Soundtracking secrets: How to get started writing music to picture

Writing to picture means responding musically to visual events on-screen. We explore some of the best practices that will serve you well during this process

In the hyper-fast world of film, television and video game development, composers rarely have the chance to live with a project for long periods of time.

More often than not, soundtracks are recorded during the final stages of production, and composers are enlisted to turn around their cues within the tightest deadline. A more music-centric project might involve a composer from the very early stages, allowing them to gradually develop themes and musical ideas that grow over time.

While that approach would be attractive for many, it’s not unwise for jobbing composers to already have banks of mood-aligned themes, melodies and cues ready-to-go. We’re going to assume you’ve accepted a more conventional film soundtracking brief for this first section.

Every element of your approach – what instruments are used, what genre you’re writing in and even how your material sits in the wider sound mix – needs to feed off the emotional content of the film.

5 absolutely free tools for soundtracking

For science fiction projects, electronic textures, synths and mechanical beats are likely going to be in play. For romantic films, you’ll likely find elements like sweeping strings, subtle piano and repeated ‘character’ themes. On the horror-end of the scale, just think of those sharp, unnerving stings, typified by Bernard Hermann and his violin-based orchestral tension.

Also, consider how nuanced sound design plays its part in contributing to the sense of dread. Some of the best soundtracks often delight in upturning the norms. But the principle is that the mood board is always set by the project. A composer’s job is to work for the film, heightening the emotions, major themes and momentum.

Once a composer has been hired to take on a project, the first step is to attend what is known as a ‘spotting session’ where the current cut of the film or TV show is played. During this process, the relevant creatives (normally the director, writer and/or producer) will discuss with the composer how they are imagining the music at this stage – there may even be a temp score in place.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

10 of the most incredible synth film soundtracks from Hollywood history

For composer Oliver Patrice Weder, head of music production at Spitfire Audio and a seasoned soundtrack composer, the spotting session often leads to a flurry of creativity; “[After the spotting session] I start with a first piece of music which perhaps could be called a suite; a piece that displays the overall mood, features all the instruments I might want to use and perhaps even a main theme.”

A virtuoso pianist, Weder builds his main melodic ideas using his core instrument: “A good tune is always a good tune, even at its bare bones. From there I start arranging with other instruments in line with the brief and creating variations of themes for respective scenes.”

Once a foundational piece or suite has been crafted and given the green light, then comes the trickier matter of fitting the tracks into the picture itself. Writing smaller tracks that reflect and build away from your main themes, moodier or more upbeat variants can give you wider musical clay to work with.

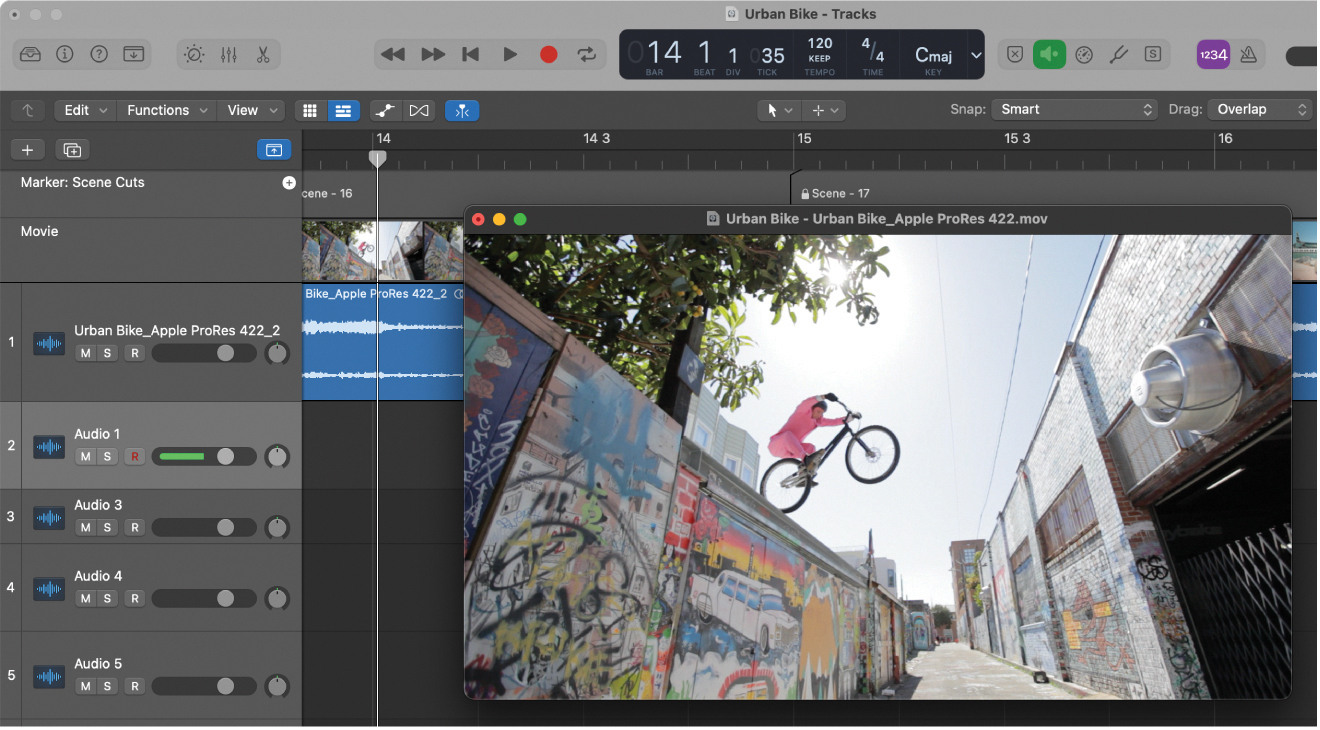

At this stage, it’s essential that you’re able to work within a DAW that is able to handle video capably and without lag. An established flagship in this regard, Steinberg’s Cubase (and its post-production-aligned sibling, Nuendo) is famed for its slick video incorporation, and a wide-range of tools designed to facilitate rigid writing to picture.

Synchronisation between audio and visuals needs to be firmly locked in-place, so have eyes on the video project’s SMPTE timecode so you know to the millisecond how to edit your cues.

Should there be any discrepancy with the audio/video sync due to your display settings, Cubase allows you to offset the timecode slightly (during playback only) as well as route different audio feeds to sync with the video projects. Other solid video supporting DAWs include Logic, Ableton Live, MOTU Digital Performer and Studio One 6.

With the project loaded up in your DAW, it’s time to write in earnest. It pays to keep those spotting session notes to hand, as well as any further insight from the creative team, and tonal indications from any temp track or suggested listening. That in mind, you want to infuse as much of yourself into the soundtracks as possible, so strike a balance between your own sensibilities and the needs of the project.

For the world’s most revered composers, of the ilk of Hans Zimmer, Hildur Guðnadóttir, Trent Reznor or Junkie XL, applying their personal stamp on the media is hugely important, regardless of the size of their teams.

“I want to be in control of every step of the process. When I can, I love to record the orchestra myself,” Junkie XL, aka Tom Holkenborg, told us recently. “I still mix all of my film scores by myself. I still master all my recordings myself, I deliver all these stems to the final product myself. I want to be in control as much as I can. Every step of the way I feel I can add more identity of who I am as a person.”

While Holkenborg is at the very summit of success as a soundtrack composer, the principle of being recognised for your particular style is key to ascending in the industry. Though you might not have the same wealth of resources as Holkenborg, don’t over-lean on existing soundtrack-tailored sounds, presets and libraries. Instead use them to complement your own sonic aesthetic, and build your own.

While there’s been a general trend towards subtler instrumentation and sound design-adjacent approaches, it helps to have at least a few core motifs to intersperse throughout the project. They might be character-aligned melodies, or phrases that reflect a bigger theme or smaller subtext. Either way, they’re powered by repetition, akin to a top-line hook in a commercial track.

The distinctive flavour of our soundtrack needs to work for the film, yes, but if your elements are consistently characterful, then they should be able to stand on their own two feet as a consistent piece. Think of the acclaimed soundtracks for films like Blade Runner, The Lord of the Rings trilogy and Soul – all captivating listens in their own right.

In the future instalments of our Soundtracking Secrets series, we’ll shed some light on the interplay between music and sound design, look at some essential libraries and tools that every working soundtrack composer should have to hand, and explore the balance between writing directly to picture and developing a library of ready to go cues for production music and sync purposes.

Learn from the best

We asked respected soundtrack composer Jonah Sirota what advice he’d give to anyone making their first start in the soundtrack composing world. “First, don’t underestimate the importance of staying up on technology and production techniques,” Jonah says.

“In soundtracking now, you are expected to be the one who knows how to deliver great-sounding files in the correct format and on time. I look forward to when I will have a team with a mixer, orchestrator, editor, copyist, recordist, and recording and mastering engineers. But for now with most projects, it’s on me to do all of that.

“The other thing is that, in this field, you can be called on to do any genre at any time. But that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t develop your own style, the thing you’re really good at. People will hire you because of what your music sounds like, not because you can throw anything together.”

It also helps to just be a friendly person to work with. Advice that Oliver Patrice Weder emphasises: “Keep your eyes peeled for opportunities, any kind. In the beginning, it’s important to throw yourself out there, take any project and network when you can. But above all, be nice and cool to work with.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.