Luke Solomon interview and studio tour

Future Music's guided video tour

Through his DJ sets, club nights, label releases, chart hits, productions and collaborations, Luke Solomon has made his mark on UK Dance music across the board over the past two decades. As a co-founder of Classic Records with Derrick Carter - the label that introduced DJ Sneak, Tiefschwarz and Isolée, among many others - and Freaks - the band that reached number nine in the UK charts with their dark bass-driven club hit The Creeps - his portfolio is vast and varied.

Luke's ability to transcend trends and remain independent while enjoying chart success makes him comfortable in his musical skin, trusting his instinct - a trait that, coupled with experience, landed him the role as Creative Artistic Consultant for Dance music heavyweights Defected.

Now he's back collaborating as Freaks, releasing another bass-driven gem in Black Shoes White Socks on Hot Creations last year, and is on the verge of dropping his latest solo album Timelines on Classic on April 29th. FM visited his home studio in London to get his story, his take on evolving studio tech and the state of the Dance music industry...

You started out as a DJ. What brought you into music production?

"Well I didn't grow up in a particularly musical family, it was more about art really - my mum was an art teacher and I went to art school, originally. DJing was something I just kind of fit into when I was studying and I wanted to start making tracks that I could play out. It seemed idiot-proof in a lot of ways to move into producing tracks as well as DJing."

What was your first studio experience like?

"It was with a guy called Rob Mello who's part of Classic [Records]. He had a studio with Zaki Dee in the Bus Space. Lots of outboard, Roland S-770 sampler, Trident desk, none of which I knew what to do with. I remember sitting in the room thinking about the capabilities and possibilities of what you could do with the equipment and there was something about it that captured me."

"From a Dance music perspective, I've always been inspired by what I played out, thinking 'How the fuck did they do that?'"

What was the first piece of kit you bought?

"I was working in a record shop at the time with Ty Holden and someone came in selling a Roland SH-101 for about £150. I bought it but there wasn't much else I could do with it, it was the only thing I had. It wasn't until I met Justin Harris [producer, DJ and one-half of Freaks along with Luke] that I thought I wanted to start making more music and buying more equipment of my own.

"John Marsh from The Beloved lent us an old Soundcraft desk, but we ended up using Matthew Herbert's Mackie desk. We'd been given things to help us along the way, which was nice. The scene was much smaller so we all swapped gear, discovered new kit from each other and became friends with the guys from Digital Village, which was in its infancy at the time. As we started to get money for remixes, we started to buy kit, a lot of the early Novation stuff - Bass Station, Drum Station, the standard things."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

And were those tracks always intended to be released, or were you making tracks just for DJing?

"They were always intended either for starting a record label or for another label. When I left the record store I was working for a label called Freetown with a lot of people who are now peers of mine like Robert Owens, Felix Da Housecat, Masters at Work and people like that. I was hearing all this music and a label called Prescription Underground came along that was owned by Chez Damier and Ron Trent. It was a life-changing moment and I thought 'I have to make something for this label'. It was a big ambition of mine.

"Rob Mello and me had a more definitive idea of what we wanted to do and that's how it progressed. It wasn't like it is now where you make records to put on well-known labels so you can gig all over the world - that kind of happened anyway. You worked at a record company, you were in promotions and people would always be booking you if you worked in that world. It was a lot smaller. We did a remix for Freetown, for Ashley Beedle and Ballistic Brothers, all friends of friends, within the community."

What was your role in the studio with Rob?

"It was mostly for my ears! That's why I was there. I wasn't as hands-on. I started to get my head around Cubase and the concept of having multiple channels and so on and when it came to final mixdowns, we used to do a lot of punch-ins and punch-outs and that's when I got involved.

"I knew when to bring in hi-hats, kicks, when to filter sounds - just using your ears. Rob guided meto a bit more hands-on and as a DJ that's what I brought to the table. Working with Justin, we built a studio at home and the first thing that really took me a long time to figure out was the [Akai] S950. It was so fiddly and not very logical. I slowly grasped the idea of MIDIchannels, multiple outputs, sampling drums and triggering them and so on. Oddly enough, listening back to it now, it sounds all right! I wasn't using any form of compression or sidechaining at all, it was just a case of 'That sounds good, that doesn't sound good' and so on."

"I think people believe they can do it all - buy the equipment, produce, start a label. You have to be a fucking genius to do that"

What were you sample sources?

"Anything I was inspired by really. Disco, at the time, was very much a staple of sampling - kind of like '90s House is now. The kids were looking back 20 years and harvesting the records. Freaks was very freestyle - we'd find the weirdest records to sample."

How did DJing inform your productions?

"From a Dance music perspective, I've always been inspired by the music I played out. Listening to early Masters at Work and Mood II Swing records, primarily the weirder, more dubbed-out things they used to do, and thinking 'How the fuck did they do that?' In hindsight I know they were mixing in big studios, with engineers and had a clear vision of what they wanted to do, so that was always inspiring Justin and me. I was also doing a regular Wednesday night with Kenny Hawkes and DJing on a pirate radio station called Girls FM twice a week so I was always buying music and very much a part of what was then a very small but new underground scene that was really inspiring. Hearing and buying all of this music would make us think 'Wow, let's get in the studio'."

Because this was a time when home studios were just becoming affordable and you mentioned there was a lot of sharing of equipment, was there also a lot of sharing of production techniques?

"I used to think it was ambition, but I actually genuinely think it's down to my attention span.[Laughs] I learn things quite quickly when I'm into something, but once I learn it I feel like I've got to move on. Part of the learning experience was pushing myself to work with other people, or pay to have something mixed in a big studio and sit in on it. For a while I thought maybe working with an engineer would give me a new perspective and let me focus on the tracks more, but all that happened was that I took it all in and thought 'OK I can do this myself now'.Ilike having the control of my music and what it sounds like."That's not to say collaboration is a bad thing at all, I like vibing off of other people, in all instances, with the label, with Justin and me and even with my solo tracks, I love other people's input. I think there are very few artists who can do everything on their own and be really great at it. Choosing who you work with, choosing how you work with them, choosing the equipment that's as much a vision as anything else."

Do you think nowadays you're expected to do it all?

"I think people really believe they CAN do it all - they seem to think they can go and buy the equipment they need, produce a record, start their own label and release stuff, all by themselves and I just don't think that's the case. You have to be an absolute fucking genius to be able to do something like that. Being great at something is a very unselfish thing - you have to absorb help from other people and look at other people's input into your music. Or have a massive ego and you don't give a fuck what other people think, and do it your own way - I've met people like that too and some of them have actually done all right! [Laughs] But they did it on terms that I don't agree with."

How did the track The Creeps come about?

"It was actually written originally as part of an album called The Man Who Lived Underground. We wanted to write an album about disappearing underground, removing yourself from society. It was kind of ahead of its time because it was before the advent of social networking! [Laughs]

"A friend of ours wrote a story and did an animation and we kinda wrote the music to an imaginary film. The Creeps was one of the songs, and was about a part in the story where a stalker was following a girl, so we wanted to write a bassline to reflect that - a very simple bassline. When we released the album ourselves Music for Freaks, it was just one of those tracks people gravitated to- Damian Lazarus, Steve Bug, people like that were playing it early on. We licensed it and Steve did a remix for Gigolo in Germany and that became the big underground hit. Then we licensed it again to Azuli and unbeknownst to us, they got Vandalism in Australia to remix it and that became the biggest download in DJ-download history at that time.

"It was the advent of Electro House and it became a benchmark remix and sound, so you can blame us for the horror that followed! [Laughs] Then Ministry [of Sound] stepped in and wanted to put a topline on it so we said we wanted to write it. It ended up going to number nine. That final versionwas the Vandalism mix, using his drums and the final vocal recording was done with someone else, but we did all the demos. So the final Pop version was a bastard son, three-times removed, from what we'd done originally."

Can you remember what the synth was for the bass?

"It was the Novation SuperNova - with layering for the bass, the mids and the highs. I did a lot of synth layering then, because now you have the plug-ins for adding octave layers and things like that - back then I just kept adding and adding until it sounded better. You end up having to do less EQing when you work like that though. I listen back to it and I can hear what we did 'wrong' at the time."

Who did you work with for your new album?

"I was in the studio with a guy called Peter Hoffman who's Richard's X's engineer and co-producer and he partially owns Miloco [UK-based studio group]. Pete's the person who helped me mix the album and I learned A LOT from him. Not so much about loudness, but how to get more volume out of things. You hear sounds in certain mixes that will come out of nowhere and sound so brilliant and defined and you think 'Why is that not triggering the limiter?' but it's because there's EQ involved and parallel compression, and techniques like that."

What was the key thing you took away from that music process?

"Probably learning to group drums correctly and to compress drums using the [Empirical Labs] FATSO. But the biggest thing I took away was 'Use your ears'. He'd be doing things that were crazy in theory but sounded great on the track. I'd have multiple channels for my bass sounds and auxiliaries with wet effects. He'd end up mixing the wet and dry sound together and adding more reverb and I'd be thinking 'You can't do that!' but of course it sounded great. Then, colouring things using certain outboard like the LA-2A and LA-3A, which I really gravitated towards. I use a lot of the UAD versions of those at home. I've had UAD since its infancy and I love it."

It's hard to be a producer without being a DJ as well. Is that harmful to both crafts? If so, what does the future hold?

Luke Solomon: "I came into this business when there was money, not just from DJing but from remixing, sales and all those things, to a world that's changed. Throughout my career I've had constant music revenue income and constant DJ income and one would balance the other. That's kind of tapered off and the DJ income becomes more relevant. So the record release process just feeds into the DJ gigs - you're not going to get any money from it but it gets your name out there. For me, I couldn't sustain that any more, I just didn't want to. I've got overheads - I've come from having money from music, having a family, getting older.

"The young kids have come up and it's interesting to see because the ones that are making it, that are making money, are doingreally well. They can afford to throw money at records, labels, have spare cash, don't have mortgages - it's this new generation of wandering maestros; wherever they lay their hat they can put their studio. If you've come from my generation it's a hard thing to keep up, unless you've planned really carefully for the future. Having said all that I think things are changing. The reason I know is that I've been hired as Creative Artistic Consultant for Defected [Records] so they can afford to employ me, and I'm over-seeing A&R and seeing that in established labels that have catalogue, the new digital script has started to kick in.

"People are finding it easier to go and buy music than steal it now and labels with catalogues are the first to see a return from digital music. I've noticed that remix fees from independent labels have started to increase, that there are advances again, things that are really optimistic. That world of 'you can do it all yourself, you don't need a label' seems like it's dwindling because there are so many people doing it. That also seems to influence the revival of vinyl because you end up with a tangible product of which there are less available, and therefore more valuable.

"The distribution companies at the record company level are becoming like A&R men because they can't afford to press records that won't sell. I feel like the next couple of years will be a transitional process where you can actually be a musician again and you don't have to rely on gigging four times a week or worry about being on the road all the time. I genuinely feel like those times are returning."

What else are you using in your home studio?

"I love the API [Lunchbox] - I can hear exactly what the pre on that [512c] does as a sound and it's amazing. An API desk is definitely on my wish list. One thing I've probably done more than anything else in my engineering career is record vocals. I've done it from a really rudimentary way, sticking a Røde NT2 into a TL Audio Ivory and not knowing what to turn on or off, putting too much limitingon, things like that. Now, I know I can run my Beyerdynamic [M130] mic into it and I know what I'm gonna get. Right now I'm working on a project called Mother Rose with a guy called Andy Neal. He's a really talented guitarist and has been for twenty or thirty years, and when we record we usethe shittest instruments, in the shittest environments into the shittest things; because that's the result we want. Like I said, when you're working alone, you tend to analyse and over-think it. When you're with certain people, and you just want to enjoy what you do, you can definitely hear that in the music youmake. The end process is something you couldn't achieve sitting in front of a computer screen with your hand on the mouse."

As an A&R and DJ, is that something you feel is missing in currently Electronic music?

"Yes, absolutely. That's why I feel I need to involve someone else, even when I'm making Dance music. You're getting a soul and a heart and something that's actually beating inside the music, instead of sitting with Ableton [Live] on a laptop with some headphones, using a lot of presets. There's not a lot of skill in that. There are very few artists who shine through and show they can do brilliant things in those circumstances.

"I had a conversation with Maurice Fulton way back and he'd sent me a remix he'd done for Classic and it sounded amazing - all this live percussion and various things. I asked him where he'd mixed it and he said 'On my headphones on the plane'. The reality of it is that Maurice is a talented man, has worked in big studios, has learned the whole process to know exactly what he needs to do inside that computer to make a record sound authentic and real, to make it sound like a lot of money, time and care had been spent on it.

"If you're learning on a laptop, and that's your only point of reference, it really limits you. I'm glad to see people are starting to invest in outboard gear and synths again. Things like modular synths are great as you can go out and spend 80 quid here, 100 quid there, and come out with something that no one else has."

How has running a label changed in 2013?

"Having people coming to me wanting to put music out on it again is great, but on the flip side there are a lot of DJs and producers out there who use the labels as a springboard to launch their own labels. There's not a lot of loyalty. Suddenly going, 'We've used you for what we needed, we've now got 100,000 Facebook likes so we're going to start out on our own. Simply having an audience isn't enough of a reason to start a record label. Everything else that surrounds it doesn't have the same definitive care and attention, and you're relying on that person being famous for long enough for that record label to survive. It's all about nurturing a family, a community, and having parties and a following. There's a lot to be said about that. Dance music is desperately looking for a community at the moment. It's fragmented, it's bitchy - I was watching Twitter yesterday and people who I know and have respected for years were arguing based on ego, over what's relevant, who's more important, who invented what. Dance music needs a community more than ever."

Don't forget you can catch Luke Solomon at our Producer Sessions Live producer event in Manchester on 28th September 2013.

Luke Solomon's new album Timelines is out now on Classic. Visit his official Facebook page for DJ dates and more info: www.facebook.com/lukesolomon

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

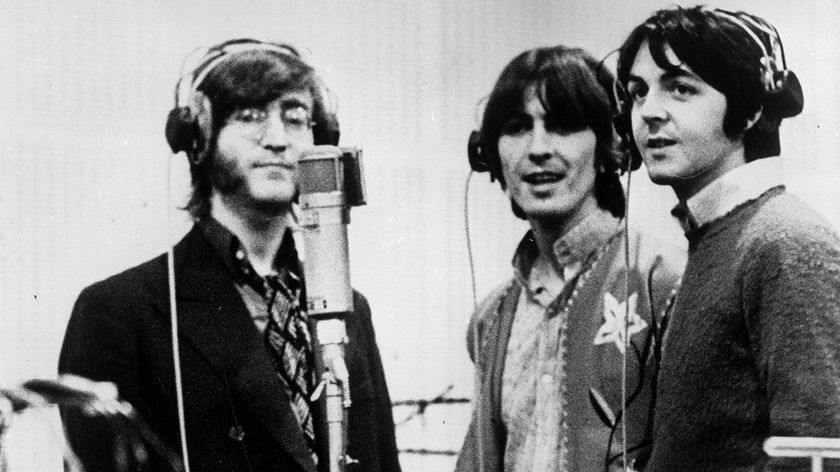

“I didn’t even realise it had synthesizer on it for decades”: This deep dive into The Beatles' Here Comes The Sun reveals 4 Moog Modular parts that we’d never even noticed before

“I saw people in the audience holding up these banners: ‘SAMMY SUCKS!' 'WE WANT DAVE!’”: How Sammy Hagar and Van Halen won their war with David Lee Roth

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)