In pictures: Max Richter's Oxfordshire studio

The gear that drives the neo-classical composer's work

Songs from Before

Influential neo-classical composer Max Richter has long operated between the folds of contemporary classical music and the electro-acoustic world. His prodigious output is strewn across opera, ballet and film and regularly bleeds into alternative popular culture, through his own work and numerous challenging collaborations.

With a back catalogue that has produced a rich stream of post-classical and ambient electronic music, Richter is a master at seamlessly entwining orchestral and electronic sounds – from his landmark debut album Memoryhouse in 2002 to his most recent release ‘from SLEEP’, an eight-hour experiment in ambient drone for people to, quite literally, sleep to.

Richter has recently taken his Sleep concerts on the road, with a trio of all-night performances in Berlin. This month, The Max Richter Ensemble embarks on a UK and Ireland tour performing a much shortened version of the album alongside a 10-year anniversary revisit of his melancholy 2006 album, Songs from Before, whichis out as a deluxe vinyl reissue.

As we recently discovered, in the studio Richter prefers to adopt a refreshingly simplistic setup, utilising a resourceful blend of analogue and digital technology…

No sleep till…

Last time we spoke, you were taking your eight-hour Sleep concerts out on the road – how did that go?

“It was great actually. You have ideas about it how it could work and what the audience would do, but until you actually do it, it’s all just theory. We started the gigs at midnight, the audience turned up and… went to bed [laughs].

“They mostly slept through it, but some were obviously awake and listening or doing yoga. The feedback we had was quite humbling really because the audience seemed to respond to it in a very emotional way. It brought out lots of strong reactions, with people thinking about mortality, friends, relationships and kids.”

Did you perform for the entire eight hours?

“I was probably on stage for about 7 hours. I had two or three little breaks where I’d run off and get a sandwich, but was playing the piano and dealing with the computers pretty much the whole way through.

“You have to get jet-lagged in a way, so that you’re in the right time zone to do it. The first night was really hard, it felt like climbing Mount Everest, but by the third night we’d got used to the architecture of it and it seemed to go by quite easily.”

Taking note

What software packages did you use throughout the production of the album?

“I use a trashcan Mac, which does all the heavy lifting, but the central writing environment is done using Logic and Sibelius. Logic is a workhorse than can do lots of stuff. It deals with all the electronics and instrumental mock-ups for movies.

“Sibelius is really good at getting clean notation out of musicians. Logic alleges to do notation, but it really doesn’t, and those two things talk to one another reasonably well.”

Are you a big fan of software plug-ins?

“I use a big mix of stuff. Kontakt is the mothership and that hosts a lot of different things. For orchestral music I’ll mostly use Spitfire Audio, because it’s mostly recorded at Air Studios. They use the same musicians in that room that I often record with, so it has the same sonic fingerprint.

“Then there’s all the Native Instruments stuff running within Kontakt, and I also use Reaktor. In terms of plugins, it’s mostly the UAD stuff like Soundtoys and some of the Sonnox products.”

Starting early

Are you enthused by the latest software innovations?

“Totally. As a kid, I learned piano at music college and went to university for my classical training, but that ran in parallel with my obsession with electronic music. I got a soldering iron and built my first synthesizer out of components when I was 13, so I’ve always been interested in new ways of making sounds and exploring that sonic universe. It’s an important part of what I do, and obviously a lot of that stuff has now moved into the computer.”

Do you still physically make things?

“I haven’t for a while because it takes a little time, but I want to start again. I love vocoders and have one that is kind of dying, so I thought that would be a great thing to build next.”

Always go for the real

Working within the classical and electronic domains, what’s your take on how digital is able to replicate acoustic instrumentation?

“In film scoring there’s this funny phrase that people say: “The demo sounds just like the orchestra, until you hear the orchestra”. Sampled orchestral libraries are getting really good, but even a fantastic sampled orchestra sounds terrible compared to the real thing.

“It’s amazing how big that gap still is, and I’m all for that gap existing because that’s how musicians make their living. It’s not just about sounds being organised in time, it’s also intention and thinking.

“If we think of the orchestra as a piece of technology, you’ve got 500 years of R&D there, so it’s no wonder that it’s better, more evolved and more responsive. Given the choice, I would always record real instruments.”

Problem solved

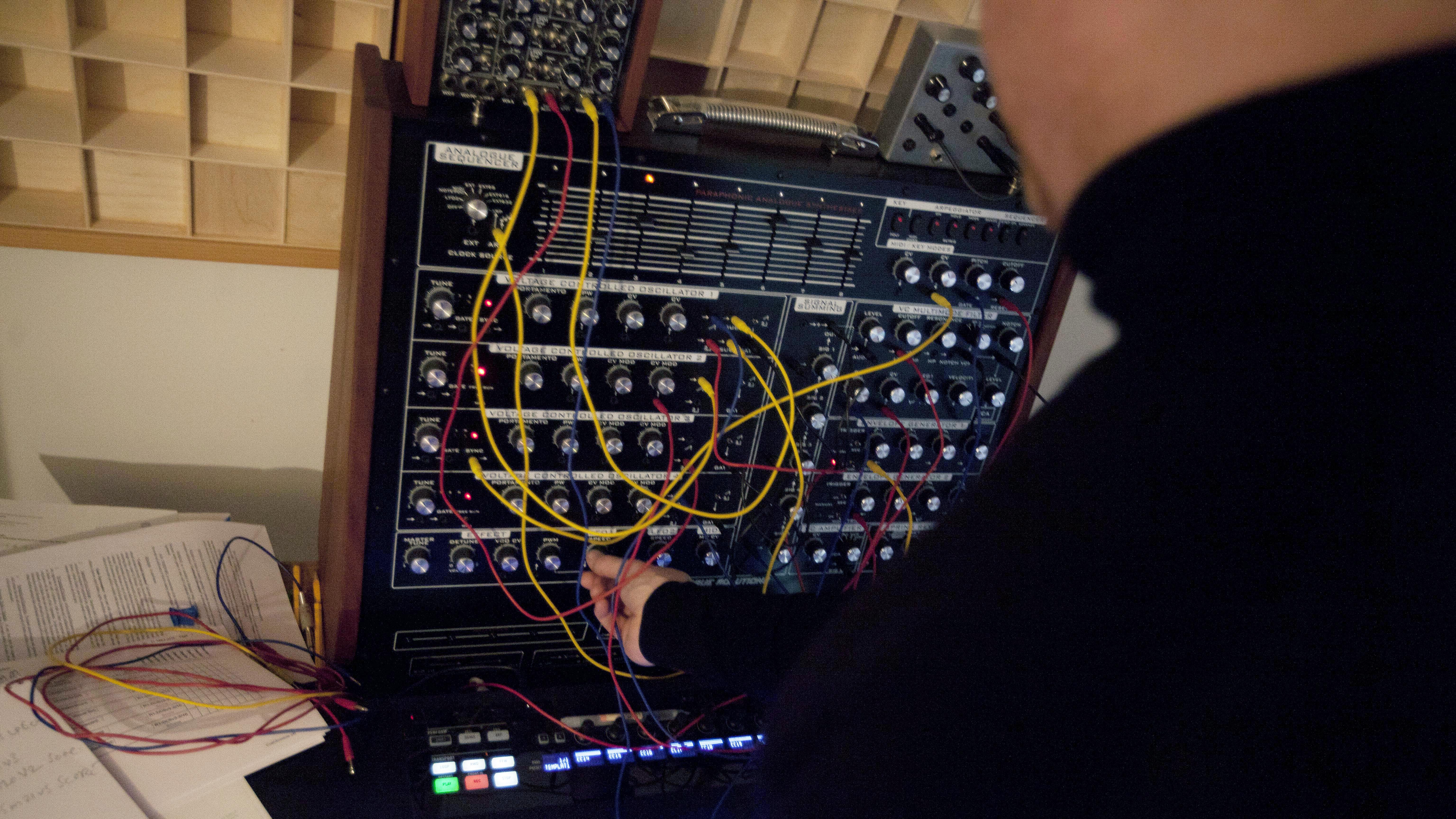

You have a Polymath Modular Synth with Sequencer and Arp?

“It’s an Analogue Solutions synth from a small synth builder based in Biggleswade. They basically build stuff to order. It’s a paraphonic synth, so four oscillators going through one filter, and it has a built in arpeggiator and a few other things.

“It’s a great synth and I’m very fond of that architecture because it’s a way of getting a polyphonic synth without an insane amount of patching, and it makes sense with everything going through one filter.”

Is it difficult to sequence modular through the Mac?

“Getting the synthesizer and the computer to talk to one another is always a bit of a challenge. Obviously you’ve got the usual MIDI to CV interface questions, but the Analogue Solutions actually has a MIDI-In on the back, so you can actually clock it from Logic’s sequencer quite easily.

“Unfortunately, that’s always an issue when you’re trying to get digital and analogue systems to make noise, there’s a bit of head-scratching involved.”

Textural preference

These days, do you have a preference for modular over digital?

“Well they’re different things, but it’s also horses for courses and it’s also a question of taste. Some people love that shiny, clean, in-the box sound and some prefer a more organic, rougher, alive kind of sound – so it really depends on what story you’re trying to tell and the context of the project you’re working on. It’s a little bit like the recording to tape question, it’s just a textural preference.”

Tell us about your Minimoog Voyager XL?

“That’s a great synth - it’s the latest incarnation of the Minimoog. It’s analogue in terms of the audio circuitry but has a digital control system, which is just about storing patches. It scans all the controls and you can save them, which is very handy.

“It’s got some patchability too, so the architecture is open in a way that the original wasn’t and you can be can quite creative with the way it’s structured. It’s still a monophonic synth and it has a ribbon controller, which is great.

“It works a little bit like an Ondes Martenot - you can patch it into a cut-off frequency, a filter or a resonance and play with the ribbon by sliding your finger over it. It’s a very physical and immediate way to interact with sound.”

Doepfer-rich

What other analogue hardware do you have?

“I’ve got a Doepfer MAQ16/3 MIDI analogue sequencer, which is just a straightforward sequencer for controlling any of the synths I’ve got. It’s got a couple of band pass filters, which I’ve always liked - it’s just like having a lot of different Bel filters, which you can turn up or down. It’s a really nice way to shape sounds – like a very fancy EQ.

“I’ve also got Doepfer’s Dark Energy, which is a monophonic synth in a little box.”

Droning on

I presume you use the Grendel Drone Commander for a lot of your ambient sound generation?

“That’s a great synth. There’s a sub-genre of synths called drone synths; you switch them on and they just drone. You can change the pitch, whatever the filter’s doing and the LFOs just by changing the controllers, but basically it’s just on and it drones.

“I used it a lot on my album Sleep because it’s warm and simple but it’s also very inexact, because it’s analogue things comes out differently the whole time. The pitch wanders a tiny bit and the filter isn’t rocked solid, so it just adds a liveliness and unpredictability in reality to sounds, which you tend not to get in the digital domain.”

Tools for the job

You still have a lot of outboard rack gear, what do you most often turn to?

“It depends on what I’m doing. If I’m doing a movie, then the workflows are so fast that you tend to be much more in the box until it gets to recording – then we try to mix in analogue as much as possible. On the records, it’s not 100% analogue outboard, but much more so.”

Reverberations

What reverbs do you favour?

”If I have time, the reverb I use most is the TC Electronic Reverb 6000, which I think is the best reverb ever in the universe [laughs]. You’ve got to hear it, and then you’re like “Oh! That’s what a reverb should be like”. But you do have to get a mortgage to buy it, it costs about £5,000.”

How do you justify the cost?

“On a film, reverb is really important because you’re telling a story about a space, so it needs to be really precise. But I also use Altiverb a lot, which is a game changer. I just think its recreation of space is better. There’s lots of modelling reverbs out there, but Altiverb just feels more natural and if you A/B it with the actual gear, it pretty much sounds as good as the real thing.”

Max is currently on his UK and Ireland tour performing 'From SLEEP' and music from The Blue Notebooks, with some tickets still available. More information can be found on his website.

- May 14 / Bristol – Colston Hall

- May 17 & 18 / London – Barbican Centre (SOLD OUT)

- May 19 / Norwich – Norfolk & Norwich Festival

- May 21 / Manchester – Royal Northern College of Music (SOLD OUT)

- May 24 / Edinburgh – Usher Hall

- May 29 / Dublin – National Concert Hall, Dublin, Ireland (SOLD OUT)