James Holden on using modular gear live and Max for Live patches

"This way of playing has made me know that the next time I make a record I'll just do it live"

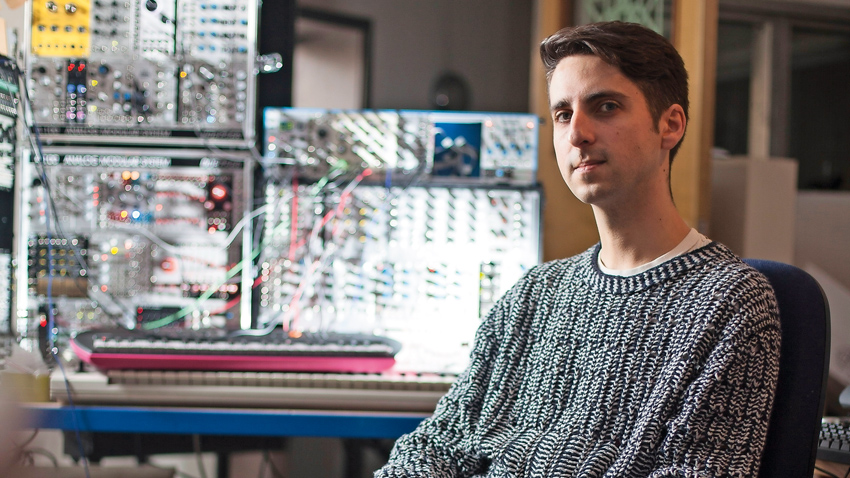

As the modular synth renaissance continues apace, we were delighted to visit the London musical nerve-centre of DJ, producer and long-time evangelist of all-things modular, James Holden.

Anyone familiar with Holden's spell-binding 2013 album, The Inheritors, will already realise that James has eschewed the Techno melodies which adorned his early work to mine rich new seams of experimental electronica. He has harnessed the drumming skills of (the equally brilliant) RocketNumberNine's Tom Page to create a compelling, frenetic live experience and they are currently in the midst of a tour, having previously supported the wondrous Atoms For Peace in the US at the personal request of Thom Yorke.

Having remixed myriad talents - from Radiohead, Depeche Mode and New Order through to Nathan Fake and Madonna - Holden also set up and runs his own Border Community label. A long way from his early triumphs in the DJ booth it may well be, but James Holden treats the modular synth as a performance instrument, albeit not one for the faint-hearted!

If you haven't heard The Inheritors, give it a listen, as it's a tour de force of sonic alchemy and illustrates perfectly the beautiful sound of modern modular synths. Try also to catch the live show, as 'one man staring blankly at a laptop' it most certainly is not.

Have the logistics of putting together your live show been stressful?

"It's been alright actually. You do begin to realise how much money for old rope DJing is, in terms of how much effort goes into it! The live show has much more that can go wrong than a DJ set but it's so much more rewarding in that you feel like you're actually doing something. Sure, you can improvise when you're DJing but it's only within certain parameters. Some of the surprises onstage that have just appeared in the air between me and the drummer Tom [Page of Rocketnumbernine] give you that feeling of 'what was that?' when you come offstage."

Are you recording all the live shows in case you come up with new material?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Not so much… because it's still sequences, it's still basically the original songs. But this way of playing has made me know that the next time I make a record I'll just do it live. The Inheritors was done live with me doing all the takes, but I think the next one will be done live in one take with me doing my bits and some other people doing their bits."

"You do begin to realise how much money for old rope DJing is, in terms of how much effort goes into it! The live show has much more that can go wrong than a DJ set but it's so much more rewarding in that you feel like you're actually doing something."

You mentioned earlier that your foray into the live fray owes a debt to Caribou…

"Yeah. I've worked really hard to be good at DJing and all the key-matching and I built my own controller, which was hard work and seems mad to give up on. I was making the records playing live on the modular but it wouldn't even work for, like, a whole day, as the way I like to work is making it all quite unstable and then riding that instability - having lots of feedback and stuff like that. That's nice in the studio where you can make a horrible noise for half an hour and then get to the good bit, but you can't really do that or be tuning oscillators onstage for ten minutes!

"So, doing the live gig with Caribou was a nice warm up, although it did fill me with the fear as I used my Doepfer case and the power supply isn't so stable in that one, so the stage lights would go on and all the oscillators would go out of tune, which was horrible.

"Then, Thom Yorke sent me an email just after the album had come out asking if I wanted to support Atoms For Peace in the States. I told him I couldn't really play live! Half a day later I realised what a mug I was being so said yes and had a pure stress month working out how to do it."

Again with the logistics?

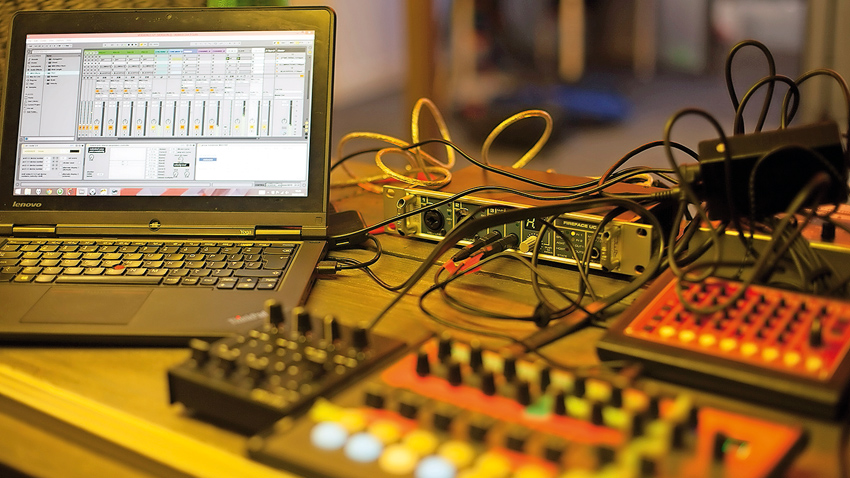

"I worked out some ways to solve it because the record is lots of layers of polysynths and initially I was thinking maybe I could take four Dave Smith Tetras or something to get those layers of polyphonic voices. None of that was really going to work as I didn't really like the sound of the Dave Smith synths too much anyway, if I'm honest. So, I came up with the idea of doing it in a hybrid way with Max for Live doing the things the computer is really good at and the modular doing the things that the modular is really good at.

It's not quite as wild as when the modular was doing the things that it isn't so good at but, because you can sort of emulate things you did on the modular in Max for Live, there's a lot of little chaotic systems, feedback loops and stuff like that. So it's still a bit unpredictable in the same way.

I have an Expert Sleepers module that gives you eight outputs into the modular, which I use most of the time. There's some switching around, but most of the time that's four polysynths with the oscillators done in the computer then the filter envelope comes out the other output and goes into a variety of nice filters. You can then route the signal into the filter cutoff as well to get filter FM sounds. Because the computer is controlling the envelopes, I have very sophisticated envelopes running rather than just basic MATHS AD ones."

The Inheritors is a real slice of modular sound, so Ableton gives you a modicum more control while keeping that integral modular sound?

"Yeah, exactly. To play Renata you need to have, like, 30-odd oscillators in tune with one another so you can't carry that on tour. Really, it took me a while to get good oscillators out of Max for Live but I just built up a little library of tricks and techniques to warm things up or soften them.

"I went through a few different types of filters before settling on these. Each one has sweet spots in different places, like Doepfer's Wasp filter does amazing feedback-distortion with the band-pass out back into it, which sounds brilliant. They're the thing that makes everything sound warm and good, so you almost don't really need great oscillators if you've got filters like that.

"For the bass, I use the Cwejman filter, which is amazing and just goes right though everything. That, with the 4MS [Eurorack Atoner module], which does sub-octaves under it… [laughs]. That's my favourite bit of the live set, where I find the sub-octave that makes the room rattle!"

Have you had a chance to check out the OSCiLLOT 'virtual modular' that's come out for Max for Live?

"I haven't seen it yet… For me, the good thing about the modular in the studio is the workflow and the way it's all under your hands - you're not on the computer. So I don't think I'd be that interested in it as I don't really use any software synthesis at all, apart from things I've programmed."

Why would you, really, when you have such an Aladdin's cave of modular delights?

"It takes as long to learn the good bits of someone else's soft synth as it does to program your own once you've been working in Max for a while. Then, if you have your own idea of quirks you want to create, it's much more fun to work that way round."

"For me, the good thing about the modular in the studio is the workflow and the way it's all under your hands - you're not on the computer."

Ableton's such an intuitive piece of software, isn't it?

"It is, and it's quite 'agnostic' in that it doesn't really care what you make in it. Sure, it leads you to make techno with the lego bricks you see in front of you, but it's not convinced that you should solely do that. It's essentially a MIDI tape-machine for me now really with some audio processing but it lets me have the tempo changing the whole time and doesn't fuck around with things in that."

So, Max for Live was the missing ingredient that allowed you to do all this live then?

"Yeah… Well, I don't know how I would have done it or learned how to do it before Max for Live. Also, it keeps going to next levels. For example, my synthesizer is in here and I've got it where you have all your parameters but not really any envelope controls. There are extra features like per-voice octave transpose on the Mono-Poly and retriggering and things like that built in. There's just an envelope shape on one knob, envelope amount on the other knob, then the envelope shape is set up in another plugin. So, across the knob on this setting you can go from a long attack, no release, through a spiky thing to a medium attack spiky sound.

"So, per song, I've chosen a range of envelope shapes that are necessary for that song just to pin it down. Otherwise, you've got four synths that need ADSR, cutoff etc for each of them! Then, for making things cross-modulate, I've got a sort of general expression slider, which pushes into lots of different things and then Tom, the drummer, feeds into a lot of things."

That's cool that you're bringing the live drums into the electronic domain, too…

"Initially we started off working on the track Gone Feral, which was originally made with just a clock pulse coming from the computer and everything else was trigger-delays and envelopes making all the notes. So, when we start playing that, the clock pulse comes from his kick drum and feeds. So, if I hit the kick drum it should be showing up on the Monome Arc OSC and then, eventually, that will turn into a noise.

"It was Thom Yorke who suggested I put the Arc on top of the case with some gaffer tape to hold it safe. It's the same principle as [Monome's] grid controllers in that it does nothing but you program it; there are beautiful, really accurate encoders and 64 LEDs.

"The original track was done with these Make Noise Maths going through a scale quantiser and, by changing the timing on the Maths, you get these arpeggios that aren't really timed on any clock measure."

Did you plan it all beforehand or was it a happy accident when you set Tom's drums up?

"Because of how I made the track, I kind of thought it would work, and also because the timing in it is quite loose anyway. So, not having a clock coming from anything, I've realised that it's one of the more fun ones to play live.

I've been working on this thing called a Group Humaniser patch for Ableton. Around the time I was making the album I read this Harvard paper about how human timing varies when people play naturally. I'd made a Max for Live plugin based on the paper that this guy had published and I mentioned it in an interview, which he read and consequently got in touch.

"We were talking and his next paper was more sophisticated, about how groups of people play together and there's this thing when you play together that you listen to every deviation and pick up on it. So, it's this chaotic, fractal system where the timing of one beat affects everything else that happens in the rest of the song.

"I've implemented that in Max for Live so you have individual agents, which are like a person playing, so each poly synth is a 'person'. The bass is a person and then Tom is a person so his input goes into the MIDI-trigger box, into another plugin in the computer, which feeds it into the same algorithm, so if he is a touch late on the snare it'll hear it and it can pull the Ableton clock back and forward. We only got it working towards the end of last year but Tom was like, 'I almost don't need the click anymore as I don't feel I'm having to pull myself back to the click as it's following me'.

"In this listening system, for example, if one of the synths is playing and it's got a sharp attack time then it tells the other synths that it's played the note when it thinks it's played the note. If it has a long attack time then the other synths hear it a little later and it hears itself a bit late so it tries to pull itself forward. So, when you pull the attack times around then all the synths react and pull themselves backwards or forwards in a natural way.

"Also, as part of trying to follow Tom's beat, the software is looking at patterns he's playing so, when he changes pattern or introduces a fill, it's also aware of that and can fire a signal to make a synth do a little ornament or a little high octave or something."

So, the aim is to increasingly humanise your machines?

"Yeah. It's not really like artificial intelligence or anything; it's more just making the pair of us, the computer and the modular rig into one instrument. So it's all connected and… you know, computer music can be so flat. In the old days, before I had modular, I'd spend so long putting LFOs on every pitch and timing error in by hand, and this now uses the science of what kind of errors are right."

How long did it take you to write the Group Humaniser patch?

"[Laughs] All my flights for a year! Aeroplanes are great for working on that kind of thing… It's really hard to work on something like that at home. I like the sense of community with the Max for Live thing. When I started out, the Buzz community was a bit like that. I feel that music should be about that kind of sharing of ideas… It's not a competition - it's just capitalism that makes it into a competition!"

What hardware are you using for the MIDI-triggering duties?

"It's the Roland TMC-6, which works great."

We can't help but notice a little ribbon controller below your Livid controller, too…

"This is brilliant… You've got position and pressure, but it goes through a scale-quantiser so whenever I use it I have different scales saved for each different song. I built a re-patching module for the setup so in each position it moves some patch cables virtually.

"So, in the first song of the set, the ribbon controller takes over one of these polysynth channels then comes back into the computer that way. In another song it goes through the Wasp filter, coming into the computer through a different pipe then through a reverb."

Has this come about through trial and error?

"[Laughs] Yeah… I did have those switchable multiples that Doepfer do but I was just getting confused and the wrong noise was coming out and whatever."

In the live environment it has to be said that there must be quite a lot of scope for pressing the wrong button or cable with a modular setup, no?

"Yeah, but quite often those moments have turned out quite good. Generally, I think the balance of risk and excitement is about right in this setup."

How does that lovely MFB drum-computer figure in the chain of things?

"Oh, that's directly connected to the Roland TMC through a MIDI-splitter and we're just using the bass drum and the snare on certain tracks just where they need that 808-type bass drum. These MFBs have such a good kick drum sound on them."

What are the main challenges of using modular synths live?

"I think I've solved them all, actually. The airlines are a pain; I have to go on British Airways otherwise I have to pay extra for the case. We took a KLM flight and something like 20 screws had come out during the rattly flight and one screw fell down the back, shorted out a bus and blew my 5 volts! I had a Doepfer MIDI-converter that I had to swap out because it wasn't working in damp conditions and I had the Make Noise Pressure Points, which didn't work when it was humid."

We had intended to ask how it all held up to the sweaty intensity of clubs and gigs..?

"It's been alright apart from one gig where this old MIDI-converter would drop to no volts. That was horrible! Other than that it's all been fine and I've actually broken more soundcards, MIDI controllers and computers in that time.

"At Field Day, the heat-sync must have come off the CPU on my old ThinkPad and it decided it was too hot so it would go to sleep! Luckily, I keep a spare for such eventualities.

"When we did the Atoms For Peace tour, Ryan from Caribou tour-managed for us. Caribou are the most perfect touring machine - almost like a communist system where everyone has their job and they all check on each other and help each other and everything's very balanced and incredibly well thought out. They've toured so hard that they know what might break and how many spares they'll need, so Ryan told me I needed to take a box full of spares for everything."

Tom Page seems like an ideal live collaborator for you. Do you feed off each other when you play live?

"Definitely… and the songs changed as soon as we started playing them together. Some of the songs had beats that were natural to me when I was high in the studio programming them, but they're not particularly natural to play as a drummer. In those cases I just thought it was right to let him find something natural and different rather than slavishly stick to what was done originally."

That Group Harmoniser patch must be a godsend to a good drummer like Tom?

"Playing to a click isn't fun for a drummer and it's hard and unnatural. The click is like playing with a shit musician who isn't really listening to you and just hammering along on their own. Even the arrangement of songs changes with having Tom there, and we're learning to communicate with each other as the arrangements can change between gigs too. Etienne Jaumet sometimes joins us to play sax live, too, so that changes things as well. Space has to be made for him or he inspires us to go off in a different direction. There's a language of looks and nods, which we've built up.

"I knew if I was going to replace DJing with this that it had to be real. I've seen people with modular onstage who just keep their backs to the audience and I didn't want that - I wanted it to be a performance. So, it was a lot of stress getting everything programmed for this and it took ages, but I had to do it and now it's just opening out more and more. The idea of taking this setup or a new setup based on this to get some new songs for a new album is really exciting."

How do you decide on gear for your studio?

"At the moment I'm playing around with the Cwejman RES-4 as almost a physical-modelling thing but the tone of it is very hard to control.

Is it important to you having your own Border Community imprint?

"Yeah, it is. It's a double-edged thing sometimes - there was a time when Border Community took all my energy and was almost holding me back as you had people doing melodic techno who didn't really want to move beyond that, and if I then move beyond that then the label's useless to them.

"I'm aware that a few years back I had a big audience who would be happy for me to keep doing melodic Techno bangers and I definitely could've made more money doing that; but I'm a bit embarrassed about how fortunate I am having this great studio space."

What's the spine of the studio?

"The computer is an Intel PC I made myself and I just got this Wacom monitor so using the pen for Max patching is super fast now. The modular rack up here was the whole album and I'm sure it'll be at the heart of everything for some time to come. The various keyboards, less so.

"I played the Prophet 6 a lot on the last album and it's still a keyboard that you come up with melodies on really quickly, but there's also part of me that doesn't want to just keep on playing saw waves through Dave Smith filters. I got this one in 5G in Tokyo [Aladdin's cave of synth gear] and it's part broken. Me and Luke [Abbott] worked out that one of the voice-chips has a dead oscillator so every sixth note is wonky. The guy in the shop was like, 'we can't sell this to you as you can tell it's broken', but I really wanted it. Having a quirk in a synth gives you different ideas."

Are you happy to see the resurgence in hardware and modular synths?

"It's great because there are so many modules and they're cheaper than they would be if there wasn't so much interest in them. It's still quite expensive and elitist - last time I did an interview and mentioned it someone called me an elitist. I think, in music, there is room for a bit of elitism; I only want to listen to good music. I've listened to a lot of shit music in my techno promo folder over the years… it doesn't make you happy."

Find out where you can catch James Holden live on his website.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

MusicRadar deals of the week: Enjoy a mind-blowing $600 off a full-fat Gibson Les Paul, £500 off Kirk Hammett's Epiphone Greeny, and so much more