feta to their cheddar. Experimental, wild, alternative and tangibly psychedelic they were driven at their core by one Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou aka Vangelis on keyboards. With his solo star status and movie-scoring days ahead of him, Vangelis’ Chariots weren’t exactly on fire but they were certainly warming up nicely.

The flamboyant, energetic star in the making was already sufficiently well known and respected on the rock scene to attract Anderson’s eye. A healthy portion of spicy Greek meze into Yes’s stodgy prog buffet felt like just the Rennie they needed post Wakeman currygate, and with no intention to step backwards into stoney-Tony Kaye territory again Anderson coaxed the effervescent Vangelis over to England for an extended audition.

“Ah! The Drums!,” he [Vangelis] would say and play like fury for 10 minutes, like some virtuoso at a drum school - “Ah, very good drums, hah?” and he’d crash around like the drummer from the Muppet Show…

Steve Howe

For three weeks Vangelis jammed with the band to prove his worth. While his talents were obvious, his ‘fit’ with the battle-worn tried and tested prog-ers was soon in question.

“He was pretty overpowering,” Steve Howe explains in Yes: The Authorised Biography. “We could see the musical possibilities right from the beginning, but we were a bit confused. He was very non-committal and we were unsure if he was going to stay. We played great music for half an hour and we were sure he was the right man.”

But Vangelis’ wild side soon got the better of him. “Okay, let’s try this song now, we’ve worked this bit out so just play along,” suggested Howe at one point. “But he couldn’t understand anything we said. He wasn’t used to playing in a group. He was an entity. A sound. And that entity was called ‘Vangelis’.”

And when the Greek went on to reveal his hidden talents he was unwittingly pushing the keyboard hotseat further away. “Ah! The Drums!,” he’d say and play like fury for 10 minutes, like some virtuoso at a drum school,” says Howe. “Ah, very good drums, hah?” and he’d crash around on them some more, like the drummer from the Muppet Show… Everybody greatly admired him but it was like “Uh… Could we play this song now?…”

Thus despite his energy and multi-instrumental musicianship Vangelis didn’t earn so much a ‘Yes’ as a ‘no’. Instead they opted for Swiss keyboard player Patrick Moraz, who was part of the band Refugee with ex members of The Nice, effectively replacing Keith Emerson.

While a gifted composer with movie soundtracks under his belt, the Yes job was the hottest gig in town and Moraz was secretly summoned to the same rehearsal space where Vangelis still had his keyboards set up. Borrowing the maestro’s gear he impressed the band with his ability to improvise a new intro for their in-progress track Sound Chaser (which became the version recorded on their next LP Relayer) and the job was his.

I’ll be the roundabout…

However, despite Relayer success, Moraz wasn’t allowed to get too comfortable. Predictably, after just one album Moraz was offed in favour of… unpredictably, Rick Wakeman, who was cajoled into rejoining the band after session duties on their next album Going For The One… before being replaced by The Buggles keyboard player Geoff Downes in 1980… before being replaced by – you didn’t guess it – the return of Tony Kaye in 1983…

Kaye returned to the most vacated hotseat in rock for the band’s Owner of a Lonely Heart renaissance (their most successful period ever, spawning the hit 90125 album). But had the synth-hating virtuoso learned his lesson? Nope.

As soon as recording commenced Kaye promptly fell out with producer Trevor Horn over – you guessed it – the amount of technology on board and the degree to which Kaye’s keyboard talent was being employed.

However, after being almost absent throughout the recording, he did have the sense to embrace the tech, becoming the keys anchorman for that album’s subsequent tour and live recording.

A happy ending then? Remember, this is Yes we’re talking about… But there are too many Wondrous Stories to tell. Don’t get us started on Anderson’s departure and subsequent return to Yes post Drama LP. And the birth (and death) of spin-off Yes monster Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, Howe… Those are tales from other topographic oceans…

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

“An amazing piece of history from the British blues scene”: Robert Plant is selling a trove of gear for charity – including a John Birch-modded ‘62 Stratocaster with two switches that once belonged to Stan Webb of Chicken Shack

“I was like ‘Wow, Coldplay were definitely listening to Radiohead and trying to make their version of it’": Porter Robinson says that he only recently discovered that Coldplay used to sound a bit like Radiohead

![Gretsch Limited Edition Paisley Penguin [left] and Honey Dipper Resonator: the Penguin dresses the famous singlecut in gold sparkle with a Paisley Pattern graphic, while the 99 per cent aluminium Honey Dipper makes a welcome return to the lineup.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/BgZycMYFMAgTErT4DdsgbG.jpg)