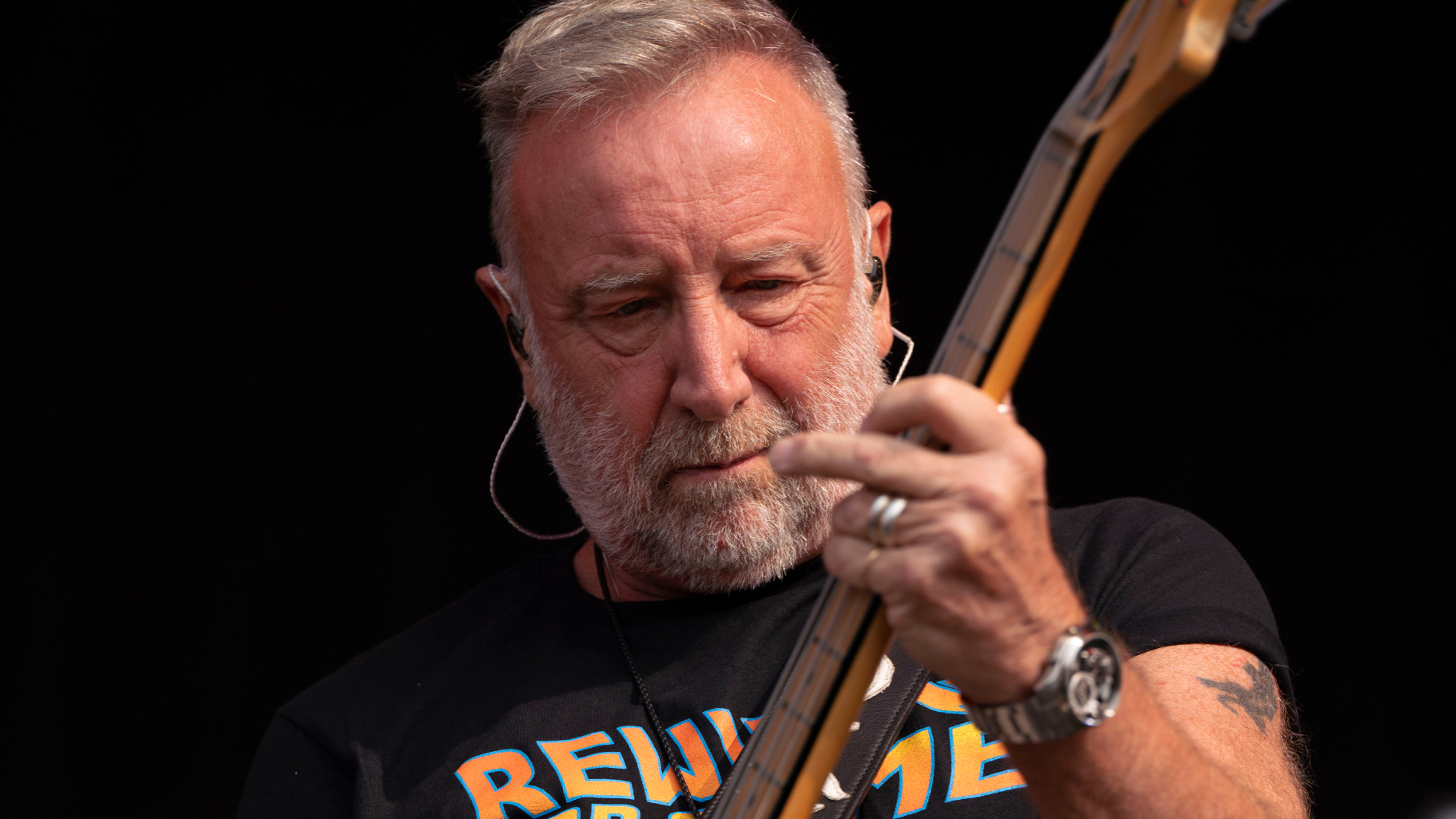

The Cult’s Jamie Stewart: “The job of a bass player is not to be front and centre; it’s to play your part in the bigger sonic picture”

Looking back on the band's '80s peak

The Cult were and remain that rare thing, a band whose appeal extends across multiple generations of music fans. Back in the early to mid-'80s, the London/Manchester band - singer Ian Astbury, guitarist Billy Duffy, bassist Jamie Stewart and a succession of studio and touring drummers - were variously labelled by the press as a post-punk act, as goths, as a heavy metal group and permutations thereof, each of which was at least partly correct.

Stewart, who was with the band from its formation as Death Cult in 1983 and left in 1990, was on board for the quartet’s most celebrated period, recording four landmark albums and touring with huge bands such as Metallica and Guns N’ Roses. Not long after his departure, grunge arrived and the Cult’s brand of Led Zeppelin and AC/DC-influenced hard rock was rendered obsolete virtually overnight. Good timing, that man.

When you’re trying to assemble music sonically, you figure out what a bass player is supposed to do

While it should be pointed out that Astbury and Duffy have continued to tour and record fine music with new line-ups since then, their most recent career high points have come when two of their albums - Love (1984) and Electric (1987) - were celebrated with 25th anniversary tours in the last decade. Their fourth album from this golden era, 1989’s Sonic Temple, didn’t get the same treatment, but with its 30th anniversary coming next year, who knows?

Now a stalwart in the software industry, Stewart has spent the last quarter-century out of the public eye, but thanks to the gift of social media, we requested an interview and duly took him to the pub…

How did you get started on bass, Jamie?

“I started as a guitarist, and I never really considered myself a bass player, just a member of a band. I only really learned how to be a bass player after I left the Cult and became a producer. When you’re trying to assemble music sonically, you figure out what a bass player is supposed to do. I was influenced by Tony Visconti on David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold The World album, because his bass playing is extraordinary. There’s a part where Visconti stops in mid-song and goes for a fag. It’s staggering.”

What was your first band?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I was in a post-punk sort of goth band called Ritual when I was 16, in north London. We released a couple of independent singles around 1981. Ritual’s drummer got poached by Ian and Billy, who were looking to form a band, and he recommended me as a bass player - even though I’d barely played bass, other than a bit of faffing about. I went to my local music shop in Harrow and asked if I could borrow a bass for an audition. It was one of those no-name copies with black nylon strings. I hacked through a few songs and they offered me the gig, so I bought a Rickenbacker 4001. That was my first proper bass.”

Precision and picking

Why that bass? The Cult’s style wasn’t obviously suitable for a Ricky.

“It was partly because the bass player in Billy’s old band, Theatre Of Hate, had used one, and therefore the 4001 was a known quantity; we knew what it could do. Image and character were important in a band like the Cult, so playing a no-name bass wouldn’t have worked. Later I graduated to a Music Man Stingray, which was cool, with a nice sound, and someone gave me a Tokai Hard Puncher when we were in Japan. Uncool though that may appear, it actually sounded really good, certainly for live stuff.”

You played a Fender Precision for some years, didn’t you?

Learned how to groove through trial and error. Until the Love album, we were part of a scene where bass players did quite a lot of playing

“Yes, but it wasn’t mine. Billy picked up a 1961 white Precision, which had the sound that only good Precisions have, and he lent it to me occasionally, so you’ll see it in videos and so on throughout the Cult’s history, along with a Precision that I owned. Still, because I was a punk kind of guy and played it low down, the fat neck was a bit of a challenge, so I discovered that I preferred Jazz basses, which sound similar. I think mine was a ’67, and I toured with that for a long time.”

You had some pretty inventive bass parts on the early Cult singles and the first album, Dreamtime.

“I guess so! I learned how to groove through trial and error. Until the Love album, we were part of a scene where bass players did quite a lot of playing. The bass player is pretty prominent in Theatre Of Hate, for instance; he’s up in the mix and the songs are built around bass-lines. The same went for the Cult; there was a lot of double-string stuff going on.

“For example, the song Spiritwalker is in G, so I played a G on the fifth fret of the D string alongside the open G string, just because it sounded cool and it gave me more oomph. Some of those songs have bass that is all over the shop. There’s no slap bass, but I did pop a bit, because it sounded interesting and different, like on Ressurection [sic] Joe, which was built around a bass-line. It was a steep learning curve.”

Which album do you think has matured best?

“Love was the most groundbreaking one I did, for sure. The single She Sells Sanctuary was a big hit in the middle of 1985, and then all of a sudden we were selling out bigger places. Before that we played a lot of clubs and universities. Steve Brown, who produced Sanctuary, told me when I was plucking away with a pick that it sounded pretty flat and needed some character. So I developed a more groovy thing for Rain, which was the next single.”

Economy playing

A load of Cult songs - Sanctuary, Rain, Lil Devil, Love Removal Machine and more - are basically just D, C, G. Given that, did you ever tune down so you could play the D on your E string?

“Yes, I got a Hipshot detuner after Love because we wanted to get a low D. It was a bit confusing live, but it worked. I couldn’t buy a five-string, because that was viewed as uncool, haha!”

There’s a sub-bass D note in the middle of Sanctuary. How did you do that?

“I didn’t have a detuner at the time, so perhaps I tuned down in the studio. Live, I just played a regular D note. You probably know that the Electric album was recorded twice? Well, the first version has some low D notes on it. The Cult’s career wouldn’t have gone where it did if we hadn’t redone the album with Rick Rubin, but the originals have some interesting stuff.”

Did Rubin get involved in the studio?

I was tied down, basically. The question was, what was the least I could play to make the songs sound good?

“Rick was very hands-on with arranging songs and getting Billy to play tight, with no reverb or letting notes ring. I was tied down, basically. The question was, what was the least I could play to make the songs sound good? Well, playing D was the answer, ha ha!

“Looking back on it, the job of a bass player is not to be front and centre, it’s to play your part in the bigger sonic picture. If that means playing D for three minutes, that’s what you do. If that means flying around, then great. That didn’t really happen in the Cult, although there was a lot of walking bass, especially on Sonic Temple. There’s a big long run at the end of the song Edie (Ciao Baby), which they bumped up in the mix. That came out of nowhere; it wasn’t planned.”

You played guitar for the Electric tour in 1987, while Stephen ‘Haggis’ Harris played bass.

“For that tour, it was easier to find a bass player to play the Electric stuff than to recruit a second guitarist to fit alongside Billy. I knew how Billy played, so it made sense to ask Haggis, who was using the stage name Kid Chaos, to play bass. There was a period when the band used to smash up the gear at the end of each show. I never did it myself, and I know Billy never smashed up any of his Gretsch guitars, but Haggis smashed the crap out of my 1967 Jazz on stage in Australia. I was by the side of the stage, waiting for the mayhem to stop. He walked up to me, gave me the neck and said ‘Sorry about your bass, mate’. I was completely shellshocked.”

Leaving The Cult

What other gear did you play in the Cult?

“A couple of beautiful active Spectors, and a Gibson EB-0 that looked great but sounded crap, so it never got played. It’s now hanging on the wall in the Hard Rock Cafe in Berlin. I also enjoyed using Ampeg SVT heads and cabs; I used to travel with three heads and 8x10s! That was once we’d graduated to large stages.”

Did you evolve as a bassist through your time in the band?

“Yes, Billy was keen that I become a proper bass player, learn from other bass players and live as bass players do, so I started trawling through old Jimi Hendrix material to understand how to fill out the sound in a three-piece. I also listened to Cream playing live, which is incredible stuff. I tried to broaden and stretch myself in this way, although I didn’t get it completely right until I left.”

Why did you leave?

The albums we recorded seem to have been as influential to people as the Damned albums were for me, which is great to hear

“Mostly because I’d got married and it was time to have kids. You can’t be in a band and be a parent and do both jobs properly. Also, after seven years of being on the road, Ian and Billy had grown apart, with separate tour buses and so on; the atmosphere wasn’t great. But me leaving was reasonably amicable, now I look back.”

What happened next?

“I lived in London for a year, trying to make it as a producer, but people weren’t interested in me because fashions change so fast, and because the Cult were never in fashion anyway! So we moved to Toronto for four years, where the Cult had always gone down well, and I had a great time producing a few small bands. I left the music industry after that and went back to college to study graphic design, and now I work for a software company in Buckinghamshire.”

Are you still playing?

“They say you’re a bass player for life, and indeed you are. I did a couple of guest spots with the guys when they were doing 25th anniversary tours for the Love and Electric albums in 2009 and 2012. It felt completely normal, although it was harder work, now I’m 25 years older. It was great fun. No rehearsal - just a quick soundcheck to see if I could still play, ha ha!”

Where can people keep up with what you’re up to?

“I see fans from every era of the Cult’s career on my Facebook page. They have a huge following all over the world. The albums we recorded seem to have been as influential to people as the Damned albums were for me, which is great to hear.”

“I’m beyond excited to introduce the next evolution of the MT15”: PRS announces refresh of tube amp lineup with the all-new Archon Classic and a high-gain power-up for the Mark Tremonti lunchbox head

“These guitars travel around the world and they need to be road ready”: Jackson gives Misha Mansoor’s Juggernaut a new lick of paint, an ebony fingerboard and upgrades to stainless steel frets in signature model refresh

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)