Since 1992, Tori Amos has released 10 albums of adventurous, darkly compelling pop, including that year's multi-platinum Little Earthquakes and 2006's million-selling Boys For Pele. In 2009, however, the singer felt the need to walk away from contemporary songwriting, and she embarked on a series of stylistic departures. She tackled classical music (Night Of Hunters), reworked her catalogue with an orchestra (Gold Dust) and meditated on the seasons (Midwinter Graces).

"Sometimes you just need to do something different," Amos explains, "and in my case, I had to explore a number of different directions. Those experiences gave me such a great amount of energy. I was involved in all of these levels of collaboration and creativity - it was exciting and rejuvenating - so I think there was a freshness that I brought back to these songs."

The songs that Amos speaks of can be found on her bold new album, Unrepentant Geraldines, a stirring, hypnotic collection of deeply personal, idiosyncratic pop largely inspired by visual artists, specifically '60s photographer Diane Arbus and 19th century Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne. Amos sat down with MusicRadar recently to talk about the new album, her favorite piano and how she keeps her voice in top form.

After taking a break from pop music, did you find that you came back to the genre differently on this album?

"Well, making this album was certainly different - I can tell you that. We were forced to make this album differently because I was in the middle of those other projects. In the past, we would gather the musicians and bring them in to track in the traditional way, but things were a little different this time. I was in the middle of The Light Princess and had finished with Deutsche Grammophon. Various songs would come and visit me during these last few years, but I wasn't under any pop obligations at the time. So I kept the songs secret - I didn't put them down, didn't play them for anybody.

"Once it became sort of time to do something, I played these songs for [engineer and husband] Mark [Hawley], and he said, 'You've got to put these down.' So I would jump on a train, and that's how it happened. Mark, [engineer] Marcel [van Limbeek] and I made this record. We worked everything out in the midrange first - keyboards and guitars - so we knew what we were dealing with. Everything else was then around that."

I don't get the feeling that you do, but do you ever think commercially when you write - "Hmm, will this be a hit"? Or are you only trying to please yourself?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I don't know if it's either. For this particular record, the songs were coming before I knew what I was going to do with them. I'd be foolish to not think that this was a possibility - making a record - so it's not as if it was a huge surprise, but when they were coming, their only purpose was just to deal with my life and work through what I was feeling. It wasn't to collect songs for an album because I was contracted. That sounds very corporate. [Laughs]

"See, when you're on an every-year deadline, which I had been, you're writing pretty fast. So this record was a few years of having these songs come to me, going through different experiences and having the songs reflect what I was going through. Sometimes I couldn't figure out what was going on till a song came to me."

The song America was inspired by Diane Arbus. How so?

"She was a jumping-off point. I was immersed in her work and how she saw things. That led me to other artists and photographers, like Dorothea Lange and people documenting America. Edward Curtis - he documented Native Americans. It was more than a hundred-year span, these photographs."

What's the meaning of the song America?

"The Native Americans that I've spent time with - and I'll see them again when I'm on the road - they think about future generations; they talk a community about seven generations from now. That's a lot different from those of us who are merely in the now. This led me to the idea of listening to people talk about there not being enough time in the day to be a good parent, to be good at work and to be politically aware all at the same time. I think they want to be able to think about future generations, but they're just not at the point where they can get beyond the now. I was motivated to talk about the alter ego of an America that was looking at the issues and the consequences of issues as they come up."

There's some beautiful guitar playing on the album.

"Well, that's Mac Aladdin, who is Mark. He's been playing guitar on the records for years."

Do you ever write on guitar, or does Mark interpret everything you do?

"No. No, I never do. That's him. I'll be playing something on the piano and he'll play the guitar, and we'll work stuff out in that way. This album, again, was worked out on piano and guitar. It was that midrange, which is different from the way most albums get worked out."

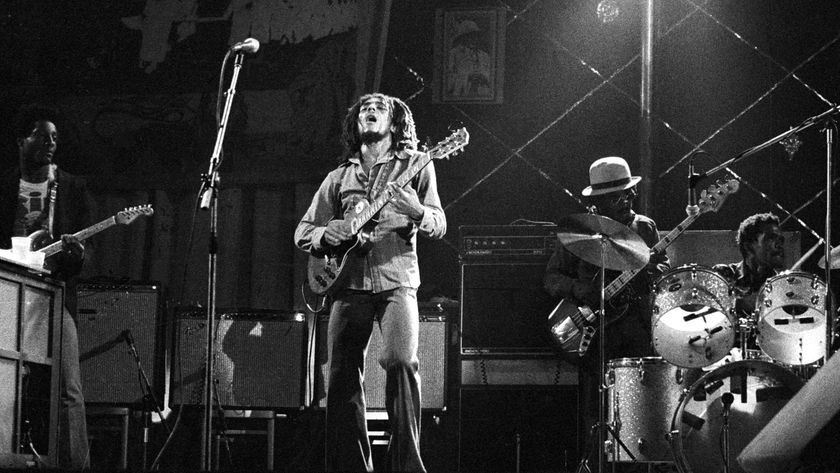

Amos on stage in Cape Town, South Africa, November 2011. © Jordi Matas / Demotix/Demotix/Corbis

It's interesting to hear you talk about the midrange. I never hear artists mention that as a signpost when cutting an album.

"That's where the melodies are happening. That's where the guitars and piano sit, in that range. Therefore, for the guitar to know what it's doing, and for the piano to know what it's doing, you can't take up that space with something else. Because we filled the conversation with keys and guitars first, we didn't want anything else to invade that space."

You have some ukulele on the record - on the song Giant's Rolling Pin.

"Oh, you know, there's just lots of instruments hanging around in the studio. Mark and I will run around and pick things up."

Is your choice of piano in the studio still the same, the Bosendorfer?

"Yeah, she's there. She's a wonderful creature - being. She gets very well looked after."

I remember [producer] Davitt Sigerson telling me how you guys looked at 10 different pianos when you were getting ready to make Little Earthquakes.

"Yes. [Laughs] Yes, I recall that very well. This piano has been in the studio now for a few years. I've been using her pretty exclusively."

I like how you call the piano "her."

"Yeah, they're all shes."

Musicians have off-days with their instruments - the guitar won't stay in tune, it's not intonated properly and so on. What happens when your voice won't do what you want it to in the studio?

"It can be frustrating, as you can imagine, especially when the clock's ticking. You have to pace yourself when it comes to your voice. It's a tricky instrument. That's the best thing about Mark having the studio in the old barn: If the voice isn't working, he can get on with other parts of a track while I nurse the throat and get it back to where it needs to be. If it takes a couple days, then it takes a couple days."

I've heard of so many tricks that singers have - cough drops, lemon wedges, tea. Do you have any secrets of your own?

"Cinnamon gum. I hide it to keep my mouth lubricated. When I'm recording, the guys can hear it - the mics pick it up - so I have to take it out when we're in the studio. Live, I have it. That's what works best for me. You're able to keep moisture in your mouth so the vocal cords don't dry out."

Your daughter Natasha sings on the song Promise. That must have been pretty thrilling for you.

"It was. We had a great time, we really did. She's into soul music, so I had to make sure that the song was right for what she does."

Does she want to follow in your footsteps?

"I don't know. She's 13, so we'll see. It's step by step, right? She's in school, and Mom says she has to go to school. [Laughs] She's been on the road since she was a year old. She knows it's tough out there; she knows the music business is about discipline. She's investigating different ways to tell stories through music but also through film and writing. So we'll see. She's exploring."

Do you share your cinnamon gum with her?

"Of course. I wouldn't hide it from her." [Laughs]

Tori Amos' Unrepentant Geraldines can be purchased at iTunes and Amazon. Deluxe Edition also available at Amazon.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues