Don Was's top 5 tips for producers

Plus, producing Vintage Trouble

Intro - Vintage Trouble and 1 Hopeful Rd.

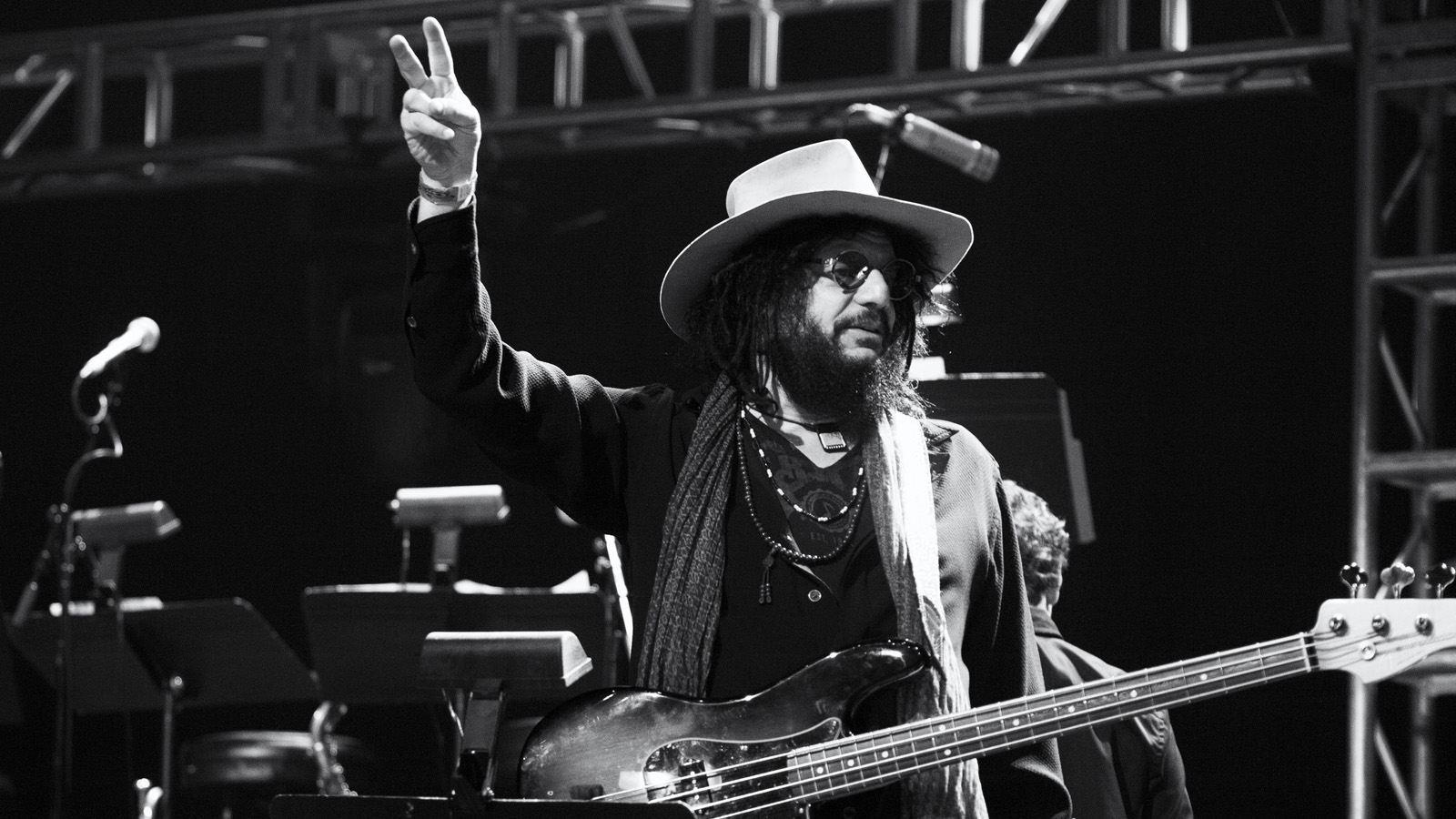

Since 1980 - when his funk-disco-jazz collective Was (Not Was) first burst onto the scene - bassist, multi-instrumentalist and record producer Don Was has sprinkled his magic on a quite simply phenomenal number of classic records.

A three-time Grammy Award winner - including Producer of the Year in 1995 - Was’s production discography is packed to the brim with top calibre artists covering just about every musical genre you could feasibly imagine: The Rolling Stones; The B-52’s; Bob Dylan; Roy Orbison; John Mayer; Van Morrison’ Lucinda Williams; Elton John; Bonnie Raitt; The Black Crowes; Ziggy Marley; Stone Temple Pilots; Neil Diamond; Brian Wilson; Richie Sambora; Ringo Starr; Glenn Trey; Iggy Pop…. the list really does go on and on.

In 2012, Don was also made president of one of the most prestigious record labels in the history of popular music, Blue Note Records, famed for the incredible jazz recordings it has presided over since its inception in 1939.

Before he runs us through his 5 top tips for producers, Don spares a little time to give us some insight into his production approach for LA soul troupe Vintage Trouble’s superb sophomore album 1 Hopeful Rd., released on Blue Note earlier this year to significant critical acclaim.

How did you first come across Vintage Trouble and what made you see them as a perfect fit for Blue Note Records?

“You know the actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus? She was in Seinfeld and she’s in this show Veep, which just won an Emmy. Our kids went to school together and they played on a volley ball team together and she came up to me at one of the games and she said, ‘I was on the David Letterman show last night, and there was a band on there and they’re perfect for you - you’ve got to check them out!’

"That was the first I heard of them and I totally got it straight away. They’re for real. They are genuine soul. First time, I went to see them live and saw Ty [Taylor] sing, I thought, ‘Man, this guy is fucking for real! He's not imitating Al Green, he’s not imitating Otis Redding, he’s not imitating Marvin Gaye…he's got his own way of doing it!’ and - if you look at him - every inch of his body is into the song and radiating the message.

"I think he's one of the great soul singers of all time. At Blue Note, when I first got the gig, the idea was to keep the label moving forward and not just simply trade in our legacy. And, actually, the guys that started the label in 1939 wrote a little manifesto that laid it out very clearly.

"It wasn't so much that they were locked to any style of music, or it had to be a certain type of jazz - what they cared about was authentic music. And I thought 'Well, fuck man, this fits the bill!’”

Did you immediately have a vision of how the album should be approached from a production perspective?

“Well, another thing that totally knocked me out seeing them play live a few times was that they were getting up in front of audiences who didn't even know all the songs… and they had them enraptured and dancing, and they didn't lose a single person. The energy just kept rising and rising and rising. That's a real gift to be able to do that.

"So, the first thought was, ‘We have to capture who you guys are. Let’s not necessarily doctor it for the sake of getting on the radio. Let's make sure you’re introduced to the world as who you are’. At first, I didn’t want to produce the record because I thought it should be someone younger than me. But then we started meeting with a bunch of different producers - all of whom were really good and all of whom make great records and had very wise things to say - but, for the most part, it simply wasn’t a reflection of who the band was. It was someone's vision of how to get them on the radio.

"That's the number one crime committed by a record company, when they sign a band because they love them and then they immediately try to change them. It happens all the time and it's the death of a lot of bands.”

So what was the next stage in the production process?

“They wrote some new songs and I went up to the rehearsal room to hear them and it was a tiny little room, maybe 10' by 10'. It was really packed in and really loud and there was no sitting back from it. If you're sitting in the room, you're in the middle of the band… and it just sounded so fucking great!

"And I said, ‘This is how the record should sound. This sounds so good to me sitting here right now, this is how we should do it!’ So we did a little bit of pre-production to try to capture the sound of the room and we put three mikes up. And that was based around a conversation that I and some other guys had had many years ago with Sam Phillips.

"Someone asked, ‘What mic did you use on Scotty Moore's guitar?’ And he looked perplexed. He said, ‘There wasn’t a guitar mic. I didn't mic the instruments, I mic'd the room. I’d walk around and hear where it sounded good and - in those spots - I’d put a microphone there.’ So Scotty Moore's guitar mic was also Elvis's vocal mic and that also picked up the bass and the drums. Those records sound so good because of that, because it feels like you're in the room.

"So, I thought, ‘If it sounds great in this room, then let’s do the same.’ We rented three RCA 44s and we put two in spots that sounded good and one kind of in front of Ty and we recorded for ten days. It sounded really cool so we said, ‘Okay, now let's go and do a studio version of this approach.’ So we went down the hill to EastWest Studio 2 which is one of my favourite rooms.”

And so you cut the actual album in a similarly live fashion?

“We just set up exactly the way they were set up in the rehearsal room. All in one room, very few baffles, and many songs cut without headphones. We had speakers set up so everyone could hear vocals and occasionally we used headphones… but the idea was just to replicate the sound and the feel and the relaxation of the rehearsal room.

"Everything was cut live including Ty’s vocals, which isn't to say he didn't come back and re-sing a couple of songs, but not every song. We were going for it with the vocals, although there was a little bit of iso around him so that we could keep the live vocals.

"It was great. We just tried to capture the sound of that band in that room and we used a great engineer named Howard Willing, who I've made a number of records with. He's a lovely guy and a great engineer with a great ear. He’s made a lot of records in that room so he knows the room and the board and set-up.”

Vintage Trouble are currently on tour in the UK and their new album 1 Hopeful Rd. is out now on Blue Note Records.

- Tue 10th November Manchester, The Ritz

- Thu 12th November Birmingham, The Institute

- Fri 13th November Sheffield, The Leadmill

- Sat 14th November Scarborough, Spa Grand Hall

- Mon 16th November Bristol, O2 Academy

- Tue 17th November London, The Forum

1. Be grateful for the privilege of being able to make records

“It's not a God given right. It can be taken away from you just as quickly as you got it, so - while you're in the studio, man - stop and smell the roses! It's really cool to make records and be in a room with a bunch of great microphones.

I love the look of cables plugged in, the microphones and wires running all over the place, and boxes of gear everywhere

"I just love the look of it. I love the look of cables plugged in, the microphones and wires running all over the place, and boxes of gear everywhere. And, here in LA, you get to work in some of those rooms that have such incredible history to them.

"I remember being a little kid and wanting to do this and now I get to do it. So, yeah, never take it for granted.”

2. Nobody ever bought a record because the snare drum sound was awesome

“In your role as producer, don't forget to look under the hood… and make sure you've got some good songs too! It’s pretty clear. If you don't have songs, man, you don't have a record.

If you don't have songs, man, you don't have a record

"Sometimes I've gone to mixes at times and a guy spends half the day getting a snare sound. I don't even know why people put the drums on first. That scares me. You know, if there's a singer in the band, why wouldn't you get the voice sounding great and add the other stuff to it?

"I know that's a rhetorical question and I know the answer but, sometimes, I think it's easy to lose sight of the most important things on a record. How cleverly you miked the snare drum may not be the thing that touches people's hearts!”

3. Keep the positive energy flowing

“I think you have to remember what it's like to be an artist. An artist goes into a studio and it's basically like running out into Grand Central Station without your clothes on.

"You know, you're standing there emotionally naked and putting everything on the line and how a producer responds to that is really critical. Either the artist is going to be comfortable and keep going or he's going to close up forever.

I would recommend practising benign honesty

"So, I would recommend practising benign honesty. You’ve got to tell the truth but you can be nice and compassionate about it and keep the positive energy flowing.”

4. Don't be arrogant

“Don’t be arrogant and don't take yourself too seriously. I picture this image, which is literal of course, but it's poetic.

"I picture this great creative ether way up there, you know, and the artists who are great have longer tentacles so they can reach to the farthest regions of that creative ether to pull out the deepest ideas. And, as the producer, you're not doing it. That's not you!

As the producer, you're not doing it. That's not you!

"You're just there to aid that thing. And it's easy to think that the ideas are coming from you. It's easy to pick up the arrogance.

"People treat you with a lot of deference if you have a hit record as a producer and you need to be confident and positive about your ability to help get good results, but don't make the mistake of thinking that you are the source of the creative energy.”

5. Have fun

“People can hear the struggle coming through the speakers and they can hear over-thinking coming through the speakers and they really don't like it! They can hear if it's loose and fun and for real.

"I’ll tell a story. I was producing an Iggy Pop record called Brick by Brick [1990] and we were cutting a John Hiatt song, Something Wild, and John happened to be working in the studio next door, which was just a coincidence. So, we invited him to come in and he came in, but at the end of the day at about 8 o'clock and Iggy was exhausted.

You can change the outcome by being positive. All producers should do that

"We were eating dinner and we didn't make him stay and Iggy kind of felt that maybe he had insulted John by not making more of an effort to put dinner down, which wasn't true. [Iggy] was just sensitive and he felt really badly about having possibly insulted John Hiatt.

"So, when it came time to cut the song, he was kind of bummed out and he started it lethargically. Now, Kenny Aronoff was the drummer… and Kenny wasn't going to let that happen. He put a big smile on his face and he just played with such positive intensity that it turned the energy of the room around in about 20 seconds.

"It was just the sheer force of positivity feeding from this guy. He changed the molecular structure of the room, I believe. And it turned out so well, all we had to do was go back and punch the first 20 seconds of the song. Man, I'll never forget that. You can change the outcome by being positive. All producers should do that.”