The Comet Is Coming: "Real World has more gear than I’ve ever seen in my life - it's a studio geek’s dream"

As the electro-jazz trio record their third album at Real World studios, Danny Turner chats to synth magician Danalogue

Formed in 2013, London-based trio The Comet Is Coming remain hell-bent on defying electro-jazz orthodoxy.

Comprising saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings, drummer Max Hallett and synth player/producer Danalogue, since their 2016 debut album Channel The Spirits the threesome have synergised their collective talents to create an unrelenting smorgasbord of jazz, electronica, funk and psychedelic rock.

The last few years have been spent on tour or constrained by Covid, hence the band decided to get out of the city and record their third album Hyper-Dimensional Expansion Beam at Peter Gabriel’s Real World studios.

With the help of their engineer Kristian Craig Robinson, the group embarked on a four-day process of intergalactic improvisation before returning to Danalogue’s studio for a torturous round of post-production.

Tell us a little bit about your personal history and how you got into music production?

“I had a mate whose dad had loads of old Akai samplers, keyboards and mics and he showed me the ropes in terms of making demos on old DAWs like Cakewalk. The same friend was also in a guitar class and he rang me up one day and said, ‘You’ve got to get this keyboard’ – it was a Roland SH-09 and I immediately thought ‘this is me’ and still use it now.”

Before forming The Comet Is Coming, you were already working with Max Hallet?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Before we created Soccer96, Max and I were in a six-piece band making these epic 20-minute post-rock orchestral things, similar to bands like Godspeed. We were in Brighton at the time and everyone had a DIY attitude, so I bought a secondhand laptop and was convinced that I’d be able to mix the album myself. The mixes sounded a bit lo-fi, but over a period of time we eventually learned how to make our own sound.”

It might be worth pointing out that Soccer96 is a band you’re in and not a video game…

“It actually came from a Nintendo football game. Max sent me five cartridges with different names that were all quite weird and I ended up sending them to this text service called AQA, which would basically answer anything you sent them. They texted back within a second saying, ‘definitely call your band Soccer96’.”

The name The Comet Is Coming also has an interesting derivation…

“We’d already been recording at a live music space called the Total Refreshment Centre, which used to have its own vinyl library. We’d been talking about a name for the band but I wanted it to just reveal itself, so we were scooting through a load of vinyl one day and the title was there staring at me on the back of a Radiophonic Workshop LP. Shabaka and I just nodded to each other and I phoned Max and said, ‘Get down here, now’.”

Did the name help guide the direction of the music to some extent?

“It did help, yeah. The next recording we did was Star Exploding In Slow Motion from the Prophecy EP and it felt like we didn’t have to hide from making these really cosmic, grand statements. One of my favourite things to think about is how the likelihood of us all existing in the first place is so tiny. It’s quite mad that a cosmic pool game has led to the evolution of the most organically advanced species that we know of and when I step up to the instruments that’s something I derive a lot of inspiration from.”

Shabaka once explained that the band’s aim was to destroy musical ideals. Do you see that as part of jazz music’s intention?

“I don’t feel that I’m an authority on jazz and despite having a saxophone player in the band never really thought of us as a jazz group. It’s obvious for a band to not want to categorise themselves, but we’ve invariably been called everything from astral rock to cosmic jazz and space funk. I’ve always liked bands that are weird outliers and hard to define, but maybe what Shabaka is speaking to is the idea of improvisation. When we start playing we go on these long journeys, do a lot of listening and try to let the music guide us. In that sense, there are no ideas at the beginning, they just reveal themselves and we polish them up later.”

So what sparked the idea of recording Hyper-Dimensional Expansion Beam at Real World studios?

“The first two albums were conceived at the Total Refreshment Centre because we’d done our first few gigs there and it was just a hub for us, but in the middle of the pandemic we all felt trapped in London so we thought we’d just get out of town and go to the countryside. I’d already been to Real World with Sarathy Korwar and thought it was amazing – it has incredible gear, bedrooms and a guy who cooks you lunch and dinner every day. It just felt like a level up in terms of the equipment and the whole experience. I basically wanted to make a huge sound that was similar to how we played live and it felt like being in a big studio would help us to realise that goal.”

Did you bring your own gear into Real World to create a more familiar setup?

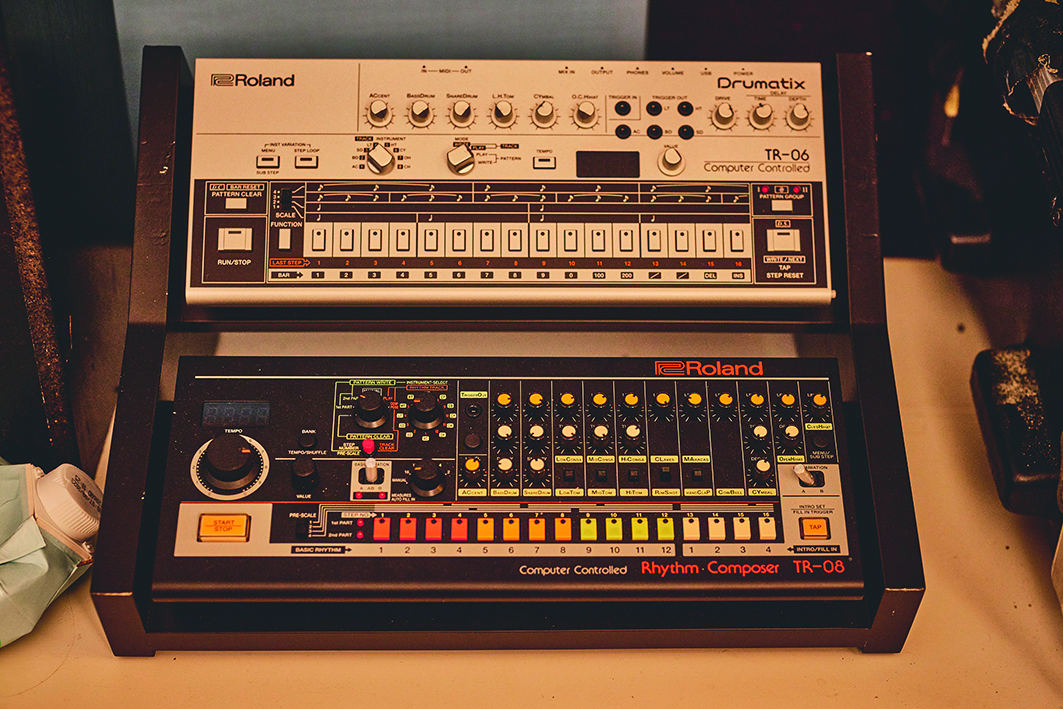

“Max took his own drum kit and I took both of my Juno-60s and the Roland TR-808. We traditionally use a drum machine as the click, but we connected the 808 to one of the Junos to create arpeggiated patterns and used the other one for chords. I also took my Roland SH-09, mainly for bass, and a Moog Sub Phatty because that’s quite cool. Real World has more gear than I’ve ever seen in my life, but it’s all gear from the old days. They had ten UA-1176 compressors in a row and seeing those all chained together was a studio geek’s dream.”

Did you tap into a lot of that vintage gear?

“They had a Studer 2-inch 24-track tape machine, which has always been my dream to record on because we always record to tape. Normally those big tape machines are just for show, but Real World got it serviced on the morning we arrived. They have hundreds of pieces of outboard but the assistants told us that nobody ever uses them, so we brought in our own engineer Kristian Craig Robinson and as the days wore on he was getting the assistants to plug in more and more gear until pretty much everything was on. They looked so chuffed and Kristian loved it.”

You spent four days there. Was the idea to create a series of demos through improvisation?

“It’s almost like we’re recording demos but the demos are the record. As long as it’s set up like a serious session and everything’s miked up, recorded to tape and you’re going through the mixing desk, when you hit record it can sound like a finished recording even when you’re playing something for the first time.

It’s almost like we’re recording demos but the demos are the record

“Some of the pieces of music we recorded went on for a good 40 minutes, so we were searching for what we wanted and over the course of a few days started to really lock into what we were looking for. We basically recorded nine hours of material over the four days we spent at Real World.”

Having played together for quite a while, have the three of you developed an almost telekinetic understanding?

“Weirdly, it always was pretty telekinetic. Neon Baby from our first EP was born out of playing a riff, Max coming in with the drums and Shabs immediately coming in with a riff of his own. I can vividly remember thinking about where I should put the chorus then switching down to another chord and giving Shabs the eye so he could change his riff.

“When that happens, you intuitively feel that you can go back to that section again. Sometimes it works out well and other times you can hear in the playback that only one of us is doing something good – then it becomes a jigsaw puzzle where you have to copy, chop and arrange a 20-minute piece of music and distil the whole thing into four minutes.”

Presumably, everything’s stemmed out to enable you to cut and paste those individual parts?

“It’s stemmed out and sometimes those stems have a kind of beautiful organic form and other times I’m acting more like an electronic producer and using the scissors a lot. Because it’s to tape and not really to a click, it’s all done by hand, so I’m often cutting these long drum machine waveforms. It’s really laborious and Max and I often look at each other and wonder why we’re doing this, but I believe in the process because it sounds like nothing else and gives us our own sound.”

At the same time, is there a risk of over-editing and losing the feel of the performance?

“We like to turn some of the tracks into singles and have a punchy sound with lots of movement and sections, whereas others we like to leave quite open. For example, Angel Of Darkness from the new record takes a super open and organic form, whereas the track Pyramids is much more organised and distilled to a tighter structure. But you’re right that it’s a real balance because you don’t want to over edit and create something sterile.

The opening stage is all about free expression – getting everything out without thinking twice

“The opening stage is all about free expression – getting everything out without thinking twice and trying to make this beautiful creation, then we normally put everything into a drawer for three months. When you pull it back out you can’t remember anything you did and it sounds like a different band, and then you go through the tortured artist part where you’re asking yourself how you want to frame all of these ideas. That part can get quite dark because the more you listen and try to polish and perfect something the more you start to go a bit crazy.”

Did only having four days of recording at Real World introduce an element of pressure?

“Funnily enough, this is actually the longest we’ve spent in a studio together – the other albums took about three days. We’ve always recorded that way and trust the fact that we’re going to play a lot of terrible stuff and some good stuff, knowing that once I bring the recordings back to the studio to arrange, edit and do the overdubs everything will be fixed in the mix.

As soon as we captured that I knew we’d be okay – it was like bottling lightning

“But, there is a radical urgency knowing that you have to make an album in a limited time frame. It feels intense – in fact, on the morning that we drove to Real World I almost couldn’t talk because there was so much going on in my head about whether we should create upbeat dance, psychedelic rock or jazz tracks. I remember that the first take on day two was brilliant and as soon as we captured that I knew we’d be okay – it was like bottling lightning.”

Looking back, how beneficial do you think working at Real World has been to the end product?

“When you listen back at Real World they have huge speakers that are like a PA system – it’s insane and makes everything sound absolutely massive. There’s something about that huge, maximalist, widescreen sound that’s a bit ’80s and we started climbing into that – it facilitated a slight grandioseness that we leant into.

“But I do want to big up Kristian one more time. He not only recorded all 24 channels to tape, but when we digitised that he ran it back through another 48 channels of delays, reverbs and flangers. Although we did a lot of effects in post, Kristian was pretty much co-producing and deciding different effects on the fly. Having that smorgasbord of effects to pick and choose from really helped when it came to the mix. ”

When overdubbing back at your own studio, did you have to work a bit harder to match the quality of what you’d recorded at Real World?

“I’ve got a desk here, good compressors and the synths are all classics so they normally slot in nice and easy, but I was more disciplined about the process this time. Whether we had a 30 or 60-minute jam, we’d edit the tracks down and resist the temptation to record additional parts. When we did overdub synths and percussion to add extra layers, we sent sounds out to the Space Echo or various compressors before mixing.”

Did that apply to Max’s drums too?

“One of the issues we had is that because we’re chopping together different parts of different tracks, sometimes the drums will just stop unceremoniously. To get around that we might take an end section of Max’s drums and run it through various echoes, reverbs and flangers to blur the edges a bit. On some tracks we’d add whole other bits of drum kit and there’s a lot of extra percussion that went down too.”

The use of saxophone is a massive part of your sound, so how are you treating it alongside all of the other instrumentation that you employ?

“The first time Shabs came into the TRC to do our debut EP, the first thing we did was to put his saxophone through a guitar amp. There’s no dry sax on that first record, it’s all going through a ratty old amp that was distorting like crazy, so if you listen to a track like Cosmic Dust on the first LP the sax almost sounds like Jimi Hendrix. I remember looking at Shabs and his eyes would light up because it was so different to what he was doing with his early Sons of Kemet stuff.

The first thing we did was to put his saxophone through a guitar amp. The sax almost sounds like Jimi Hendrix

“It gave him something to really fight against, but as time has gone on and we’ve gained more knowledge of mixing records, we’ve been gradually cleaning up that sound and given ourselves a bit more control. At Real World, we had a dry mic and a line running into another room with Shabs’ sax going like the clappers through a vintage sound amp and a real plate reverb.

“When we got back here, we saturated the sax by putting it through the Space Echo and an 1176 compressor and ran it through the desk with it sounding really hot on the gain and then put it through an Estradin Effekt-1 Russian flanger. I don’t know why, but I’m giving away all of my secrets here [laughs].”

When did you discover your Brick Lane studio?

“It must have been about four years ago. DJ Simbad had been here since the late ’90s and was about to move to South Africa when he handed the baton to me. It was a massive honour and I didn’t think twice because the studio’s had the likes of Roots Manuva and Flying Lotus in here so the walls have an epic vibe.

“This whole building used to have lots of studios and was all music management and distribution, raves and parties, but the whole area has been gentrified and this room is the last one left since those early days. Above the cloth roof panels is literally a bunch of cardboard boxes for sound proofing and there’s no window in here at all so it can’t be gentrified.”

You frequently record to tape, so what are you using to achieve that?

“I’ve got an Otari MX-70, which is a 16-channel tape recorder with a CB-117 remote control unit that stretches across the room so I can operate the tape machine from the desk. It was made in the ’80s and looks like something from Star Wars when you turn it on.

It was made in the ’80s and looks like something from Star Wars when you turn it on

“Once I got my own studio it was always my dream to have a fully operational 16-track machine and it’s been serviced so it’s working really nicely. A couple of Soccer96 albums, Dopamine and Inner Worlds, were recorded onto this machine and I love recording to tape because it only lasts for half an hour, which helps you make time-conscious decisions.

“In fact, some of the best Comet stuff was recorded when there was only five minutes left on the tape because we’ve had to get all of our ideas into those five minutes. I’ve got it set up with the Apollo X16 interface, so I can record into the computer and run everything out onto the Otari or use the patchbay to have things come into the desk and record live straight to tape.”

You also have a vintage Revox tape machine?

“We used the Revox to master a Danalogue and Alabaster dePlume record. This actual machine is featured in a Peter Strickland film called Flux Gourmet. It’s a thriller that has something to do with food and music equipment, and they really needed one of these tape machines so I hooked them up with it.”

Is everything running through your Trident desk?

“It’s a flexi-mix Trident desk that’s very cleverly designed. It’s modular so you can set it up however you want, but I’ve got it set up with the maximum amount of channels that you can have. It’s got really extreme EQs, gritty gain pots and a really unique sound to it. It funnels the sound down an alley that’s not clean or modern-sounding, which is obvious considering it’s from the ’70s, but I love how it colours everything. The way it’s set up, instruments come into the desk and the direct outputs funnel into the Apollo x16 and then via the computer.”

Does the Jen Piano 73 keyboard get much use?

“It’s got a couple of broken keys, which is a bit sad, but it’s really cool because it has an in-built phaser, which you can change the speed of, and a vibrato setting alongside its basic piano sounds. We use it on a track called The Hammer. I normally have a Juno synth here but it got lost on the way to a show – so between playing in Porto and the Green Man festival in Wales, I had to run back here and drive the spare Juno down in the van.

It’s amazing to run drums through because the vocoder naturally picks up on your sibilance, which really brings out the hi-hats and snares

“I’ve also got a Jupiter-4 here and the VP-330 vocoder, which is great for when you want to sing through a synth. On the Soccer96 album Dopamine we wanted to capture the sound of artificial intelligence, where you’re not sure if it’s a robot singing or a human being. It’s amazing to run drums through because the vocoder naturally picks up on your sibilance, which really brings out the hi-hats and snares.”

What other vintage gear is integral to the The Comet Is Coming sound?

“Definitely the Space Echo, which we literally use all of the time. At Real World, we were running the bass synth into an amplifier in a separate room but it still sounded a bit dry and the Space Echo adds an unpredictable colour and warmth. You can drive it, so you get some tape saturation and because it’s an echo it can slap out sounds that are bit too in your face. I run everything in parallel, so you can have your dry and your echo panning around to give it that extra dimension.

“It’s just one of those pieces of gear that you can do almost anything with and know that whatever you put through it is going to sound great. Another secret weapon is the Simmons Clap Trap, which is great for handclaps and percussive crashes – it’s on so many Comet tunes and all of the Soccer96 stuff. And not to be outdone, I’ve got Max’s donkey jaw from Peru. When you hit it, you can hear the sound of its teeth rattling and if you put it through the Space Echo it sounds incredible!”

Are you using a lot of in-the-box tools for mixing?

“I do need to use a lot of effects plugins for mixing. For an improvised jazz record it’s surprising how much of it needs to be organised, so although I use a lot of outboard compressors I’m also using plugins like Decapitator on the drum bus and the UAD 1176 Rev A. For mixing, I’m using a lot of precise parametric EQs like the FabFilter Pro-Q3 for cutting and removing, and I find that Abbey Road Chambers is really good for adding a vibe to kicks and snares.”

You’re not one for using synth libraries?

“When it comes to using analogue gear I feel like I’ve boxed myself into a corner, but I quite like those boxes. I’ll always use outboard synths, but when it comes to editing I’ve embraced the digital world because cutting tape is an absolute nightmare.”

Danalogue's top kit

- Roland SH-09: “My absolute favourite synth. It has gritty filth and a merciless brutality.”

- Roland Juno-60: “Voltage in technicolour, every chord feels expressive and warm.”

- Roland VP-330: “A vocoder with a mystical edge, it’s the sound of awakening AI with onboard string and choir synths.”

- Jen Piano 73: “A shimmering chime and harpsichord-like attack with a rich inbuilt flanger.”

- Ensoniq ESQ-1: “A choir sound that I love – the notes sound different vowels, making a transcendent human/robot hybrid.”

- Simmons Clap Trap: “You can manipulate a sampled clap to different pitches/lengths and blend with white noise.”

- Roland Space Echo RE-201: “Put any sound through its tape vortex and find colour, depth, saturation and slapping echoes.”

- Eventide Harmoniser H3000: “I mainly reach for the flangers, stereo imaging and delays.”

- Great British Spring Reverb: “A two-channel spring with a long tail and plate-like shimmer.”

- Lexicon PCM60: “Just close your eyes, press the buttons

and bam!”