The history of the Fuzz Face

Tracing the roots of the iconic pedal

Introduction

To mark the 50th anniversary of the humble but classic Fuzz Face, we take a look inside an original Arbiter model and talks with the pedal’s creators, plus Hendrix effects guru Roger Mayer, about how a mic-stand baseplate became the ace face…

It’s 1966, and Arbiter Electronics Ltd, captained by Ivor Arbiter - the man responsible for the ‘dropped-T’ Beatles logo and (for better or worse) unleashing karaoke onto Britain - introduces the world of music to its newest arrival, the Fuzz Face: “Fuzz Face is the new fuzz box from Arbiter giving the ultimate in controlled effects,” the sales blurb of the time enthused.

Arbiter used the bottom of a microphone stand to fit the circuit board in, and that is how the round shape came about

“Whilst the new design angle of Fuzz Face is both attractive and amusing, without doubt the keynote of the unit is to be found in its functional construction and operational success… and at the recommended retail price of 8gns is certainly Top Value! The Unit is finished in Red, Black or Hammered Silver.”

Certainly radical, nothing before had ever resembled the Fuzz Face. It was something of a spectacle to behold among the generally plain, boxy designs of other effects pedals on the market at the time. With its cartoonlike appearance, this thing had personality!

Denis Cornell, a renowned electronics engineer who now creates his own range of effects and amplifiers, used to test early spec Fuzz Faces in the factory before they were boxed and shipped out across the country. He recalls Ivor Arbiter telling him the story of how he invented the design: “He used the bottom of a microphone stand to fit the circuit board in, and that is how the round shape came about,” Denis told us.

Despite the smiling visage, however, just what mood the pedal was in could change virtually in an instant. The original components in the circuit were quite unstable, often with wide tolerances, meaning that no two Fuzz Faces ever sounded the same.

In fact, the same Fuzz Face would often be prone to radical changes in tone based on simple factors such as ambient temperature, particularly when fitted with the NKT275 transistors used in the very first units.

These vagaries were all down to the nature and quality of the components used in its design - a design that was stunningly simple: the circuit employed only two transistors, three capacitors and four resistors, along with the potentiometers (or ‘knobs’ in layman’s terms), meaning it was impossible to patent, being a standard in engineering textbooks.

Voodoo smile

Jimi Hendrix is arguably the most famous Fuzz Face devotee and played a major part in its continued popularity. Roger Mayer, Jimi Hendrix’s all-round tone guru, is therefore no stranger to the pedal, as it was Jimi’s fuzz pedal of choice - mainly for live use, but also in the studio, though it would have to be carefully fettled for recording.

At first, testing these units was a nightmare - each unit having different output levels, I seemed to be forever changing transistors

“The term ‘Fuzz Face’ is really a trade name to describe the enclosure,” Roger argues. “What is actually inside the enclosure electronically has gone through several evolutions. But, essentially, a transistor is a three-terminal device. There’s not many ways you can connect up three terminals, is there? Most of the elements of the circuit can be seen in any textbook from 1965. They’re all written down. You couldn’t patent it. It’s impossible to patent an obvious way of connecting up two transistors.”

Despite this core simplicity, Denis Cornell recalls the difficulties endured when factory-testing Fuzz Faces: “At first, testing these units was a nightmare - each unit having different output levels, I seemed to be forever changing transistors to find some kind of common ground. Characteristics of the transistors meant that normal testing by voltage signal and oscilloscope did not pick up the variations in performance. In fact, I hated the job and dreaded when a production run was requested.

“However, I soon added a ‘guitar test’ to the test procedure. In fact, this was the only way to test the unit. I soon discovered a technique for knowing what was good. For example, striking a note and listening to the decay: poor units would die away quickly and lose the tone. Also, playing high notes, due to their less high output - the high notes were diminished and would decay faster. Finding a good one was a dream, and the guitar would sustain forever.”

This very simple circuit: yes, it worked, but maybe only one out of 20 worked well

The potential for magical tone was there for sure, albeit quite often hard to find, as Roger confirms: “They weren’t consistent, so when I first heard one I said to Jimi, ‘Let me take one back to the lab and have a look at it and analyse what’s going on in the circuit.’ It became apparent without very much analysis that it is what one would call a ‘minimum-parts circuit’.

“In other words, there were a lot of shortcuts taken to minimise the amount of components. It would work, but it didn’t take into account any of the other ‘accepted’ electronic techniques being used. I was working for the government at the time in vibration and acoustic analysis - and the Fuzz Face didn’t take into account any of the pitfalls. So, this very simple circuit: yes, it worked, but maybe only one out of 20 worked well.

“The fact of the matter was that not only did you have a circuit that was simple to the point of instability, no provision was made in the early days for the huge variance in performance of the pedal’s components - especially the transistors. Back then, you had commercial components that could test at 10 to 20 per cent above or below the values they were supposed to have (and that was just for the resistors). The capacitors might test at minus 20 per cent to plus 50 per cent. The crucial transistors could also vary a lot, especially in the amount of gain they produced. So, you never had two early Fuzz Faces that sounded the same.”

The colour of sound

Nevertheless, Jimi continued to use a Fuzz Face regularly in the recording studio, although it was often through Roger’s intricate knowledge of electronics and the close, personal understanding of Hendrix’s musical vision that yielded successful results, as Roger explains.

“Jimi and I were back at the flat and playing with some sounds for a particular cut - we’d have a vision about what the song was about. Now, when I say ‘vision’, that is the correct word. Jimi and I had a synaesthesia - a correlation of colour and sound and images… The experimentation and knowing how you could manipulate the circuit and also the tricks you could employ in the studio, it’s continuous.

Jimi Hendrix had 15 or 20 of them and he used to lose three or four a week!

“I would be standing with Jimi in front of the amplifiers, because we didn’t use one amplifier - we’d use two or three different ones and sometimes a direct signal path into the console. The sound was blended, by which I mean it wasn’t just a Marshall amplifier; it wasn’t just a Fender, or Sound City… and we had different microphone placements. But I then had various other circuits that we put in front of the Fuzz Face to buffer them and provide pre-equalisation to the Fuzz Face and after it as well, before it went into the amplifier.”

Although the Fuzz Face remained an invaluable studio tool, Roger soon developed other bespoke effects, although Jimi’s use of the Fuzz Face became a mainstay on the road, as he points out.

“Working with Jimi, straight away within two months I developed my own new fuzz boxes for Jimi that were superior in every way to a Fuzz Face. They weren’t as cheap to make. You couldn’t go and buy 20 of them down the road for £6 each. So, the boxes I made for Jimi, he didn’t want to lose, so we only took out commercial ones on the gigs. Then we didn’t worry if they were stolen. We had 15 or 20 of them and we used to lose three or four a week!”

So, the question remains: what is it exactly that defines a really good early Fuzz Face, as opposed to a temperamental tonesucker? What is this voodoo? People swear by them! Jimi Hendrix certainly isn’t the only major name in music to inadvertently endorse (in fact, some actively endorse) the pedal: Eric Johnson, Joe Bonamassa, David Gilmour, Duane Allman, Pete Townshend and George Harrison - all famous and all are famously associated with, to some degree or other, the Fuzz Face.

There are what you might call ‘Fuzz Face Experts’ out there who have, over the years - through painstaking trial and error, as well as rigorous scientific analysis - brought us closer to the secret of nailing that elusive magic within a brilliantly simple electronic circuit to give you the dream tone.

One such expert is Mike Piera of AnalogMan, a specialist in reproducing classic effects - with the benefit of modern experience and technical insight, not to mention access to components of far greater quality than the mixed bag of yesteryear’s factory parts.

Transistor tone

In Mike’s view, transistors are the core ingredients in getting great tone from a Fuzz Face. As Mike states:

“If you start with bad-sounding transistors, nothing can help. Good ones will allow a lot of harmonic content - just scratching the strings can usually tell me if the transistors are worth using or not.

If you start with bad-sounding transistors, nothing can help. Good ones will allow a lot of harmonic content

“After that, tuning the transistors’ bias and choosing the right capacitors should make the pedal sound right. The values of the resistors are extremely important, for biasing the transistors to keep them in their happy range, and also to set the level of the output.

“I like to use carbon-composition resistors as they are a bit warmer sounding,” he continues. “But there is little difference in sound as long as high-quality parts are used. With regards to the capacitors, it’s the values that are most important. I like to use the shiny blue Philips capacitors for the two large values, as that’s what was used in the originals, and they sound great. For the output cap, I like to use similar types to the originals, too - some Mullard or Philips film capacitors. We use the flat yellow Philips in some versions, just like the originals.”

There continues to be hot debate about the use of the most coveted of all Fuzz Face transistors, the NKT275 germanium transistor (used in the very first units made between 1966 and 1968) and the silicon transistors installed thereafter. As Mike points out:

“Germanium tends to be warmer with lower gain and noise. And the feature that many people love about the germanium transistors is how nicely they clean up when you roll your guitar down. You can actually get a cleaner sound than ‘off’ in some situations - like into a cranked Marshall.

“Silicon tends to get a little brittle and bright when you turn the guitar down. The main problem with germanium is the temperature sensitivity. No matter what you do with bias and tricks to keep the transistors operating well, germanium just sounds bad when it gets too hot.”

As a matter of interest, that last point is born out by the fact that some top studios keep their vintage Fuzz Faces in a fridge before use, for that very reason.

And what of the future for the Fuzz Face? As long as people keep coming back to those classic rock tones, then our love for them will never die. That sound is so ingrained in our musical palette that it would be hard to imagine a world of music without them. Long live the Fuzz Face! Keep on rocking. Keep on smiling.

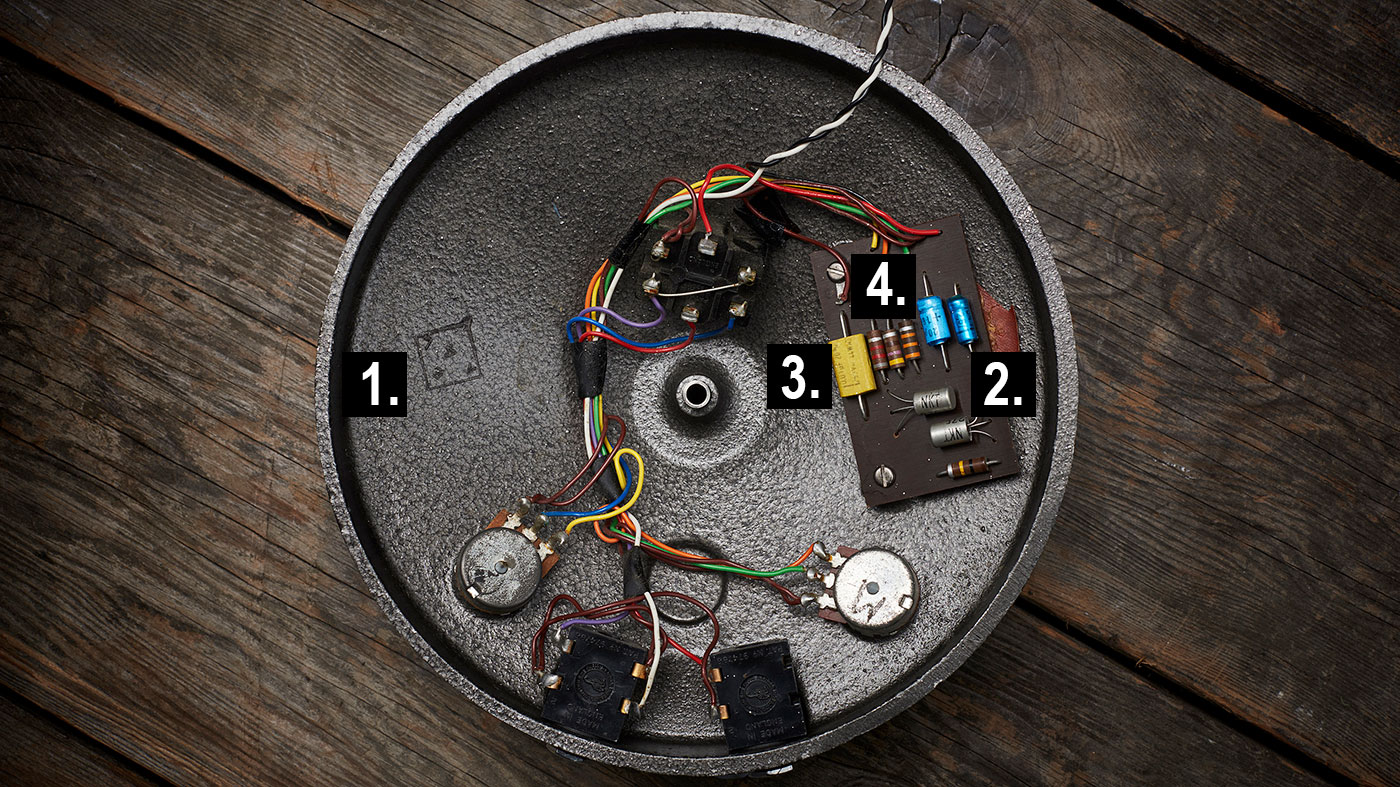

Inside the Fuzz Face

1. Enclosure

The famous circular enclosure of the Fuzz Face was the brainchild of Ivor Arbiter.

2. NKT275 transistor

Famously great-sounding (but infamously fickle), the Newmarket or NKT275 germanium transistor was soon replaced by silicon units that could be made to more predictable tolerances, though the sound changed, too.

3. Flat yellow Philips capacitor

Flat yellow Philips capacitor - these are used in some modern re-creations of the Fuzz Face, including pedals made by Mike Piera of Analog Man.

4. Striped resistors

The Fuzz Face’s striped complement of resistors. Quality modern recreations of early Fuzz Faces may use carbon-composite resistors.

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.