Richard Devine interview

The one time Warp Records artist talks to FM about his new album and studio

Richard Devine

Yamaha DM2000VCM

Devine Modular

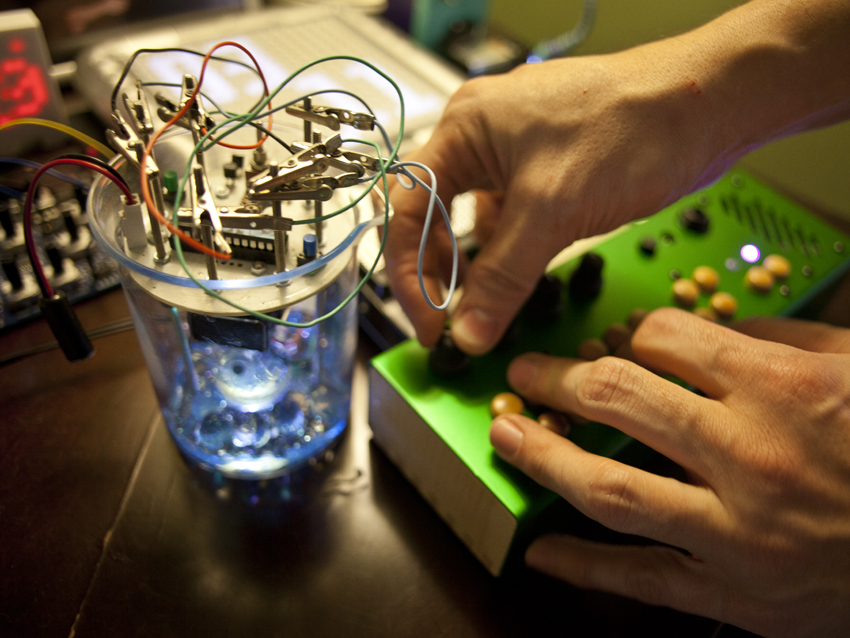

Devine hack

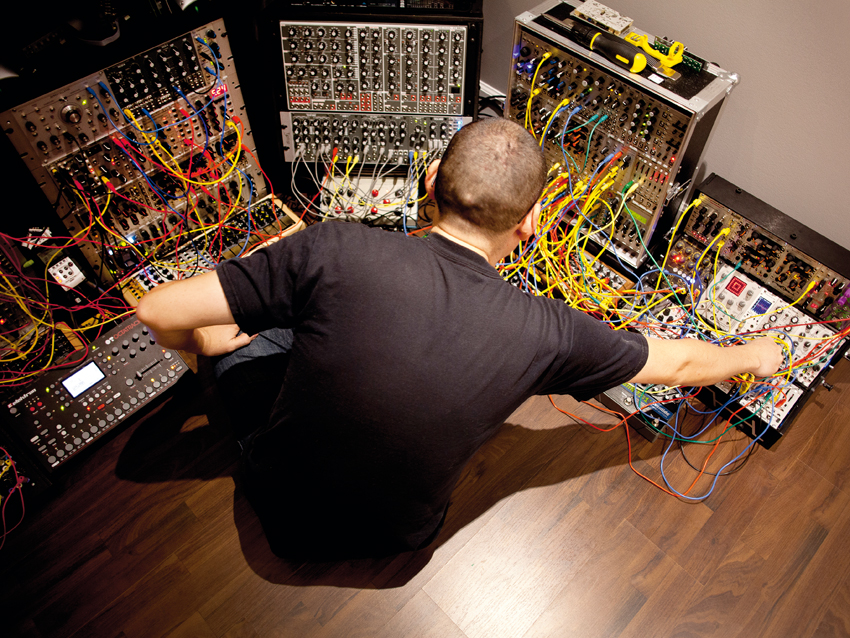

Devine at work

ARP 2600

More modular

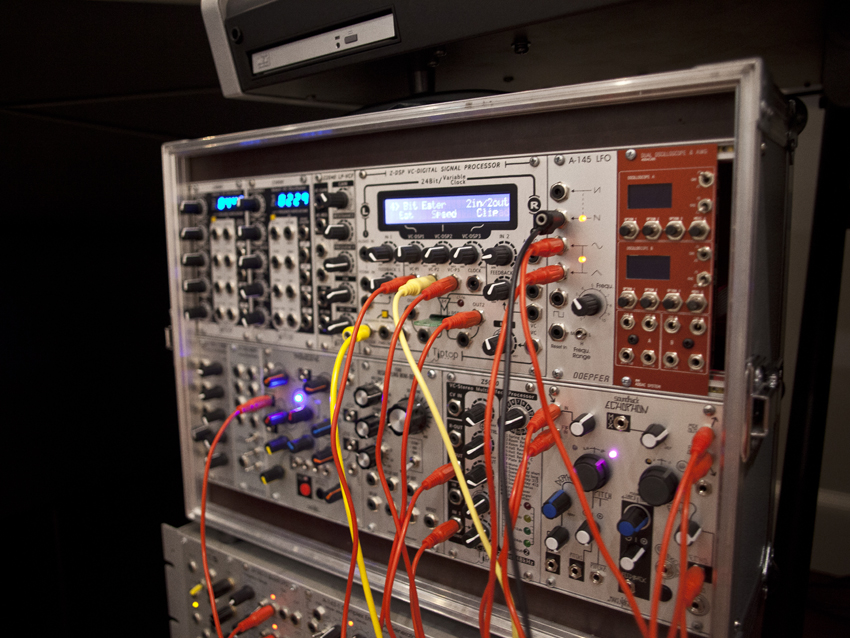

Modular side

TR-808

Virus

For a full ten minutes now, no one has focused much on the empanadas set out before us in the Latin American bistro we're dining at in downtown Asheville, North Carolina.

Instead, Richard Devine, his wife Amber, and synth pal Alessandro Cortini [Nine Inch Nails] have been talking about the new studio he's been spent months constructing in the quiet, leafy suburb of North West Atlanta where he lives and works. Despite the delays encountered during the build, that didn't keep the one time Warp Records artist from knocking out a new full length album, test driving whatever new gear was sent his way, and creating a sold out seven-inch for a new series based upon a boutique modular kit he's been experimenting with (see New Kids In Town box out).

Later, when FM are shown around the new space that occupies the lower level of his stylish home, we find the studio crammed with nearly a lifetime's worth of sound exploration. Columns of top shelf synths surround either side of his new Yamaha DM2000VCM desk and a tidy laptop set up commands a prime amount of real estate. As for the modular side of the room, it's a Jackson Pollock- esque spray of coloured patch leads. It's clear to see Devine is relieved to have reached this point in the project and eager to get on with putting together more of the weird and wonderful sounds he's been making since his student days in the early 90s.

Devine spent a fair amount of time when he wasn't at uni in Atlanta scouring second hand shops for gear. The strategy netted him his first ARP 2600 for $250. A chance meeting in the mid 90s while test driving solo material on the decks of an Atlanta club would get him his first release, the four track Polymorphic EP (released on Six Sixty Six). From there, other random encounters would net him deals on both the Schematic and Warp labels.

Following a surprise call from Mate Galic of Native Instruments, Devine began collaborating with the German company, in many ways launching his commercial sound design career. Full length releases followed but the joy of conjuring pure sound eventually won his heart. Now, his Devine Sound outfit has grown to do work for TV ads, tons of synth manufacturers, and even that Nook reading tablet you may have stashed by your bedside.

"You don't want to be chasing after something that someone has already done. Be unique. Start your own genre"

In December 2012, Devine released another full length album, titled RISP, on the label Detroit Underground. It's old stomping ground for him, with jittery Electronica music that comes off just as free-flowing and organic as it does mechanistic. That's because Devine crafted the sounds on the new record from patches built up on his wide range of modular gear - banks and banks of Eurorack kit used to lovingly coax his signature alien and robotic textures. While Devine is enthusiastic about all of his gear, it's plain to see it's those small, tweaky boxes that speak most to him these days...

Why does modular appeal to you so much?

"I was working in the digital domain for so long, I almost got burned out on it. Basically everything's calculated, everything's perfect, everything's coded. If there's any sort of deviation or randomness you have to actually program that randomness into the computer yourself, whereas on the modular it's kind of an open game. If you do something in the computing environment it will give you an error - you could crash a program - but none of those rules apply when working with analog and control voltages in the modular stuff. Some things will happen but you don't understand why. You're like, 'Oh, well. Theoretically that shouldn't be working but it's working somehow and it's outputting something bizarre and interesting.' To some people it might be useless, but I find it useful."

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Aren't you concerned about being able to reproduce it in a live setting?

"That's one of the things I love about it: I'm not able to recreate something exactly the same way it was when I first created it. You could get close, but it wouldn't be 100 per cent."

Was RISP about capturing moments like that?

"Exactly. Things that happened throughout the year while I was working on projects or different things. I would stop and work in the studio late night after I had finished up client work, and just patch up some stuff and come up with something that would happen randomly. I would be like, 'Oh, this is kind of an interesting idea. Let me see if I can improvise on top of this and add to it and make a composition out of this weird patch.' I love the whole idea of generating a patch. It almost comes alive. Like this little electrical floating ghostly organism that's existing in this realm for just a split second and then when you pull the patch cables out it's lost forever. Basically RISP was these experiments I had been doing on a modular synth. All of which were no computer, or maybe using just one piece of hardware, and seeing what I could do with that; seeing what new ideas and variations would come from the experiments I was doing."

How did you capture that?

"I have several different Intellijel mixers that I would mix some of the voices and outputs into, and then submix those and split out as much stuff as I could into my RME UFX card. On average I had about eight to ten inputs that I would record, and then I would slightly pan them and wouldn't do much. Iwould basically record everything dry. There are noplug-ins or post processing done on any of the tracks. A lot of it was happening pretty much in real time, and I tried to create patches that I could almost perform in a way so that they would already be doing their own thing. You could leave them andthey would do something really cool, running in kind of an idle mode, but I also wanted to be able to take things in and out, build things up slowly and change things. The tracks on the album evolved in a way where I could turn them into something like a musical track in their own organic looseness.

"You don't have the automation or the control you have in the computer. Everything is happening by hand and you have to let go of a little bit of control. This year, I'm implementing theintroduction of using the computer to control the modular stuff. With my new setup, I now have a whole host of MIDI to CV converters and MIDI sync clocking devices that will clock from my sequencer. I'll be able to send gate outputs from the computer into the modular at very specific times.rather than me just chaining up sequencers and seeing what happens."

What's the balance for you right now between sound design and recording music?

"It goes back and forth. I would say a good 80-90 per cent of the year I work on sound design client work. That not only includes working with plug-in companies and instrument design companies, but I also do a lot of work with advertising agencies and iOS developers.

"I've been doing a lot of work with iOS music making applications, and then it goes to working with companies for the actual hardware. Just a couple of months ago, I finished doing sound design for the Barnes & Noble NOOK tablet. I did the start-up sound, the logo sound, the out of box sounds, and the system UI sounds. I designed all the system alert sounds for different notifications, like the scrapbook sound where you attach something in your favourites category. I did design work for LG, creating sounds for their new LED televisionsthat are about to hit the market. Basically, they have developed this environment where there's a shopping mall inside the television. You can shop at different stores like Reebok and Nike, and I designed the sounds in the store and the navigation controls and the mouse clicks and stuff. There's a lot of UI-based sound, like tiny blips and bloops and stuff."

What's the attraction of sound design?

"I loved the idea of taking what I do and applying it to different fields. I was touring and had been making records for about 12 years, so I was looking for new outlets. I've always been adventurous and loved the idea of working in films, television and video games, and for different technologies where sound could be implemented. At the end of the day, I love making sounds so I wanted to focus in on that. It's kind of what I've been building up over the last ten years, working more as a sound designer. That's why there was such a long period from one album to the other."

When you're doing that type of work, are you ever tempted to keep a cool sound you come up with for an album?

"There might have been a few sounds here or there over the years, but for the most part I give it all away. I love to hear what people do with the sounds; hearing them used in ways I never would have thought to use them. It teaches me how to design sounds better in the future because I hear how they have been implemented in different musical genres, styles and approaches. It helps me to become a better sound designer, in a way."

"I get inspiration from art. I go to art museums. I like visual art, stuff that's not even in the realm of music"

So when it comes to working to spec, how do you approach it? For instance, what would you do if someone asked you to design a voice for one of the robots in a new Transformers film?

"I would read the brief and see specifically what kind of stuff they were looking for, and what kind of adjectives they're using to describe any sort of sonic traits. Then I would look for the best tools to help me create. Is it more vocalization? Is it more mechanical? Is it heavy? Is this a bigger character or a smaller character? First, I would make a list of these things on a sheet of paper, then I would probably go to the computer. The first part would be the voice, and then I'd decide how to process it andcontrol the voice. Maybe I'd articulate it with weird gestures and stuff, maybe use a Wacom tablet with my Kyma system or controlling sine waves using formant synthesis. Or I might use additive synthesis, pulling partials around. I would experiment. If that didn't work, I would maybe synthesize using something like the Nord G2 by doing phase vocoding through it. Basically, I'd just hunt around until I got something close."

So you're not tied to any particular approach?

"If I had to work with just a hand drum and a sheet of paper, that's what I would use. I'll use the cheapest toy or the most ridiculous thing to get the exact sound I'm looking for, but I don't have a heavenly piece of equipment that can do everything I want. There is no right or wrong way. At the end of the day, it's going to wind up in the computer to be edited anyway."

You must get plenty of inspiration being surrounded by all this gear?

"I get inspiration from art. I go to art museums. I like visual art, stuff that's not even in the realm of music. Or I listen to music that's not in the same genre as me. I find a lot of inspiration in acousmatic music like some of the early French, German and Canadian composers. There's stuff happening in electric acoustic music that's just so freeform as far as what can be done in a music composition.

"I also find a lot of inspiration through nature. I do a lot of field recording and hear things that make me go, 'Wow! Listen to the complexity of what's happening here.' A couple months ago in North Georgia, I recorded different species of animals from shrimp to bats with an echolocation recorder, which records the tiniest vibrations happening up in the 150-200k range. It's beyond what we can hear and I was blown away by some of the patterns. I couldn't believe how intricate, complex and strange it was when I looked at them on a sonogram. It looked completely alien."

What about remixing? How does your approach change to coming up with sounds?

"It depends on the remix and the material. I've never really approached a remix the same way twice.Sometimes I wind up recording a bunch of sounds before I start. I'll be like, 'Hmm, I know what I want the palette to sound like so let me just get my recorders and record a bunch of stuff.' I want to keep it all in the same sort of theme, and then I'll pick out the best pieces or what I call the 'audio Lego parts'. I integrate those into a structure, work up a remix of what I have, and pull out the pieces that really make up their track. Then I put in my interpretive piecesof what I think would be cool in those 'Lego' sections. So I guess I do a lot of stuff like that before I even open up a sequencer. I get the ingredients first. I go out and grab stuff that will hopefully inspire me. Sometimes it just magically, perfectly connects together."

"I'll use the cheapest toy or the most ridiculous thing to get the exact sound I'm looking for. There is no right or wrong"

Was that your approach to the Aphex Twin remix of Come To Daddy?

"I remember thinking that was such a balls out, rambunctious track everyone knows. What would I really be able to do with it? Aphex are already so amazing, what could I possibly do to make it better? So I really struggled on that remix. At the time, I was using half computer, half sampler to make that song happen and my computer at the time wasn't fast enough. I didn't have enough processing power to actually record that entire song in the way it was presented. I had to break it down into four different sections and then fill my sampler with as many sounds as it would take. Then I would record the first minute, max it out, then the second minute, max it out, and I'd be able to get about a minute and 20 seconds. Eventually I had to glue all four sections together to make up that remix."

At this point in your career, are there any musicians you would still like to work with?

"Man, there are so many. I really like the music on [Olaf Bender, Frank Bretschneider and] Carsten Nicolai's [German Electronica] Raster-Noton label. I really dig [Berlin based] Grischa Lichtenberger's stuff and I would love to work with [American Electronica composer] Morton Subotnick. I had a chance to sit on a panel with him at MoogFest and watch his performance. To me, he is one of the most important figures in terms of propelling me to where I am today with modular synthesizer and with my fascination of sound in general. When I first heard Silver Apples Of The Moon, in high school, it brought the fascination of sound to me.

"I have always had an emotional connection with music - it would either make me happy or sad - but very rarely would you find these sorts of fascinating discoveries when you're almost coming into the forest and discovering a new species of animal that's never been found before. There'snothing rhythmically you can immediately associate with any other kind of music, and that's basically when I heard Morton's music. It's very gestural and expressive and liquid and polymorphic and ever-changing. I was totally blown away. To me, it sounded like electrical, organic energy. The Make Noise record I released for the Shared System Series [see box out on next page] was basically a homage to Morton's early works."

Was that a challenge?

"Because it was seven-inch, we were restricted by a time line - you can't sequence anything that's going to start and end at a specific time [with the modular]. You're basically performing that piece like aninstrumentalist would play their part on the track. However, seeing how there was no real tempo to the track there are parts when it goes completely silent before starting all together, and then it builds up again. These two pieces were very difficult to evolve in a way where it felt as though it was a natural listening experience. It was very difficult to technically make all that happen within four minutes and 55 seconds, and yet still keep thisfluidity with things that didn't change too fast or took too long."

How often do you run into obstacles like that during your work?

"People and friends of mine come to me all the time and say, 'Oh man, I just can't finish this track. I have a good idea that I've started and I've been working on it for weeks and weeks but I've only been able to get one or two minutes in.'"You know, I've had the same problem before and I always tell people that the best thing is for them to just walk away for a little while. You know, whether that's a couple of days, maybe a couple of weeks, so that they can give their brain a rest from hearing the repetition of working on it so much. It's important because a lot of the time I can get so lost in working on 30 seconds of sound for one of my tracks that I kind of lose sight of the bigger picture. At that point, I run into a creative block and simply have to step away. Sometimes, stepping away is the very best thing to do. Just let your ears hear something completely different for a little while and then come back to it fresh."

Fair enough, but what's the best advice you have had from someone else?

"My good friend Josh said, 'Hey Rich, no one's going to do you better than you.' I will always remember that. You can't be like [some other artist]. Sure, you can sound close to them, but at the end of the day you don't just want to be chasing after something that somebody's already done, do you? Do something that hasn't been done. Be unique. Start your own genre. Start your own thing. It's simple to say but a lot of people lose sight of that, you know? Even if it goes against the grain [do it]. You might get a lot of people who say your stuff sounds like crap... I've had a lot of people who tell me my stuff sounds like crap but the thing is, I stuck with it because it's what I love to do. It's like, you should be able to walk into an art gallery and go, 'I know who this artist is. This is 'this' person's art.' That's how I look at my own work. I want people to know that when they hear my stuff, it's unmistakably, undeniably Richard Devine."

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.