In pictures: The Orb's Thomas Fehlmann's Berlin studio

One half of The Orb, Thomas Fehlmann talks writing, performing live and the latest album

Welcome

Born in Zurich, Thomas Felhmann has been an active participant in the electronic scene since the late '70s, having co-founded the German new wave collective Palais Schaumburg with Basic Channel creator Moritz Von Oswald.

Later collaborations included Sun Electric and 3MB, which resumed Fehlmann's association with Von Oswald alongside Detroit Techno legends Juan Atkins and Eddie Fowlkes. Fehlmann found further inspiration with his own Teutonic Beats label, and released numerous Ambient Dub albums on the Kompakt imprint.

That association continues to this day, with the German label playing host to The Orb's 13th album release, Moonbuilding 2703 AD, where Fehlmann once again finds himself in the production hot seat, alongside founding member Alex Paterson.

For the full interview check out Future Music 294 (August 2015), which is on sale now.

Concept album

“We didn’t really plan to make an album when we started working on the tracks, and the process was pretty unusual because we didn’t set ourselves a time limit and made two albums in-between.

“We actually made one big long-ass track, and it started evolving from there. When it began to have an interesting shape we decided to cut it into four pieces and come at it from a different angle, with one side being more ambient and the other we called the ‘entertainment’ side, which is groovier.

“The conceptual angle was set by the choice of the title, which was made pretty early on, then we came from a very different angle in the sense that we didn’t want to interrupt any new ideas that came into play by making a new track out of each new idea; it was just the one theme that we wanted to work from.”

Writing with Alex Patterson

“In practical terms, it’s only once a month or every two months that we can actually get together in Berlin and sit in the studio.

“It’s a pretty radical decision in the sense that we pretty much lock ourselves out from the world, dive into the work and let all our friends know that it is production time and we don’t want to be bothered by anything.

“When we work on a track we always do it together and never exchange files or anything as we feel the result is far more convincing and unique this way; and also it’s a way of working we should nurture.

“That connection has also evolved over the years through our connection with technology. These days, we feel we are very quick in bouncing ideas back off each other and that the technology doesn’t really slow us down anymore.

“I remember in the early days when we worked with Akai samplers, it took fucking forever to get something in time and in tune, and by that time we’d almost forgotten where the idea was coming from. In that sense, these days it’s much more automatic - I don’t even have to look when Alex comes up with an idea and he doesn’t have to explain it. He also gives me the freedom to pick up on his ideas and shape them into a track in the way I feel they could work.

“This has helped us to get speedier over the years, channelling the source of inspiration and going far deeper into the whole process.”

Working style

“It’s more like a tennis game; I receive his ball and try to make the best out of it, but I’m not trying to knock him [Alex] out when serving my ball back - just give him the ability to make something out of it before serving it back to me.

“For example, he’ll bring the sampling side of things, which is obviously just one element of the production, then I’ll add synthesizers and he’ll bring back something from his iPad that picks up on a certain bassline or sequence I did.

“So it’s pretty much an exchange; but from a physical perspective his place is more behind the decks with CD players and the iPad and mine is more at the actual desk working with the software.

“It’s not so much creativity versus technology; we both like to stay away from technology as much as possible because we think it slows our ideas down and detracts from creativity. We never expect a result; we like to be surprised and surprise each other.”

Creating a vibe

“In recent years we started to work live quite a bit, and this is very important because it’s there that we find interaction with the audience in its purest form.

“We’re fans of music and we buy records, but we’re not so much instrumentalists. We kind of train around that with our ideas and machinery and like to be entertained ourselves, so we take a close note of the audience’s reaction and whatever feelings are coming back from them.

“This has an influence as well, because then we know that in a live situation the music can develop into something.

“We very much enjoy this improvisational element when we play live because Alex rarely repeats something from one night to another. That’s something we’re excited by because we have found a way of understanding each other’s moves during the gig.

“I know just by the way he moves that now is the moment to bring something in or take something out because he might explode with something that needs some space. That keeps things very much true to the meaning of the word ‘live’ y’know?”

From studio to live performance

“Although we tried many ways of working like this and it didn’t always work that positively or naturally.

“I felt that at a certain time in the process of our development I was disturbed by doing something in front of Alex or that he was either taking out or confusing the subject of the tune. But, over the years, I learned to really embrace it and feel that as much as we gave each other freedom in the studio it should also translate to playing live.

“I had to find a way for each idea that comes from him to be treated positively so it would enhance rather than disturb me, which requires a process of letting go and saying yes to unexpected improvisational movements.

“I’ve never felt more comfortable with Alex on stage than these days. Without trying to exaggerate, it was three or four years ago when we really stopped trying to be louder than the other and actually embraced what other ideas were coming in.”

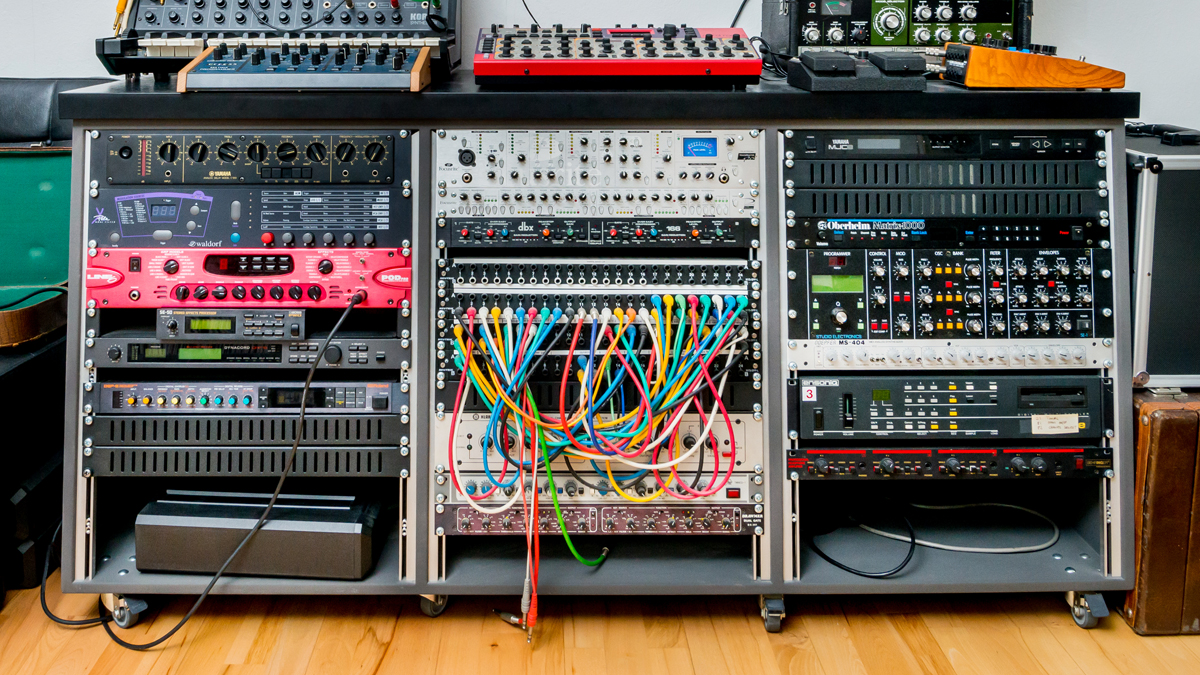

Studio setup

“I decided to have my studio at my flat. I installed a soundproof room so I’m not bothering other people in the flat above or below, and can work pretty much at any hour of the day, or whenever we feel like it.

“This is a very relaxed situation where we bounce back between the kitchen and the studio drinking litres of tea, and I feel it is the most convenient way to recreate the studio environment.

“In the early days, when you had to go in and rent a studio, you had to prepare and know that today was the day you had to deliver, which was always a little stressful and inhibiting. I wanted the biggest contrast to that as possible, which for me was to have the studio in my flat.

“In the studio itself I have a selection of gear I’ve been assembling over the years. There’s not a ton of it, but I still have a big Soundcraft analogue mixing desk and my first synthesizer, which I bought in the late ’70s, the Korg MS-20.

“Between those, Ableton Live is the main software we use for production, and a few effects that I use on the old-school analogue side, like the Roland Space Echo delay. We’re not so much into new gear because we feel the music is within you, not the machines.”

Wired up

“We have a 16-channel audio interface, which is separated quite a bit from any ideas we have in the box.

“Hard disk recording might be at the start of the process, then hardware overdubs come as a result of where we feel they should be added - and that’s mostly outboard, exclusively from my synths.

“I rarely record the synths until the end of the production as I always want to go back to using the filters and knobs so that I can interact and tweak them to recreate that live feeling after the final mix.

“On the other side, a very important part is recording Alex’s ideas as samples onto the hard disk and mangling them with Ableton Live so we can chop them up in what is a very quick process.

“The chronology is not so much hardware then software then mixing, but all levels at all times.”

Sound source

“We do field recordings quite a bit; just the other week when we were on a tour in America I sampled quite a bit - but I use the word ‘sample’ more out of convenience.

“These days, for example, when we use something from a record it’s always developed and processed in a way that even the creator of the original would not recognise it anymore. It’s not like in the early days when you would use a riff or a certain loop that would go on for a bar or two.

“It’s actually quite interesting the way we might use a hi-hat or a snare from a sample, because we like it to be a little bit ‘off’ and give it a life of its own.

“Working with Akai samplers was comparatively tedious, whereas Ableton’s open structure, in terms of what it allows you to do, means you can get accustomed to your own tricks until they eventually become part of your vocabulary.”

Plugins

“Trying to be honest with you, I’m thinking of what software synths we used on the album.

“There is a collection of Arturia old synths - like the Moog ones and the Arp, which I use now and then, but it’s not something that is a main feature; it’s more of a colour.

“In terms of realism, they’re getting closer and they certainly have the advantage of not taking up as much space in the studio [laughs].

“For synths, it’s usually more outboard. I’m happy to say that I use a lot of Nord Lead material - I have two of those. I also have two Korg MS-20s, and I use the Fender Rhodes quite a bit and an Oberheim OB-8.

“Gear is almost secondary these days, not so much in the sense that I don’t love them dearly - they’re part of my music-making thinking, but we’re not gearheads. We look for the flow of the production, using whatever enables us to do that.”

Modular synthesizers?

“They up too much space and time. As I said, when working with Alex I like to be very spontaneous in reaction to what he does - because he obviously gets bored having to wait until I make a decision.

“This was sometimes a flaw with earlier productions, where you’d get bogged down with finding the perfect sound.

“The lo-fi movement of 10-15 years ago freed us up quite a bit from this fashion of the quality of sound, so we felt that, at long last, we could just go with what we felt and be inspired in the moment.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.