"It’s a common misconception among the unconverted that the Grateful Dead’s music was characterised by aimless noodling, rather than by deftly deployed fretboard know-how": 5 songs guitarists need to hear by the Grateful Dead

Best of 2024: Newcomers can dig in for a long strange trip here

Join us for our traditional look back at the news and features that floated your boat this year.

Best of 2024: Formed in Palo Alto, California in 1965, the Grateful Dead are remembered for a great many things: for their counter-cultural tendencies and enthusiasm for mind-expanding drugs; for their jammed-out live performances and the “long strange trip” that lasted 30 years and saw them rank as one of the highest grossing touring acts in US history; for having only one single from their 13 studio albums make a dent in the in Billboard top 40; for their ‘Wall Of Sound’ live speaker rig and permissive stance on bootleg recordings; for their dedicated ‘Deadhead’ following and for a legacy of tie-dye t-shirts, dancing bear bumper stickers and a signature flavour of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream.

But it’s the magical six-string partnership of Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir that we’re here to celebrate in this list of five essential Grateful Dead tracks that every guitarist must listen to.

If you like what you hear, you’ll be delighted to find that this list represents a mere 1.1% of the Grateful Dead’s enormous repertoire of around 450 songs (including covers), and there are countless live variations and fan-recorded tapes to dig through to your heart’s content. The Grateful Dead, after all, were a band who prided themselves on avoiding playing any given song quite the same way twice.

Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir met for the first time on New Year’s Eve in 1963. The pair jammed, hit it off and went on to form an ensemble called Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions – an old-time-flavoured predecessor to the Dead in which Garcia played guitar, banjo and kazoo, and Weir handled secondary guitar duties as well as washtub bass, and – yep, you guessed it – a jug.

Then, seduced by The Beatles and other British Invasion bands who were touting electric instruments, Mother McCree’s morphed into a much harder rocking outfit called The Warlocks – also featuring Phil Lesh on bass and Bill Kreutzman on drums – which then evolved once more to become the Grateful Dead.

Together they traversed far-flung corners of the musical universe, picking and choosing traits from bluegrass, blues, rock, folk, country, jazz, funk and even a hint of reggae to infuse their sound along the way. Of course, Garcia’s lead guitar playing has been most thoroughly championed, but Weir was – and is – no ordinary rhythm player either.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The pair’s three decade-long partnership came to an end with the untimely death of Jerry Garcia in 1995, but Weir has been keeping the music alive in Grateful Dead-adjacent outfits since the late 1990s – the most recent and notable of which, Dead & Company, features John Mayer in the Jerry Garcia role.

Dead & Company recently announced that they’ll be hanging up their touring shoes after one last summer road trip in 2023, so if you need to brush up on some GD genius before piling into a van and following suit, this list is a fine place to start…

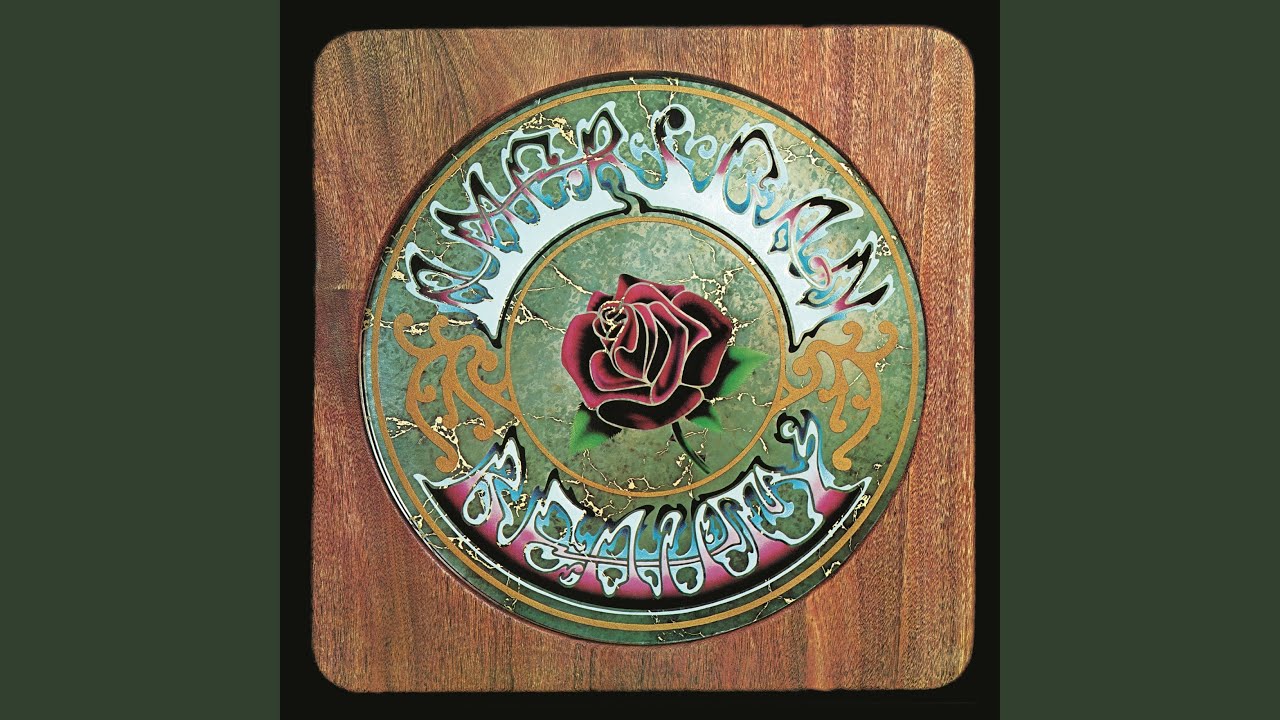

1. Candyman – American Beauty (1970)

Co-written by Jerry Garcia and long term lyrical collaborator Robert Hunter, Candyman made its debut during a mid-show acoustic set at the University of Cincinnati in 1970. Six months or so later, it joined nine other tunes of similarly folk and country-leaning tendencies - including Friend Of The Devil, Truckin' and Ripple - on American Beauty. The album would become one of the band’s most universally celebrated studio efforts.

Atypically violent in mood for these purveyors of peace and love, the line “If I had me a shotgun, I’d blow you straight to hell,” became notorious for getting cheers during live performances, much to the dismay of Hunter. But, from a guitarist’s perspective, there are a couple of factors that make this ode to the travelling gigolo a real winner.

The first is Garcia’s wonderfully off-kilter intro lick that gives a trippy twist to a staple from every traditional country guitarist’s bag of tricks: sweet, sweet parallel sixths. Taking familiar sounds from American musical traditions and freaking with them just a little bit is what American Beauty is all about, and here, the notes themselves feel comfortingly familiar, but the bright, brittle and - for want of a more technical term - wonky guitar tone is unsettling, and that’s what makes it really interesting.

Following its release in 1975, Garcia became fond of the MXR Phase 100 pedal, and began using it all over live performances of Candyman - thus imbuing the track with yet more psychedelic personality.

Secondly, Garcia busts out a stunningly ethereal pedal steel solo mid-way through Candyman, showing off his natural talent for a devilishly complex instrument that takes most people years to master. At the time of recording, Garcia had been teaching himself the ‘steel for just over a year, and had already lent his skills to Crosby, Stills & Nash on the classic song, Teach Your Children.

During live performances, Jerry played regular guitar solos, rather than pedal steel, so ‘Candyman’ offers a rare example of a Grateful Dead studio capture that was simply never bettered in a live setting.

2. Playing In The Band – from Grateful Dead (Skull & Roses) [Live] (1971)

No song epitomises the jam band spirit quite like Playing In The Band. Co-credited to Bob Weir, Robert Hunter and Mickey Hart, the song evolved out of an instrumental jam called The Main Ten, and gets its unusual, slightly untethered feel from its 10/4 time signature.

Following its initial release on the 1971 Skull & Roses live album, Playing In The Band became a pillar of Grateful Dead live sets, getting a total of 581 on-stage outings, and serving as a major vehicle for extended improvised workouts.

But, clocking in at just over four and a half minutes, the original Skull & Roses version is tight and compact, compared with most later evolutions of the song, which typically ranged from 10 to 20 minutes in length.

The longest known version was captured in 1974 at Hec Edmundson Pavilion in Seattle, where the band indulged in an extra-long jazz-infused and wah wah pedal-enriched psychedelic improv marathon for around 40 minutes, before wrapping up the epic adventure with one last perfectly cued blast of the song’s catchy chorus.

While it's easy to focus on Garcia's lead playing in these jam sections, Bob Weir’s underlying use of tasty chord voicings and inversions designed to influence the harmonic direction of travel is equally noteworthy. He admired jazz pianists like McCoy Tyner, who played for John Coltrane in his Quartet, and in an AXS TV interview with Dan Rather, Weir notes how he was inspired by Tyner “taking a lead in his own way,” despite not occupying the lead role in the band.

He explains: “He was finding direction - new direction - every time he sat down at the piano. Finding new places to take the harmonic structure of the song they were playing. So, very quickly, I figured out that’s what I want to be up to.”

3. Help On The Way / Slipknot! / Franklin’s Tower – Blues For Allah (1975)

Please excuse us while we bend the rules with this entry because, quite clearly, this isn’t one song. But, this trio of tunes goes together like tequila, lemon and salt, peanut butter, jelly and sliced white bread - or any other classic combination of three things you care to think of.

Not only do they run in sequence on 1975’s Blues For Allah studio recording, but they were more often than not performed live together, with Slipknot! acting as an instrumental segue between the mind-mangling minor groove of Help On The Way and the much more upbeat Mixolydian-hued stylings of Franklin's Tower.

It’s a common misconception among the unconverted that the Grateful Dead’s music was characterised by aimless noodling, rather than by deftly deployed fretboard know-how. So, if you’re in any need of evidence to convince you of the latter, listen to Jerry’s lead playing across this complex suite of songs.

For example, just beyond the three-minute mark (on the studio version) of Help On The Way, you’ll hear him flying through a whirlwind of precisely executed minor arpeggio and diminished scale-based licks that follow (or perhaps lead) a rapidly shifting base of chord changes and key modulations performed by Bob Weir and Phil Lesh.

Without getting too bogged down in the mechanics of it all, the fact is that Garcia knew what he was doing; he wasn’t a “one scale fits all” kind of guy, and there was nothing accidental about his navigation of the fretboard. He and the band had well and truly opened their minds to the consciousness-expanding drug of jazz theory.

A fan of players like Al Di Meola and George Benson, Garcia’s delivery of the solo sections in these tunes also carries much more of a jazz feel than a rock or blues one. He doesn’t opt for muscular bends or excessive vibrato, and doesn’t flex with any large left hand stretches or quantum leaps from one end of the neck to the other.

Rather he works his way up, down and around the neck via a comfortably interconnected network of scale shapes that follow the underlying chords - often landing on the chord tones (the individual notes that make up any given chord) at the pivotal moments of change.

Shakedown Street – Shakedown Street (1978)

By the time Shakedown Street was released in 1978, the counter-cultural hippiedom of the sixties was a distant memory, LSD had long since been outlawed, and sonic inspiration for the album’s title track came from a much more unlikely place: percussionist Mickey Hart’s interest in the disco-pop stylings of The Bee Gees.

Tight, succinct and full of brilliantly syncopated rhythmic interplay between Garcia, Weir and Lesh, Shakedown Street saw the Grateful Dead get dead funky.

![Grateful Dead [4k50p Remaster] - Shakedown Street - 1981 03 28 (pro shot) Rockpalast Germany - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/0CgM6s1LLuY/maxresdefault.jpg)

Gear innovations – particularly in modulation effects – had kicked up a notch or two in the 1970s, giving artists a much greater array of expressive tools to add to their pedalboards. This track is infused with extra funk power by way of lots of liberal usage of another Garcia favourite: the Mu-Tron III envelope filter.

With the intensity of its quacky intergalactic weirdness being directly proportional to the amount of attack imparted to the strings, Garcia could be as tasteful or as bold with the Mu-Tron III as he felt on any given night. Similarly, there were plenty of occasions where the band would also opt to subdue the bombastic disco pace of the studio version and swing ‘Shakedown Street’ with a slower and more relaxed R&B-type groove live on stage - it all depended on their mood and the direction of the set.

The instantly recognisable auto-wah sound of the Mu-Tron III can also be found all over the laid-back slink of Fire On The Mountain and the reggae-tinged Estimated Prophet.

Fun fact: Shakedown Street was produced by Little Feat’s Lowell George – a man who knew a thing or two about groove – but despite this and despite stylistic nods to contemporary chart-toppers, the single itself failed to chart.

5. Althea – Go To Heaven (1980)

Although Go To Heaven as a whole was met with middling-to-poor reviews when it was released in 1980, Althea is an undisputed gem of a tune, and it makes for a great gateway into the Deadzone for those less familiar with the band’s more dauntingly freeform material.

Current Dead & Company member John Mayer even credits it as being the song that first caught his ear and turned him on to the band back in 2011, when he stumbled across it while listening to random suggestions on Pandora.

With its lazy, relaxed groove and layers of moving guitar parts, Althea is a shining example of the fluid push-and-pull relationship that Garcia and Weir had with each other and with the beat.

It’s stuffed with neat little chromatic walk-ups, tasty suspensions and embellishments of simple chords and some ingenious slide flourishes from Weir.

As with all Grateful Dead songs, the studio recording of ‘Althea’ differs greatly from live performances, and two stand-out versions well worth seeking out include those recorded at Nassau Coliseum in 1980, and for the German music TV show Rockplast in 1981, during which Garcia extracts some stunningly idiosyncratic tones from his iconic Doug Irwin-designed Tiger guitar.

Tiger sports the highly unusual configuration of having a pair of humbuckers in its bridge and middle positions and a Strat-style single coil in the neck position. With a five-way selector switch, two separate tone controls and coil-cut toggles for the bridge and middle pickups, the guitar gave Garcia a fine array of fully customisable tones right at his fingertips.

A reasonable at-home hack for getting somewhere in the right ballpark of the Althea tone is to whack your selector switch between two pickups and experiment with rolling off the tone controls until you hit that throaty-bordering-on-nasal sweet spot.

Ellie started dabbling with guitars around the age of seven, then started writing about them roughly two decades later. She has a particular fascination with alternate tunings, is forever hunting for the perfect slide for the smaller-handed guitarist, and derives a sadistic pleasure from bothering her drummer mates with a preference for “f**king wonky” time signatures.

As well as freelancing for MusicRadar, Total Guitar and GuitarWorld.com, she’s an events marketing pro and one of the Directors of a community-owned venue in Bath, UK.

“Instead of labouring over a perfect recreation, we decided to make an expanded counterpart”: Chase Bliss teams up with Mike Piera for Analog Man collab based on the legendary King Of Tone

“It’s about delivering the most in-demand mods straight from the factory”: Fender hot-rods itself as the Player II Modified Series rolls out the upgrades – and it got IDLES to demo them

![Grateful Dead - Touch Of Grey (Official Music Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/mzvk0fWtCs0/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Grateful Dead [4k Remaster] Playing in the Band - Winterland 1974 - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/rvk0beSlydo/maxresdefault.jpg)