The beginner's guide to: dubstep

A heady mix of Jamaican-British sound system culture, garage and broken beat, dubstep was a defining ’00s sound

Of all genres with complex legacies, dubstep ranks as one of the strangest. It’s less than 20 years old, yet already feels like it’s been through more ups and downs than a low-frequency oscillator. A victim of its own success in many ways, the sound which felt so fresh in early 2000s London soon hit the global mainstream and imploded.

Its roots go deep into Jamaican-British sound system culture, incorporating the heavy bass elements of dub reggae, the skippy syncopated drums of jungle, drum & bass and broken beat, plus the deft melodic lightness of UK garage.

Dubstep emerged as a distinct form around 2001, when the dark garage of producers like El-B and Zed Bias morphed into something new, coalescing around 140bpm with a strong (but not mandatory) emphasis on halftime two-step rhythms, an obsession with sub bass and a minimal beat overlaid with more complex percussion.

The role of specific clubs and record shops is often overplayed in genre histories, but for dubstep it’s hard to overstate the importance of the Big Apple record shop in Croydon and the FWD>> (‘Forward’) night at the Velvet Rooms in central London (later moving to Plastic People, Shoreditch).

Of all genres with complex legacies, dubstep ranks as one of the strangest. It’s less than 20 years old, yet already feels like it’s been through more ups and downs than a low-frequency oscillator.

At the former, staff and regulars included DJs and producers Artwork, Hatcha, Mala and Coki of Digital Mystikz, Loefah, Skream and Benga. At the latter, the nascent scene would gather to test out new dubplates and luxuriate in sub bass, with regular DJs including Skream, Kode 9, Benga and Ramadanman (aka Pearson Sound). Digital Mystikz would also go on to launch their own DMZ night, with regulars including Youngsta and Pinch, among others. From this central core, a scene grew.

Dubstep quickly spread from its London roots, with strong scenes in cities such as Bristol and Leeds, then globally. By 2005, the sound was widespread. Aphex Twin’s Rephlex Records had released two (somewhat misleadingly titled) Grime compilations that included dubstep tracks, while Radio 1 DJ Mary Anne Hobbs’ show Dubstep Warz brought the sound to her large audience.

In retrospect, the variety of sounds that got called dubstep in the mid-to-late ’00s is oddly diverse: from the crystalline digital funk of Joker’s Purple City (2009) to the lolloping skank of Digital Mystikz’s Anti-War Dub (2006); the precise minimalism of Skream’s Midnight Request Line (2005); the disorientating melodic patterns of Benga & Coki’s Night (2006); and the retro-futurist chiptune swagger of Zomby’s One Foot Ahead Of The Other (2009).

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But the downfall of dubstep as the hype genre of the early 21st century was probably on the cards from 2009, when tracks like Rusko’s Cockney Thug marked a trend for ever-filthier bass sounds, big drops and more aggressive production.

By the early 2010s, producers were almost trying to outdo each other with dirty sounds. Eventually, tracks like Flux Pavilion’s Bass Cannon (2011), Excision’s X Rated (2012) and Skrillex’s Scary Monsters And Nice Sprites (2010) would be pejoratively termed ‘brostep’.

This newly evolved strain of dubstep represented big shifts not just sonically, but also in terms of a move to festival stages rather than sound systems and a trip across the Atlantic, as US producers took increasing interest in the sound, feeding into the growing EDM culture.

Since the early-to-mid 2010s, dubstep has been in limbo. Bigger names became stars and shifted to EDM territory; some retreated to old-school sounds. Others, like Skream, shifted styles almost entirely, exploring techno, disco and house in order to break free from dubstep’s constraints.

Dubstep’s legacy in 2020? It’s complicated, but maybe enough time has passed to look back and admit that it was one of the most exciting musical scenes of the last two decades.

Three software staples to nail the dubstep sound

NI Massive

First released in 2007, NI’s wavetable synth plugin arrived just in time for peak dubstep.

The combination of wavetables, interesting filter modes and powerful modulation made Massive an obvious choice for anyone looking to create the heavily LFO-modulated wobble bass (‘wubwubwub’) that characterised a healthy proportion of dubstep tracks.

If you didn’t want to create your own sounds, NI helpfully included plenty of presets that fit the bill nearly as well. The ‘Brutal Electro’ sound in particular will be familiar to anyone who’s listened to late-2000s dubstep.

Image-Line FL Studio

Formerly known as Fruity Loops, the step sequencer-based approach of FL Studio lent itself well to dubstep.

It’s hard to argue that any particular DAW is the ‘best’ for dubstep - there’s even a story that Benga got his start making tracks on his Sony PlayStation - but FL Studio was certainly the choice for a number of dubstep pioneers including Skream, Plastician and Benga himself, once he graduated from his games console.

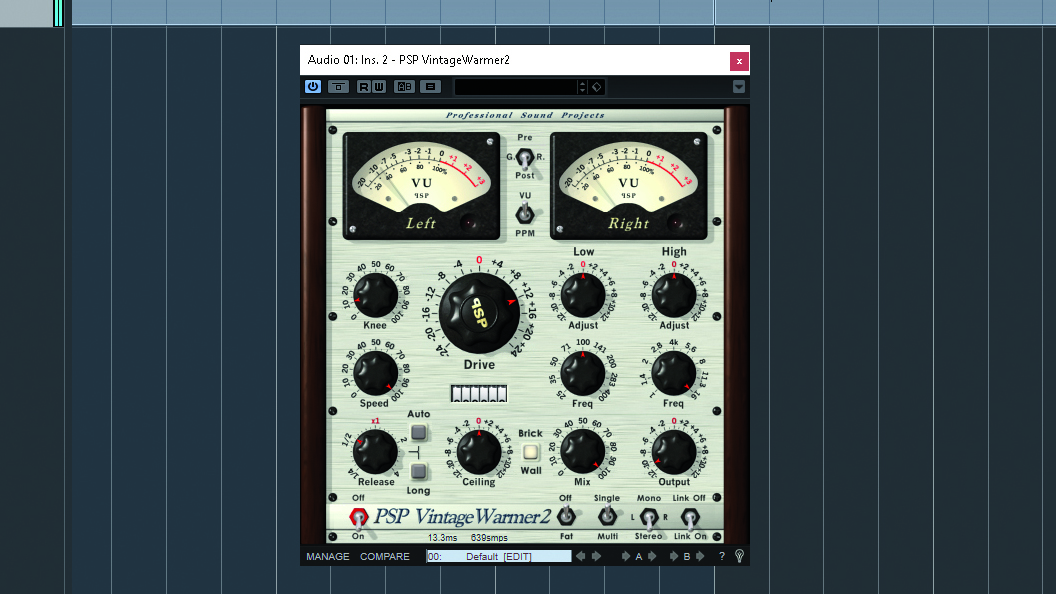

PSP VintageWarmer 2

Given its original roots in sound system culture and high-quality club systems, it’s easy to understand why dubstep always had an obsession with mixdowns, sound quality and production values.

It’s therefore pretty impossible to pinpoint one single piece of software that would have helped with the obsessive compression, forensic EQ bracketing and complex sample layering that defined so many classic mixdowns, but if we were to do that, an honourable mention would go to PSP’s VintageWarmer, which was a favourite of lots of producers for its quick and easy approach to saturation and loudness.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.