Starting from scratch: 15 stops on the turntablism timeline

The rise of the performative DJ

Introduction

World famous Beat Junkie and Dilated Person, DJ Babu, was the first one to go by the title of a turntablist way back in 1995. He felt he was of a new breed of DJ, and needed to differentiate himself from the other jocks who merely played records.

Babu and his ilk are what scratch historian Mark Katz calls “Performative DJs” - those who differ from simple selectors by manipulating their records in real time.

From the early pioneer days of hip hop music, where the DJ’s name was the biggest one on the flyers, through the global battles for supremacy at competitions like the DMC, the art of playing the turntables like a musical instrument has developed into a highly technical sport over the years.

Innovations have occurred through a combination of happy accidents, intense study, ingenious ideas, and the rise of more and more sophisticated DJing equipment.

Let’s take a look back at some of the defining moments, key players, and the biggest game changers in the highly advanced DJ style known as turntablism…

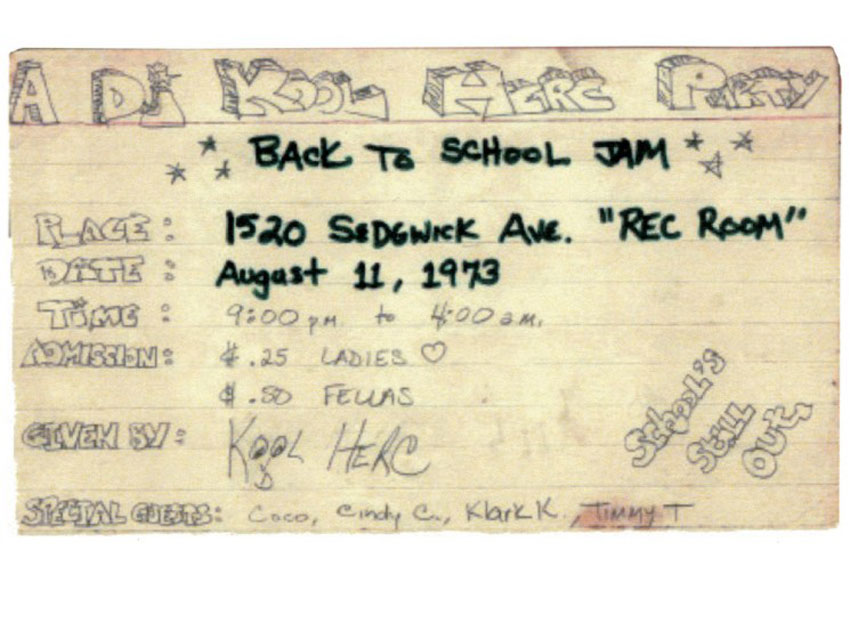

DJ Kool Herc's first party

On 11 August, 1973, the ticket price for the first ever hip hop gig would have set you back the princely sum of 50 cents (25 for all the ladies). In was then, at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx, between the hours of 9pm and 4am, that DJ Kool Herc played his very first gig, and where turntablism took its very first shaky steps.

Adopting the two decks and a mixer set-up style from the downtown Disco scene, Herc played his first party. The location was the common room in the tower block his family lived in, and the occasion was a ‘back to school jam’ fundraiser for his little sister. Rather than the Disco of the day, Herc dug deeper into the hard Soul of James Brown and the funkier side of Rock of bands like Babe Ruth, which would go on to be the backbone taste of early B-Boy get-togethers.

It’s at parties like these that he began to hone his famous ‘Merry-Go-Round’ technique - snatching and doubling the hypest sections of these beats for maximum carnage by using two copies of the same record.

Every genre has its creation myth - this is the Genesis of turntablism: The hip hop way of DJing.

Check out “The first hero of the hip hop groove” here as he takes his speakers for a spin around the Bronx…

Grandmaster Flash

The origins of turntablism proper can be traced back to legends like Grandmaster Flash. When the DJs of mid-seventies were mostly content to simply play one record into another, Flash helped develop and define many of the techniques modern scratch DJs now take for granted.

Listen to the epic The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel (just over seven minutes of madness - all live and laid down after a handful of takes). He’s cutting up two copies of a beat, scratching in melodies, layering up spoken word passages and changing up the selection within the blink of an eye.

For months at a time he would lock himself in his home laboratory dreaming up new theories about the science of mixing. Other pioneers like Kool Herc may have isolated the ‘get down’ parts of instrumental Funk records and doubled them haphazardly with two copies to extend the break, but Flash’s lightning fast techniques made that simple trick seem positively antiquated in comparison.

Peep Flash getting busy in the kitchen in this classic clip from the seminal Wild Style…

GrandWizzard Theodore invents scratching

Theodore Livingston was brought up in a hip hop household: His older brothers were party rockers who rolled with Grandmaster Flash. The tweenage Theodore tagged along, standing on record crates showing off his uncanny ability to needle-drop - his trick of looping a break by returning the stylus seamlessly to the start of the bar.

One day in 1975, whilst having a cheeky mix at home, his Mom interrupts. As the oft-repeated legend goes, and one he’s fond of retelling, young Theo doesn’t want to lose the beat he’s cueing in his cans so holds it rhythmically under his hand - a technique the old schoolers’ called rubbing.

As his Ma bleats on, he’s distracted by the rhythmical back and forth in the headphones. Something clicks, and after he’s appeased his old dear, he goes back to the sound and feverishly experiments with its musical potential.

Other DJs like Flash had heard the ziggy-ziggy before, but the prodigious GrandWizzard Theodore is widely credited with making this scratching sound part of his act. Thanks, Mom!

Hear the story from the horse’s mouth here…

The Technics SL-1200MK2 turntable

No turntable, no turntablism, right? And this is the model that the whole shebang was built around. Crucially these direct-drive decks had a solid-as-a-rock build and a sturdy tone arm that meant they came battle-ready straight out the box.

The ability to adjust weighting, needle placement, rotation speed and pitch control were all features intended to tickle the high-end Jazz and Classical audiophile who wanted to eek the finest sounds from his prized vinyl collection, but it was the DJ that unleashed its real potential.

Before decks like this model, disc jocks would gingerly manipulate the wax on rotation, now they could really get busy with it - spinbacks, scratching, needle-dropping and beat juggles would all eventually be realised on a pair of these. They might not have been built for the job, but they certainly became the company’s best employee (some say outselling guitars at one point).

Much like the skateboard or paint can, no one could have ever predicted just how far removed the humble turntable could have become from its intended purpose.

Since its arrival in 1979 the SL-1200MK2 quickly became the backbone of hip hop, and when the London Science Museum lit up a pair for it’s ‘Making the Modern World Gallery’, it showed that they went on to become much bigger than that.

Check this this run down of upgrading and customising the SL-1200MK2...

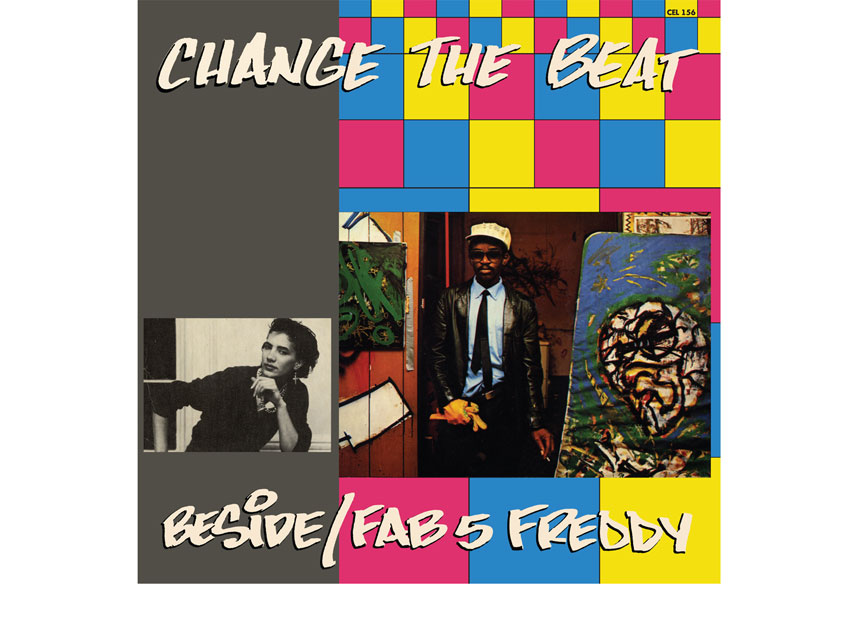

The '"fresh" sample

Cutting up the instantly recognisable “fresh” vocal sample is a rite of passage for any aspiring turntablist. It’s been drilled, twiddled, crabbed and transformed well past its expiry date, but they keep going back to it.

Is it the tail on the end of the phrase that gives it its playability, or is it the sonic texture of these brief vocoded lines that lends itself so well to a crossfader mangling? Either way, it’s been a port of call for a cut ever since it appeared on the outro of hip hop renaissance man Fab Five Freddy’s 1982 single, Change The Beat.

The original track (The Male Version) in its entirety is of little worth to samplers and DJs. But the flip (The Female Version) is the one with the covetable dialogue.

Online diggers’ Bible, WhoSampled.com, notes that one person has used the original, but over a thousand have nabbed the B-side. And that’s without counting every single scratch record it’s appeared on. F-F-F-Fresh!

Hear that famous sample come in at the 3.41 mark…

Grandmixer D.ST scratching on Herbie Hancock's Rockit

As the cream of turntablist documentaries (Battle Sounds, Scratch) rightly point out, Rockit was a seminal moment in the evolution of turntablism. Nearly every DJ of note has it down as their number one reason for picking up (or putting down) the needles.

The 1983 record and accompanying animatronic video were hits, but the Grammy performance blew minds. It was the first time many people outside hip hop had seen DJing, and for those that were already down, it was on some very next level tip.

Bandleader, Herbie Hancock, may have been centre stage with his keytar, and flanked by body-popping mannequins, but it was the glimpses of the figure of his DJ, D.ST, that turned the most heads. It was like he’d been beamed from space, a million miles from the Delancey St. in New York where he took his name.

Live and on record it was his percussive cutting and orchestrated scratching that gave the Electro instrumental workout it’s futuristic and shocking edge, and it showed the world that the turntables were now as relevant as any musical instrument.

Check out this D.ST-dominated live version of the song here…

The DMC World DJ Championships

Since 1985 the Disco Mix Club’s annual competition has been battleground for the world’s greatest DJs. To study the tapes of these events is to study the evolution of turntablism. The winners’ list reads like a who’s who, with greats like DJ Cash Money, the Dreamteam (Qbert & Mixmaster Mike), Craze (winning three times in a row!), C2C, and DJ Noize all taking the art to the next level in those six short allotted minutes.

The DMC organisation, not short of a few money-spinning ideas, began recording these legendary performances early on and packaging them to devoted students of the scratch. Each year the winner left with the glory (and electrical goods of varying worth), but left behind a record of their boundary pushing skills.

The next generation could now pause, rewind and study their idols’ deadliest routines and table turning techniques from the privacy of their own home. It turned many a bedroom DJ into actual winners in just a handful of years.

You can criticise the camerawork for missing the action when it began, the creakingly unhip Tony Prince for clinging onto hosting duties for so long, or some of the completely ill-advised special guests (Pete Waterman: “I hope your needles get stuck up your arseholes!”), but the DMC World DJ Championships has crowned the best who ever did it, and showed the rest just how to do it.

Watch a fresh-faced A-Trak killing it, 20 years ago, at the DMC world championships…

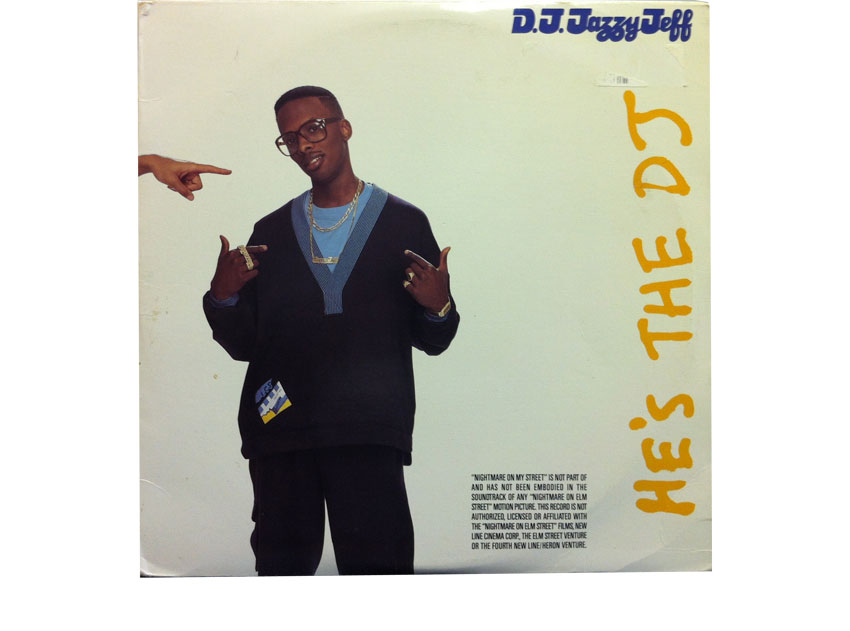

The transformer scratch

The origin stories of the transformer scratch centre around a triumvirate of Philly DJs: Spinbad, Cash Money and Jazzy Jeff. The first has been acknowledged as its inventor, albeit it in a rudimentary form, whilst the other pair are credited with developing it much further. It takes its name because of the sonic similarities it shares to the sound the characters from the Transformers cartoon made when they changed shape.

Jeff was the first to put it on wax with The Magnificent Jazzy Jeff. You might have clocked him at Union Square in ’86, but that recording wouldn’t be released for a couple more years.

Cash Money used the trick to dominate DJ battles around the same time, winning the New Music Seminar’s World Supremacy battle in 1987, and then the DMCs in 1988.

No one up to that point had managed to coax so much out of so little for so long as the masters of the transformer. To the first wave that caught it, it was like they possessed the power to turn back time. No wonder the New Music Seminar’s comp was called the Superman Battle…

Catch DJs Revolution and Jazzy Jeff transforming here…

Hamster style

Any modern scratch mixer worth its salt comes fitted with a hamster switch - That’s the little button that reverses the crossfader’s functionality. So, after you’ve enabled it, sliding the crossfader to the right plays the left deck, and vise versa.

Its purpose is not only to baffle House DJs, but also to open up a whole extra set of scratch textures for modern turntablists.

When the fader is working the wrong way round, the thumb and finger configuration of the scratcher is reversed. Fingers are more dexterous, and can now perform different variations on complex cuts like flares, as the crossfader is starting in an ‘open’ position. This helps to cut in and out of any sound you’re manipulating in the middle, rather than the end of the phrase, giving it a new spin to play with.

DJ Quest (Bullet Proof Scratch Hamsters) is credited with first stumbling on this approach in 1986 after wiring his decks up the wrong way and kinda digging it.

Through his battling in reverse, other DJs took note and tried to mod their mixers with homemade hamster switches. It was a boon for DJs used to rocking the channel faders, or line in/out toggles, at it suited their moves.

Vestax and Rane, sensing a demand, would make the switch an increasingly prominent feature on its next generation of scratch mixers.

Watch Studio Scratches’ DJ Short-e break down the hamster style a little…

DJ Cash Money at the 1988 DMCs

DJ Cash Money’s winning routine at the 1988 DMC mixing championships made a worldwide DJ community pick up their collective jaws and realise they had some serious catching up to do.

He stepped on the stage a star that night at the Royal Albert Hall. Hailing from the home of hip hop, he made everyone else immediately feel like pretenders. Then he opens with his own track, with his own name booming out of it. The very same track several other star stuck competitors had asked him to sign for them earlier.

It wasn’t all front though. His pioneering transformer scratches drove the crowd wild, rendering some portions of his set inaudible at times over the mass of horns and whistles.

He span round pulling B-Boy poses, showcased some of the funkiest doubles this side of a DJ Steve Dee routine, and switched the crossfader back and forth with everything from his chin to his foot. All while casually chewing gum.

European runners up, Mick Hansen and Guan Elmzoon, were equally as competent as each other, which is to say about 50 times worse than Cash Money.

You have to feel sorry for stand in defending champ, Joe Rodriguez, who was watching from the stage, ready to follow. The battle had already been won.

Watch Cash Money conquer the world here…

DJ Qbert

No one has done more for the image of turntablism than QBert - he’s to scratching what Bruce Lee is to kung fu. This one-man turntable philanthropist lives to teach the ways of the DJ, and will not rest until every man, woman and child has had a bash on the faders.

He came to fame rising through the elite San Fran DJ community, then the world stage throughout the nineties. His routines stunned everyone with their cavalier attitude, insane scratches and bulletproof confidence. Then, joining forces with Mix Master Mike and DJ Apollo, he scooped two world DMC titles and opened up the competition to team battling. (Rumours abound that they banned him for being ‘too good’).

World tours followed, and he built on his Turntable TV videos with the Do It Yourself tutorial DVDs (the Dummies guide to scratching), as well as the first ever full-length turntablist animation, Wave Twisters.

He’s now the dean of his own online Qbert Skratch University, and helps companies like Vestax invent new turntables (like the portable QFO with a built in mixer). In short, he’s the poster boy for scratching.

Think you’ve got what it takes to battle the Q? Try your luck here…

Battle records

Finding the deadliest sound effects, stabs, drum hits and vocal snippets to cut up has always been at the very core of hip hop DJing. It can make a Rap tune’s chorus take on a new energy (see DJ Premier’s choice scratch sections on his own Gang Starr productions), or be the knock out blow in a battle routine (“Do you want some of this?” asked Mix Master Mike of the X-Men. “’Hell no’, he replied”).

Back in the days, DJs would scour their record collection for clean punch lines, or full acapellas, and mark them up with stickers so they could find the dopest clips when they needed them in the heat of a mix.

People like Simon Harris and Norman Cook first thought about making ‘DJ records’ with breaks and scratch sentences on in the late eighties, but the boom came in the nineties.

More specialised and logical innovations occurred through the Hamster Breaks (1993 - the first modern battle record?), Dirtstyle, Super Duck Breaks, The Skip-Proof Scratch Tool and Clocktave releases, leading to the widespread technique of producing ‘locked’ grooves, all note scratchable musical scales, and sample-heavy cut sections on wax.

These essential vinyl weapons, with their goofy or saucy covers, would poke out of every discernable turntablists’ record bag, and be known inside out and back to front after heavy practice sessions.

Horny Martian Breaks? Check out Butchwax’s interplanetary scratch sounds here…

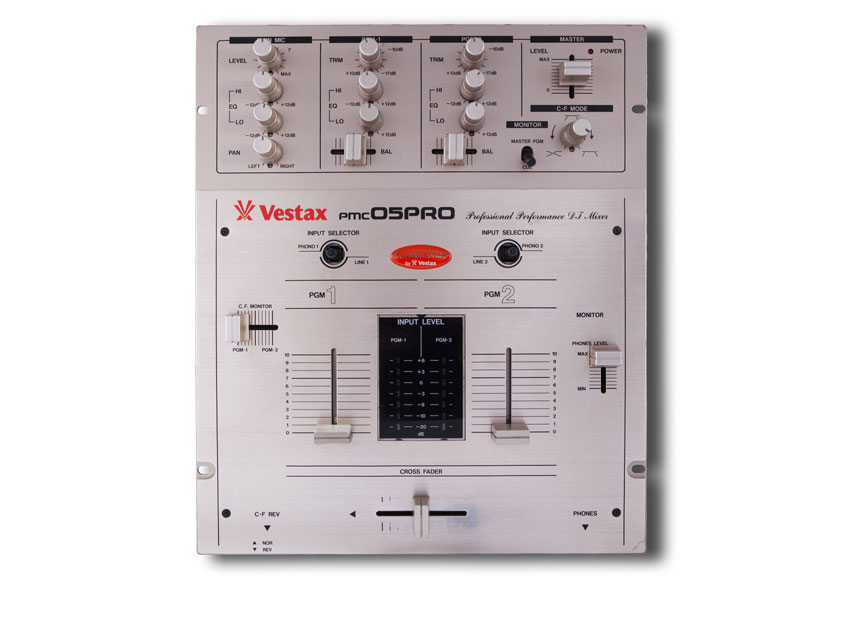

Vestax PMC-05 Pro mixer

There is a fine bloodline of pioneering mixers over the years, stretching back to old school hip hop icon, the GLI PMX9000, with its ‘transition control’ (or crossfader, as it would be known), to the fondly remembered Gemini MX-2200 series (the early battle mixer).

It was one make and model, however, that became ubiquitous with the golden age of scratching - the Vestax PMC-05 Pro.

Since its launch in 1995, it quickly became the favoured unit for turntablists all over the world. It’s as if they locked all the leading DJs of the day - Rhettmatic, Shortkut and Qbert - in a room and wouldn’t let them leave until they’d came up with the ultimate mixer (not far from the truth…).

It’s unfussy layout made juggles more fluid, the curve was super tight, it rocked the first exterior hamster switch, and it was without gimmicks (unlike the later Samurai PMC-05 Pro D, with its ’cheating’ triple-click dials).

Its battle DNA can be found in any serious contender to the throne to this day, including the hotly anticipated, and Qbert-endorsed, DJ Tech Thud Rumble TR-1S.

Let Yogafrog and DJ Qbert school you on the 05’s history here…

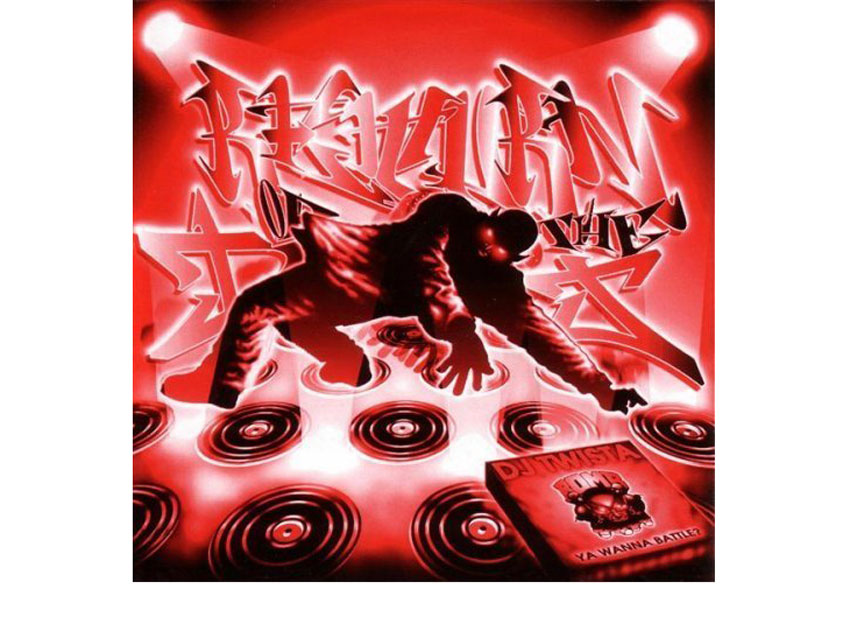

Return of the DJ Vol. 1

There was a time when the DJ on a hip hop album could only catch wreck on the chorus cuts. Or, if they were lucky, get a single track to show how they do.

The seminal Adventures On The Wheels of Steel by Grandmaster Flash, DJ Premier In Deep Concentration, and Eric B’s Chinese Arithmetic all showcased the DJ and his skill, but felt fleeting and isolated on these Rap-centric LPs.

It would take until July of ’95 for Bomb Records outta San Francisco to take the credit for putting out the first all-DJing project.

The tables had turned. The DJ had no need for anyone on the mic - They were speaking with their hands. And this compilation of some of the best crews and DJs in the scene showed that they could sustain the listener for a full album, and leave them wanting more (Vol. 6 out now!).

Full solo artist albums from D-Styles, QBert and Faust followed now that the DJ was recognised as an artist in their own right, and it proved there was market for turntablism as a genre.

Listen to the standout track, Invasion Of The Octopus People, by the Invisibl Skratch Piklz here…

Digital Vinyl Systems

Digital Vinyl Systems born out of the noughties like Serato Scratch Live and Traktor have gone on to overtake traditional vinyl-orientated set-ups. The sight of the DJ looking like they’re checking their email is more likely than seeing them riffling through a big sack of wax these days.

It’s rooted firmly in the world of turntablism too - Even the DMC softened up a coupla years back to let its competitors adopt it, and every last one does.

The advantages of a DVS are astronomical - instant doubles means no digging for second copies of records. No skipping. There’s no wear and tear. There’s no need to change the record, meaning faster transitions. And owing SSL gives every DJ the opportunity to create their own tracks and sample sentences, and lets them customise their ideas for any routine.

Is it cheating? Since about 2004 all battle DJs have opted for the 'whole routine pressed on one record' style of competing anyway. It does, naturally, allow them to construct their routine down to an airtight level, and that has been called soulless by the old school cats. Are they right?

No longer are we going to see Chad Jacksons flinging records over their shoulders. No more ‘sticker looping’. No more thrilling sentence juggles that made Noize’s sets such a high point of the art…

Whatever you potion, this is the here and now. Everyone from Z-Trip to Jazzy Jeff rocks SSL. DVS packages like that have provided the perfect transition from vinyl to digital for DJs who had learned their prized skills jockeying 12” singles. It does beg the question, though - whatever next?

Which of the top two DVSs is right for you? Let scratch legend Qbert be your guide…