Sound Of Metal’s Paul Raci: “Deaf people should be included... when you don’t provide a sign language interpreter at a venue, then you are being exclusive“

The Oscar-nominated actor and musician on deaf culture, performing Sabbath songs in American Sign Language, and why Sound Of Metal is a wake up call for musicians

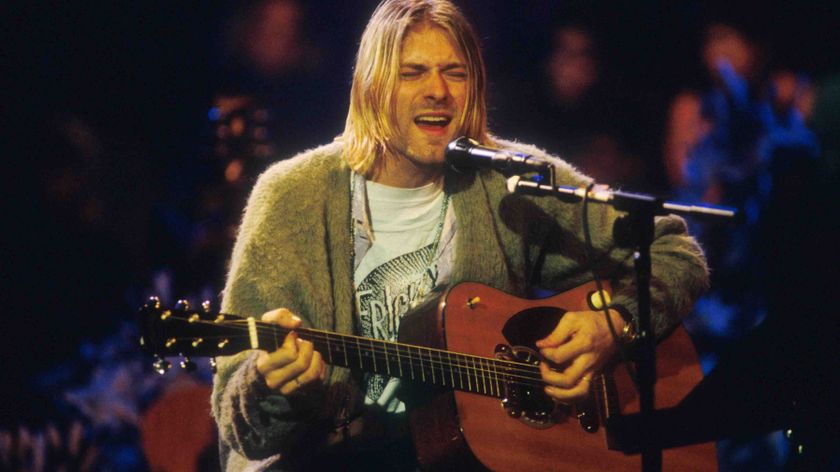

Sound Of Metal, the Oscar-winning drama directed by Darius Marder, tells the story of a drummer who loses his hearing. When the story introduces Ruben, played by Riz Ahmed, we learn that this has been coming for some time.

Ruben plays night after night in a metal duo with his girlfriend Lou (Olivia Cooke), touring the States in their RV, and when the moment arrives and his ears fail him, his hearing overwhelmed by ringing, it is harrowing. What does a musician do when they lose their hearing?

What Sound Of Metal reminds us is that they don't stop loving music, or needing music, and processing that loss – which is presented as a multi-dimensional grief writ large on Ruben's face – is a crucial step in adjusting to their condition.

My life has been the deaf community – my whole life. My parents were deaf. I went to Vietnam, came back an addict, and went through a lot of the things that you see in the movie

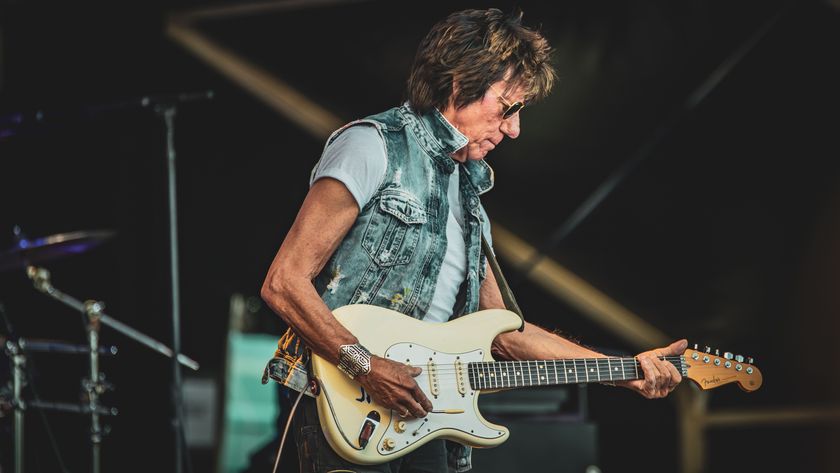

It's a scenario that Paul Raci knows well. A child of deaf adults, Rici is an actor and musician who fronts the Black Sabbath covers band Hands Of Doom and performs in American Sign Language. He has been around deaf culture all of his life.

In Sound Of Metal, he plays Joe, a grizzled and tough mentor at a home for deaf addicts. When Ruben checks in, it is Joe that has to help him find some equilibrium and a new sense of purpose.

Raci's still, authoritative and empathetic performance was nominated for Best Supporting Actor at the 2021 Academy Awards, and it is why he joins us to talk about the making of the film, and the lessons that Sound Of Metal has for anyone involved in music, either as a musician or a fan.

Congratulations on the film’s success, Paul. We often talk about actors being born to play certain roles but this really was the case with Joe. Surely you didn't need any persuading to sign on for the movie.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“No, when I first read the script, I knew that the guy knew what he was doing. I didn’t know it at the time but he had been researching for 12, 13 years, travelling across the country, interviewing different people, and actors, about what deaf culture was, so I could see that. I could feel that when reading the script.

“It didn’t take me long. My life has been the deaf community – my whole life. My parents were deaf. I went to Vietnam, came back an addict, and went through a lot of the things that you see in the movie. I have been involved with addiction ministries. I have been involved with [the] programmes. And I’ve been involved with rock ’n’ roll bands my whole life. It didn’t take me long to get the feeling for what it needed to do.”

Did Darius need to give you much direction? Because with your background, that authenticity is already there.

“He is such a sensitive man – and just a love bug! He’s a man of love, who walks the talk, and so he had a lot that he wanted to input into the movie that he had already understood about deaf culture, but with the understanding that he always knew that he was still on a learning curve during the filming.

This is a good note for any musician or any actor, or director – be collaborative with your team. That’s gold right there. That’s where you find the gold

“He was still learning things about deaf people and about deaf culture while filming. You can’t just jump into another culture – and I am talking about any culture – and say, ‘Hey! I’ve been studying this. I am one of you now.’ He never, ever had that attitude. Did he give me direction? Yes, as far as feeling and tone, and I would then also give him my feeling back about how things were striking me. It was very much a collaborative effort.

So it could be a two-way street when working the scenes?

“In in the beginning he said to me, ‘Look, I am not Shakespeare, so if you feel like something could be changed in the lines, by all means, let’s do that.’ And we did. We did a lot of improvisation, in the moment… On film! Remember, we only had about two or three takes for each scene. This was not a big-budget movie, like, ‘Okay, take 15. Boom!’ It was two or three, and let’s move on.

“The fact that we're doing improvisation with just a little amount of time, and on film, it was incredible the things he captured. This is a good note for any musician or any actor, or director – be collaborative with your team. That’s gold right there. That’s where you find the gold.”

On this set, Sound Of Metal, everybody wanted to be here. The guy doing the sound, the makeup people – this was a special, special thing happening. And I felt that. When you watch the film it just comes through

Smaller pictures with smaller sets can allow for that, can’t they? They can allow for little moments of magic.

“Yeah, and the stakes are higher. On this set, Sound Of Metal, it was like, ‘Every second counts. It’s special. This is wonderful. This is a blessing to be here.’ Everybody wanted to be here. The guy doing the sound, the makeup people – this was a special, special thing happening. And I felt that. God! When you watch the film it just comes through, because everybody involved in it felt that way about this movie and the work.”

Absolutely, they all own it. From the grips to the leads.

“Everybody owns it. Yeah.”

You are not in this particular scene but your perspective on it would be great. It's a very powerful scene and has Ruben on the slide with one of the kids from the group, and they are communicating through a simple rhythm. That feels like the essence of the movie – just because you have lost your hearing doesn’t mean you have stopped loving music.

“You are right about that scene. It’s beautiful. It’s perfect. My mother lost her hearing at the age of five years old, from spinal meningitis. My father lost it when he was a baby, so he never remembered hearing. But my mother, at five? When you look at a five-year-old child, they have acquired language. They know music already, and to have that taken away is very, very disturbing, tragic, just as you see in the movie.

“To your point about that slide scene, my mother never lost her love for music. She bought me my first guitar. She sent me to the Beatles, bought me my ticket to go see the Beatles when they came to Chicago.

“When I made my first recording, a little 45-rpm, I brought it home and put it on the record player, and my mom took her hand and put it on the record player to feel the vibration. It was such a touching moment, just like in the movie. She put her hand on that Motorola and she looked up at me and she goes, ‘It’s good.’

It is an important point to make – that just because people have lost their hearing doesn't mean they have lost the love for music.

“You don’t lose it. Music is an energy and it doesn’t matter. Hearing people say, ‘How can these deaf people understand the show when they come to a rock club?’ They’re up there, at the front of the stage, and they’re feeling the vibrations. They are seeing the prolific lyrics of Geezer Butler coming off these hands here, and they love it. Music, once you have acquired it, you cannot lose it, and that includes deaf people.

My mother never lost her love for music. She bought me my first guitar. She sent me to the Beatles, bought me my ticket to go see the Beatles when they came to Chicago

“So, there he is, communicating with this kid on a slide, and this kid is deaf at a young age, but he feels the rhythm. He feels those drums speaking to him. That is an incredible scene. I agree with you. I don’t care if I am not in it but it is one of the most powerful scenes I have ever seen. It just shows you what my mother’s experience was, emotionally. Thank you for bringing that up because that just reminds me of how powerful that is.”

How can we enhance the musical experience for those with hearing loss?

“This is a good opening to peak the awareness of the rest of the world – or the hearing culture, as I call it – know that being deaf doesn’t mean you’re dead. They’re not dead. Emotionally they are super alive. All their other senses are heightened, and they want to be involved in pop culture.

“They want to know what the Foo Fighters are talking about. They want to know why Sabbath were so prolific. What is it about that? So when they see me with a headset on, signing these lyrics, it is like a whole new world. It’s like, ‘Ah, so that’s why you hearing people are going so crazy. That’s what it is?’

“Deaf people should be included. Right now, I keep talking about inclusivity, and when you don’t provide a sign language interpreter at a venue, for a band that doesn’t do sign language, then you are being exclusive – you are not including people who may want to come in and check out what’s going in there with this group of people.

And that is what music does, it brings people together...

“This hearing culture and this deaf culture can maybe intersect. What’s wrong with that? That’s what we need, and that’s why I think this movie can be a real uniter, to let you know that, Ruben loses his hearing, he meets a young deaf kid, and yet they are going through the vibrations of musical language to communicate. That is a beautiful thing and we could see more of it.

“Of course, my band need no interpreters onstage ‘cos I’m doing it but every other band out there, who’s doing it? Nobody. And there are so many great bands out there. I was just talking with a guy from Rock Sound and he was saying he saw a Green Day concert with a sign language interpreter. That’s insane! That’s beautiful. Green Day is a perfect band to interpret for deaf people.”

Deaf people should be included. Right now, I keep talking about inclusivity, and when you don’t provide a sign language interpreter at a venue, for a band that doesn’t do sign language, then you are being exclusive

And Sabbath are perfect for ASL, too. Look at Ronnie James Dio– his style was very visual, with so much information imparted visually even before you hear a note.

“Yeah, and the energy he had, the energy that all these guys had – every guy who was ever in that band… You didn’t go just to hear the lyrics. You went there to be a part of this occasion, this experience, to feel that energy, and then hold onto it as long as you could until the next concert. That’s the way I looked at it. I had to hold onto it.

“When you see the lyrics come alive, and they are talking about God, about nuclear destruction, the devil. Oh my God, there were so many things that they were talking about. I am so fortunate to be able to do this stuff in sign language. I think that it has added years to my life, to be able to keep on doing it, yeah, years onto my life.”

You are incredibly still as Joe. Can you talk a little bit about the differences between this performance and your theatre work.

“Thank you for that, man. This is my first big movie. I have been doing theatre for 35, 40 years, in small, 100-seat houses. One hundred people! I’ve had bigger audiences in rock clubs than I have had in some of these theatres! [Laughs] But with the theatre, it is a very intimate space, and you can be very real. I hadn’t done theatres where there were 300 people. With 99 seats, you can afford to be close and intimate, and very quiet, and for this film, that is what it had to have.

Doing what I did on this film is no different to anything I have ever done in a small, 99-seat house. Same technique

“Fortunately for me, I had a lot of time to meditate. I had a lot of time to be still. As Joe talks about, the stillness. That is my thing. That’s my whole thing. Reading the script? ‘Oh my God, I know this man.’ By the time I got to the set, doing what I did on this film is no different to anything I have ever done in a small, 99-seat house. Same technique. I never had to act very big. I’ve never had to do all that. I’ve always been a small type of actor, so coming to film was perfect. That’s all I had to do.

“For an actor who has done movies all his life, it’s very difficult for him to go onto a stage, but an actor who has done stage, equity theatre, the transition to film [clicks fingers] is not that difficult. I always say those pretty boys who do these movies, come do some 99-seat theatre, man, you ain’t gonna last a week! [Laughs]”

And meditation was key?

“I had to make sure that I had my meditation time in the morning, that I was settled, that I felt like Joe felt, so that I could talk that talk. Fortunately for me I had the time to do that when we were filming.“

Cinema is the perfect medium for this story. The sound design is wonderful, of course, but cinema started as a silent medium, where everything was visual, and with the art form in such a state of flux, maybe it is an opportunity to return to those fundamentals. Maybe it is time we see a whole film in ASL?

“Maybe we should. And I know a lot of deaf actors who are trying to get things accomplished, so whatever I can do to help them I am going to do that. But you are right. Film is in a constant state of flux. I love going back to those silent films because my father who is totally deaf loved Buster Keaton. Loved him! More than Charlie Chaplin. He loved the pathos in his face. My father just loved that man.

“And when you see the talkies start in film, and how acting changed, to this weird kind of acting, it is fascinating. The way acting is in film now, it was the perfect mode for Sound Of Metal. It really strikes your heart. I especially hope people can go and see it in the cinema because to see it on a small screen is okay, but if you see it in a cinema it will strike you again and again and again.”

High-profile cases like AC/DC’s Brian Johnson draws some attention to the issue but do you think the music industry supports artists enough with hearing loss?

“I don’t know. Nobody ever does enough, but I would be remiss to say. They are doing what they can when they are reminded of it. So here is a little reminder, Sound Of Metal! Just to remind you there are deaf people who care about music. There are a lot of us musicians who suffer from tinnitus.

Musicians are more and more aware that they should protect their ears, and we have got these gadgets now that do that. Protect yourself. You don’t want this to happen to you

“When you think about it, in the ‘70s, I was doing hard rock, and we did not have protection for our ears. We did not have these little Eargasms [high-fidelity earplugs] that you put in your ears to protect you. That is a thing that we should be aware of. Musicians are more and more aware that they should protect their ears, and we have got these gadgets now that do that.

“But poor Brian. I mean, you think about when he was doing it in the ‘70s, there was no protection. I don’t know how the man made it through, so my hat is off to the man. I know a bit of what he is going though; he is going through what the character Ruben is going through in the movie. [Ruben’s] is a very severe loss, and it’s devastating.

“There are a lot of musicians out there who are having this devastating experience. If we can just talk about it like we are now, you and I, we can make people aware that this is a problem, that there are musicians out there who are suffering because of it. We should be aware. Protect yourself. You don’t want this to happen to you.”

There is a preconception in rock circles, that because it has got to be loud, that protection is somehow diminishing the experience.

“Rock ’n’ roll has always had that devil-may-care, ‘We’re young! We’re indestructible.’ I felt that way. Everybody feels that way. But I think it is just my job as an elder statesman of rock ’n’ roll, if you will, ‘Dude! Protect your ears!’ Because you want to keep using this precious sense that you have. And believe me, I know so many people who are suffering from that right now, making the transition to what Ruben is doing.

As a musician, hearing loss scary, but it is something that has to be addressed. I want to bring that awareness to everybody

“As a musician, it’s scary, but it is something that has to be addressed. I want to bring that awareness to everybody. We don’t have labels on us that say, ‘Hey, I’m deaf.’ People who are having hearing loss and stuff like that, you don’t see it, you don’t know what the guy next to you is going through.

“It’s out there and you need to really take control of your own life. You go to a concert, a small club, there are devices. They are very simple. You put them in your ear; you can still hear everything. It is just blocking out that destructive pounding that your eardrums are taking.”

- Sound Of Metal is out in UK cinemas now and streaming on Amazon Prime

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“If you want a good vocal, you gotta drink snake sperm”: Singer Jessica Simpson reveals the unusual drink that keeps her vocal cords in tip-top condition

“I was thinking at the time, if anyone wants to try and copy this video, good luck to them!”: How ’60s soul music, African rhythms and a groundbreaking video fuelled Peter Gabriel’s biggest hit