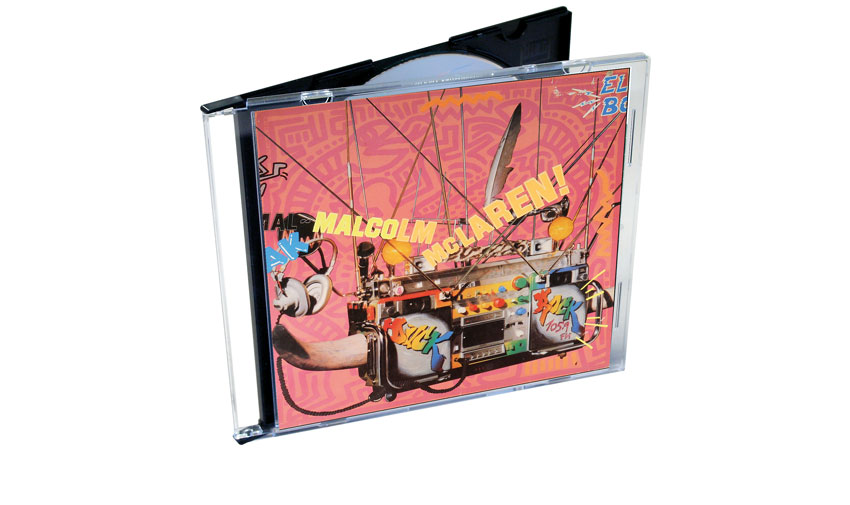

Classic album: Malcolm McLaren's Duck Rock

Malcolm McLaren invents World Music

Before M.I.A., Heinz beans, and Paul Simon, there was Malcolm McLaren. The Pop impresario, ex-Sex Pistols manager, media manipulator and cultural buccaneer, would have likely considered himself the first to use indigenous rhythms for modern Western gain.

"Malcolm formed a plan to travel to the far reaches of the globe to record the untapped wells of ethnic music that had been bubbling away there for generations"

After the whirlwind of punk, and some daring new wave, he 22 was looking for another scene to plunder, invent, exploit and remix, and plumped on earth's. Along with super-producer Trevor Horn he formed a plan to travel to the far reaches of the globe to record the untapped wells of ethnic music that had been bubbling away there for generations.

Joining them would be Horn's head engineer, Gary Langan, whose job it was to try and capture these strange new artists however he could, to take back to London and turn into a Pop record.

"All Malcolm knew was that he wanted to make an eclectic album, but he had no idea how that would be done," says Langan. "That was his idea and it stopped there - then it was over to Trevor to make it work."

For no real reason the three of them headed to New York to get the ball rolling. For a week Langan and Horn sat in separate hotel rooms, doing absolutely nothing. Nobody knew how to get this thing started.

Luckily McLaren had been doing what he does best and sniffed out the freshest sub-culture in town. Way after midnight a local transsexual club opened its doors to the Hip-Hop kids from The Bronx, and he was there to discover the graffiti, Double Dutch skipping, rapping, breaking, and scratching, that would eventually feature on the Duck Rock album.

Malcolm McLaren in New York in 1978 © Bettmann/CORBIS

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"He took me to this club and it was one of the most enlightening things I'd ever seen," says Langan. "It had a whole culture of entertainment there with all these different people reacting to the music. It was a pivotal moment in my life - these kids showed me that we really could do anything we wanted."

As the project gathered steam, further enlightening encounters took place in apartheid-era South Africa and the American Deep South. Tribal rhythms and banjo-pickin' added what Langan calls "extra ammunition" to the scattergun drum machine beats and cutting edge sample splicing they made.

"I had loops of the Mariachi bands we'd recorded, girls skipping, South African lyrics, and bits from the Hillbillies, and we just fooled around with them," says Langan. "Then, slowly but surely, we started to have multi-tracks that could resemble an album."

It would be a truly groundbreaking album, years ahead of its time. The fusion of world rhythms, Bronx slogans, DJ edits and goofy squaredancing was unlike anything else that would trouble the Pop charts for many years. Duck Rock might have been programmed like a World Music radio show, held together by your guides, The World's Famous Supreme Team, but it was the sadly departed Malcolm McLaren who was grinning as he turned the dial.

"I would say that working on this album with Malcolm showed me that if you really wanted to do something you could do it," says Langan. "He started off with this bonkers idea and we made an album. He used to call me 'boy'. He never called me Gary until the very end. He'd done the Sex Pistols, so I could take it [laughs]. He was sensational to work with. I learned so much."

After Duck Rock Gary Langan would co-found the seminal ZTT Records with Trevor Horn and released major works by Art of Noise and Frankie Goes To Hollywood. McLaren recorded a Top 20 adaptation of Madame Butterfly. Here Langan talks us through the album, track-by-track...

Obatala

"Duck Rock came out in '83, but it was started a lot earlier than that [laughs]. It was just one of those albums that happens in your music career that is completely different from everything else you will ever do.

"I can remember 95% of that album, as opposed to other albums I've worked on - they're not bland, but they aren't full of the things that happened with Duck Rock.

"From the minute it started, and the very first meeting I had with Malcolm McLaren, I knew it would be different. Trevor uses the phrase 'It's like knitting fog' to describe making Malcolm's albums. You'll see why!"

Buffalo Gals

"We recorded that in Tennessee. This track comes from the bones of our recording there. The whole thing of doing a 'call', as it's known, is a classic Hillbilly lyric. That's Malcolm going 'Buffalo gals go round the outside'. We couldn't use much of the actual Hillbilly's recording because it was all over the place [laughs]. That's how it was born, with Malcolm learning that style from them and doing it as a sort of Rap.

"Underneath we made this mad backing track back in London because Trevor had got the LinnDrum. Anything new that came out he had to get. If it was on the market we instantly had it - the Fairlight, the LinnDrum. We had so much great new kit."

Double Dutch

"The rhythm track was recorded in South Africa, then we wanted to mix that with the idea of these skippers, or Double Dutch jump-ropers, from The Bronx.

"I recorded them skipping in New York. We went to the Power Station, which was getting famous as Bowie had just recorded Let's Dance there. I did a reccy of the place and said I'm working with Trevor Horn and Malcolm McLaren, and they had no idea who we were, but I get these skippers in and spend the afternoon setting up mics around these girls.

"I just put the armour shield up and got on with it. I needed the sound of girls skipping, so that's what I got. I didn't care if they were laughing at me."

Merengue

"This was done in New York with a Mariachi band. [Laughs] God, this is sparking some memories! I remember going over to New York and taking the subway to Queens. We ended up in this deepest, darkest spot. Again, I'm dumped into this funky little studio. As soon as I came out the subway to see the place I was like, 'Wow! It's just like Blade Runner!' I just set up and tried to record this Mariachi band, which ended up as this track.

"It's just them in the studio, with maybe some keyboard overdubs by Anne Dudley, later. I think Thomas Dolby played some keyboards on the album too. Usual Trevor thing, he would have said, 'Why don't you have a go?' I can't be sure on which tracks though."

Punk It Up

"This was done in South Africa, and features a guy called 'Big Voice' Jack [mimics deep voice and bursts out laughing]. He's from Soweto and only had one tooth in his mouth! He was about 60, but he had the wackiest voice ever.

"All the time while we're in South Africa things are going through Malcolm's head, and he's writing funny lyrics down. He'd done the whole thing with the Sex Pistols, so he wanted to Punk It Up and pinch stuff, lyrically, from what he'd done before.

"He went into the booth to sing something - I couldn't keep a straight face. I was belly up! Trevor got so angry with me he chucked me out the control room. I was in tears."

Legba

"That was done when we were in New York. I think it was a take on some ethnic Mexican-based music. We did it with the Mariachi band that Malcolm had found - it was a bit of a collaboration, really. "This track is a big PPG Wave number. You can really hear that synth on here. The vibe sound on this? That's all PPG Wave, and that's all Anne back in London. The drum track and everything else is all from sessions in New York.

"Anne was great. You can just hear her fabulous chords all over the album. She is just a fabulous musician, and a very talented pianist."

Jive My Baby

"This was another one from the crazy times in South Africa. Malcolm had the idea of going to Johannesburg to capture the tunes they had there. All I used to take with me to record was a pair of speakers. That's all I used to travel with. I'm fairly good at what I do, so I can tip up at most places and if there is some sort of recording facility I can get it to work.

"This features 'Big Voice' Jack. If you listen to a lot of the stuff we did as the Art of Noise that came later he kinda features in there too [laughs]. He was in left in the Fairlight CMI. There were no rules about sampling then. You could get away with blue murder, which we did [laughs]."

Song For Chango

"This features percussion from Luís Jardim, and quite a lot of Anne on here too. Luís was part of the team when there was any percussion to be done. You'd phone him up and ask him to come in and he'd always be a day late, bless him.

"This started life in New York, and then work continued back in London. When we finally got back to London to work on all this material we'd assembled from New York, South Africa and the Deep South, we got down to the core production team. Which was basically what would become the Art of Noise - me, J. J. Jeczalik, Anne Dudley, and Trevor Horn. We'd just finished producing ABC's The Lexicon of Love album, so were in good form."

Soweto

"Was this album people's first introduction to World Music? I'm sorry, it beat Paul Simon's Graceland hands down... hands and fists, as far as I'm concerned. Duck Rock was World Music. But what Paul Simon did, and what with the size of him, he got the accolades of doing the first World Music album. I don't feel bitter. I know what we truly went through with this album with Malcolm.

"And Malcolm did pay these people. There is a sort of a rumour going around that Paul did not properly pay the musicians he used, and it put a bad taste in everybody's mouth. Especially in Johannesburg - they felt they got ripped off over it. Malcolm paid them so much that one of them could now afford to go off to a fancy hotel and get married!"

World's Famous

"This was written in London when the two DJs, Sedivine the Mastermind and Just Allah the Superstar, from The World's Famous Supreme Team were over to try and re-record the radio show stuff I'd heard them do in New York.

"It was my job to say, 'Look, I know you've never done anything like this before, but trust me, it'll work'. They would look at me like I was nuts. 'You can look at me like I'm nuts, but this is what we're gonna do, pal'. It didn't matter if it was in some studio in Queens, or Johannesburg, or in Knoxville with some Hillbillies, I had to play this act and be bullish about things."

Duck For The Oyster

"Malcolm wanted to record Hillbilly music. We were like... fine [laughs]. We turn up at this place in Knoxville, Tennessee, and find a spot called the Tri-State Recording Studio. It was this little place with a cutting room out the back. You could go in and walk out with an album.

"Malcolm went off to the mountains and found a Hillbilly family that could play. They all came down on this open back truck from the Hills. The whole family - uncles, cousins, the lot. They had tub bass, Jew's harp... it was the whole nine yards. The grandma only had four teeth in her mouth, and they all looked the same.

"When Malcolm came to pay them he only had hundred dollar bills. They'd never seen a hundred dollar bill. They wanted proper money! He only had a thick wallet of hundreds. They must have had trouble spending that there."