20 hardware samplers that changed music production forever

From the Fairlight to the Octatrack, the machines that opened, blew and melted our minds

Sampling tech titans

Today's samplers offer few surprises and elicit only occasional excitement or ire. Musicians and producers know what to expect. After all, samplers have been around for decades, and feature sets have over that time slowly evolved towards a fairly generic tool kit. Multisampling, key-mapping, timestretching, tempo-matching - all obligatory functions of any modern sampler.

This wasn't always the case. Once samplers were rare, costly and without precedent. There were no rules about what a sampler should include - heck, one of the first models didn't even offer envelope generators! Should a sampler be tied to a keyboard? A beatbox? Or should it be a clinical rack-mounted production tool, the obvious offshoot of the digital delay?

Nobody knew. It took numerous courageous designers and years of hands-on experience by the customers before the sampler reached its current state of refinement.

Some instruments came and went without making much of a dent. Some were notoriously complex and confusing - a study in how not to design an interface. A few were so well thought out that they became the templates for designs still in use thirty years on. A very select few still would inspire entire generations of tech-savvy musicians and producers,

We're here to celebrate the early innovators and risk-takers and the groundbreaking, game-changing samplers they created - instruments that shape the way we make music even to this day. So settle in and take a trip through hardware history.

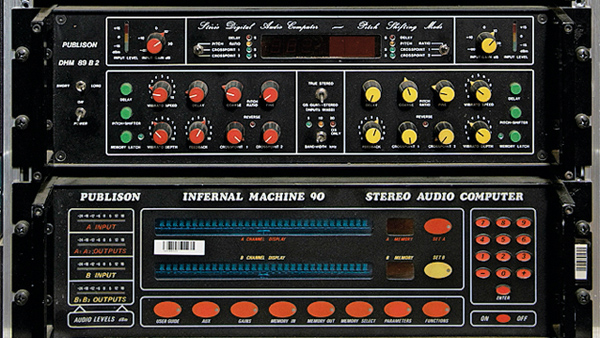

1. Publison DHM 89 B2

Many a musician has gotten their first taste of sampling using the freeze function on a digital delay unit, and Publison's DHM 89 B2 is the grandaddy of all sampling delays.

A thoroughly high-end processor, it found favour with a number of big names. Popular with electronic artists such as Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, the DHM 89 B2 also found its way onto many a pop production - Cyndi Lauper's She's So Unusual being but one example.

Publison was not blind to the growing fascination with keyboard samplers, eventually releasing the KB 2000, a rather spiffy three-octave keyboard with which the DHM 89 B2's samples could be played chromatically. Like the machine it was designed to accompany, the KB 2000 is a looker, with a particularly eye-catching memory position display that would look right at home on the bridge of the Galactica.

Publison's fantastic follow up, the Infernal Machine 90, gets most of the love from gearheads, but the DHM 89 B2 got there first.

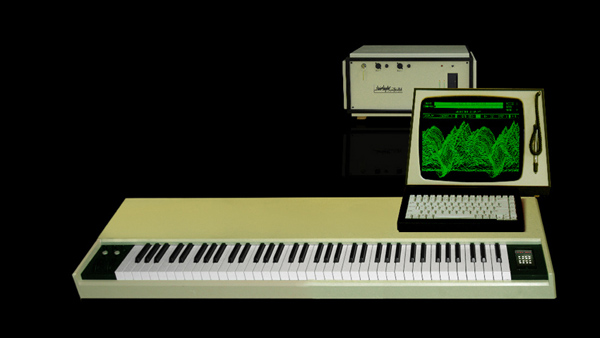

2. Fairlight CMI

If one were to suggest that the Fairlight CMI was the most important sampler ever made, there would be very few naysayers. The significance of the Fairlight rests not simply on the fact that it was the first polyphonic sampler to be released, but also by dint of the fact that its dizzying price ($25,000+) restricted ownership to the sorts of producers and artists who produced the biggest chart hits. For this reason, the sound of the Fairlight is forever bound up with the 1980s.

An eleventh-hour addition to the Fairlight's digital synthesis, sampling turned out to be the instrument's breakthrough and breakout technology, and one that would kickstart the music industry into entirely new directions.

The first generation of Fairlights could manage 8-bit sampling and eight notes of polyphony. It would be 1985 before the Fairlight sported CD-quality 16-bit/44kHz sampling. Nevertheless, with its sleek white cabinetry, computer terminal and attached light pen, the CMI looked like it had been beamed in from the future.

Ironically, this once-futuristic instrument is now the subject of retro lust. The expensive, high-end sound of 1979 is today loved for its lo-fi character. Imagine that!

3. New England Digital Synclavier II

In the beginning, there was the plain ol' Synclavier. A computer-based FM synthesizer, a small number of Synclaviers made their way into universities and the hands of a few musicians - Frank Zappa among them.

By 1980, the system had been given a complete overhaul, resulting in the Synclavier II, which itself would be tweaked and honed, eventually adding 16-bit sampling courtesy of New England Digital's Sample-to-Disk option - the world's first commercially available hard disk recorder.

Continuously evolving and advancing, by the time the third generation of Synclavier came along in 1984, it sported a new keyboard and a whopping 128 voices of polyphony. Along the way, the company had added a graphics terminal, additive resynthesis and even notation.

The starting price for a system was a breathtaking £40,000. Yes starting price. Needless to say, private owners were few and far between, but notable users included Sting, Geoff Downes, Greg Hawkes and Alan Silvestri.

By the 1990s, low-priced digital synths and samplers had all but edged the Synclavier out of the market. However, luck continues to shine on the fortunate few who still own these lofty dream machines, as aftermarket support has persisted even to this day.

4. E-MU Emulator

E-MU was in trouble. As the '70s came to a close, this purveyor of massive modular synthesizers and digital keyboards had just lost its cash cow. Sequential Circuits had ended its royalty payments on the E-MU-designed keyboard used in its blockbuster Prophet-5 synth. Forced to come up with a new product and inspired by the sampling functions of the Fairlight CMI, E-MU's founders Dave Rossum and Scott Wedge decided that it was time to release a sampler of their own.

That sampler was the Emulator (nobody had yet thought of calling a sampler a “sampler”). This hulking blue and charcoal behemoth debuted at the 1981 NAMM show, where it was embraced by Stevie Wonder who, in turn, would get serial number 001.

As a dedicated sampler was an entirely new idea, E-MU wasn't quite sure what the thing should do. To that end, the Emulator lacked a display, meaning sounds had to be looped by ear. It also lacked filters and, incredibly, an envelope generator. The 8-bit/21kHz samples played straight through every time a note was triggered.

Still, at $10,000, it was a damned sight cheaper(!) than a Fairlight and about two dozen Emulators were sold before the market dried up. A price-drop (to about $8k), a software update (with an envelope generator!) and, most importantly, a larger factory sound library got 'em moving again. The company would eventually shift around 500 Emulators before releasing the vastly improved Emulator II.

5. PPG Waveterm

With its unprecedented combination of digital wavetables and analogue filtering, 1981's PPG Wave 2 was a hi-tech dream synth with a price to match. PPG upped the ante with its follow-up - the Wave 2.2 - by introducing the optional Waveterm computer with which the user could create custom wavetables as well as record and playback short samples.

Connecting to the Wave 2.2 via a proprietary communication bus, the Waveterm was a massive blue box with a glowing green CRT display, chunky data entry buttons, and a pair of 8-inch floppy drives that were used to load and store wavetables, patches and samples (here called “transients”).

Limited by today's standards, the Waveterm allowed only minor editing of its grungy 8-bit samples. The coolest feature was its ability to resynthesize a sample for use in wavetables. The price for all of this hi-falutin' power? A whopping £3995 - in addition to £3995 for Wave 2.2 itself, without which the Waveterm was useless!

Eventually, the Wave 2.2 would give way to the more popular 12-bit 2.3 model and the 'Term would be upgraded to facilitate this advancement. Sadly, it lost that nifty resynthesis function along the way.

6. Kurzweil K250

With the release of Kurzweil's K250, the high-end sampler finally came into its own as a mature keyboard instrument. With their dedicated CRT displays and racks of hardware, previous samplers had seemed like industrial-grade computers with synth-style keyboards tacked on. The K250, however, was refined, classy, and built to play. Sporting a responsive 88-note piano-style keyboard and rakish good looks, this was a sampler for keyboardists.

The Kurzweil's sounds were not loaded in via computer disks, but were instead stored internally in ROM. PPG may have introduced the idea of synthesis based on wavetables, but its synths' internal waveforms were limited to single cycles, whereas the K250 offered complete multisamples of real instruments. It was - though the name was still decades away - the first ROMpler.

Though often described as a sampler, at first the K250 couldn't actually sample. This function was added later and - in an arrangement that wouldn't seem out of place today - required that the instrument be connected to a Mac.

All of this remarkable power could be had for just over £10,000 - a bit out of reach for those Holiday Inn gigs, then.

Those who could pony up the dough were, for a short time, able to do what no one else could: play fully realized, convincing strings, brass, woodwinds, and the now-legendary piano from a single keyboard instrument.

7. Ensoniq Mirage

To understand the impact of the Mirage, consider this simple fact: Ensoniq shifted around 30,000 of the things. That's approximately 8000 more units more than Akai would manage with the S1000.

Now consider the instrument itself: A nearly unadorned slab of metal with tiny plastic buttons, a single fader and an absurd two-digit hexadecimal LED display. There were pitch and mod wheels, a 3.5-inch disk drive, and a woeful five-octave keyboard.

Under this unassuming exterior? An equally unimpressive 8-bit sampling engine with sampling frequencies that topped out at 30kHz. The 128K memory could manage a pair of samples at any given time, with half the memory devoted to each. A simple 333-note sequencer was also included. Sound shaping came courtesy of a 24dB analogue filter, LFO and 2 x ADSR.

So why the massive sales? One word: Price. At $1695, the Mirage cost many times less than the nearest competitor, snatching the world of sampling out of the manicured hands of the moneyed few and putting it within reach of the gigging musician. Underground music would never be the same.

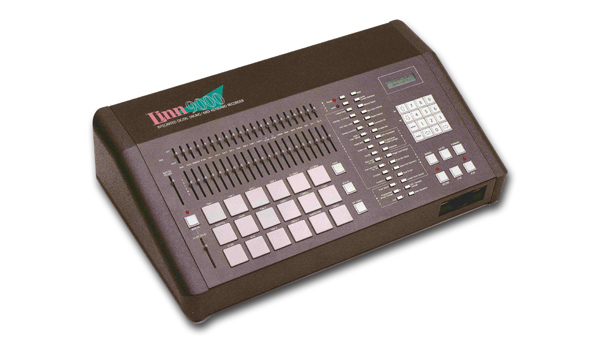

8. Linn 9000

At this early stage in the game, samplers had become inextricably tied to the traditional keyboard. It was assumed that musicians would want to sample existing instruments and play them melodically.

Even so, Roger Linn had already demonstrated the potential of using pre-fab samples as the basis for a drum machine with both the LM-1 and LinnDrum. With the Linn 9000, he expanded the idea into a full sampling and sequencing workstation - and invented the modern groovebox in the process.

The Linn 9000 is instantly recognizable as the predecessor to the Akai MPC series to which Linn would eventually turn his attentions. The 9000 was well-appointed, with 18 chunky drum pads, individual sliders for volume and pan position, a 32-track, 60,000 note pattern-based MIDI sequencer, lots of sync options, and 32 onboard drum sounds.

Sampling was limited to 8-bit/37kHz files and total sampling time came to a little over 30 seconds. Just enough, then, to knock out a reasonably full rhythm arrangement.

The 9000 was a revolutionary idea, sadly hobbled by a buggy operating system and, at $5000, a price aimed squarely at demanding professionals who were loathe to accept its operational shortcomings. Still, it was a start…

9. E-MU SP-12

Roger Linn wasn't alone in his belief that sampling and drum machines make for the perfect production pair. The clever heads over at E-MU had been thinking along the same lines (as they might. They'd come up with the Emulator after seeing a Fairlight in action at an AES show - where they'd also taken a keen interest in Linn's LM-1 drum machine).

Having had success with sample-playback in the form of the Drumulator, the company set about work on a sequel. This time around they included 12-bit user sampling in addition to the factory complement of 22 traditional percussion tones.

Today, the SP-12 is admired for its lo-fi sound, though at the time it was viewed rather differently. 12-bit sampling was a vast improvement over the 8-bit convertors on competing products, even if the sampling rate did top out at 27kHz.

The SP-12 had a relatively short shelf life, being replaced by the SP-1200 only two years later. The SP-1200 ditched the factory drum sounds, beefed up the sample RAM and became an instant classic among hip-hop producers. In contrast to the SP-12's brief reign, the successor remained on the market for an entire decade.

10. Casio SK-1

Those who couldn't afford an Emulator had to make do with a Mirage. Those who couldn't afford a Mirage made do with a Casio SK-1.

Designed and marketed as a novelty product, the SK-1 was in keeping with the rest of Casio's line of diminutive toy keyboards, with 32 miniature keys, built-in speaker and a handful each of PCM and synth sounds.

The SK-1, however, was capable of recording and playing back a single 8-bit/9.38kHz sample with a maximum length of just under one-and-a-half seconds. Samples were recorded via the built-in microphone or a line input around back and were stored in volatile memory. Once you turned the machine off, that sucker was gone. Only the most basic editing was offered in the form of 13 preset envelopes. Looped playback was also possible.

The SK-1 was the first sampler sold for under $100 and, even if marketed as a toy, was embraced by many a skint musician willing to settle for lo-fi industrial-style samples. These days, lo-fi is the thing, of course, and the SK-1 is embraced for its perceived qualities (or lack thereof). Even so, Casio sold a ton of the things, so secondhand units can still be found for a bargain price.

11. Roland S-50

With high-end options and a competitive price, Roland's entry into the 12-bit sampler arena was bursting with features if not storage, which - typical for the day - maxed out at 512KB. Luckily, samples could be saved via the built-in 3.5-inch floppy drive. Mind you, the sampling rate only extended to 30kHz, so not a lot of space was required.

All manner of editing could be performed on the samples. Auto-looping was included, as were digital filters and multistage envelope generators, though the instrument's minuscule, single-line vacuum fluorescent display meant that managing these parameters was not a lot of fun. Fortunately for S-50 power-users, the instrument came with its own alternative.

Indeed, the neatest thing about the S-50 (and its keyboard-less variant, the S-550) was that you could connect it to a CRT monitor, giving you a better view courtesy of the sampler's internal software. Likewise, the optional DT-100 Digitizer Tablet facilitated hand-drawn waveforms, manual finessing of loop points and more.

If not exactly a “poor man's Fairlight”, the £2300 S-50 nevertheless put some impressive features into the hands of working musicians.

12. Casio FZ-1

1987 was the year of the 12-bit sampler. The shops were stuffed with the things and musicians had no reason to expect better - at least until Casio dropped this bomb on the competition.

Prior to 1987, Casio's exploration of sampling technology was limited to novelty items like the SK-1 and SK-5 - cheap toys that were low on quality and big on fun. The FZ-1 was a different story altogether. A thoroughly professional machine, it offered 16-bit sampling (at 36kHz), an LCD big enough to display entire waveforms, built-in waveform generation, SCSI, and a five-octave velocity and aftertouch-sensitive keyboard. All for a price-busting £1799.

It did not go unnoticed by other manufacturers, one of them even going so far as to publicly (and wrongly) declare that the machine was not actually capable of 16-bit sampling.

Despite such ill intentions, the FZ-1 and its rack-mountable incarnation, the FZ-10M, sold in respectable numbers. Unhappily, there was a never a follow up, as Casio pulled the plug on its pro division not long thereafter.

13. Ensoniq EPS

Ensoniq's Mirage had at last put sampling into the hands of the average working musician. However, by 1988, competitors were releasing high quality 12-bit samplers with prices that were making the Mirage's 8-bit conversion and anaemic interface seem far too great a compromise. Ensoniq's response came in the form of the EPS.

The EPS (for Ensoniq Performance Sampler) offered 13-bit sampling, a 61-key velocity and polyphonic aftertouch-sensing keyboard, DS/DD floppy drive, optional SCSI and expandable 256 Kwords of RAM. Information was displayed through a 22-character vacuum fluorescent screen.

Up to 20 voices could be produced at any given time - just enough to create full arrangements using the EPS's excellent built-in 8-track pattern/song-based sequencer.

The instrument took its name from the fact that the EPS allowed the user to load samples while the instrument was being played - a feat as yet unrealized by competing products.

It was an excellent package and another bargain from Ensoniq, coming in at £1695. Mirage owners could load their samples into the EPS, making the upgrade path a little easier.

Unfortunately, the EPS was not the most reliable tool in the chest. The instrument was prone to bouts of instability, with spontaneous reboots a constant threat to those (such as your humble author) who dared to take one to a gig.

Nevertheless, it was a rousing success for the company. A follow-up, the EPS-16+ offered 16-bit sampling and built-in effects.

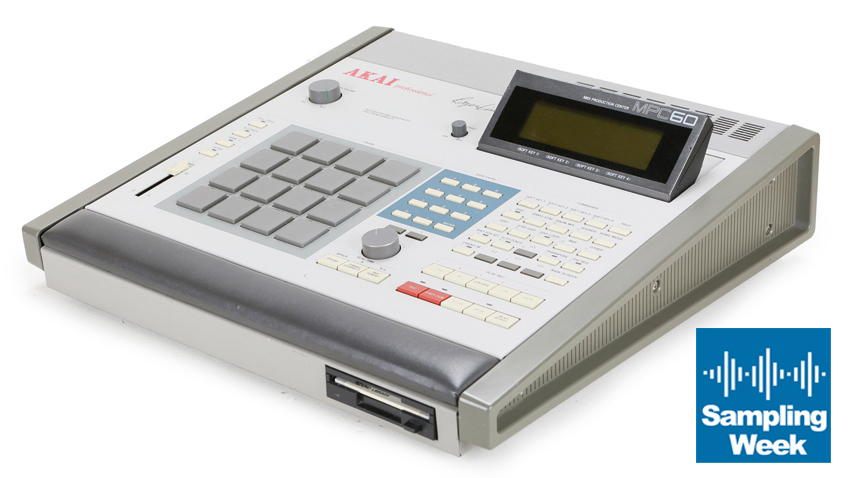

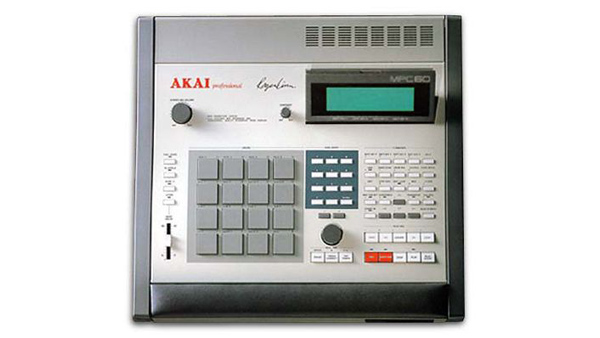

14. Akai MPC60

Rising from the ashes of the troubled Linn 9000, the MPC60 distills the best features of the 9000, refining and improving them to create would become a legendary workstation.

Akai had entered the world of sampling with its S612 three years prior to the release of the MPC60. In the interim, the company enlisted the aid of Roger Linn, fresh off of the dismantling of his own Linn Electronics.

Sampling technology had taken a significant leap forward since 1984, and the MPC60 was chocked full of cutting-edge features. It offered (among other things) 16 velocity-sensitive pads, 16-bit converters (with non-linear 12-bit storage), 13 seconds of sampling time, 16-voice polyphony, eight assignable outputs, optional SCSI interface, SMPTE support and 96ppq sequencing. A sizeable collection of high-quality drum sounds was included, spread across four floppy disks.

An instant success, the MPC60 became the de facto sampler for hip-hop and R&B producers, and still has pride of place in many modern production studios. Akai improved upon the design with a never-ending series of sequels, and there have been scores of imitations from other manufacturers.

15. Akai S1000

Akai's initial volley in the rack-mountable 'S' series, the S612, was something of an odd duck. Though its 12-bit converters were pretty darned good for its time (1985), users couldn't store samples without the optional disk drive - which used the quickly abandoned 2.8-inch quick disk format. Akai's follow ups, the S900 and S950, were steps in the right direction, with their serious-looking front panels, sophisticated editing, and 3.5-inch floppy drives.

As the decade neared its end, musicians and producers demanded professional standards. The popularity of the compact disc had raised expectations of sound quality. With better fidelity came the potential for closer scrutiny and 'CD quality' became a common marketing term. Akai's 1988 entry in the S-series would be the company's first CD quality sampler with its ability to perform 16-bit/44.1kHz stereo sampling. With 2MB of sample memory out of the box (expandable to 32MB), you could do quite a lot of it, too.

A wildly successful sampler, the S1000 would be rejigged and repackaged as the S1000HD (with a built-in 40MB hard drive) and the playback-only S1000PB. The latter was a canny move from a company who understood that many users didn't actually want to sample anything; they just wanted a means by which to play back a library of prefab sounds - a library Akai was only too happy to provide.

And it wasn't alone. With a staggering 22,000 units in the field, the S1000 became the file format of choice for sample providers, eventually becoming an obligatory standard that's still used today.

16. Ensoniq ASR-10

Having gotten its start with the low-budget, bare bones Mirage a mere eight years earlier, Ensoniq released what would be its finest sampler in 1992.

The ASR-10 was everything that the Mirage was not. Where the Mirage had been blocky, homely, and utilitarian, the ASR-10 looked as if it had been pulled from the Enterprise-D's Ten Forward lounge. In contrast to the Mirage's compromised specs, the ASR-10 was a thoroughly professional instrument, boasting 2MB RAM (expandable to 16MB), 16-bit/44.1kHz sampling, optional SCSI and even 2-track hard disk recording. 16-track sequencing was included and sound designers could enjoy the “Transwave” synthesis culled from the company's VFX line of synthesizers.

The ASR-10's built-in effects processing was its best feature. Internal and external sources could be routed through (and resampled with) any of 62 editable effects. The ASR-10's effects section would later be sold as a standalone device, the popular DP/4.

The ASR-10 was and is rightfully well regarded. A sturdy, solid and stylish performer.

17. Roland VP-9000

The music industry was changing fast at the turn of the Millennium. DAWs were coming of age, virtual instrument plugins were making a big splash and a company called Nemesys had only recently set the course for today's software samplers with its 64-voice disk-streaming GigaSampler software.

Yet one of the coolest samplers of the year was a 6-voice machine with a lousy 8MB of RAM.

The thing is, those six voices sounded like no other hardware sampler, thanks to Roland's latest development, dubbed VariPhrase. A familiar idea to the modern user, VariPhrase offered realtime independent manipulation of pitch, time and formants. You could use it to adjust the tempo of a loop without affecting its pitch and vice-versa. You could use it for creative vocal effects like gender-bending. Built-in effects included nine reverbs, chorus, flanging and dozens of multi-effects.

Clocking in at £2299, it wasn't cheap, and the associated V-Producer software only served as a reminder that desktop producers already had access to technology that could perform many of the same tasks. Nevertheless, it was a seminal instrument for the company, and the VariPhrase technology would be refined and reused to great effect in future products.

18. Akai Z4/Z8

If Akai's S1000 represented the pinnacle of CD quality sampling in its day, the Z4 and Z8 samplers represented - however briefly - what samplers could be in the era of 24-bit/96kHz recording.

Smartly appointed in silver and blue, with a sizeable display and friendly operating system, the Z4 and Z8 were functionally identical 2U rackmount samplers. The Z8 was the pricier of the two, having eight assignable parameter knobs as opposed the Z4's four. On the Z8, those knobs were affixed to a breakaway panel that also acted as a wired remote. Additionally, the Z4's optional (and excellent) effects card came standard on the Z8.

The Zs offered 64-voice polyphony, 16MB RAM (expandable to a respectable 512MB with 168-pin DIMMs), two independent sets of MIDI I/O (for 32 MIDI channels), and SCSI. All manner of optional I/O was available. A 20GB hard drive came installed as standard, facilitating the larger sample files that resulted from higher bit-depths and sample rates. A USB connector on the back allowed users to connect to a computer for editing or for shuttling samples about. A USB slot on the front was meant for sample storage.

It was - and remains - a thoroughly modern take on the hardware sampler. Sadly, it entered an industry that had no room for any such thing. Units were blown at at ridiculously low prices as Akai bid adieu to the rackmount sampler format that it had dominated for so many years.

19. Roland V-Synth

The VP-9000 had been a groundbreaking product, but it never sold in any significant numbers. Maybe it looked too much like a vocal effects processor to be perceived as a musical instrument.

Roland's next VariPhrase instrument would leave no room for confusion. The V-Synth combined time, pitch, and formant elasticity with virtual analogue synthesis and Roland's COSM effects modelling, putting it all under the control of a 320 x 240 LCD touchscreen.

The power of VariPhrase becomes readily apparent when using the V-Synth's Time Trip pad controller, with which you can 'scrub' sample time, playing through forward, backward or even freezing the sample. Playing it is great fun, possibly only matched by waving one's hand madly above the twin D-Beam controllers.

The V-Synth is not meant to be a sampler in any traditional sense. This isn't about piling dozens of multisamples on a key for realistic emulation of acoustic instruments. Just as the instrument's name drives home, the V-Synth is all about synthesis, albeit, synthesis derived from samples. A beautiful instrument inside and out, there is nothing else quite like it.

20. Elektron Octatrack

This clever tabletop sampler offers recording and playback of mono or stereo looped and one-shot samples, built-in effects, and Elektron's comprehensive grid-based sequencer.

Samples are assigned to any one of eight tracks and played back with what Elektron calls “Machines”, each of which is dedicated to specific set of functions. There are Flex Machines for slicing, time and tempo manipulation and even wavetable-style single-cycle play. Static Machines work for one-shots and Pickup machines are designed for realtime looping, ala Frippertronics. Neighbor Machines let you apply effects to an adjacent track (though each track has its own effects processor, as well).

Reaction to the Octatrack has been mixed, with some users taking issue with its learning curve, interface design and software quirks, while others have made it the centrepiece of their rigs.

A new version, the Octatrack MKII, has just been announced, and will be released in August.