Goldie & James Davidson: "I’m really not about presets, because if I’ve got them some other f*cker’s got them"

The duo behind Subjective invite us into their Thailand studio and talk up the latest album from their joint project

Goldie’s 30-year career has seen him pioneer the ’90s UK jungle, drum & bass and breakbeat scenes and work with a litany of high-profile musicians including Bowie, Noel Gallagher, 4hero and Pete Tong.

Despite numerous sojourns into acting and the art world, 2017 saw the iconic musician return to the musical fold with his album The Journey Man, working alongside ex-Ulterior Motive producer and revered sound engineer James Davidson.

Seeking to realise their potential as a production duo, Goldie then invited Davidson to begin writing and recording at his home studio based in Phuket, Thailand. The result was a new project, Subjective, debuting with the cerebral ambient album Act One – Music for Inanimate Objects (2019).

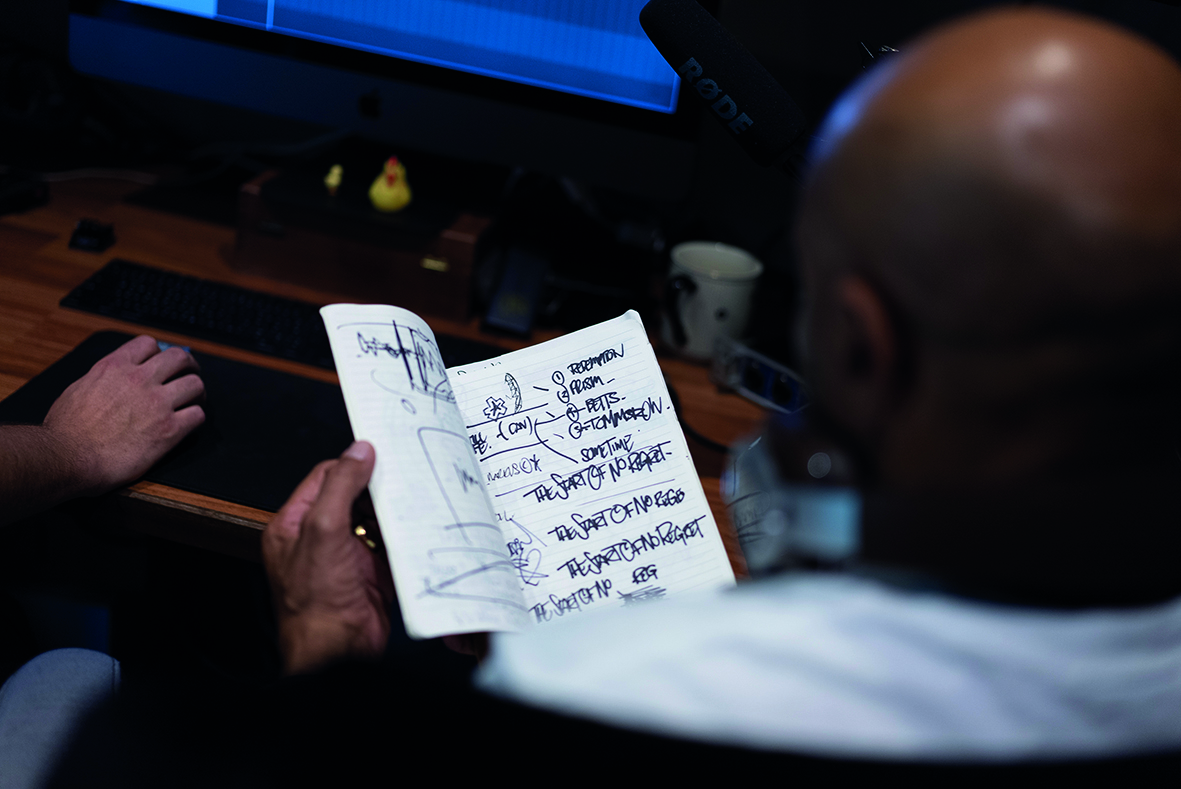

With tracks left over from those initial sessions, Pete Tong encouraged the duo to record a second long player, The Start of No Regret, which moves further towards Goldie’s drum&bass DNA.

You’ve been spending a lot of time together in Thailand. Is that solely about promotion?

James Davidson: “This time it was supposed to be solely about promotion and to show people where we wrote it and what we were doing, but as tends to happen when we’re in the studio, we ended up writing.

“We’ve actually been making a few really good Rufige Kru tracks, which was great because early tunes like Beachdrifta and Terminator were huge for me. That sound’s completely different to Subjective because we’ve been resampling old Metalheadz DAT pads from Timeless and leaning towards that DNA.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

How did you first get noticed by Goldie?

JD: “I first got noticed by TeeBee from Subtitles Records back in 2007. He put out our first Ulterior Motive single in 2009. Then I met Goldie at the SUNANDBASS festival in Sardinia and he told me to put the album out on Metalheadz, so we ended up releasing The Fourth Wall in 2014. He really liked the sound of the album and asked if I’d be interested in engineering his new record at the time, The Journey Man.”

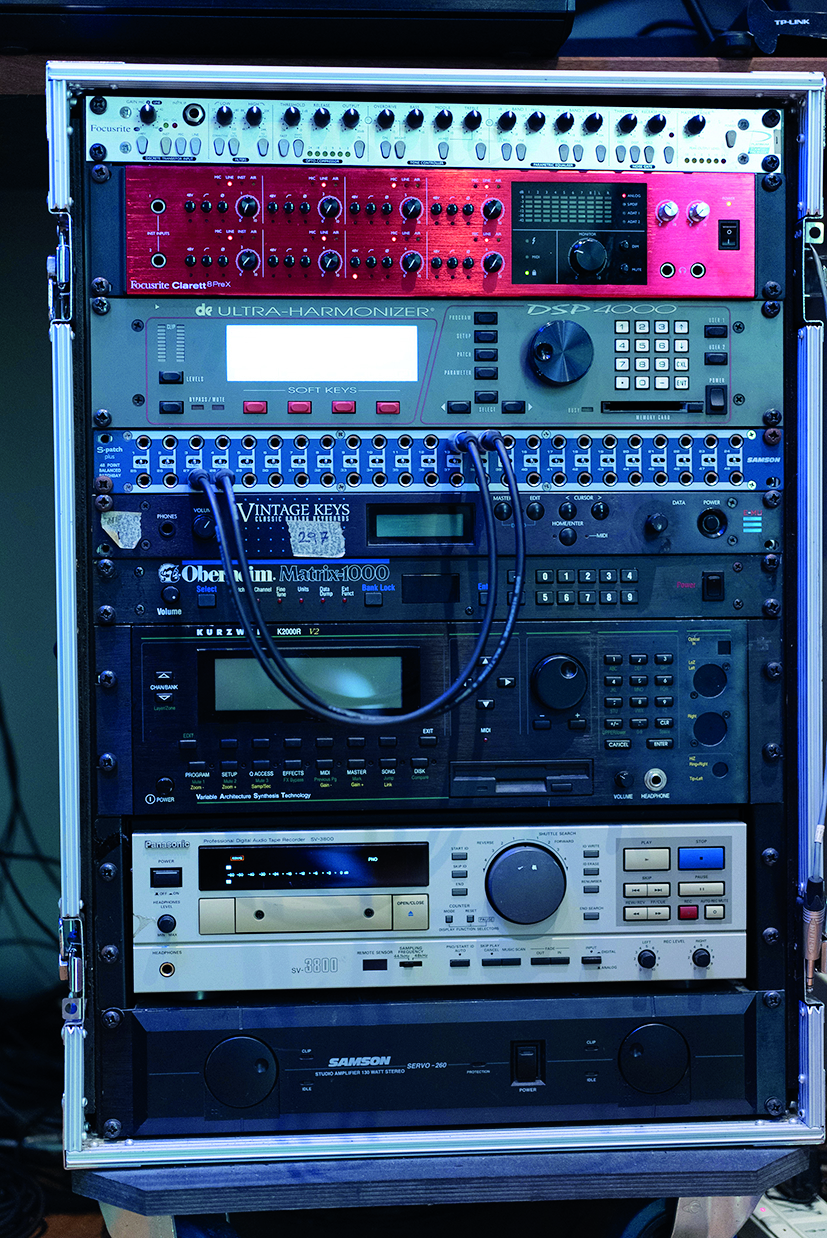

A lot of the warmth in the sound is down to James’ exterior hardware, which he builds himself

Goldie: “I liked the engineering but I also liked the fact that it wasn’t brittle. These days there tends to be no headroom on tracks and a lot of smashing, whereas I come from the DAT generation where there is headroom. James is in a digital bubble capturing analogue loops and when I dug a bit deeper and listened to tracks like Ulterior Motive’s The Elephant Tune I thought they were amazing. Knowing it wasn’t analogue, I felt there was warmth to his sound, a lot of which is down to James’ exterior hardware, which he builds himself.”

So you found in James an engineer who could take your sound to the next level?

Goldie: “I feel I’ve always had a role in taking engineers to the limit and had reached a glass roof with people like John Gosling and Mark Rutherford working out of William Orbit’s studio in Crouch End on Rufige Kru tracks like Krisp Biscuit. When you start doing classical music and zooming in at a score or an arrangement, as soon as you go back to electronic music and discard the ego you realise you’re just pushing buttons.

I had loads of recordings on DAT that were like bottles of wine fermenting on tape

“I had loads of recordings on DAT that were like bottles of wine fermenting on tape, so I got James to come to Thailand and throw himself into all of that stuff on The Journey Man. If you know drum&bass and programming then you’ll know that, compositionally, the track Prism is no joke and James really shone through on that because he has no glass roof. I wanted to stand back a little bit and share the fall with Subjective, which has been an amazing project to do that with. That’s why we’re here, but unfortunately he’s eating us out of biscuits at our home here in Thailand.”

The first Subjective album, Act One – Music for Inanimate Objects, was instrumental, cinematic and orchestral, so how did you want to approach this second album?

Goldie: “The whole idea of giving Music for Inanimate Objects an ambient vibe was ignored a little bit and the album didn’t register the way I thought it might. It’s a bit like opera, unless you’re really into it, no one wants to sit down and watch that for three hours because it’s a very niche thing.

Drum 'n' bass is the bastard child of electronic music

“So from my graffiti background I thought it would be good to create some really well-designed bubble letters that people could read musically and wouldn’t make you feel like you’ve had your brain pulled out your chest.”

What was Pete Tong’s involvement?

Goldie: “People forget that Pete Tong was the A&R man who signed Timeless. Then I went off and did Mother and didn’t give a fuck, so he almost felt robbed of that second album. When we were celebrating Timeless a couple of years ago, he asked what I was up to and I said I’ve got half an album sitting around but nobody understands what it is.

“We sent it to Pete, he flipped his lid and said can you get this done, so I told him to speak to the Sony bods and move it, which they did. Then Pete came with his smart A&R hat and said, “Can you put a couple of 155bpm things on there?”. So we did Dollis Hill Rufige, Sunlight and Reflection, which were a bit closer to home and fitted in lovely. It was a bit like, we’ve been doing kung fu for years, so all of a sudden we’ll do a bit of feng shui.”

Did you feel comfortable going back to the ’90s drum&bass vibe on certain tracks?

Goldie: “If you were standing in the ’90s and looking back at the ’60s there’s a 30-year disparity there. You’re looking at the beginning of Bob Marley, Cream, The Stones and The Beatles – all of these people I had a mad life with, and then in 2020 you suddenly realise it’s been 30 years since the ’90s.

“I can go to a club this weekend and play music that’s 25 years old and people will still say, ‘what the fuck is this tune?’, because the music from that period was so cutting edge it created the bastard child of electronic music, which is drum&bass.

I’m really not about presets, because if I’ve got them some other fucker’s got them

“Some people went off and used it very commercially, like most genres, but most people I speak to at the cheese counter at Waitrose say, ‘I used to love Metalheadz but stopped after 20 releases cos I wanted to have kids’, whereas I’m just a professional child who carried on making music. If you’d never listened to Timeless, you could pop Subjective tracks like Dollis Hill and Reflection in there and they would sit well.”

JD: “On Music for Inanimate Objects, we didn’t have a game plan, we just wrote what we wanted to write and the process was a stream of consciousness. For the second album, The Start of No Regret, it was more considered.”

Goldie: “I’d been very successful writing vocals and we felt that was missing in our partnership. James would go hell for leather on certain pieces but I thought they would be very difficult to write a vocal to.

“The album was initially going to be called The Art of Simple Complexity [laughs], but what Tongy infused in the project was to put a little more ID on it. All the vocal tracks are really personal and I feel the track arrangement is really good because the album starts getting pacier as it moves forward.”

Did making this album in the middle of a pandemic change your working process?

Goldie: “We kind of dodged it really. This was James’ seventh trip to Thailand, but what changed was that he had an unbelievable desire to write in isolation at hotels before we got out of quarantine. We had all these sketches that we’d bounced around, but he also made new ones while he was twiddling his thumbs and getting really bored. Breakout was one of them, and Paradise, so we thought fucking hell, let’s go into those.”

Were the vocal contributions more complex to source?

Goldie: “Vocal-wise we work remotely most of the time because I have to record the vocal guide. It’s that Kubrick thing where I won’t have any of it; there’s the vocal, there’s the guide, there’s the intonation of the vocal and it’s got to be sung in that way.

“After they’ve nailed that they can go off-piste and freestyle as much as they like, but I can’t stand the idea of divas. Lyrically, Crazy, Brushstrokes and American Gods were made on Necker Island one hour and a half out of Phuket three and half years ago. I’ve got a summer house there, so we just made fires and wrote those tracks.”

I built an SSL 4000 Series compressor and embedded it into a fruit bowl, and I’ve made 50% of the modules in my modular rack

JD: “As Goldie says, he did the lion’s share of the lyrics and if we ever fall out I can release all of the demos of him singing from start to finish. Basically, if I come up with a little chord structure for a song and play it to him, we have to hit record there and then.

“What’s funny about Goldie is that he’ll sing a top line into his phone, save it, and two years later I’ll play him the same chord and he’ll sing the same top line again. At one point we were playing with drones and different bits of software and he sang a line that resonated so strongly that we made it the lead and ditched The Art of Simple Complexity title to create what became The Start of No Regret.”

Did you have a black book of vocalists you wanted to work with or did the music inform those decisions?

JD: “Once we’ve written a track we know who we want on there and generally turn to Goldie’s pool of friends and trusted people. Greentea Peng was different. I’m a Spurs fan and Goldie’s friend, graffiti writer Drax, is an Arsenal fan, so a couple of years ago we went to the pub to watch the North London derby and he told us his goddaughter was Greentea Peng.

The worst thing for Goldie is for me to be spending time EQing out little resonances because it’s a complete vibe killer

“This was before she got signed and he played us something on his phone that we thought was sick, so I grabbed her WhatsApp and that’s how the whole collaboration developed.”

Being a sound engineer, would you say your studio in Bournemouth is a little more expansive than Goldie’s?

JD: “For sure. We track and record everything through Goldie’s Neumann U47 mic and he has a nice Focusrite ISA One preamp, but I trust my room too much not to mix at home.

“When we’re together, I’ll write as quickly as possible using some samples and rough chords and we’ll usually get a track done in a day and all the edits finished by lunchtime the next day before moving on. The worst thing for Goldie is for me to be spending time EQing out little resonances because it’s a complete vibe killer.”

Is it problematic exchanging sound files when you both have different monitor setups?

JD: “We’re sending them back and forth way before that. Goldie will send my chords having had them come out of his speakers and into his iPhone while he’s hitting voice record and singing over the top of them. We know what each other expects and if I send him an early track he’ll be listening to the bass notes and the timing, not the levels.

“When it comes to checking the mixes, he’s very particular about the bass and vocals and how they’re coming through. He wants everything to sound Motown, where the mic’s fucked and everything’s distorted but sounds nice.”

Goldie, did you streamline your studio when you moved to Thailand and rely on old-school gear that you knew worked for you?

Goldie: “No, I boxed up all the rackmount stuff and my Korg M1 and 808 from where I was in Bovingdon in Hertfordshire. Since then, James brought a lot of software to the table. Any good music composition is 20% hardware, 20% software and 60% soul.

Any good music composition is 20% hardware, 20% software and 60% soul

“With my dyslexia, I could never retain information on a binary level. I didn’t feel the necessity to either, because I’ve got mad concepts that I write down in books. You can look at a screen, but you’ve also got to look at the bigger canvas and that’s my strength in working with composite music.

“Of course, Logic comes out with new stuff that we update all the time and James shows me plugins where I think, really? We used to have to do all that manually. I’m really not about presets, because if I’ve got them some other fucker’s got them.”

Do you feel that, today, electronic producers are too preoccupied with the technicalities of music-making and lack vision?

Goldie: “I think content is really important to music going forward. When I think about what’s come out over the past 15 years from a software point of view I listen to the music and think, pfft, what are you doing with it? I’m hearing a lot of the mechanics but I don’t want to hear the mechanics, the trick is to hear the soul and to make engineers ask, ‘What the fuck have they done there?’.

“James has that tech ability, but his programming goes beyond just being a tech and he’s really learned how to walk that rope. I don’t wanna give it the big uncle, but I keep throwing kitchen sinks at him and he doesn’t flinch.”

James, Goldie mentioned earlier that you build your own gear?

JD: “Before I did music full-time I worked for 13 years as a flight simulator engineer and had a background in electronics. I built an SSL 4000 Series compressor and embedded it into a fruit bowl and I’ve made 50% of the modules in my modular rack.

“Some of the designs are open source, so I’d start with a multiband filter and get together with a group of people from a Facebook group to buy the circuit boards and capacitors and design the faceplates. From there, I went on to learn how to flow STM microchips and that turned into an addiction. I’m basically adapting stuff that’s already been made.”

Does using modular slow you down?

JD: “I don’t track kicks or synth lines into a tune, I’ll just hit record on my DAW, mess about for half an hour, stop, cut up all the bits I want, save them and start again. Otherwise you can easily end up with a three-hour audio file and you’re probably not going to go back through all of that.

“I’ve also learned not to record pre-effects. I’ve got a Mackie 1604-VLZ Pro and smashing the gains on that and clipping is the key to a lot of my distortion and basses, but if you do that too much everything sounds washed out and unusable later on.”

Goldie, is it fair to say that you come from a world that was based on the limitations of ’90s gear?

Goldie: “I do what graffiti did, where you’ve only got a certain amount of colours so you’ve got to really use them in the event window of what the arrangement is. I had a critic a couple of years ago, which is where the name Subjective came from, who said ,‘What the fuck has DnB’s three notes got to do with anything?’.

There’s so much technology out there that you get this sweet shop syndrome where too much of it is kind of making us sick

“Well in its primitive form, jazz has got three denominate notes, so it’s really all about what you do with them. A lot of people within electronic music discard the writing side of it and think in terms of numbers. Music is math, but it’s not just sound, there are different dynamics relating to how sound interacts with what’s around it.”

JD: “When you’re working on a Rufige Kru DnB roller that you want all the DJs to play, you have to fall back on the maths, but when it comes to creating a Subjective track like Lost or The Start of No Regret, you have to discard that and unlearn what you know about instrumentation.

“As Goldie once said, imagine there’s a band playing at Ronnie Scott’s and someone’s about to do a solo, everyone else drops back and the shine moves to that person. That’s the approach we take to mixing the tracks, where I’m literally automating the volume and EQ curves depending on where we want the focus to be.”

Goldie: “Because I don’t engineer and James is a geek, we have a great yin and yang. When we wrote the track Silent Running, I watched Bruce Dern and the three robots, turned the music up and whatever the NASA feed had going on to see how endearing the music sounded with that backdrop.”

We don’t seem to have many long-lasting electronic genres surfacing these days. Is that a good thing or does it show a lack of imagination?

Goldie: “It does show a lack of imagination. We’re in a dip but it’s very hard for any genre to rear its head and be absolute because everything’s been done and there are not many technology changes that can evoke new genres. We also have a 100-year time machine of things to take from.

“We’re pushing the envelope in that I feel The Start of No Regret is abstract or Portrait, on the previous album, is about a track writing itself, so there are many creative ideas that people aren’t doing. There’s lots of room for innovation, but people aren’t joyriding the equipment the way they should.

“There’s so much technology out there that you get this sweet shop syndrome where too much of it is kind of making us sick. Just get the basic flavours and execute the flavours instead of putting a plugin on top of another plugin. You can polish a table with three legs as much as you like, but it’s not going to have the right balance and you can’t hide that.

“To answer the question as best I can, there’s not enough people going balls out and doing stuff that’s eclectic, but hopefully we’re at the beginning of electronic music doing something really new as opposed to the end of it.”

Is some of it to do with fear and producers conforming to how music is consumed these days?

Goldie: “They’re very frightened. When I say ‘LP’ to people, they lose their shit and Spotify, for all it’s worth, can have all the icing in the world but without the cake it doesn’t really matter. What was the last album you listened to over the past 10 years?

“I think you might find it’s the same as me because I’ve been listening to the same albums on repeat since pretty much forever. I probably listen to Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue once a month, Pat Metheny’s Still Life (Talking) once per week, Charles Mingus or new stuff like Cranes. We all stopped listening to Coldplay after the first album. Thom Yorke was a god in my eyes – Radiohead were the first electronic rock band if you like, because they were pushing the envelope with pedals and looping.”

JD: “One of the few albums I listen to from start to finish is Tyler, the Creator, and Burial is also someone who managed to find a new aesthetic over the past 15 years.”

Goldie: “Lovely boy, but he didn’t want to move into anything else and just wanted to do his own thing. He had a great technique using edit windows that he couldn’t go back on. And Will [Bevan] was one of the last of the greats in terms of someone who didn’t give a fuck. Grime’s now at the forefront in terms of Britain having its first real rap music where something’s also happening socially and politically.”

You’re clearly in simpatico, so where does Subjective move from here?

Goldie: “We don’t just pick something up, put it down and leave it – we’ve got lots of folders that we can’t wait to get out there. We’ve got Sea Of Tears – the orchestral version – ready to go and mad versions of different things that we can’t wait to get into, like mixing a soundtrack album.

“You’re only as good as your music and no one’s bigger than that. All my heroes are fucking dead, so it’s good to ask what you’ll leave behind. When the spirit of music is kept alive through me listening to it or reminiscing, that’s the best thing.”

Subjective's new album, The Start of No Regret, is out May 20 on Three Six Zero Recordings.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.