Steve Vai tells the story of the Ibanez JEM

"I had no expectations. I thought I was just designing a guitar for myself"

Introduction

Back in 1987, an esoteric Japanese luthier and a frustrated LA virtuoso created the shred guitar that shook the world. Three decades later, Steve Vai explains why the Ibanez JEM “was just a killer machine”.

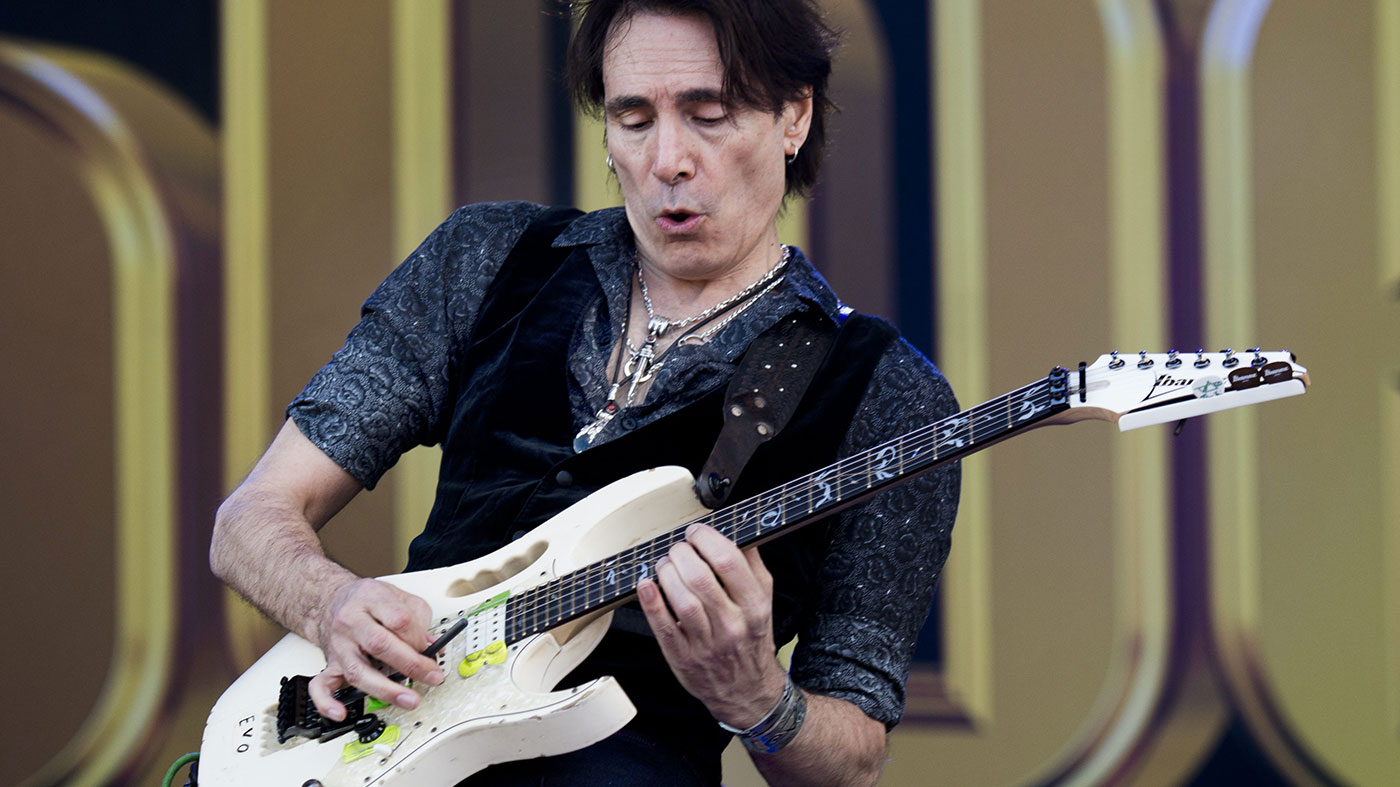

Backstage at Charleston Music Hall, South Carolina, Steve Vai is surveying a battle-scarred electric guitar. The instrument has plainly seen better days. The chipped white finish reveals the ravaged alder beneath. The neck has already been replaced twice.

This is Evo, the model that Vai fans will crane their necks for in an hour

Ostensibly, it’s an unlikely choice for Vai: a multi-platinum star whose website lists a 138-strong guitar collection. But to those who know, this is Evo, the model that Vai fans will crane their necks for in an hour, and the most famous member of the Ibanez JEM family. “It’s beat to shit,” Vai informs us, “but I’ll be playing it again tonight.”

If Evo’s lifespan is astonishing, so too is the apparent immortality of the JEM series. Thirty years have passed since news of Vai’s signature model raced through the 1987 NAMM show.

Over that same period, 1,000 vanity-project guitars have been created for transient rock stars, then discontinued when their fortunes faded. And yet, through every fashion and fad, the JEM has flourished, its lean double-cut styling, borderline-garish finishes and inimitable monkey grip now icons of the gear landscape.

“I’m stunned by it all,” says Vai of the model’s three-decade reign. “I had no expectations. It was very innocent. Back then, I thought I was just designing a guitar for myself.”

Zappa zip

Rewind to 1985, and Vai’s glittering career as sideman to David Lee Roth belied his frustration. Raised on the 70s rock heavyweights, he had tried to embrace the classic guitar designs.

Frank was innovative in virtually everything he did, and I saw how he would attack guitars, change necks, add electronics

“I knew I had to play a guitar with a whammy bar, but I didn’t like the way Strats sounded: it just didn’t seem rock ’n’ roll to me. And although I liked the humbuckers in the Les Paul, I wasn’t crazy about the way they were shaped. I stuck with the Strat all the way up to the Zappa years, basically.

“Frank was innovative in virtually everything he did, and I saw how he would attack guitars, change necks, add electronics. Then the Superstrats started to emerge with the likes of Edward [Van Halen]. And that’s when I realised that, y’know, you could have anything you wanted.”

Inspired, Vai headed to a Hollywood repair shop to breathe life into his fantasy spec sheet. “I wanted a 24-fret neck,” he reflects of the four resulting proto-JEM models. “This was rare at the time. The last four frets were scalloped, because, as Yngwie Malmsteen would say, you can really grab notes by the balls.

“I liked the Strat body, but it always looked kinda pedestrian, lacking some sexiness. So I put on more edges. And I couldn’t understand why conventional guitars never gave you clear access to the top frets. I made sure the cutaway perfectly fit my hand, so I could reach the 24th fret.”

Double whammy

By the mid-80s, with the shred scene at its lurid peak, the Floyd Rose was industry standard. Now, Vai hatched a bolder plan, born of exasperation that the dominant tremolo unit’s fine-tuners prohibited upward bends.

I took a hammer and a screwdriver, and I just banged down all the wood. Next thing I know, I have a floating tremolo system that was really floating

“I’ve always had a love affair with the whammy bar,” he explains. “But the Floyd wasn’t doing enough for me. Y’know, the Floyd had come along, and in the beginning, it wasn’t quite there. You could never pull up, just because the wood that the tailpiece rested on was in the way.

“So I took a hammer and a screwdriver, and I just banged down all the wood. Next thing I know, I have a floating tremolo system that was really floating. And they tell me this was the first one.”

The mix-and-match line-up of DiMarzios was another accidental revolution. “I was a PAF-head,” Vai recalls. “But I wanted to accomplish a sound with some bearing on what the Les Paul delivered, but also like a Strat’s in-between single coils, which was just a beautiful sound to me. So I came up with this design.

“I used the DiMarzio X2N on some of those original JEMs, with a five-way selector that split the humbuckers. For a guy like me, this was like, oh happy day. I was told later this was a unique pickup design. But none of that mattered to me. I just wanted a sound. And I got it.”

Tutti-frutti

Vai completed his original design with a few practical flourishes, removing one tone control, relocating the volume and angling the input jack (“because on Strats and Les Pauls, if you step on your cable, it comes out”).

It might have ended there. But with the guitar manufacturers of California clamouring for association with the Roth band, the guitarist sensed an opportunity.

They delivered me a guitar that was just perfect, within three weeks, exactly to my specs

“I always felt weird doing endorsements. And I had already made the [custom] guitar. But they were still interested. So I figured, ‘Well, if somebody can make these for me for free, why not? I know that it works for me, so maybe it’ll work for other people, too.’

“So I sent the design out to a bunch of companies that I probably shouldn’t mention. But all the majors, y’know? And what I got back was basically their guitar with a couple of tweaks. None of them were what I wanted.

“I was getting wined and dined, and I had to just tell these companies, ‘No, this isn’t it. It’s like I’m asking you for the colour red and you’re giving me tutti-frutti. Or actually, I’m asking for tutti-frutti and you’re giving me red.’”

Circa 1986, it was a stretch to describe Ibanez as a ‘major’. Established in the late 50s, the Japanese manufacturer was now attempting to shake off its reputation as a skilled purveyor of copies.

Heading up the American Artists Relations Centre, Rich Lasner earmarked Vai as a potential endorser, while resident timber expert Mace Bailey crafted a speculative guitar that anticipated the virtuoso’s tastes.

“That first model really had nothing to do with my design,” Vai recalls. “So I gave them my prototype and said, ‘No, make this guitar.’ And they did. They delivered me a guitar that was just perfect, within three weeks, exactly to my specs. That was the guitar. It was just a killer machine.”

All in the detail

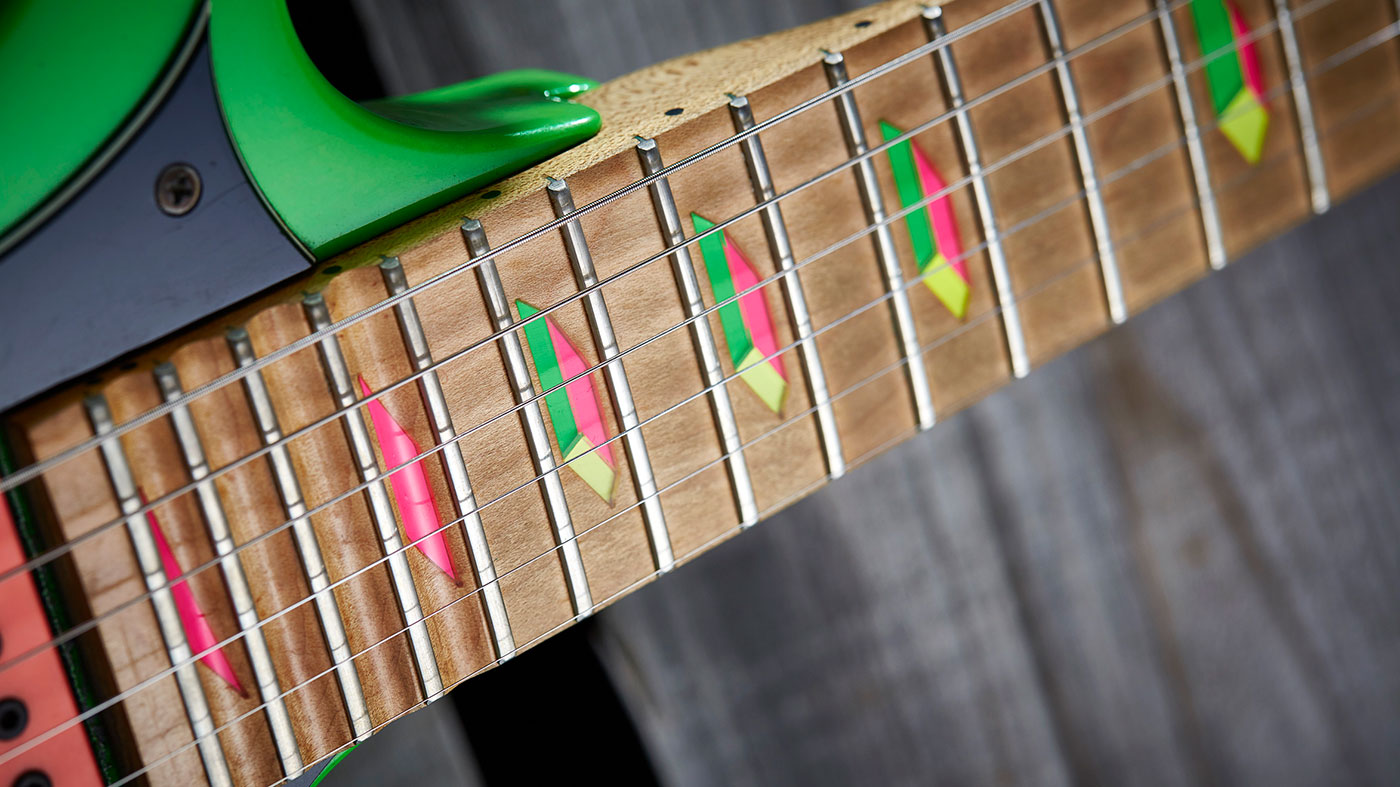

It was true: the original JEM 777 models were serious artillery. Finished in Loch Ness Green, Shocking Pink or Desert Sun Yellow, the body was constructed from a resonant US basswood that cut the weight down to 3.6kg.

The maple neck offered both speed and substance, with a 19mm depth at the nut and a slender feel that ensured seamless position shifts.

I decided to do one thing that no company would copy, because it would just be a blatant rip-off. So I put on the monkey grip

DiMarzio’s PAF Pros roared in neck and bridge positions, combined with a custom-wound single coil in the middle. The Ibanez Edge tremolo and lion’s claw recess represented a refined take on Vai’s crude carpentry, bolstered by stud lock posts and a push-in bar that didn’t spin maddeningly out of reach like its Strat forebear.

“The JEM,” nods Vai, “gained a reputation and a personality as being a shredder guitar. It was built for speed.”

Style was a factor, too. “I had an instinct,” reflects Vai, “that there were some very practical elements that would probably be borrowed by other companies once the JEM was a production model. But I decided to do one thing that no company would copy, because it would just be a blatant rip-off. So I put on the monkey grip.

“I also requested day-glo colours. So this went against everything that Ibanez was hoping for. They thought I was crazy. But I just thought, ‘Well, I have nothing to lose, I don’t care. This is what I want.’ And they did it. So this odd bird of a guitar came out…”

Back in NAMM

An instant hit upon its debut at NAMM in June 1987, perhaps it’s understandable that Vai has been reluctant to stray too far from the JEM’s winning blueprint.

I’ve considered, ‘What can I do to this guitar to change it?’” he reflects. “And really, the answer is, ‘Don’t f***ing touch it.’

“I’ve considered, ‘What can I do to this guitar to change it?’” he reflects. “And really, the answer is, ‘Don’t fucking touch it.’ It’s fine the way it is. It’s like, nobody’s sawing the horn off a Strat. This thing, it was born, and it is what it is, so I’m not gonna mess with it. I could, but I really don’t feel compelled to.”

In reality, the JEM has undergone a fistful of judicious tweaks since its inception. Most overt are the finish options, which span from the JEM2KDNA (featuring Vai’s own blood mixed with the paint) to the memorable floral-finish JEM77FP that launched in 1988.

“That pattern was actually some curtain fabric that I had,” reflects the guitarist. “We bought all there was in the world. And for some reason, that model for me is the best-sounding JEM. I think it’s some kind of mixture between the basswood and the fabric that creates this really tight sound.”

Evolution

More significant were the spec advances made to the JEM over the decades. “We switched to the All Access neck joint,” explains Vai, “and then we went to an alder body in 1993, with the white JEM7V, which is the longest-running model.

“The necks are much stronger, because now they’re five-piece maple/walnut with a volute. And y’know, the pickups change…” Indeed, while the earliest JEMs had featured stock DiMarzios, in 1993, Vai elected to create his own.

The pickups I designed as the JEM evolved were more compressed, not so many spikes, a little friendlier on the ear

“It wasn’t until the Evolution pickup came along that I started working with Larry [DiMarzio] on custom signature pickups,” he reflects. “In the 80s, you were always looking for the biggest, fattest, widest, warmest tone, because I was doing rhythm work behind a singer. That’s why things like PAFs worked well.

“But when I started to gravitate towards solo work, y’know, if you’re playing melodies and solos, you gotta be careful with the tone. So the pickups I designed as the JEM evolved were more compressed, not so many spikes, a little friendlier on the ear, a smoother top end. And I like a tight bottom end - who doesn’t?

“For the Evolution pickup,” he continues, “I had five white JEMs with five different sets of pickups. I couldn’t tell the guitars apart, they all looked identical. At the time, I had seven Harley-Davidsons - it was one of my explosions of freedom - so I named the pickups after various historical Harley engines and wrote the abbreviations on the bodies.

“The first one was the Flathead, so I wrote ‘Flatty’ on the guitar. Then there was the Knucklehead, the Panhead, the Shovelhead - and then the latest engine Harley had at the time, which was called the Evolution. And the guitar that I called Evo - which stood for Evolution - was the one I liked best. And that’s actually the guitar that I still play today. I’m looking at it right now.”

The theory of Evo

What’s so special about Evo? “Well, the magic in a guitar is based on the perspective of the player.

“Guitar players develop emotional attachments to an instrument. And then they create an identity for the instrument in their own head. And I’m very guilty of that.

Evo is not the easiest JEM to play and it’s not the best-sounding one, but there’s something about it that I’m just attracted to

“When I got Evo, it felt like the right guitar, so I started playing it. Now, I’m not a fan of new guitars. They feel weird to me. They don’t have my DNA in them yet. They need to be assimilated into your personality, and I just started doing that with Evo and developed a relationship with it as my go-to instrument.

“It’s like, I’ve been touring for 36 years, and I’ve slept in many different kinds of beds. Some of them were really comfortable, some of them were basically lounge chairs. But my bed at home is my favourite. It’s similar with Evo. It’s not the easiest JEM to play and it’s not the best-sounding one, but there’s something about it that I’m just attracted to.”

Practical psychology

Without the JEM, stresses Vai, he’d be a very different player.

“These guitars, I think it’s part psychological, but mostly it’s just practicality. The idiosyncrasies of my playing, I’m capable of them because of the way the JEM is built. And if you ever heard me play another guitar, if you know my playing, I’m out of my comfort zone, because I’ve just been so forensic with the JEM. I use it on virtually everything.

“On [latest album] Modern Primitive, there might be the occasional Les Paul or Strat, but really, when I’ve tried to do solos on other guitars, a lot of times, I just end up going back to the JEM.

Probably the best way to describe how I feel about it would be stunned and grateful

“There’s a bonus track on the 25th anniversary release of Passion And Warfare called Lovely Elixir. I did something very daring, at least for me, and I recorded that with a Gibson ES-330. And it was a fight.

“The JEM, to me, is like a smooth rollercoaster ride. And other guitars are like the Colossus - y’know, those old wooden rollercoasters where you’re lucky if you come out of it with your teeth?”

In the Charleston dressing room, Vai runs a hand over Evo as he attempts to sum up the JEM phenomenon. “Probably the best way to describe how I feel about it would be stunned and grateful,” he decides. “Y’know, the JEM has been a consistent seller for 30 years. We also made a lower-end version - the RG - and that’s gone on to be the metal guitar of choice.

“Just speaking pure numbers on a worldwide basis, the Strat is the biggest-selling guitar and then the second-biggest for many years has been a toss-up between the Les Paul and the RG. And then, some years after the JEM came out, I designed the seven-string Universe. And we all know what that ended up doing: it created a sub-culture.

“So the JEM was such a great project. And the fact that it’s so successful is just a stunner and a surprise and a delight…”

These guitars are from the collection of the late Jeff Pumfrett - many thanks to World Guitars for making them available.