"The worst track we ever had to record" – why 3/4 of the Beatles hated Maxwell's Silver Hammer

No Paul McCartney song ever incurred the joint wrath of Lennon, Harrison and Starr quite like Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. Here’s why…

Paul McCartney was behind the wheel of his blue 1964 Aston Martin DB5 when inspiration for one of The Beatles’ most whimsical and divisive songs struck. It was 10 January, 1966 and McCartney was driving from London to Liverpool and listening to a BBC radio play. It was an adaptation of a play called Ubu Cocu (Ubu Cuckolded), by French avant-garde writer Alfred Jarry. When Jarry’s play was first staged in Paris in 1896, it baffled and offended audiences. For McCartney, sixty years on, it was little short of a revelation.

“It was the best radio play I had ever heard in my life, and the best production,” he said in Barry Miles’ 1994 biography Many Years From Now. “And Ubu was so brilliantly played. It was just a sensation. That was one of the big things of the period for me.”

Alfred Jarry’s play would ultimately provide the inspiration for Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, the cheerful ditty about a homicidal hammer-wielding medical student, that would appear on The Beatles’ Abbey Road album. The track was McCartney’s nod to surrealism, a jaunty melody belying a deep, dark lyrical underbelly. The recording sessions for the track would become some of the most fraught and arduous in the history of The Beatles.

Six months later, McCartney and girlfriend Jane Asher went to see the play, when it was staged at the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square, London. McCartney was intrigued by the play’s reference to ‘pataphysics’ – a surrealist art and literary ‘science’ created by Jarry.

McCartney's friend, the aforementioned author Barry Miles, had been made a member of the so-called College of Pataphysics and awarded the Ordre de la Grande Gidouille for pataphysical activity.

“Miles and I often used to talk about the Pataphysical Society and the Chair of Applied Alcoholism,” said McCartney. “So I put that in… Maxwell’s Silver Hammer: ‘Joan was quizzical, studied pataphysical science in the home’. … I love those surreal little touches.”

According to liner notes by Kevin Howlett on the Super Deluxe Edition of The Beatles (White Album), McCartney wrote the first verse of the song in early 1968 while The Beatles studied transcendental meditation at the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh, northern India.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

I don't know why it was silver, it just sounded better than Maxwell's Hammer

Paul McCartney

In the book Many Years From Now, McCartney says the song epitomises the downfalls of life, describing the song as "my analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as it so often does, as I was beginning to find out at that time in my life. I wanted something symbolic of that, so to me, it was some fictitious character called Maxwell with a silver hammer. I don't know why it was silver, it just sounded better than Maxwell's Hammer."

McCartney first brought the song to The Beatles on 3 January 1969, during the Get Back/Let It Be rehearsal sessions. Peter Jackson’s 2021 documentary Get Back shows McCartney teaching the band the song, with Lennon and Harrison whistling the melody spontaneously. Further rehearsals took place on 7, 8 and 10 January.

It’s well documented that neither Lennon, Harrison or Starr liked the song and as rehearsals progressed and they ran through it again and again, their dislike intensified.

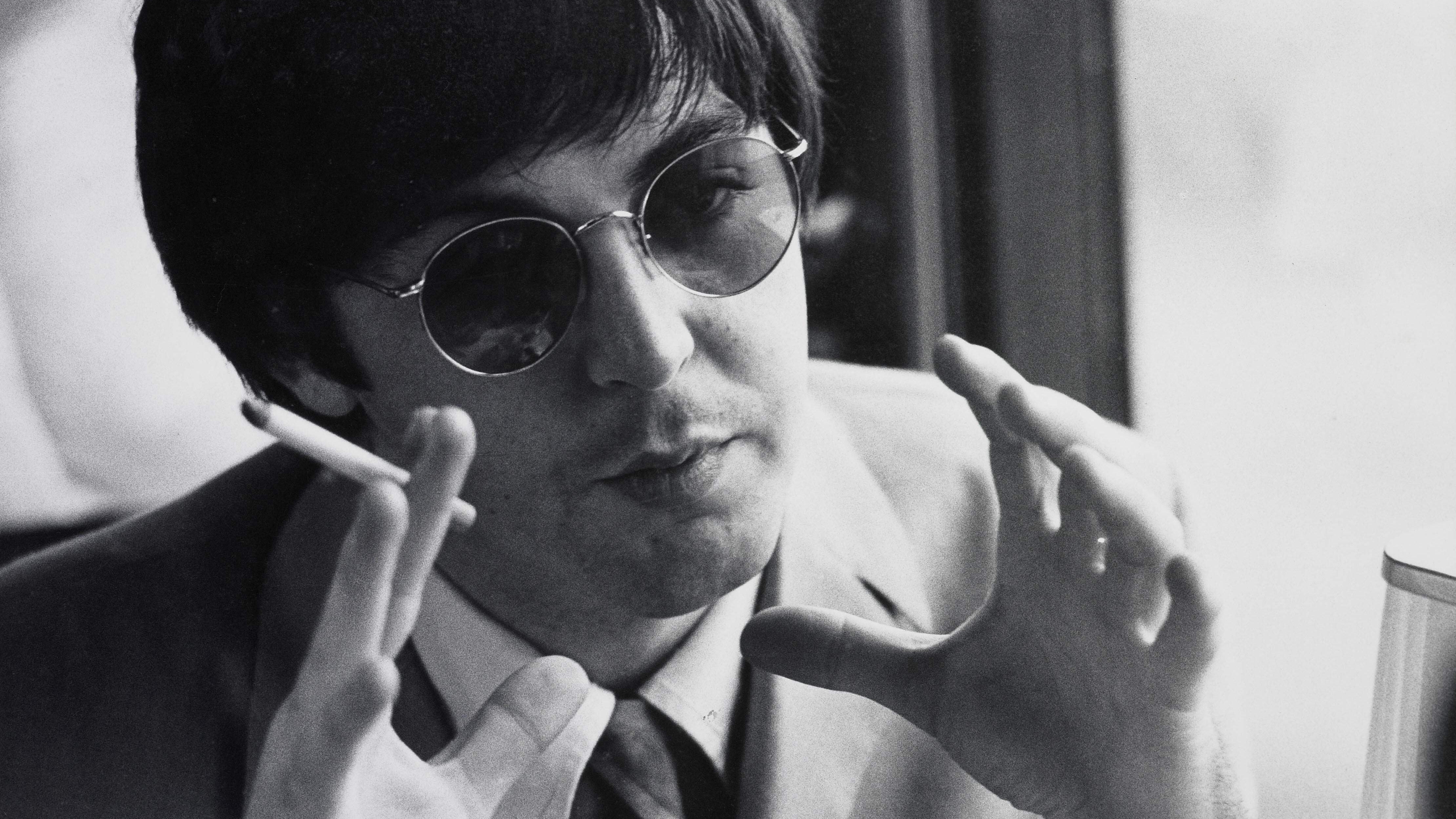

I hate it

John Lennon

"I hate it,” recalled John Lennon in an interview with Playboy in 1980. “He made us do it a hundred million times. He did everything to make it into a single and it never was and it never could've been… we spent more money on that song than any of them in the whole album."

Starr was equally blunt. "The worst session ever was Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” he said. “The worst track we ever had to record. It went on for f*****g weeks. I thought it was mad."

Sometimes, Paul would make us do these really fruity songs

George Harrison

George Harrison wasn’t in the studio on 10 January 1969, but by then, he too had tired of the track. “Sometimes, Paul would make us do these really fruity songs. I mean, my God, Maxwell's Silver Hammer was so fruity… We spent a hell of a lot of time on it. And it's one of those instant sort of whistle-along tunes, which some people will hate, and some people will really love it. It's more like Honey Pie you know, a fun sort of song. But it's pretty sick as well though, because the guy keeps killing everybody.”

Throughout the early rehearsals in early January 1969 one object provided a constant reminder of the increasing fractiousness surrounding the song: a large iron anvil in the centre of the recording area. Each time they ran through the song, their affable longstanding road manager and personal assistant Mal Evans took on percussion duties. Sitting cross-legged in a director’s chair, in front of the anvil, with a clipboard on his knee and grinning from ear to ear, Evan’s would dutifully hit the anvil with a large hammer on the first two beats of the bar in the chorus.

An ambulance brought Yoko in and she was lowered down onto the bed

It would be six months before the band actually recorded the song, at Studio Two at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios. Recording began on Wed 9 July 1969 and the session ran from 2:30 to 10:15pm. Eight days earlier, John Lennon and Yoko Ono had been involved in a car crash in Scotland and this was Lennon’s first session since the accident. That morning, as the studio technicians prepared the studio, there was an unexpected delivery.

“We were setting up the microphones for the session and this huge double-bed arrived,” recalled studio technician Martin Benge in Mark Lewisohn’s book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. “An ambulance brought Yoko in and she was lowered down onto the bed, we set up a microphone over her in case she wanted to participate and then we all carried on as before. We were saying, ‘Now we’ve seen it all, folks’.”

In Lewisohn’s book, engineer Phil McDonald recalls Paul, George and Ringo waiting for John and Yoko to arrive. McCartney, Harrison and Starr were down on the studio floor and anticipation was high. “They didn't know what state he would be in. There was a definite 'vibe'; they were almost afraid of Lennon before he arrived, because they didn't know what he would be like. I got the feeling that the three of them were a little bit scared of him. When he did come in it was a relief and they got together fairly well. John was a powerful figure, especially with Yoko – a double strength.”

The song was recorded as EMI’s Abbey Road Studios over four days, on 9, 10, 11 July and 6 August 1969. George Martin was once again in the producer’s chair while Phil McDonald was the engineer. As it turned out, Lennon never played on the recording of Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.

He flatly refused to participate at all in the making of Maxwell's Silver Hammer, which he derisively dismissed as 'just more of Paul's granny music'

“I was ill after the accident when they did most of that track, Maxwell's Silver Hammer,” explained Lennon. “And it really ground George and Ringo into the ground recording it, you know. I wasn't on Maxwell.”

In his autobiography Here, There And Everywhere, engineer Geoff Emerick recalls Lennon’s character at the time. “He was grouchy and moody, and he flatly refused to participate at all in the making of Maxwell's Silver Hammer, which he derisively dismissed as 'just more of Paul's granny music’.

Sixteen takes were recorded on the first day of recording, with McCartney on piano, George Harrison on a six-string Fender Bass IV and Ringo Starr on drums. The takes were numbered 1-21, although there were no takes 6-10. Take 21 was the one used and towards the end of the session acoustic guitars were overdubbed onto the last two choruses. Take 12 was included on some formats of the 50th anniversary reissue of Abbey Road.

On 6 August 1969, Harrison’s Moog synth was set up in Room 43 at Abbey Road Studios. The session was booked from 2:15pm to 11pm and it was McCartney who played the overdubbed solo part. The signal from the Moog was patched through from Room 43 to Studio Two.

“Paul used the Moog for the solo in Maxwell’s Silver Hammer but the notes were not from the keyboard,” said engineer Alan Parsons in Mark Lewisohn’s book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. “He did that with a continuous ribbon-slide thing, just moving his finger up and down on an endless ribbon. It’s very difficult to find the right notes, rather like a violin, but Paul picked it up straight away. He can pick up anything musical in a couple of days.”

While McCartney intended Maxwell’s Silver Hammer to appear on Let It Be, it was included on the Abbey Road album, which was released on 26 September, 1969. In a taped recording of a band meeting that same month, Lennon tells McCartney that none of the band “dug” Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, adding that it might be better if he gave songs of that kind to other artists. “I recorded it because I liked it,” responds McCartney.

Over the decades, the track has divided critics. In a 1969 review of Abbey Road, Rolling Stone journalist John Mendlesohn notes that "Paul McCartney and Ray Davies are the only two writers in rock and roll who could have written 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer', a jaunty vaudevillian/music-hallish celebration wherein Paul, in a rare naughty mood, celebrates the joys of being able to bash in the heads of anyone threatening to bring you down. Paul puts it across perfectly with the coyest imaginable choir-boy innocence.”

The song epitomises the downfalls of life

Paul McCartney

But other writers since then have not been as complimentary. In his acclaimed 1994 book, Revolution In The Head, author Ian MacDonald describes the song as a “ghastly miscalculation” and “by far his worst lapse of taste under the auspices of The Beatles”. MacDonald goes on to describe McCartney as “the immature egotist who frittered away the group's patience and solidarity on sniggering nonsense like this”.

In the 1994 project Anthology, McCartney sought to defend Maxwell's Silver Hammer. "Some of my songs are based on personal experience," he said. "But my style is to veil it. A lot of them are made up, like Maxwell's Silver Hammer, which is the kind of song I like to write. It's just a silly story about all these people I'd never met. ... The song epitomises the downfalls of life. Just when everything is going smoothly – bang! bang! – down comes Maxwell's silver hammer and ruins everything."

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track