"Plugins get tricky because you start to hear with your eyes. Some of them have flashy interfaces - they make you think they’re doing more than they’re actually doing": St. Vincent on self-producing All Born Screaming

As Annie Clark releases her seventh album, Kate Puttick learns why the studio is both her heaven and her hell, and why there’s still a place for drum machines even when you’ve got Dave Grohl to hand

All Born Screaming is not just any old St Vincent record. The new 10-track release finds all-round musical powerhouse and global superstar Annie Clark on fire – both creatively, and in her press pics. The album marks the first time the Texan has sat alone at the head of the table with full production credits to her name.

Of course, it’s always been clear that Clark has considerable artistic chops from the moment she moved from backing band member of the Polyphonic Spree and Sufjan Stevens in their ’00s heydays, up the pearly staircase of fame to top charts alongside David Byrne, stand in for Kurt Cobain in Nirvana legacy shows and pen hits for Taylor Swift alongside star producer Jack Antonoff. All the while shredding masterfully as she went.

But up there in the big leagues, the noise can get loud. And putting herself back in the driving seat was an antidote for Clark.

“I think [taking on the producer role] was how I learned how to hear myself,” she explains. “It was something that I’d done on all of my records but I hadn’t been the main filter in the room and I know that emotionally there were places you could only find on your own.”

Clark continues: “Being an artist, that’s the main thing you want. If you’re a singer you want people to know it’s you just from one note. I wanted to have that same kind of recognisable voice as a producer. So I went all-in.”

Given the chance to chat to the busy musician ahead of her full promotional schedule – as well as a chance to preview All Born Screaming in all of its glory – we found an artist and producer at the height of her production powers. But, also, one who was more than willing to dig deep on her modular synth “sickness”, choosing between Dave Grohl and drum machines, and the importance of committing to a sound…

Studio heaven

The makings of Clark’s studio journey started in her early teens with a Tascam cassette 4-track. Her cheerleaders at the time were a computer-mad stepdad and her successful jazz duo aunt and uncle (aka Tuck & Patti, who have gone on to tour with her). Her weapon of choice back then was a PC-based recording system based around Cakewalk Pro Audio accompanied by plentiful outboard gear. Clark recounts happy days singing Billie Holiday melodies and practising guitar.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

People can do so much on their own in their bedrooms. I think that is so incredible

Fast forward to 2022, as she began to write this new record, fresh from the promotional cycle for Daddy’s Home, and the people she calls her “wrecking crew” of acolytes are somewhat different. To name a few, they include Welsh experimental songwriter and good friend Cate Le Bon, engineer Cian Riordan (with whom she worked on Sleater Kinney’s last album) and… rock royalty, Dave Grohl. The recording settings are somewhat grander, too: Electric Lady in New York and Steve Albini’s Electrical Audio in Chicago, as well as her own Compound Fracture studio in LA.

Whatever the location, it’s clear that Clark believes that a studio has a sacrosanct quality. Recording, for Clark, is an art that needs to be taken seriously.

“People can do so much on their own in their bedrooms. I think that is so incredible,” she tells us. “But I also think that the art of recording and the physics of doing things correctly or incorrectly, is its own thing.”

She breaks off to discuss the joys of deliberately blowing up an amp, before excusing herself for ‘riffing’ and returning to the point at hand.

Recording is the coolest. It’s so fun. There’s so many permutations. It’s fractal

“[In that case] you’re using tube distortion because you love the sound of it, and not necessarily just because you don’t know what you’re doing [with the amp] or you don’t know how to gain stage. I think it matters. Not in, like, a holy way, but… It’s a beautiful, amazing art, recording. Recording is the coolest. It’s so fun. There’s so many permutations. It’s fractal.”

She stops to cast around for an example. “You know, I’m looking at a mult right now. I’m looking at my patching. You could send that signal to three different places. What would happen if you did this? And what if you did that? I mean, it’s just thrilling.”

...and studio hell

Which brings us to our next question. Clark talks about the joy of recording. But she’s also described elsewhere how the experience of recording can be a version of hell.

“The hell part is sitting with yourself without getting anywhere,” she explains. “That’s the tough part, just in life. Probably only 3% of the music I made over the past three years is on this record. There have been hours and hours, tapes and tapes of just jamming alone in the studio. It might be 8am and I’m, like, making post-industrial music in my sweatpants. But eventually it becomes the song, and the things that lend themselves to a statement find their way.”

The muse, she explains, is a tricky bastard. “It takes a lot of finding it. I don’t know how everybody works, but in my experience, it’s not about having some exact idea and then, in a linear fashion, rendering that idea. You find it. The idea whispers to you from a corner and then you chase it and chase it. It disappears and then it reappears. Eventually, it reveals itself a little bit more.”

Of all of the tracks on this album, opener Heaven is Near caused Clark the most grief. “I wrote it on guitar, and so you can kind of hear the jangle. I love it on guitar,” she explains, “but it took a while to reveal itself.”

The problem wasn’t so much about a blank page, but fulfilling its potential. “I had written all the music and the melody and everything was, you know, more or less like it was a song. I knew what the chorus was, but I didn’t have the verses. I kept writing and rewriting the words. I knew what it, you know, was. The music was doing all the work, so the words just needed to be this impression, this feeling and get out of the way.

“Then singing it was another matter, because it changed the whole song. The music was [supposed to be] carrying the weight. So if you try to over-sing it, if you try to put anything on it that doesn’t feel completely true and real and beautiful and all those things, then it just crumbles before you. So, yeah, that one, I would say, was just a delicate little flower.”

Analogue witness

The empowering nature of having the space to engage in knob-twiddling at will was the rocket fuel for a lot of the songs on the new album.

“The modular world is a new world for this record,” Clark explains. “As an artist you have to find new tools. Things which inspire you. For this record everything had to be about electricity and circuitry; analogue and outboard. Things that were tactile and could only happen once. Lightning in a bottle.

Plugins get tricky because you start to hear with your eyes. Some of them have flashy interfaces and they make you think they’re doing more than they’re actually doing

“Songs like Broken Man are based on modular synth lines that I programmed.” She sings a fragment of the core riff. “That was modular. I was like, ‘Hell yeah – that lights me up inside! I’m going to build a whole song around that.’ Really, that was the genesis of a lot of these songs. The same thing is true production-wise. If there’s a tape warble, it’s because I ran it through tape and sped it up and slowed it down with my hands. Everything is very tactile, and intentionally so.”

Moving away from a computer-based setup was liberating for Clark. “Plugins get tricky because you start to hear with your eyes. Some of them have flashy interfaces and they make you think they’re doing more than they’re actually doing.”

Was the experience of working with analogue synths as satisfying as she’d hoped? “Working with actual electricity and circuitry, you have chaos,” Clark says. “You get a sound and try to get the same sound again, but it’s never going to be exactly what it was. Right? It’s chaos! In a great way. Modular synthesis is a sickness.”

A drain on the… brain? “And your pocketbook. But when it’s amazing, it’s amazing. And that’s why we become junkies for it. It’s really silly.”

Broken beats

From its opening track, with its stripped down, bodhran-like opening thuds, drums play a significant role in shaping the distinctive sound of All Born Screaming. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the premium class of drumming talent Clark had at her disposal, including Dave Grohl, Josh Fresse and Warpaint’s Stella Mozgawa.

As the album progresses, though, the acoustic drums give way to the synthetic pulse of a drum machine, most notably on the Prince-indebted Big Time Nothing. Clark rejects the premise of pitting human vs non-human rhythm makers against each other though.

Depending on the drum machine, it has a sting to it. That’s what we’re looking for. That’s why we love the sound of old-school MPCs

“Depending on the drum machine, it has a sting to it. That’s what we’re looking for. That’s why we love the sound of old-school MPCs – because, for one, they have a feel to them, but also because they have a sample rate and compression that does a particular, cool thing. So it has a soul.”

When it came to drum production, she explains, serving the song was the be-all-and-end-all. “Sometimes that’s a loop made by a drum machine, but you still have to make sure that the swing of the hi-hats is correct and that the feel is good. I like to run that through outboard effects and balance it all there and then. I’m a big fan of balancing in the machine. It’s the difference between building your house on sand or building it on rocks.”

That thought process informs how the rest of the track unfolds, she tells us.

“If you commit audio and say ‘this is the balance of these drums’ and print it, then you’re building a song that is based on a sound you actually, really, truly decided upon. Instead of taking everything and kicking the can down the road; [feigns befuddled voice] ‘Oh I’m not really sure if this hi-hat should be louder or softer, so I’m going to just record everything separately and then make that decision later.’ It’s like, ‘no, just make the decision’. Be bold, commit to a sound, and then you’re really building a house on rock.”

Is this approach of self-producing likely to be the blueprint for all St. Vincent records from now on?

As I make more music, I find it more mysterious, more mystical – to use a corny word. More than ever. But it’s true

“I love collaboration and I’ve been lucky to work with great collaborators in my life,” Clark explains. “So I would definitely do that again, just depending on the project. The difficult part about self-producing is that it’s just you. There’s only you to say, ‘yes, that is the best rendering of this vision that I can create squashing it, without overcooking it’. That’s the hard part, I would say. Not the technical stuff. It’s really just growing that extra instinct within you that’s like, ‘yes, this is it – let’s go’.”

It all comes back to, as she describes, “finding” the music. “As I make more music, I find it more mysterious, more mystical – to use a corny word. More than ever. But it’s true.“

All Born Screaming is out now on Total Pleasure Records.

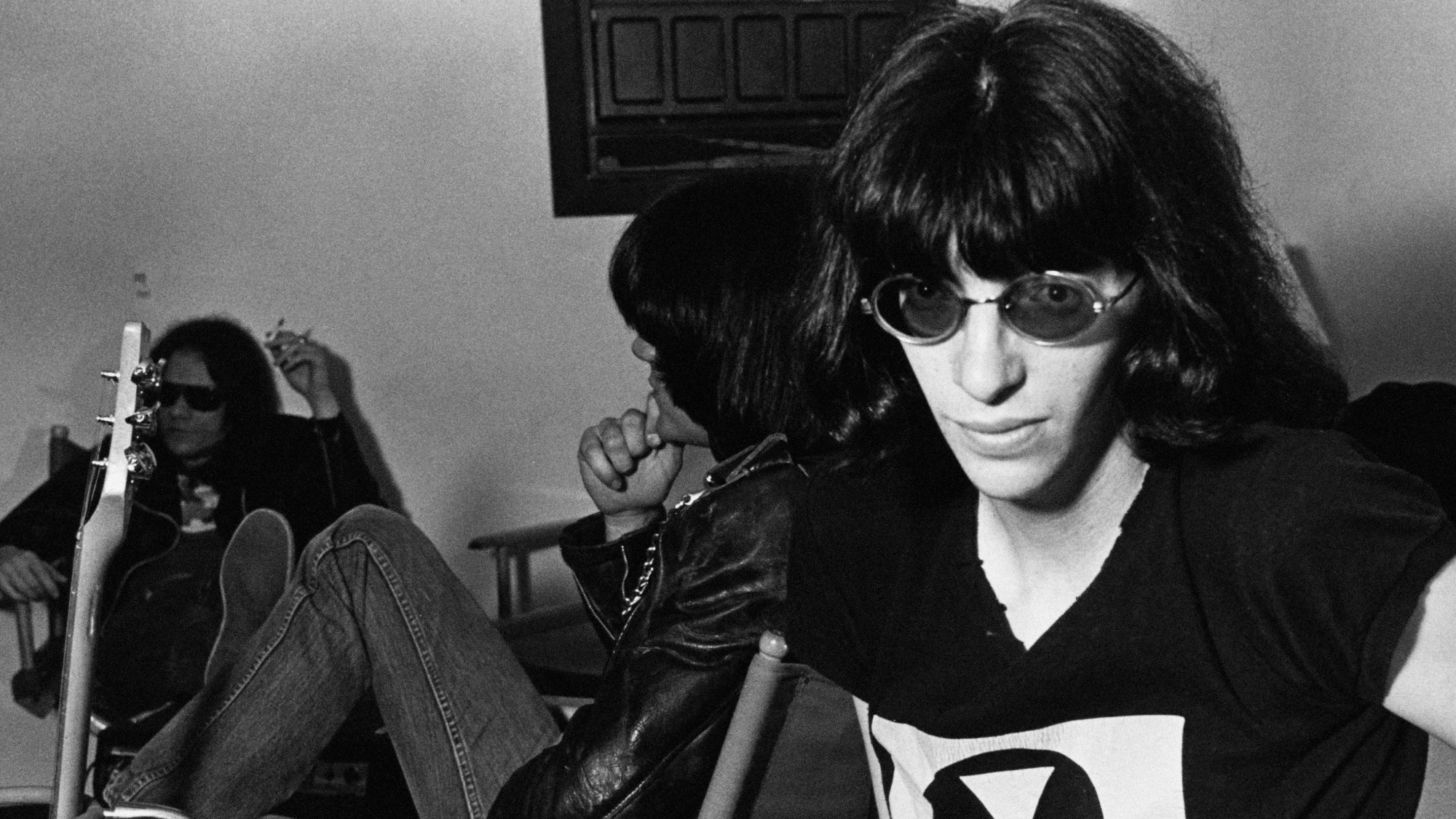

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track