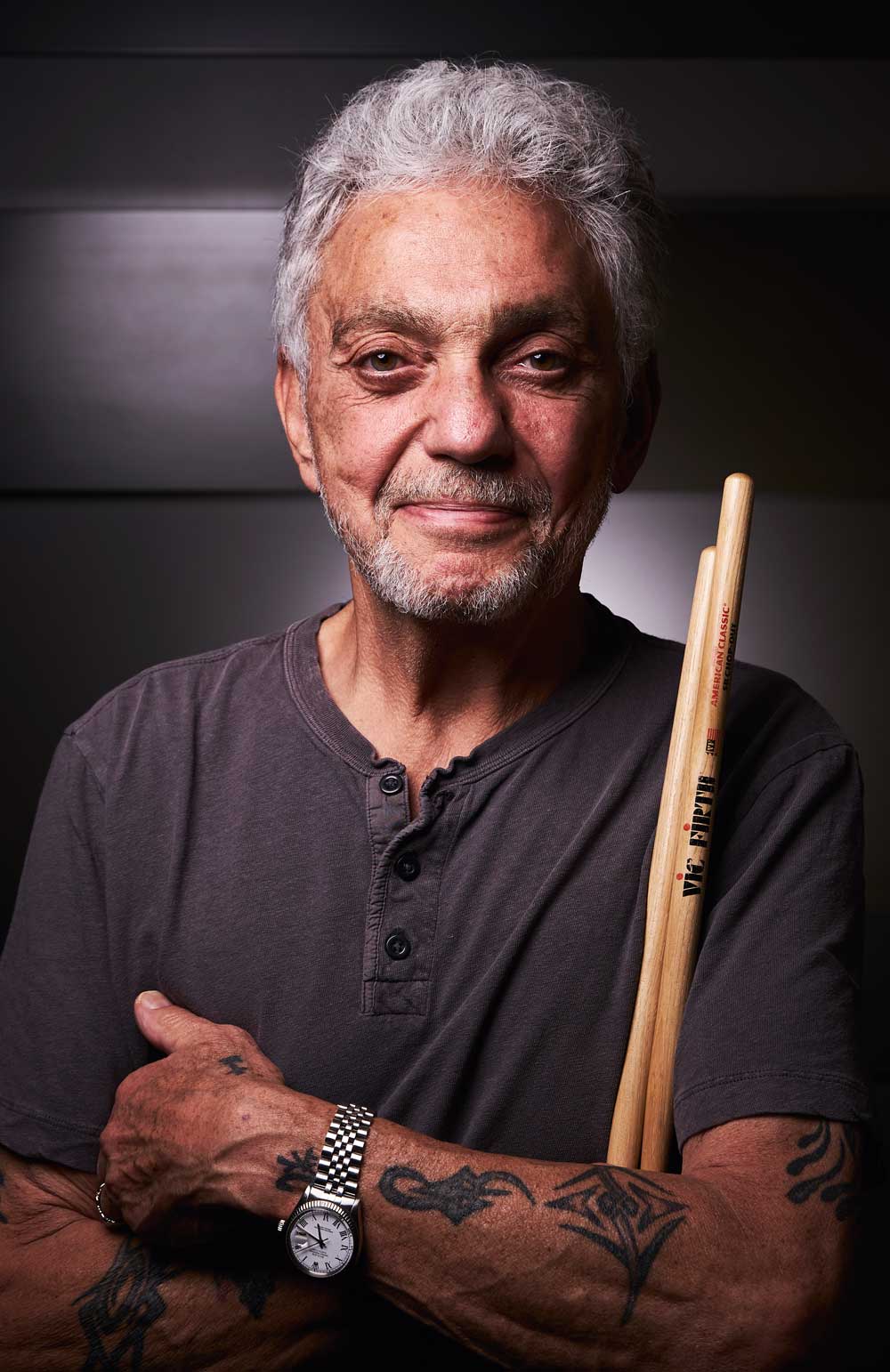

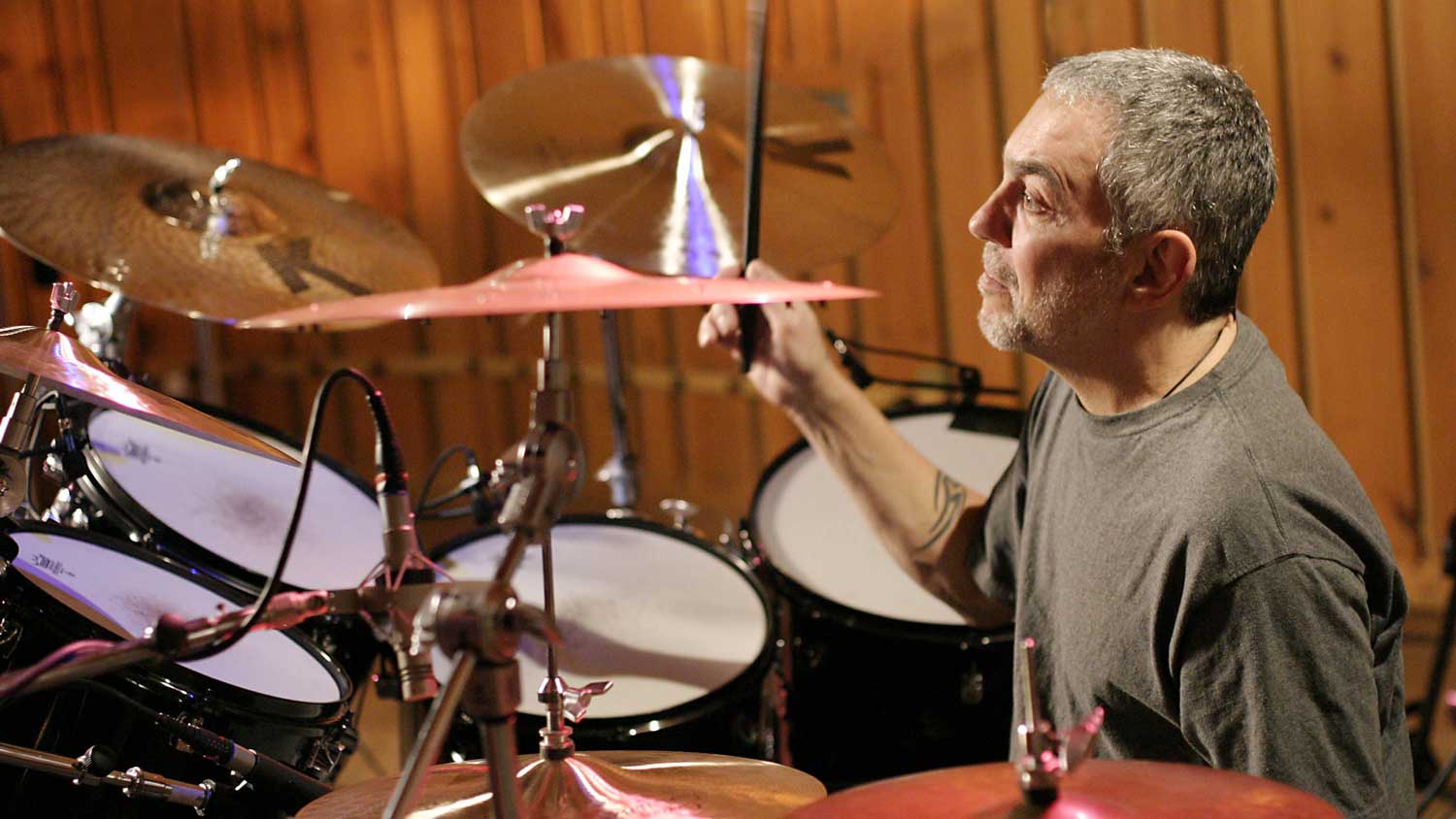

Steve Gadd: the drummer's drummer

One of the most influential and imitated drummers of his generation talks to MusicRadar

There are a lot of ways to describe Dr Steve Gadd.

He’s a drummer’s drummer, someone admired by his contemporaries from across the musical spectrum. But then he’s also a songwriter’s drummer, with a matchless list of credits for the likes of Paul McCartney, James Taylor, Paul Simon and Jim Croce. In addition to his distinctive feel on the drums, one of Gadd’s most impressive attributes is his versatility.

He’s played on jazz sessions for legendary recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder in New York in the 1970s, but he was equally at home working with fusion heavyweights such as Chick Corea and Al Di Meola. He’s recorded with Frank Sinatra, opera star Luciano Pavarotti, played the blues with Eric Clapton, and laid down R&B/disco grooves for Diana Ross. In the 1970s and ’80s, he never seemed to be out of a recording studio, and he helped Yamaha develop the Recording Custom Series.

There came a point where it seemed like every drummer in the world wanted to replicate Gadd’s sound and style.

There came a point where it seemed like every drummer in the world wanted to replicate Gadd’s sound and style, and every producer out there wanted him on their sessions. Now in his seventies, Gadd still maintains a tireless playing and touring schedule.

When we catch up with him, he’s in London ahead of a performance in Hyde Park with James Taylor, but he’s also juggling his high-profile sideman gigs with Taylor and Eric Clapton with jazz club tours where he leads his own Steve Gadd Band.

While the changing nature of the recording industry has cooled down the once thriving session scene, Gadd continues to record new material, and 2018 has already seen the release of Chinese Butterfly from the Corea Gadd Band and Omara from Blicher Hemmer Gadd.

Despite all his accomplishments, in person Gadd has no airs or graces – he is relaxed and approachable while still passionate about the art form of which he remains both a master and an insatiably curious explorer.

In recent years you seem to be spending more time as a bandleader with the Steve Gadd Band. Is this part of your changing role as a musician? Do you enjoy being the leader?

“I enjoy that. If I have my own projects, first of all I can get to choose the music that I want to play, but it also helps me have a little more control of my own schedule too. I do a lot of work on the road, not as much studio stuff, and you’re constantly putting the puzzle together to try to make the schedule work, but having my own thing helps me have a little bit more say in the big picture.”

After so many years playing sessions, you must have a huge network of players you can call upon when you want to record.

“I don’t really think about it that way. This thing happened pretty naturally – this band. I’ve been playing with James Taylor on and off for 15, 20 years, and this band – Michael Landau, Jimmy Johnson, Walt Fowler…

"Before, it was Larry Goldings in the band, now Kevin Hays is doing it – it’s James’ band and we had been playing together so much our wives thought it would probably be a good idea to do our own thing because we enjoyed hanging out together and because we enjoy playing music together.

"So that was how that evolved. It’s not like I sit around thinking about putting different bands together, this thing sort of happened and it felt really good, so that’s how it came about.”

Is the song-writing process very collaborative for the Steve Gadd Band?

“We pull in ideas from everybody no matter who wrote the thing. We do some things as a band in the studio, but for the most part guys write songs and bring them in, they play them for me, I listen and see which ones I feel are going to work and which ones aren’t going to work.

"On this last album, I collaborated on a song with Walt Fowler and Larry Goldings. We had the time to go over to Larry’s house and start working on some things together. I haven’t really been writing on my own so that doesn’t happen often.

"Also my son Duke wrote a song and collaborated with Mike Landau and Kevin Hays, so in four CDs that’s the first time that’s happened. It’s good; the evolution of the band is good.”

You’ve been with Yamaha drums for such a long time. Does your set-up ever change?

“I change heads, I go through phases where I’ll use Clear Ambassadors on the bottom of the toms, or Coated Ambassadors on the bottom of the toms, I go through things like that. I’ve gone through using Clear Pinstripe heads on the toms and now I’m using Coated Ambassadors, but it’s not like I change them for each thing.

"I might tune them differently for each thing but now I’m going through this phase where it feels good with the Coated heads and I’ve been doing it for a while. I don’t know when that’ll change. Every once in a while you’ve got to do some spring cleaning and change it up a little bit, but what I do for the gigs is tune the drums a little different. That’s the way it works for me.”

[With hi-hats] not only how they sound, but how they feel is important.

Do you spring clean your cymbal set-up from time to time, or are you sticking with the K Customs you’re using?

“I’ve been using these cymbals for a while. A lot of my gear is in New York and I live in Arizona, so it’s not like I have a lot of time to go through everything that I have. I just haven’t had that luxury. I’ve found some cymbals that work for a lot of different things and I might change a ride or something or a crash, but for the most part I use the same ones. And I’m always looking for new hi-hats.”

Why the hi-hats in particular?

“You get a pair that work for a while. I had a pair that I used for a year and the centre hole on the top cymbal got bigger and I couldn’t centre it, so I couldn’t control the ‘chick’ when I was playing it with my foot.

"I’ve got some different ones that I’ve found, not a pair, they’re different combinations that work, but one of the cymbals is thick and one is thinner, and a lot of times the thinner cymbals will fatigue out.

"They’ll lose their vibrancy and that affects how it feels especially when you use it with the foot, so I’m just always on the lookout for some things that feel comfortable. Not only how they sound, but how they feel is important.”

In the heyday of playing sessions in the ’70s, when people called you in, did they want you to bring your own sound or to be a chameleon and match yourself to that session?

“I think it was the latter: just come in and give them what they’re looking for. A lot of the studios in the ’70s had their own bass drum and toms already set up in the room.

"You’d just bring a trap case and cymbals. People didn’t start really moving their own gear or having it moved until the ’80s.”

I got to see Krupa as close as I am to you. I brought a little kit in and he let me play with his band – he played my little drums.

Was there a moment when you realised your career had taken off? Did your success have a big impact on your life?

“Not thinking about it like that, I got busy and I loved what I was doing. There was so much going on back then that I didn’t really take the time or have the time to think about the impact. I never thought about what the impact was going to be or how it’s impacting my life.

"I was happy to be working and making a living playing music, that was all I ever wanted to do, but now looking back I can see how lucky I was and how fortunate I still am. The impact of what I’ve done, how it has affected people, I get to see that because I run into people and they tell me. But it isn’t anything that I planned on.”

Given the sheer volume of music you recorded, do you ever hear a song on the radio and think, ‘Is that me?’

“Yeah it does happen. Some things I know it was me and then there are certain things I have to ask my wife, ‘Who was playing on that?’ It could have been somebody else – I definitely don’t remember everything that I did.”

Was there a sense of camaraderie – or even rivalry – between the top session guys, like yourself, Jeff Porcaro and Jim Keltner?

“Only a camaraderie. For me, there was a deep respect and love for their musicianship and gratefulness for what I’ve learned from them. I go in the studio and I hear the music and it makes me think immediately, ‘How would Elvin play this? How would Keltner play this?’ Those things are inspirations to come up with parts for whatever you’re doing, so it’s a camaraderie.”

Did you ever get to meet your heroes, such as Elvin Jones and Max Roach?

“I did. My parents and my grandparents and my uncle used to take me to hear all those guys when I was a kid. Art Blakey, Max Roach, Gene Krupa. I got to see Krupa as close as I am to you. I brought a little kit in and he let me play with his band – he played my little drums. They would come through town every six months.

"The way the circuit was back in those days, there weren’t a lot of big concert halls for jazz, it was more of a club thing. The clubs were nice and some of them seated quite a few people but it wasn’t theatres in those days, so you could sit up close and get to meet these guys.

"They’d come through a few times a year, so they’d remember you when you came back to see them. Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Carmen McRae, Ray Bryant, Tommy Bryant, Slam Stewart.

"I had the opportunity to see those guys and sit in with them when I was kid and then later on, after I had been recording and sort of making a name for myself, I’d run into Elvin or people I had met when I was a kid and it was nice to see them later and they’d remember me and be happy for me. So yeah, our paths did cross.”

You did a lot in the ’70s with the guys from Return To Forever – Chick Corea, Stanley Clarke and Al Di Meola. At that point, were you aware that the music had changed, that this wasn’t bebop or hard bop anymore?

“I was just playing music. I grew up loving the drums with a supportive family that encouraged me to do whatever they thought I was interested in musically as long as they thought it wasn’t bad for me. Drum corps, taking lessons, playing in the school band, playing in the jazz band, they’d take me to hear all the different groups when they came into town.

"When I got a little older there was a club that used to bring in organ groups and my dad would take me there, and in all these places I’d sit in. I loved it all. I love music. However it was evolving, whatever I had listened to growing up and all the different styles that I loved and practised growing up, I was able to apply that to what young guys were composing.

"It just sort of happened. I wasn’t really conscious of how it was evolving other than it went from straight-ahead to more of a backbeat. But then the backbeat thing got into fusion, so it was more backbeat with jazz. That’s how I approached it. Not the evolution of it, just enjoying the music.”

It isn’t just about one thing. It’s about everything.

You took dance lessons as a youngster – there’s a small but elite group of guys who could tap dance and play drums – Buddy Rich, Sammy Davis Jr…

“Yeah, my brother and I used to tap dance. Sammy Davis was a great tap dancer. That’s a whole other art in itself.”

Did that feed into your playing?

“I think that anything you do rhythmically and musically, no matter if it’s on a different instrument, it will have an affect on what your main thing is. Tap dancing is a great art form and I’ve seen some guys that were so innovative, just like guys are innovative on the drums, these guys came up with their own thing.

"There was a lot of camaraderie there, dancers watching other dancers, sharing ideas or copying what the other guys were doing. I never got into it as much as I would have liked to, but when I see the masters do it, I’m still really inspired by that stuff. I’d still love to be able to do it.”

You’re renowned for taking different groupings and moving them around the bar and splitting them up between your limbs. Where did that come from?

“I think the origin of that came from spending a lot of time at the instrument and constantly trying to evolve. I’m still learning.

"You could take one simple rudiment, like a flam paradiddle with a tap, you could take that same thing and when you displace it to different parts of the bar, even though it’s the same thing technically, you have to make an adjustment because the ‘1’ that started on the right foot, when you displace it it’s not on the right foot anymore.

"It’s like another kind of independence. And what’s nice about that is you can take one thing and then it becomes different things, so you’re not trying to do too many things at the same time.

"I try to think of things like that, work on bass drum technique, and I think when I practise I try to play in phrases. If I’m doing rudimental things I try to keep it in two bar phrases. If I’m trying to play more musical things, I’ll think in four or eight bar phrases.

"I’ll try to do things like solo for four bars, then try to repeat the same thing for four bars. There are different ways of repeating yourself while working on different things. That’s the way I practise now. That’s what I’ve learned to do over the years.”

Is practice still important?

“Yeah. The fact that I’m playing a lot, I don’t feel like I need to practise to stay in shape, but if I’m not working I need to do something to stay connected to the instrument and then also it’s nice when you have some time to sit there and try some different things over and over again, really work on the things I was talking to you about.

"These are ideas that I have and I try them when I’m warming up for a gig or something, but they turn into other things when you can sit behind the drum and try them on different instruments. So yeah, I think practice is important. And exercise is important for playing drums.

"If I can keep myself physically fit, I might be playing a gig where it doesn’t really require a lot of stamina, but there could be another gig coming up that does require a lot of stamina and the only way to keep yourself in shape for that is you’ve got to keep warming up every day so your muscles don’t get tight, but you’ve got to stay on a certain level physically and with cardio, especially when you get older.

"When you’re younger you can get away with stuff, but when you get a little bit older, you can feel the effect of time.”

Do you still enjoy the rigours of touring?

“The rigours of touring, no one enjoys that, but I enjoy and really try not to take for granted the guys that I’m playing with and the music that we play and the love that we share, the respect we share with each other and I’m grateful for the fact that I play.

I really play for a living.

"We have fun out there but travelling and getting from one place to the other, we fly over here and then we do it by bus, it’s the best that it can be, but it takes its toll after a while. It’s hard but it’s worth it because all of the good stuff makes you forget about all the other things.”

You first recorded with Chick Corea in 1975 and you released an album together, Chinese Butterfly, this year. With these long-term musical relationships, you can’t be the same people or the same players now that you both were in the ’70s?

“You know what, I run into people that I’ve worked with over the years and it’s like we just pick up right where we left off. That’s the way it’s been for me.

"You become part of each other and you remember certain things that are important about individuals and you just go back and start there again and see how it evolves. But the connection is always easy.”

You’ve worked with so many great bassists. Has anyone’s feel or sense of time surprised you? Or has anyone instantly clicked with you?

“All of the above. With music, you’re always playing with different people so you’re constantly making adjustments. It’s not like you go in saying, ‘This is me, you’ve got to adjust to that.’

"We’ve all got to adjust to each other and that’s what makes it challenging and interesting and rewarding in a way where you can share things with people that are willing to give in, compromise, they’re willing to try and understand. Some of them you just lock in with. The other thing that happens is you’re constantly dealing with sound if you’re not in the studio.

"If you’re in an auditorium with a PA, you’ve got to have the monitor right to be able to lock in with the guy. Having good sound is important to how everything feels together too. There are so many variables. You get to know people by not only how well they play but how well they can adapt to different situations, because if they say, ‘Fuck it, I can’t do this anymore,’ that poisons the well for trying to get where you want to get to musically.”

So many drummers cite you as an inspiration: do you ever feel like you’re under a microscope?

“I always try to play the best that I can for the music that I’m playing and I love playing, so I try to keep myself fit and ready to play. The other thing is just try to be a nice person, because that’s what you want, that’s what I’d like people to remember. If I could help someone I would, if I could show somebody something, I’d show them.

"If I had something, I’d give it. Just trying to be as good as I could as a person as I try to be as a drummer. I think that’s important. I might not be doing innovative things today like I did before, but if someone asks me about something,

I can be innovative in the way I take the time to talk to them and share with them. It isn’t just about one thing. It’s about everything.”