Cut Copy

Cut Copy

Melbourne-based DJ Dan Whitford established Cut Copy in 2001. He was inspired by sample-based artists such as the KLF and DJ Shadow, who - in his own words - made the process of making music seem accessible to non-musicians.

From these sample-based origins, Cut Copy grew increasingly towards a live band format, and in the last decade have revolved primarily around the line-up of Whitford (vocals, keyboards, guitar), Tim Hoey (guitar) and Ben Browning (bass).

Over the span of four albums, the 'dance-rock' band have developed a sound that delves into dreamy, hypnotic cascades and reverberant arrangements.

The group's new LP, Free Your Mind, was initially produced during sessions in Melbourne, before the quartet relocated to the upstate New York studio of Dave Fridmann (Tame Impala, The Flaming Lips, Mercury Rev) for mixing.

The follow-up to 2011's Grammy-nominated Zonoscope, Free Your Mind marries real-time stimulus and meticulous sequencing informed by a Summer of Love DJ's record box and the shared rapture of youth revolutions (past, present and future).

In between rehearsals for their upcoming world tour, Whitford caught up with MusicRadar to discuss the "uplifting, psychedelic vibe" of Cut Copy's latest LP.

When establishing an album's creative direction, do you tend to look back at your own catalogue or more at what's happening around you in music?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I think it's a combination really. We never want to repeat ourselves, so we're always looking for a new direction or set of boundaries for each record. This is as much for our own sanity as it is for an outside listener, but I think it's always good to have some idea of what's happening around you, so we certainly took on some current reference points.

"That said, listening to Free Your Mind I hear hints of everything from ELO and OMD to the Orb and Primal Scream, among others."

Was 'Madchester' and the Andrew Weatherall productions an intentional touchstone for the new album, then?

"Yeah, definitely. I guess we developed a taste for Weatherall's productions while making Zonoscope, so they were fairly present in our minds while making this album. He was obviously a major player in the early '90s UK dance and indie scene. I guess I'd become fairly obsessed with some of the acid-house tracks in my old vinyl collection, so it was really a process of rediscovering some records that I hadn't played for about ten years."

Did you consciously lay out a production or conceptual roadmap prior to recording?

"No - I really just try to find some records that feel fresh and interesting to listen to. That's usually the starting point: assembling some influences, or a collection of favourites, and then trying to shape them into something new.

"Having reconnected with a lot of early UK dance stuff, I bought a bunch of old digital synth gear; the kind of stuff that in recent times has been considered too cheap, harsh and digital to be desirable to synth collectors, but it was actually fairly integral to the sounds of that period.

"A lot of the old synths from that period had a really harsh, almost 'rude' quality to them. That had been a turnoff for a lot of people in recent years, but I started to think that 'rudeness' was actually kinda cool. As a synth purist, I've always felt it's important to experiment with real old instruments like that."

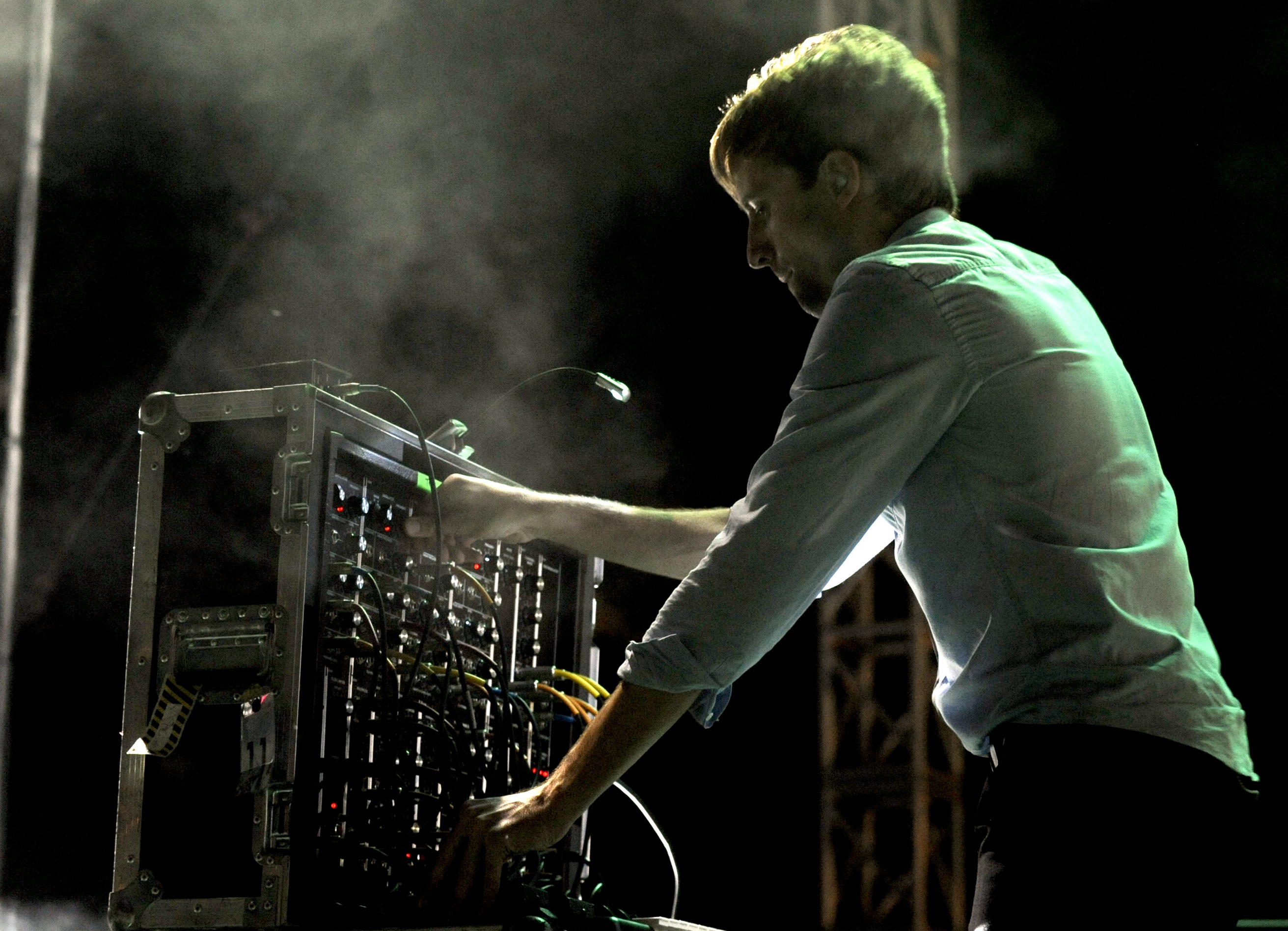

Image: © Kirsty Umback/Corbis

Do you prefer hardware synths over emulations, or will you utilise a combination of the two?

"I use both. I don't really have a mindset against plugins and VST instruments. Some actually sound pretty amazing. But I also have a big collection of analogue and digital synthesizers and vintage audio gear in my studio.

"I bought a bunch of old digital synth gear; the kind of stuff that in recent times has been considered too cheap, harsh and digital to be desirable to synth collectors."

"I think sometimes having a 'real' interface and being able to manipulate it in a hands-on way can change the way you use an instrument, even if it sounds quite close to its plugin counterpart. I think, also, being forced to perform gives you a different result to being able to endlessly tweak and perfect something using MIDI."

In terms of percussion, what are the challenges when combining live and synthetic sounds, and how do you dial them in together?

"I guess there's a range of challenges with that. Thankfully, Mitchell is a great drummer, so keeping to a programmed rhythm is something he's always just been able to do. Generally it's just a matter of finding a balance between the two.

"Obviously some things need to feel more 'live' or more 'programmed', so you'd adjust levels accordingly. Having competing low end, like multiple kicks, can be problematic, but often you can cheat that by slightly moving them around in [Propellerhead] ReCycle or [Pro Tools] Beat Detective. Where there's a will there's a way."

What's the core of your production setup?

"I use a basic setup: Cubase as the DAW; an iMac with Focal speakers; and the Universal Audio 2-610 [all-tube, dual-channel] preamp for vocals and other acoustic instruments.

"Then there's the room full of synths... but, having said that, I try to keep the setup as simple as I can for each song. Having a simple, streamlined approach when doing basic writing, using a small number of things to their fullest, seems the best way to get an interesting result.

"I run all my vocals, bass and other assorted things through my UA 2-610. As far as microphones go, I used a basic handheld condenser. I've used vintage mics when doing proper studio recording, but found them to be a little less versatile when recording other things.

"Plus, I'm not really a perfectionist on this side of things. I'd rather just get ideas down quickly to keep things flowing."

Image: © Tim Mosenfelder/TJM/Corbis

How you do approach vocals and lyrics: as a linear feature instrument, as a melodic outline to affect, or as a combination of the two?

"Obviously vocals are a focal point, so you have to treat them a little bit as a feature instrument. But having said that, when I'm sketching an idea out I sometimes will quickly lay down a melody - which is intended for a different instrument - as a vocal, and intend to replace it later. And it's funny how many times we've done this, but actually ended up leaving it in the final track. Sometimes these sketches just sound cool."

I've read that using a large warehouse space was a factor in Zonoscope's sense of headspace and tonality. Was there a physical equivalent that informed Free Your Mind?

"We recorded a lot of the live instruments in a converted church, so we had a great sounding space to play with. In fact, it was probably a lot better sounding than the one used for Zonoscope, not to mention having carpet and heating!"

Working with both room responses and virtual environments, how has your relationship with layering and stereo changed over time? And what are some of your favoured techniques for automating movement within a track?

"I think I've gone from our second record [2008's In Ghost Colour] being fairly conservative with stereo, where we worked at the DFA Studio and recorded everything mono, to this record where there is a huge amount of panning and auto-pans throughout.

"Having a simple, streamlined approach when doing basic writing, using a small number of things to their fullest, seems the best way to get an interesting result."

"I think this is partly down to Dave Fridmann, who mixed the record. He really tried to make everything have some sort of ear-catching sparkle, whether it was via panning or through a harmoniser or some other way."

What specifically did you hope Fridmann would contribute to the sonic architecture?

"I guess we were really looking for something unexpected from working with Dave. He's been involved in so many iconic records that have been commercially compatible, but also really interesting and experimental, so we thought he'd be a great choice.

"His approach is quite different to how I might personally approach mixing and assembling our music, so it was interesting to have him provide his own take on the tracks. He uses a lot of distortion on everything, as well as an array of tape delays and harmonisers.

"Initially some of the mixes really threw us, sounding so different, but by the end we were loving his perspective. It really felt like the record became something unique from his involvement."

When mixing and mastering tracks for Free Your Mind, was there a specific listening environment or approach you were keeping in mind?

"We didn't want to limit the target space and audience to one thing, so we really kept it quite open. We wanted it to be possible to listen to our record on headphones in a bedroom, or out at a big club or even on a festival PA.

"Our music isn't just about one of those scenarios, so we wanted it to be compatible with any of them. And, thankfully, I've always had the opinion that good mixing and mastering should work for all of these."

What got most tweaked in the transition from pre to post-production of Free Your Mind?

"There was a huge amount of restructuring that happened between the demo stage and the final stage of this record. It's something we've never really messed with too much in the past, but we spent a good two or three months just restructuring and then re-recording parts to suit. It definitely feels like we left no stone unturned on this record."

In retrospect, what do you feel this album has freed Cut Copy to explore?

"It's always impossible to tell after you've just finished a record. I always want to do the complete opposite of what we've just finished whenever I think about that. But over time we always seem to converge back with the ideas we'd be exploring making that record.

"I think there's a soulfulness to some of this record that might be revisited at some point. I guess we'll have to see if that actually plays out."

Cut Copy's fourth album is out now on Modular Recordings.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track