“We did turn a corner. But it must have been the biggest corner in the universe, ‘cos it took ages to turn it”: Inside the protracted creation and glorious guitar work of The Stone Roses' Second Coming

It took the band 347 ten-hour days in the studio to produce 75 minutes of music, but the definition of difficult second album saw a darker Zeppelin-esque Les Paul-toting John Squire emerge

Few second albums have carried such a weight of expectation as Second Coming, the Stone Roses’ massively anticipated follow-up to their majestic eponymous debut. This ‘difficult’ second album was released a staggering five and a half years after their self-titled record, a stretch of time so epic that the British music scene had changed beyond recognition by the time it was finally released on 5 December, 1994.

The band had emerged in the late '80s amid the feel-good hedonism of ‘Madchester’ rave culture, blending the psychedelic 60s jangle of The Byrds with a deep groove. They re-emerged into a music scene dominated by the advent of Britpop.

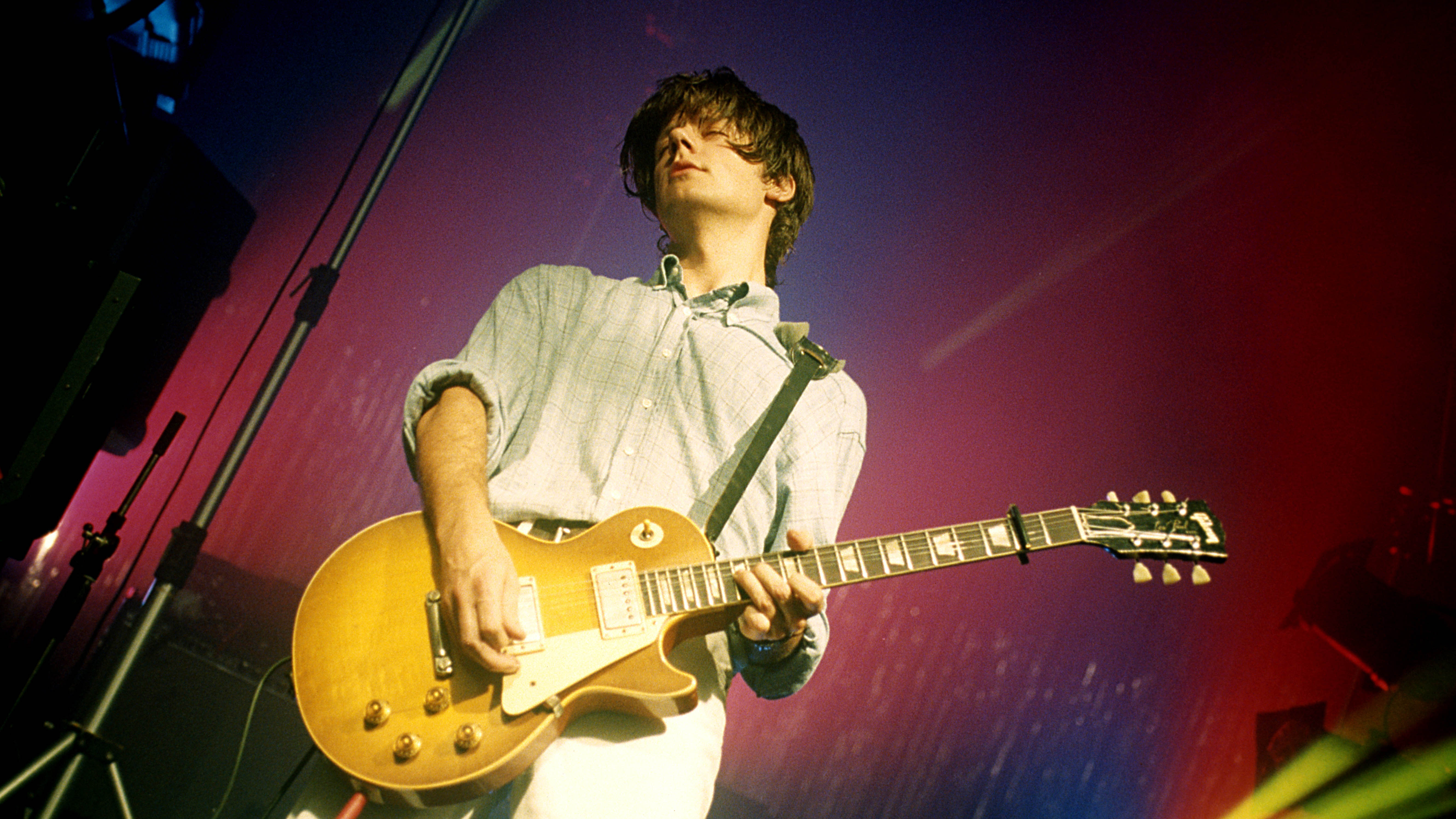

On Second Coming, the band – vocalist Ian Brown, guitarist John Squire, bassist Gary 'Mani' Mounfield and drummer Alan ‘Reni’ Wren – turned their backs on their dreamy pop sound, with Squire taking the reins and drawing on the '70s blues-rock of Led Zeppelin. This was the album on which the guitarist embraced the sound and feel of a Les Paul. The result is a much darker album, with the guitarist's assured playing and thick, crunching tones notable on the likes of Driving South, Love Spreads and the expansive 11:19 minutes of Breaking Into Heaven.

The Stone Roses’ eponymous debut album became the soundtrack of a generation and their heady ascent culminated in an outdoor concert in May 1990 in front of 27,000 people at Spike Island, dubbed ‘Woodstock for the baggy generation’. Their future looked assured.

We all went to the south of France and hired a helicopter and stayed in £500-a-night hotels for a few weeks

Mani

But it all juddered to a halt when they became involved in a two-year legal battle with their label Silvertone. An injunction taken out against the band in September 1990 prevented them from recording with any other label. In May 1991, a court ruled in the band’s favour and they eventually signed a reported multi-million deal with Geffen Records.

According to an interview in Uncut in February 1995, each member received a £100,000 advance. They promptly took the rest of the year off. "We all went to the south of France and hired a helicopter and stayed in £500-a-night hotels for a few weeks,” bassist Mani told Mojo magazine. “We went, ‘Right, let’s fuck off and spend some money’."

The advance helped John Squire to acquire a 1959 sunburst Les Paul Standard, previously owned by Cosmo Verrico of the Heavy Metal Kids. This was a guitar that would feature heavily on Second Coming and define the sound. In an interview with Guitarist magazine in February 2024, Squire said Jimmy Page once asked him whether Gibson had been in touch with him about a signature model in light of his patronage of Les Pauls in the Roses and later with The Seahorses. “No,” replied Squire, “maybe I play too many Strats.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In March 1992, in a bid to avoid the usual studio locations, the band relocated to a centuries-old 12-bedroomed house and estate of Ewloe, north Wales. Producer John Leckie – who worked on The Stone Roses' debut – hired the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio and installed it in the cellars of the house.

The first four weeks were productive. The band arrived with new songs Breaking Into Heaven, Love Spreads, Driving South and Ten Storey Love Song, all written by John Squire. On Easter Monday, Leckie and the band watched the film Zulu on TV, with Leckie recording the mesmerising tribal drum pattern in the film, with a microphone, direct from the TV.

They decided to use it on the four-minute intro of Breaking Into Heaven, the album’s opening track. Squire created layers of feedback guitar on his Les Paul to produce harmonies, which were then manipulated.

The Stone Roses had always been a well-rehearsed live outfit but by this point, they hadn’t played together since the legal battle with their label. Their efforts were hampered by the confines of their recording space.

“Because we worked in the cellars of the house, you couldn’t set up like you would in a normal studio,” recalled John Leckie in a 2011 feature on the album in Clash magazine.

But after an encouraging start, work faltered and stalled. What followed was 18 months of inertia, with the band indulging in new pastimes such as archery.

By the time we got to the studio, it would be 10 or 11 o’clock at night

To complicate matters for Leckie, in early 1993 the band began using a studio called Square One in Bury and moved into a shared house in Marple, near Stockport, lent to them by a local millionaire. The band rehearsed there sporadically for six months.

“It had electronic gates, a snooker room, indoor pool, a sauna and Jacuzzi,” Mani explained to Mojo. “It was a loafer’s paradise.”

For Leckie, that whole period was a disaster. “By the time we got to the studio, it would be 10 or 11 o’clock at night. Eventually I said, ‘For fuck’s sake, let’s get up at 11 o’clock in the morning, or lunchtime. Let’s try and get here by four’. They’d say, ‘Oh yeah, we’ll do that tomorrow, definitely. We’ll have an early night, get up at 12, have a good lunch.’

"They had a chef at the house. And then it’d be three, four, five o’clock, and lan would come and say, ‘What’s happening?’. You can’t change people. That’s what Reni always used to say: ‘You’re never going to change us, no matter what you do’.”

Leckie quit and was replaced for a short period by engineer Paul Schroeder, who took over as producer until he also left, in February 1994. The band then appointed Rockfield’s in-house engineer Simon Dawson as producer. His brief was simple: “The idea for the album was for it to be quite live,” Dawson reflected to Mojo. “Played as a band. It was all about groove rather than the perfect studio take.”

They finally started to make progress. “Things started to get done,” recalled Mani to Mojo magazine. “We did turn a corner. But it must have been the biggest corner in the universe, ‘cos it took ages to turn it.”

John Leckie’s work wasn’t wasted. Elements such as the long intro to Breaking Into Heaven were retained, as were the drum tracks for Ten Storey Love Song and How Do You Sleep. Dawson told Sound On Sound that he found it relatively straightforward to blend the feel of the older takes with the new material.

“In terms of feel, the way the guys had been recording was very live, and that's where I was coming from, so that wasn't difficult.”

The basic guitar sound is dead easy really

Simon Dawson, producer

The 70s influence of Zeppelin and The Allman Brothers Band was evident on the emerging tracks. This was Squire’s guitar album, on which he showcased his inspirational playing.

On the band’s debut album, one of Squire’s go-to guitars had been a 1960 Shell Pink Stratocaster, an instrument whose out-of-phase jangling tones elevated tracks such as I Am The Resurrection and She Bangs The Drums.

The Strat was used on Second Coming, but it was Squire's newly acquired ‘59 ‘burst Les Paul Standard that really dominated the album. "The basic guitar sound is dead easy really,” Simon Dawson told Matt Bell of Sound On Sound magazine in May, 1995. “All you need is a '59 Les Paul guitar, a nice old Fender Twin amp that's been hot‑wired, and a Shure SM57 and Sennheiser 421 to mic up each speaker. You send it through a dbx160 compressor, and then straight into the desk. Oh, and you need someone who can play, of course!”

The crystal clear chime and serious headroom of Squire’s 1982 Fender Twin provided the perfect base on which to build.

Dawson told Sound On Sound that he and Squire experimented with various set-ups at Rockfield, but said the Les Paul and the Twin was the one that gave them the sound they were happiest with. “For most of the album, that's all it is. John's got some pedals as well — an old Echoplex, and an Electric Mistress. They were used quite a lot, but the basic sound was really simple… We also used an Orange amp and Orange cab for some of the more distorted sounds, the Hendrix‑type bits, and John also used a pink Strat, but those were his two main guitars."

As for the bass, Mani used his trademark Rickenbacker 4005 – with its dramatic Jackson Pollock-style paint splattered finish – through a Mesa Boogie amp and cab.

"Mani likes his bass to be round and warm‑sounding,” recalled Dawson. “He's quite into the reggae bass sound."

Despite nearly all the false starts and time-wasting, the band really nailed their live performances at Rockfield – although the pace was often slow. In a piece in Spin magazine in May 1995, writer Simon Reynolds noted that it took the band 347 ten-hour days in the studio to produce 75 minutes of music. As Ian Brown told Reynolds: “Maybe 50 of them days would just be us getting stoned listening to our favourite records through the studio system.”

Squire was the creative driving force on Second Coming, writing all but three of the tracks on the album. The rhythm section of Mani and Reni on bass and drums respectively was as fluid and locked-in as ever on stand-out tracks such as the dynamic electronic-crossover of Begging You and the languid Daybreak. Brown’s vocals really shine on the blues orientated Zep/Madchester fusion of Driving South. Ten Storey Love Song meanwhile, with its powerful pop sensibilities, harks back to the band’s Byrds-influenced era, while How Do You Sleep is the album’s catchiest track.

Love Spreads is the undoubted masterpiece of the album, with its infectious blues rock swagger and deep, dark groove. Released as the first single from the album, it reached No. 2 in the UK Singles Charts.

The Second Coming was finally released on 5 December 1994 and was met by wildly mixed reviews. Rolling Stone gave it two out of five stars, describing the album as “tuneless retro-psychedelic grooves bloated to six-plus minutes in length”.

But others saw redeeming features in the album. The Los Angeles Times praised Squire’s “captivating guitar work which recalls the bluesy side of Jimmy Page and Duane Allman”.

Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic also highlighted the merits of The Second Coming. “The Stone Roses create a dense tapestry of interweaving guitars and pulsing bass grooves,” he wrote. “It might not be the long-awaited masterpiece it was rumoured to be, but Second Coming is a fine sophomore effort.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

MusicRadar deals of the week: I'm feeling this! Score an impressive £350 off the Fender DeLonge Starcaster, as well as hundreds off Epiphone, Gretsch, Gibson and more

“A fully playable electro-mechanical synth voice that tracks the pitch of your playing in real time”: Gamechanger Audio unveils the Motor Pedal – a real synth pedal with a “multi-modal gas pedal”