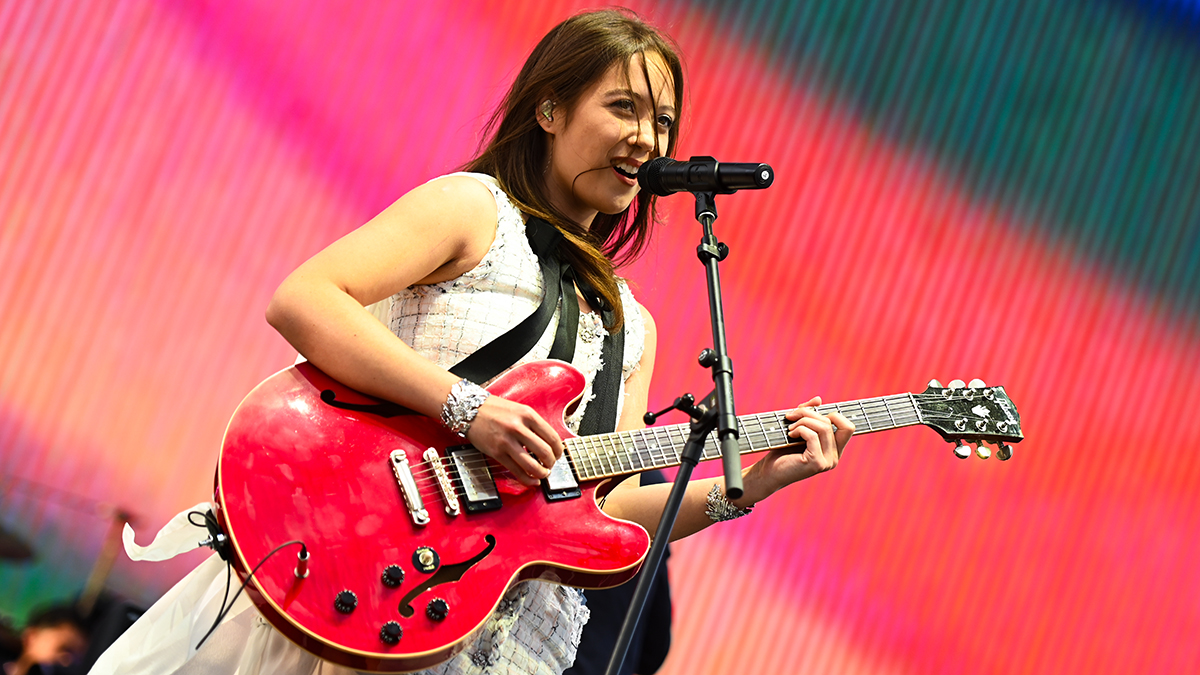

The Anchoress interview: “I needed to be physically in there, manipulating the sound with my hands…”

As multi-instrumentalist Catherine Anne Davies gets set to finally release her second album as The Anchoress, she talks to us about the sound of trauma, joy of being in control, plus working with James Dean Bradfield and Bernard Butler

The UK is between lockdowns as we talk to Catherine Anne Davies in the build-up to Christmas, but life is still as far from normal as it can be for a touring musician. Live music is on hold, and so has been the release of The Anchoress’s second album, The Art Of Losing, which was originally slated for a March 2020 release and will now come out in March 2021. The wait is something Davies says she has come to appreciate, and what has happened to the world in the meantime has certainly sharpened the blade of an album dealing with grief in its many forms.

“The album was actually finished in 2019,” Catherine explains, “so I got to sit with it for a lot longer than planned, but that’s had its upsides in terms of my having more time to process a lot of the things I’m talking about on the record.”

Complete control

"I am still very interested in the album, as a collection of songs, articulating something"

Like her debut, Confessions Of A Romance Novelist, The Art Of Losing brings together a range of styles, instruments and musical outlooks to nevertheless create a coherent whole with a clear artistic vision.

“I think that's what's so wonderful about having complete control,” Catherine expounds, “as pretentious as it may sound, it's my vision alone. You don’t have to compromise what you're trying to do, you know, so you’re just articulating something really pure. And it is a sum of all of my influences and interests, but I really strived very hard to make the album a coherent body of work. I am still very interested in the album, as a collection of songs, articulating something. It’s what interests me, I’m terribly old fashioned.”

That level of control is reflected not only in Catherine producing the record herself, and we’ll hear more about that process later, but as a talented multi-instrumentalist playing almost everything you hear.

“I even played some drums on this record,” she tells us, “albeit piecemeal, tracking the cymbals separately, then doing some toms separately, percussion, so not playing the full kit. But I embraced the way the record turned into some one-woman insane vision, for various reasons.

“I do have collaborators on the album, though, including Sterling Campbell, David Bowie’s drummer, who contributed remotely from New York, and James Dean Bradfield of Manic Street Preachers, who I was very lucky to have playing guitar on one track [Show Your Face] and also singing a duet [The Exchange]. So where I needed to bring others in I was able to, but partly through needs-must I became a jack of all trades on this.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I also bought some more vintage synths, quite a few more guitars, some mic preamps found their way into my checkout basket… but that was me building my studio, and thank goodness I did that.”

Preacher man

"“Manic Street Preachers were my obsession growing up”

Getting James Dean Bradfield on the record was personally important to Davies (“Manic Street Preachers were my obsession growing up”) having duetted with him on the Manics’ 2018 album Resistance Is Futile, so did she give the guitarist license to go his own way with his contributions?

“I’m the fucking producer, mate,” she laughs, “what I say goes… so I gave him quite a lot of direction about what I had in mind [on Show Your Face], something angular.

We talked a bit about Magazine, and he’ll slap me on the wrist for this but also about The Holy Bible and the guitar sound that he had on that record in particular. I wanted something aggressive and angular and arresting, but I also wanted him to have fun.

“Obviously he’s an incredible player, I didn’t have to tell him what notes to play, although I think I did make the mistake of trying to talk to him about the key of the piece. I didn’t realise that James doesn’t really think of music in that way. Who knew that such an incredibly technical player could do it all by ear and feel? That meant our conversations became about mood and sonic references, rather than ‘Could you play a descending chromatic scale in the key of F#?’

“The smile I had on my face when that guitar file came in…”

Nightmares on wax

"One of the big sonic features of the record that I exploited a lot is the use of analogue gear to manipulate and reconstitute sounds"

Davies might have made the most of the digital technology available in securing her collaborators, but The Art Of Losing is, at its heart, an analogue recording.

“One of the big sonic features of the record that I exploited a lot is the use of analogue gear to manipulate and reconstitute sounds,” she explains, “so there are a lot of instances where I was running things back through the Watkins Copycat, physically manipulating the tape. I used the Leslie cabinet a lot too, so I was relying on a lot of old, traditional studio techniques to get the kind of dreamscapes I was interested in.”

“It was very difficult for me to consciously think of a way, not to record the sound of trauma, but to incorporate that into the songs and the production of the record"

Talk of sonic dreamscapes leads our discussion in the direction of an essay Davies once wrote for the NME about the films of David Lynch and their true influence on music; in it she talked about Lynch’s ability to bleed dreams into reality, and it is something Davies does musically throughout The Art Of Losing. The track Paris is a particular standout.

“There are all kinds of ways of borrowing from film and cinematic structures, but also techniques, you know, sonic collages and things like that,” she explains. “Part dreamscape, I think is how I described Paris, part dreamscape and part commentary. I'm interested in other people's voices, and bringing those together to comment upon my own internal monologue in some way.

“It was very difficult for me to consciously think of a way, not to record the sound of trauma, but to incorporate that into the songs and the production of the record. Because that is what I was experiencing in my life at the time and was hanging over me, ever present, there was no way I could have escaped that [Davies has written publicly about miscarriage and childloss]. I think I would have had to have taken a long time out if that wasn't going to creep through.

“I guess a lot of what you hear as the more disturbing aspects of The Art Of Losing are about how we articulate trauma through music, and it can have a nightmarish quality, a dreamscape quality and also a fracturedness, I think. We ourselves fracture when we go through difficult and extreme experiences, and I wanted to reflect that in the multiple voices on the record, the way we are broken into pieces at moments of extreme stress and extreme loss.”

Getting physical

"I’m a real fan of not being precious about the original signal"

But going back to the process of capturing those emotions on record, Davies has much to say about the use of analogue equipment that we touched upon earlier. Even music that was originally recorded digitally, went through an analogue reshaping.

“Because of the way a lot of the music was recorded, on the road, there was a lot of reamping going on. All the bass was just DI’d in, in the first instance, and then reamped through a Selmer cabinet with a D12 and a D9, and I think a Chandler Red 47 as well, and then I’d throw that through the Leslie as well. I’m a real fan of not being precious about the original signal, I’m more interested in the manipulation of the signal later on. I think you’re less likely to see that in modern production techniques.

“I think maybe the subject matter I was dealing with meant that I felt I needed to be physically in there, manipulating the sound with my hands, or pushing it through the air in a different way, like with the Leslie cabinet. That cabinet is manic when you really look at it, that manic rotation of the horns inside the box, which is a little bit like the way your head feels when it’s spinning through grief. The same with the Copycat loops, I’m sure there are a lot of reasons, if I analyse them, why I chose the techniques I did.

"What do you do when you’re sad and lonely on the road? You sit on eBay and buy gear"

“But then why are there so many vintage synths on the record? Partly because what do you do when you’re sad and lonely on the road? You sit on eBay and buy gear, and then you write on that gear. So that’s how the sound of the record evolved, through my gear acquisition habit. There’s a lot of Prophet-6, and Oberheim OB6 as well, a lot of Jen SX 1000 on there, and so I guess it has an authentic sound of that era. I didn’t want to use digital modelling, I needed to feel the weight of the history under my hands, a luxury I could afford due to touring a lot with Simple Minds. I realise how privileged I am to be able to have access to that gear, and it became really important to me to be certain of the sound I wanted to capture.”

As someone who produces her own work, Davies sees the whole musical process, from writing through recording to production and post-production, as one.

“There were times I was writing straight into ProTools, so the song didn’t exist before I was producing it,” she explains. “That’s the beauty of working alone, you don’t have to create a demo to translate it to someone else. That’s what the Anchoress name is about as well, being cut off and alone in a room, communing with your thoughts… I think this second album is where the name has come to mean what it was intended to in the first place.”

New Feelings

"By its very nature The Memory Of My Feelings is such a different record from an Anchoress record"

Last year saw the release of Catherine’s collaboration with former Suede guitarist Bernard Butler…

“Obviously he's a phenomenal guitar player and he has a very identifiable style. You know, I think he and James are the two big talents of their generation who have that thing that when they play, they sound exactly like them. But for me, I would say I’m actually a big admirer of his production and his arrangement. His enormous talent as a producer is somewhat unsung, he’s incredibly skilled.

“By its very nature The Memory Of My Feelings is such a different record from an Anchoress record, because when you come in together and it’s two people that have got different skill sets, even if they massively overlap, you've got to make space for each other. So that necessitated me kind of giving up a lot of control that I would normally have to have.

“But the interesting thing about the timeline is that we actually made that record before Confessions Of A Romance Novelist came out, and we wrote the last batch of those songs in 2015. So I would say that there were certainly things that I learned from Bernard that have been percolating in my mind for that long, but in my timeline of creation that and The Art Of Losing are so far apart, it’s been five years.

“But we’re both really happy that it did finally find a home at Needle Mythology and got released. We're both really proud of the songs that we wrote, and happy that finally other people got to hear them, because it was just me and him for a long time, texting each other occasionally to say it’s such a shame that never came out because those songs are quite good, aren’t they?"

The Art Of Losing is released on 12 March via Kscope. For preorders visit theanchoress.tmstor.es

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track