“He used little gear, took a low fee, and let the band and their music do the talking - and if he could do it all in one take, so much the better”: The genius of 'anti-producer' Steve Albini

This month in our Pioneers series, we explore the influence of an engineer whose uncompromising approach helped to shape the sound of albums from Nirvana, Pixies and PJ Harvey

In our Pioneers series, we illuminate the genius of the most influential artists and producers in musical history. This month, we're talking Steve Albini, a musician, producer and engineer whose uncompromising approach helped to shape the sound of albums from Nirvana, Pixies and PJ Harvey.

You may wonder why MusicRadar – a website that would rather holiday at a synth-packed and rain-soaked Superbooth in Berlin than lay on a beach in Bermuda sipping cocktails – would put Steve Albini, a famously stubborn anti-studio-tech producer (in fact, a famously stubborn anti-producer) on any kind of pioneer-labelled pedestal.

Well, just as superheroes don't always wear capes, so pioneering studio whiz-kids don't always use the latest 3D soft synths, cathedral-modelling convolution reverbs, 200GB orchestral libraries, and AI. Steve Albini didn't go anywhere near any of that lot in his production career, nor did he even – according to him – have a production career. But it's this kind of anti-establishment, anti-technology, anti-normality attitude that actually made Albini such a studio pioneer.

Albini used little gear, took a low fee, and let the band and their music do the talking. And if he could do it all in one take, so much the better

So while most 21st-century producers like to surround themselves with a console full of the latest outboard gear, a supercomputer packed with a million plugins, and then take full creative control of a recording project and, consequently, a big points-based slice of its profits, Albini used little gear, took a low fee, and let the band and their music do the talking. And if he could do it all in one take, so much the better.

In an industry famed for precise recording, a million vocal takes, and where a knowledge of Pro Tools shortcuts impresses more than ideas, this pioneering spIrit – or bloody-minded stubbornness, you decide – would earn Albini literally thousands of recording projects.

The only thing Albini shared with many other producers is that he set out wanting to make it big in his own band, the first of which was Big Black, which he formed in 1981. His musical cues and attitude stemmed from '70s punk and new wave, and the people who recorded it. He cited both the English studio engineer/producers John Loder and Iain Burgess as big influences on his own studio methods; Albini recorded tracks with both, and their ethos of capturing a band's live spirit would stay with him throughout his career, as would their attitude of using just a few choice pieces of recording gear that they knew inside out.

This was why Albini would later rail against using the computer in the studio. “No-one knows their computer software well enough to be aware of every single thing it does,” he told Sound on Sound in 2005. “In the analogue domain you know what you're supposed to do, you plug something in, and it's done.”

With this mindset, Albini would begin a hugely successful producer/engineer career in the late '80s including recording the 1988 Pixies album Surfer Rosa. Later milestones included Pod by The Breeders (1990), several tracks by The Wedding Present including 1991's Seamonsters LP, and PJ Harvey's second album Rid of Me in 1993. But it would be the same year's In Utero by Nirvana that would seal the Albini deal and give him a 'grunge' tag that would be hard to lose, but – eventually anyway – would lead to more work with everyone from The Auteurs to Page & Plant, Mogwai to the Jon Spencer Blues Explosions. In truth, the Albini sound was not so much grunge, but simply capturing the raw energy of a band, much of the time in his own Chicago-based Electrical Audio studio.

With his own music, Big Black would produce albums with titles like Songs About Fucking but this would be at the lighter end of the controversy scale, as Albini's next project was called Rapeman, and other band names he was associated with are simply unprintable.

Indeed, Albini was never far from controversy, and while his reputation in the studio was second to none, his attempts at provoking a reaction, either through his own music or in interviews, would often backfire. Those sympathetic to him would cite his ironic and twisted sense of humour, and also his passion for getting people to think. At the opposite end of the scale he was often caught up in racist or homophobic controversy where the 'ironic' label wasn't such a convenient get-out.

Albini later apologised for his outspoken statements, telling The Guardian, “the one thing I don’t want to do is say: ‘The culture shifted – excuse my behaviour.’ It provides a context for why I was wrong at the time, but I was wrong at the time.” And while you could put many actions down to naivety, or his punk attitude and provocative nature, Albini would also channel this rebellious side into doing good within what he saw as a corrupt music industry.

“The recording part is the part that matters to me. I take that part very seriously. I want the music to outlive all of us”

Not only did this manifest itself in his redefinition of the record production role into an engineering one, where he would help bands record rather than advise on creativity, but he would never agree to a slice of a record's points success that means so much cash for other successful producers. It meant that he lost out on some big numbers – somewhere close to $400,000 for the Nirvana album alone, according to some reports.

Albini's final band was called Shellac, with whom he recorded five albums, the last of which, To All Trains, was released just over a week after his death this year. He helmed thousands of projects over his four decade career – the maths suggests up to 4,000 – so it's fair to say that the pioneering maverick has left a huge mark on music, and it's a catalogue that will only be more appreciated as the years and decades pass. “The recording part is the part that matters to me,” he told The Guardian. “I take that part very seriously. I want the music to outlive all of us.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Steve Albini's production in four tracks

1. Pixies - Cactus (1988)

The Pixies album Surfer Rosa was very much Albini's big break, and Cactus sets a mark in the sand for the Albini sound. It's raw, it's in your face, it's sparse and it's over in two minutes. Move on! We love the story about why Pixies spell out the word 'Pixies' between verses too – they copied that from T-Rex who spelt out their name on the track The Groover. Bowie later covered Cactus on his 2002 album, Heathen, and spelled out 'David' in his version. Isn't music great?

2. Nirvana - Serve The Servants (1993)

If you think we should have included Heart Shaped Box from Nirvana's In Utero, then think again, as the band had it and other singles from the album remixed because they (or label DGC) weren't happy with Albini's versions. Serve The Servant was certainly single-worthy but escaped the remix treatment and is as raw and abrasive as the day it was recorded. And it was just one day, just one take in fact.

Albini later recounted how Kurt played the first chord louder than he had expected so it sounds very overdriven, but the band didn't mind and that one take is what you hear. That attitude got the entire album in the can in less than a week and then mixed in five days – what probably seemed like an eternity for Albini.

3. PJ Harvey - Rid of Me (1993)

Harvey chose Albini to record her second album because she knew what he did best was record a band like they are playing in front of you. No messing, no fills, just the band. This is the title track from Harvey's second album and pretty much sums that whole attitude and recording methodology, as if you are standing in the studio while Harvey sings and plays guitar, Rob Ellis drums and Steve Vaughan plays bass before you. Who needs effects, eh?

4. Mogwai - My Father My King (2001)

A 20-minute opus based on the melody from a Jewish prayer might not be your ideal party-starter, but Mogwai turn this into a wall of sound playing it live, and Albini was responsible for getting it onto tape – a lot of it – in 2001. Being the producer/engineer that he was, he made the final song from two earlier takes, splicing the tape old-school with a razor blade. Brilliant.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.

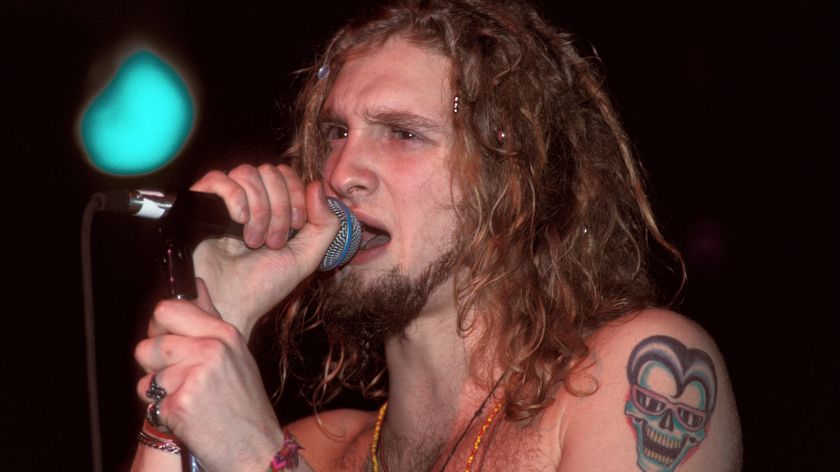

“Radio stations all said Layne’s voice is wrong”: Alice In Chains and Jane’s Addiction producer Dave Jerden helped to define the sound of alternative rock

“U wanna hear the raw files”: Producer Mike Dean tells streamers to switch off auto levelling on every music platform, and hear the music as it was meant to be heard

Most Popular