Are music production values still improving?

Today's mixes may sound different to older ones, but are they actually any better?

While it's debatable whether or not the songwriting, performing and arranging skills of the average musician have consistently improved over the years - in fact, some would categorically argue that they've got worse - it's widely assumed that music production standards have improved.

Even played through the cheapest speakers or headphones, mixes from ten, 20 and 30 years ago have a very different sound to those that are being created today, and - on a technical level at least - you'll often hear it said that songs that are released now sound "better" than those from the past. Indeed, in most cases, they certainly sound more polished.

However, although there are rules that can be applied to it and techniques that can be learnt music production is not an exact science. One person's understanding and opinion of what sounds 'good' might be completely different to someone else's, and it's tempting to ascribe quality to something simply because it sounds familiar and 'of its time'.

It's worth asking, then, if music production values really have improved. And, if they have, how much better can they get before some sort of quality ceiling might be reached?

Past masters

Tim Oliver is a producer/engineer who's twiddled the knobs on countless records. What does he think it is, specifically, about older mixes that can make them sound dated? "The immediate impression is often down to fashion," he says. "Mixes from the '80s and early '90s are often really bright with clicky bass drums and ridiculous snares. I blame it on the SSL desk EQ and compression [that was popular at the time]."

"Also," Tim continues, "from then, and particularly before that period, records often sound unfinished to me because there are so many things that you could do now to improve them technically."

Producer/engineer Jon Musgrave also believes that changes in technology have had an impact on how our mixes sound: "Mixes from ten years ago generally sound less upfront," he tells us. "Go back 20 years and it's even more marked. In part, this is down to analogue desks, and tape in particular rounding off the edges, but it's also related to the lack of maximising limiters, particularly 20 years ago."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Learnt imperfections are what give character to a song. It's hard to resist the temptation to clean up and round off the edges because you can." Tim Oliver, producer/engineer

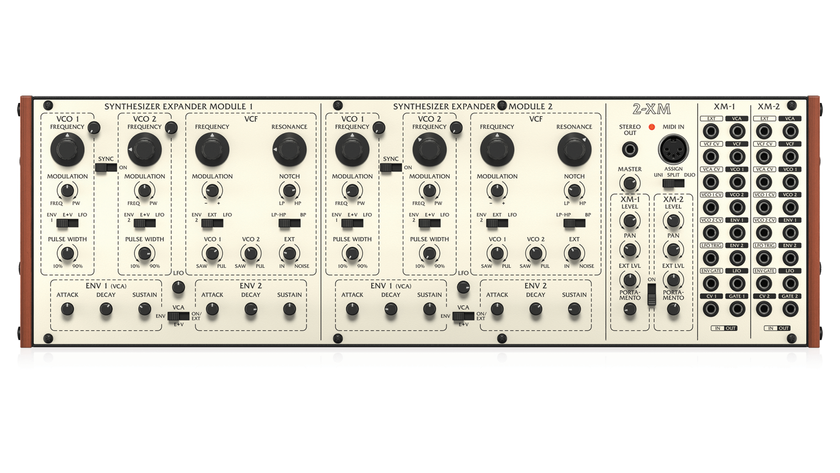

Fair enough, but the irony here is that a huge number of today's music producers think of that 'analogue sound' as the sonic equivalent of the Holy Grail, seeking out vintage outboard, console and tape emulation plugins that will help them add that elusive warmth to their (presumably) cold and clinical digital productions.

What's more, limiters are often cited as the defining weapons of the loudness war, in which producers attempt to create ever- louder mixes at the expense of dynamic range. So, is it really true to say that today's mixes are technically better than those from the past?

"Yes and no," says Tim Oliver. "I suppose, on a technical level, yes, but that doesn't mean they're aesthetically better. Learnt imperfections are what give character to a song. It's hard to resist the temptation to clean up and round off the edges because you can. A better mix is often one with incorrect balances, things jumping out at you, and so on. When everything is perfectly in balance and inoffensive, the result can be boring and lifeless."

Celebrating sameness

Another accusation frequently levelled by many - not least your dad - is that all new music sounds the same, but Tim Oliver feels that you can't just blame technology for that. "There's a homogeneity to records now that's often blamed on 'digital', but is really down to tidy mixing and over-mixing. Listen to Iggy and the Stooges - no-one would mix a tambourine that loud now!" he laughs.

That said, with more tools at our disposal, it's certainly tempting to 'do more' with a mix these days. Discussing the recording of the Oasis album Be Here Now, Noel Gallagher spoke memorably about trying to use all the channels on the desk, and he's certainly not the only one to apply the 'throw everything and the kitchen sink at it' philosophy to music production.

"Older mixes often - though not always - focus on fewer elements," explains Jon Musgrave. "There are obviously plenty of exceptions, but the trend now is definitely to fill up space with more elements. Unsurprising when you have unlimited track counts, but it's also down to having more precise editing, processing and mixing tools available."

A matter of perspective

The next obvious question, then, is where we go from here? Based on what's happened in the past, it seems inconceivable that records produced in a decade's time won't sound different to those that we're listening to today, but will the standards of their production actually be any higher?

"They will certainly change, and in that moment they will be seen as an improvement," reckons Tim Oliver. "In hindsight, though, probably not. In the '80s, everyone thought that the Trevor Horn-led sonic revolution was an improvement, remember."

"Technology has provided immense flexibility, and this remains the driver," adds Jon Musgrave. "It's already allowing us to mimic sonics from the past, and this could easily lead to a very retrospective era."

In other words, it's likely that the contradiction in music production - the one that sees software and hardware manufacturers trying to sell us gear that will improve the quality of our tracks while simultaneously marketing products that are designed to ape the sounds of the past - will continue. Whether or not we'll be able to hear any tangible improvement is largely academic: as long as people think that there are better tools out there, they'll continue to buy and use them.

"The human ear is easily fooled, and it seems that end user convenience is now valued over audio fidelity." Jon Musgrave, producer/engineer

"I already think that the sample rates of 96 and 192kHz are way beyond the level where most humans can tell the difference," concludes Tim Oliver. "[Technology] will always keep improving because of the capitalist conundrum - we're enticed to buy the new gear in that belief [that it will improve our music]."

But what of the people actually listening to this music? As we alluded to earlier on, increasingly, music is being played through headphones and small wireless speaker systems, and almost always from a compressed format like MP3. This being the case, are the public really demanding 'better' sound?

"The human ear is easily fooled, and it seems that end user convenience is now valued over audio fidelity," says Jon Musgrave. "I'm not sure the drivers are there to forge better quality standards, although they may forge different quality standards."

So, it seems likely that the future arguments about the values of music production will be had by producers rather than consumers, which is probably the way it's always been. People might know that their music sounds different and perceive it to be an improvement on what they've heard before, but who's to say whether it actually is or not?

This article originally appeared in issue 202 of Computer Music magazine.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

“My love letter to a vanished era that shaped not just my career but my identity”: Mark Ronson’s new memoir lifts the lid on his DJing career in '90s New York

“I'm always starting up sessions and not finishing them, but I don't see that as unproductive”: Virtuosic UK producer Djrum talks creativity and making Frekm Pt.2

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)