"To say its arrival was earth-shaking would be no exaggeration": why, 40 years on, the Yamaha DX7 was the most important release in synth history, even though it did "make your head dribble"

And why 'important' doesn't always mean 'best'…

It's the 40th anniversary of the Yamaha DX7, so the ideal time to look back at its impact, legacy, and what reviewers thought of it on its release. You may not think it's the best synth of all time – and we'd agree with you there – but we'd definitely argue it was the most important, and not always for the right reasons.

We might as well start with a stat – and what a stat. In 1986, up to 61% of the US chart was dominated by the electric piano preset from the DX7. Yes, we couldn't quite believe it – and more on that later – but just to give you a flavour of the DX dominance, the synth featured on this…

And this…

While Tina Turner apparently went all out with a DX7, with three presets (15-Bass 1, 24-Flute 1 and 20-Caliope) used in this small hit…

And how could we forget this?

So is this why the DX7 is the most important synth in history? Well, there's actually a lot more to the story than popularity. After all, not everyone likes a preset.

We'd even argue that the DX-7's negatives were important to its 'icon' status.

On the plus side, the DX7 sold more than most, made digital synthesis popular, was used on those countless hit records and had (largely) great sounds. Conversely, it was a pig to program and it gave rise to 'the digital synth era', the first wave of which wasn't a great time for all synth heads (although the second wave we're enjoying now most certainly is).

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

However, with our 'always glass half full' approach, we'd even argue that the DX7's negatives were important to its 'icon' status.

The digital synths it kickstarted helped with the development of the synth VSTs we use today, and the reaction against their often horrible menu-diving and harsh sounds eventually gave rise to a return of the analogue synths that we have been enjoying for the last 15-odd years, and also the new breed of hands-on digital synths that have been around for the last five.

Yes, we are turning a negative into a positive, but if you follow our logic – and you really don't have to, but we're the ones writing this feature, so it might help – it means that, yes, the DX7 was the most important synth release of all time. It certainly wasn't the best synthesizer ever released, but its impact is up there with the Minimoog's.

But did anyone realise that at the time? As a matter of fact, mostly yes. As much as we'd love to pick through the old reviews of this classic Yamaha and point and laugh at them, most got it spot on. 'Most', that is…

First we turn to Dave Crombie, in a magazine called Music UK, who in August 1983 said: "FM Digital Synthesis is without doubt the most exciting new development of the decade.

"At £1,299 it [the DX7] is ridiculously cheap. You couldn't have imagined that an instrument of this versatility and power could have been produced for anything like this price, even as recently as a year ago. The DX7 is going to be a winner, and I reckon would be well worth the money at £2,000."

When you've finally mastered programming, you'll never want for a sound

The prediction was right, then, although we'd argue that £1,200 – about £5,000 in today's cash – was not exactly 'ridiculously cheap'.

"We reckon that the DX7 is the proverbial 'bee's knees'," Crombie went on to say, noting its stunning presets and that "when you've finally mastered programming, you'll never want for a sound."

He got even more accurate with, "it gets my vote for instrument of the year (maybe even of the decade)," although the Roland D-50 might argue with both of us on that latter score.

Meanwhile, Mark Jenkins was equally positive in Electronic Soundmaker & Computer Music in November 1983. He wasted no time with his opening statement: "The DX7 is destined to be one of the keyboard classics along with the Fender Rhodes, the Minimoog and the Wasp."

We were with Mark until 'Wasp' but still, he mostly nailed it, before adding…

"Whether DX-type keyboards will ever replace the often heavier-sounding analogue designs is open to question, and for a time it's possible that those who can afford it will want a DX as well as their Prophet or Juno, and not instead of.

"Only time will tell, but when the new Yamahas hit the market in quantity it's going to tell pretty quickly."

Time indeed did tell, as we shall see.

Finally, Paul Colbert in One Two Testing was as upbeat in November 1983, and the magazine even had a flexi-disc on the cover – remember those? – which had DX7 demo sounds on it.

It is a superb keyboard, but it does not spell death for the rest of the synth industry.

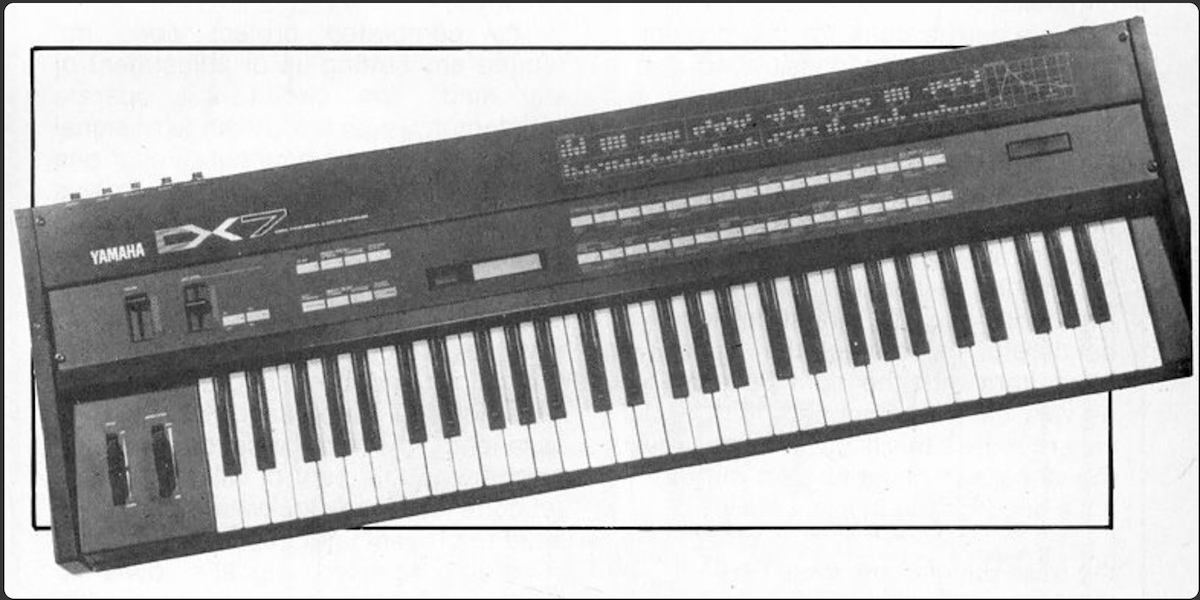

"It is one of the most important keyboard advances so far this decade," Paul correctly pointed out. "The real secret behind the DX series is that it produces noises like no other synthesizer in its price range – startling realistic acoustic voices, genuinely bizarre electronic tones and special effects which appear to have four things happening at once.

"It is a superb keyboard, but it does not spell death for the rest of the synth industry. Analogue polys still produce fabulous sounds that the DX is incapable of recreating."

Nearly correct, although as we will now see with the DX7's legacy, analogue consequently took a hell of a beating.

The DX7 was a hugely popular machine – the best selling synth of its time. You have to remember that, unlike today when synths are used in just about every genre of music, back in 1983 they were used for noodling German ambience or synth pop.

That meant that many synth users desired an expansion in that analogue sound and, before sampling, this usually meant wanting to make synths create 'real' sounds. The DX7 certainly fitted the bill.

Because the FM system produces complex waveshapes it is much better at simulating acoustic sounds.

As Mark Jenkins noted: "Because the FM system produces complex waveshapes it is much better at simulating acoustic sounds than an analogue synth could be."

And around 150,000 keyboard players bought into the DX7 concept. Roland answered with the D-50, Korg eventually with the M1 and analogue synths were pretty much wiped out, ending up in either skips or Vince Clarke's studio.

However, even though the likes of Brian Eno became huge fans, as he pointed out in this feature, the DX7 did have a problem: "It's funny; it's the single most popular contemporary synthesiser. Everybody has one. But nobody knows how to program them. They arrive with these factory-set sounds and that's all most people use. They never change those sounds."

Everybody has a DX7. But nobody knows how to program them.

Brian Eno

And he wasn't the only one to point this out, as it was something the original reviews had picked up on.

Dave Crombie pointed out the multi-function buttons and display that attempted to help: "There's a bank of 32 switches that adopt a variety of functions - some are used for up to four different jobs. A 32 character LCD provides a mass of programming data, and guides you through the programming and sound creation minefields."

Mark Jenkins noted: "The fact remains that keyboard players having just mastered analogue sound creation are now being asked to come to terms with a completely different method of playing and programming."

Keyboard players are now being asked to come to terms with a completely different method of playing and programming.

And finally, Paul Colbert concluded that, "the DX is totally different from an analogue synth. If you try to operate it to the same rules your head will dribble and you'll achieve only a fraction of the machine's capability. Idle fiddling is hopeless, you need to know where you're going. The complexity means spending a long time perfecting sounds."

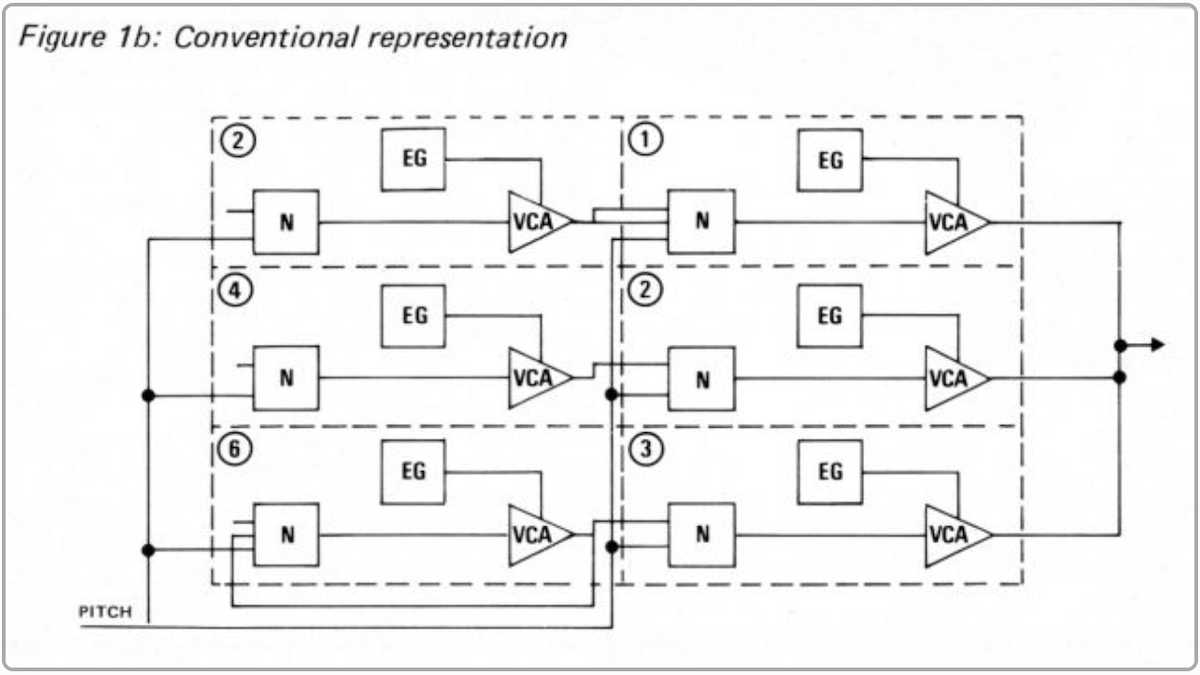

The fact is that FM synthesis is actually quite easy to get your head around – if you don't think about it too much, anyway. The problem with the DX7 was really about its deployment, burying the main parameters under those menus and pages of data. Newer synths add real-time controls for the main options, the Korg OpSix being a prime example.

It didn't help that magazines of the time published diagrams like this one to try and help with DX7 programmability.

Understandably, the programming side didn't take off. However, the presets did. The following likely use the DX7 to some extent or other and will give you a flavour of how widely it was used in the mid '80s.

Berlin's Take My Breath Away apparently used the 16 Bass 2 preset for 'that' bass sound…

a-ha's Take on Me again used a bass preset as this video demonstrates…

And here's the classic video for good measure.

And Whitney Houston loved the piano sound…

And here's the Twin Peaks theme (that piano again).

And, finally this classic used… well actually we don't know – probably the bass again – but we're including it anyway…

In fact the DX7 was used on a huge number of records in the mid '80s. Stat fans get ready. In 2019, Megan Lavengood, a then assistant professor of music theory at George Mason University, wrote a report called What Makes It Sound '80s?

While this report is worthy of a feature in itself, its DX7 highlight included the fact that, in 1986, preset E. Piano 1 was "present on 39% of the Billboard Hot 100 number one hit singles, 40% of the country number one hit singles and a staggering 61% of R&B hit singles".

As Megan says in her blog, "to say that the DX7’s arrival was earth-shaking would be no exaggeration".

Despite many DX variants (like the 100 above) coming out after the DX7, its sound was, as Megan concluded, very much of the '80s. By the '90s the Korg M1 had surpassed its digital power, and all of these digital machines would (eventually) be swept aside as dance music demanded the control and sounds of the early '80s, and few could be bothered with the digital menu-diving and multi-function keys.

Still, it's unlikely that a synth will ever have the impact – both positively and negatively – that the DX7 had, nor the sales. Today's machines, both analogue and digital, owe a huge debt of gratitude to the DX7, many still exploring its FM synthesis, albeit in easier ways, and most having the real-time controls it proved we all needed.

There are even quite a few with decent electric piano sounds.

And will a synth ever be used on 61% of the songs in any pop chart again? We doubt that very much.

There's a fabulous list of famous songs and their DX 7 preset use here – which we didn't use for this feature, honest – and thanks to Muzines for gathering those amazing old reviews on one place.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.

“Excels at unique modulated timbres, atonal drones and microtonal sequences that reinvent themselves each time you dare to touch the synth”: Soma Laboratories Lyra-4 review

e-instruments’ Slower is the laidback software instrument that could put your music on the fast track to success