Smoke On The Water at 50: The story of Deep Purple Mk II and the most famous guitar riff of all time

Between 1969 and 1973, Deep Purple’s MkII incarnation took on the world then tore itself apart. This is the story of the axe fights, smashed Strats, neo-classical solos and power struggles behind British rock’s most dysfunctional family

London 1969. There’s something in the air. Flower power has wilted. The rock scene is sprouting chest-hair and testicles. Zeppelin are already out of the blocks, Sabbath are on their heels, and at a low-key club gig in June, Deep Purple’s guitar wizard and dark lord, Ritchie Blackmore, is head-hunting the final members for his near-mythical Mk II line-up.

Given the animosity that would later derail the band’s four-year run, perhaps it’s apt that bassist Roger Glover sensed a malign presence in the crowd as he and vocalist Ian Gillan performed with doomed outfit Episode Six that night. “These two shadowy figures arrived,” he recalled in Classic Rock of Blackmore and Purple organist Jon Lord. “I remember being rather scared. They were very dark, broody sort of villains. I felt they were from another world, not mine.”

Purple had already chewed up original singer Rod Evans and bassist Nicky Simper: the first casualties of Blackmore’s Machiavellian quest to create visionary rock ’n’ roll at any personal (or personnel) cost

Deep Purple wasn’t the kind of gig you passed up. Glover and Gillan duly signed contracts at the band’s London offices on Newman Street, but surely not without trepidation. Formed in Hertfordshire in 1968, and firing out three unfocused albums within a year, Purple had already chewed up original singer Rod Evans and bassist Nicky Simper: the first casualties of Blackmore’s Machiavellian quest to create visionary rock ’n’ roll at any personal (or personnel) cost. As Gillan and Glover would discover, the door swung both ways.

This is gonna sound cocky, but I think I can improvise better than any rock guitarist

Ritchie Blackmore

Blackmore’s reputation for rolling heads was matched only by his legendary talent. Even in the golden age of the guitar hero, the so-called Man In Black was a cut above, with god-like touch, shred-worthy speed, an ear for inspired harmonies and a flair for improvisation that makes 1972’s Made In Japan a front-runner for hard rock’s best live album. "This is gonna sound cocky,” he once shrugged, “but I think I can improvise better than any rock guitarist.”

Blackmore was a thrilling contradiction. Schooled in blues rock from his session days, yet steeped in classical theory; soft-spoken in person, but prone to smash his Strat into splinters; a stinging rock player who would routinely jam Greensleeves onstage. “I’m interested in extreme rock ’n’ roll,” he told Trouser Press. “At the other extreme, I’m interested in medieval modes… sitting in a park playing little minuets. “I just think there’s such a poor standard in rock ’n’ roll,” he added. “It’s disgustingly low.”

Under Blackmore, you kept up or got run down. For now, with Gillan’s silver-lunged shriek, Glover’s grooves, the world-class drumming of Ian Paice and the sinister Hammond lines of the classically trained Lord, the guitarist had his dream team. “It was because of all the bands we’d been in before,” says Gillan of Mk II’s widescreen vision. “It was rock ’n’ roll, but it came out in a beautifully expressive way.”

“In the beginning,” Blackmore recalled, “Jon was writing most of the music and I’d throw in some riffs. We kind of flim-flammed around before we found Ian and Roger. But it wasn’t until Led Zeppelin came along that we really had a direction. We thought, ‘Wow, that’s the type of music that we want to play’. Really heavy rock.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

I remember Ritchie saying, ‘If it’s not dramatic or exciting then it doesn’t have a place on the album’

Roger Glover

But first came 1970’s Concerto for Group and Orchestra: a three-movement concerto, written by Lord and recorded with the Royal Philharmonic, that proved a false start and a bone of contention. “It really got up Ritchie’s nose that Jon was being hailed as the main composer and leader of Purple,” recalled Glover. “The more publicity Concerto received, the more resentful Ritchie became.”

“I wasn’t happy with it,” Blackmore confirmed. “I said to Jon, ‘Look, let’s give this heavy, riffy rock a chance, and if it doesn’t work then I’ll play with orchestras for the rest of my life’.”

As ever, Blackmore got his wish. If Led Zeppelin I threw down the gauntlet in 1969, then 1970’s Deep Purple In Rock knocked it out of the park. Recorded in bursts between touring, this album unveiled the hard, fast, feral Mk II sound, and was good enough to justify grandiose sleeve art featuring the band’s faces grafted onto Mount Rushmore.

“We had a determination to put, once and for all, our stamp on what we were,” says Glover, “which was a rock band, and not a classical, pseudo-artsy progressive band. I remember Ritchie saying, ‘If it’s not dramatic or exciting then it doesn’t have a place on the album’.”

Even without the classic Black Night single – also released in June 1970, but inexplicably left off the album – Deep Purple In Rock was a juggernaut. Speed King kicked off with a whammy freakout, savage riff and harmony solo. The epic Child In Time spilled from soulful bends to machine-gun picking on a Gibson ES-335.

Blackmore later recalled he “went crazy” with his whammy, even smashing his guitar against the control room door during the solo of Hard Lovin’ Man. “It was balls to the wall,” says Glover. “It was a feeling of playing your instruments to the utmost.”

Nobody ever ‘wrote’ a song. Speed King, Child In Time… none of those songs were written. We jammed them

Ian Gillan

In later years, Blackmore would claim he “did most of the riffs and progressions”, but split the writing credits five ways to avoid friction. Gillan disputed this: “Nobody ever ‘wrote’ a song. Speed King, Child In Time… none of those songs were written. We jammed them, and eventually it happened, and so you’d groove, and you’d end up with seven-minute songs and nobody gave a damn. It was quite revolutionary.”

In Rock hit UK No 4, and established that the new line-up could break jaws and shift units. With the label wanting more, Lord recalls the band decamping to a “derelict, damp, slightly haunted place down in Devon” to start 1971’s funkier long-player Fireball. Bad vibes and behaviour abounded, most spectacularly when Blackmore chopped down Glover’s door with an axe after freaking out in a séance. “Ritchie was a mysterious presence,” said the bassist. “A thorny one. He was always ready to express his barbed wit and do outrageous things.”

Musically, they held it together. With Blackmore switching from Gibsons to his trademark Fender Strat, Fireball has some scorching moments, not least the clipped funk riff and spacey solo of No No No. But it was disowned by the band, and especially the guitarist. “I don’t even own Fireball,” he said. “I didn’t like that at all. It was done under duress… and we were in the studio for five minutes at a time.”

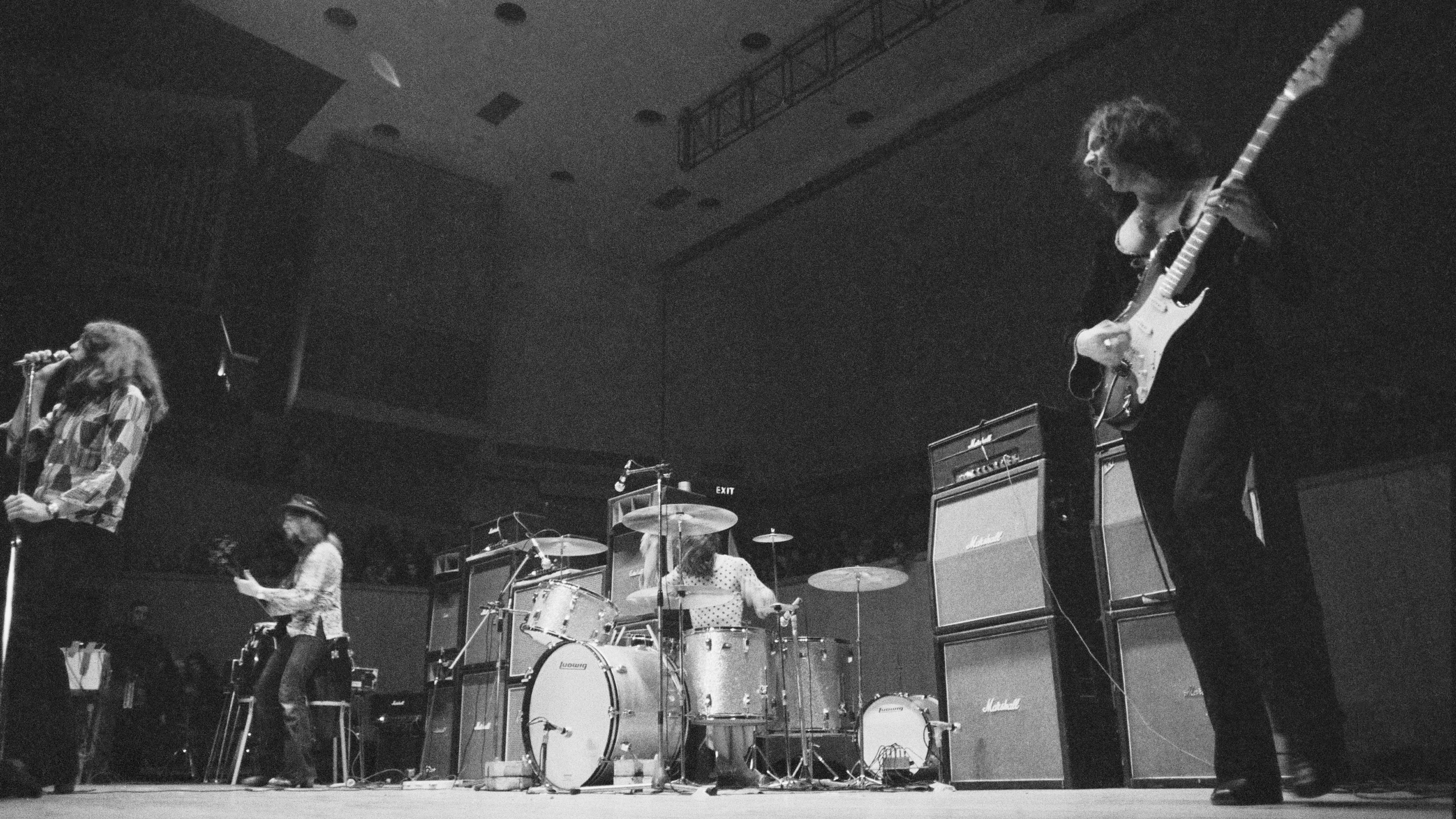

Doomy, dark and dangerous: not just a reasonable summary of Ritchie Blackmore, but also of his early-70s tone. Although he can be seen playing a Gibson ES-335 in 1969’s Concerto footage, from 1970 onwards, his preference became a Fender Strat with a scalloped fingerboard, run through Marshall Major 200-watt heads (modified with an extra output stage), spiced up with a treble booster and wah, and played so hard that he frequently snapped the whammy.

"It’s much easier to flow across the strings on a Gibson,” he once noted. “Fenders have more tension, so you have to fight them a little bit… but I stuck with the Fenders because I was so taken with their sound, especially when they were paired with a wah-wah.”

By Gillan’s admission, Deep Purple needed to “get back to doing that rock stuff”. Smart move. The legendary Machine Head album was due to be recorded at the Montreux Casino in Switzerland at the end of 1971, but when the venue burnt down that December, it both inspired the lyric to Smoke On The Water and forced the band to set up the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio at the closed-for-winter Grand Hotel. With the band squatting in a corridor off the lobby amidst a spaghetti-junction of cables, the conditions were hardly befitting of rock royalty, but with Purple’s hatchets temporarily buried, they blazed through their strongest material to date.

Guitar shop mainstay Smoke On The Water is a no-brainer (much more on that later), and the rocket-fuelled R&B solo of Lazy is pure soul, but just as potent is Highway Star, with the clickety-clack riff written by Blackmore while “dicking about” with his banjo on the tour bus. It’s notable for one of his few preconceived solos, fusing blues, major, minor and diminished scales, and arguably lighting the fuse of the neo-classical style. “The guitar solo is just arpeggios based on Bach,” he once shrugged.

By contrast, the chorus riff to Space Truckin’ was brilliantly bone-headed. “I came up with this riff… it was almost like a thumb exercise,” recalled Blackmore. “I took it to Ian Gillan and said, ‘I have this idea, but it’s so ridiculous… it’s so silly and simple, I don’t think we can use it’.” They did, and it became a standout of Purple’s undisputed masterpiece. In April 1972, Machine Head topped the UK album chart, later hit US No 7, and has long since passed into the hard-rock canon, but Mk II would never be so productive again.

While the band’s chemistry had been semi-playful during recording – with each member competing to make their instrument loudest in the mix – the mood turned poisonous by 1973’s Who Do We Think We Are. With royalties flowing, the band worked from a luxuriousItalian villa, but Glover recalled “lounging by the pool” while waiting for Blackmore to emerge from his accommodation.“We’d become a fractured family, really,” he said.

What I didn’t realise was that behind us was a big drop of about 15 feet and Gillan fell down and crunched his head

Ritchie Blackmore

Nobody was safe from the chop. While Concerto had seen a power struggle between Blackmore and Lord, as Mk II evolved, what Glover called the guitarist’s ‘evil eye’ had turned onto Gillan. As early as 1970, the friction was palpable, exemplified by the half-accident in a Paris nightclub that October, when Blackmore moved Gillan’s chair as he sat down. “What I didn’t realise was that behind us was a big drop of about 15 feet and Gillan fell down and crunched his head,” Blackmore noted. “After that, he was never the same.”

Now the fractious relationship was openly disintegrating. “It was painful,” reflected Glover. “The division between the two was there for all to see. Purple as a band has always – I was going to say ‘thrived’, but that’s not the right word – on the terrible clash of personalities between Ritchie and Ian.”

One by one, the wheels fell off. By 1973, Gillan had given his notice, Blackmore was planning his own exit (taking Paice with him), and Glover was on borrowed time, frozen out and in the dark until manager Tony Edwards confirmed his fate. “He shrugged: ‘Well, they want you out of the band’,” recalled the bassist. “‘Ritchie’s agreed to stay, but only if you leave’. Unbeknown to me, they’d been checking out this other bass player, Glenn Hughes. Later, Ritchie told me, ‘By the way, it’s not personal, it’s just business’. At least he was being honest.”

I sat with Ritchie as he played the solo [for Hold On]. He didn’t give a monkey’s arse about it

David Coverdale

Following Gillan’s 1973 swansong in Osaka, Mk II became Mk III, as Hughes and David Coverdale hit the ground running. While commercial success continued with 1974’s funkier Burn, Blackmore cut a troubled figure, watching his marriage dissolve, squabbling over the royalties split, and feeling his band wrestled away by soul-boy Hughes.

The guitarist dismissed the new Purple sound with the disparaging tag ‘shoeshine music’, and supposedly made little effort on 1974’s Stormbringer. “I sat with Ritchie as he played the solo [for Hold On],” recalled Coverdale. “He didn’t give a monkey’s arse about it.”

5 songs guitarists need to hear by… Ritchie Blackmore (that aren't Smoke On The Water)

Accordingly, press and public didn’t give much of a monkey’s arse about Stormbringer, and although Blackmore promised a harder follow-up, it never happened, as the maestro quit during the 1975 world tour to form Rainbow. “Seven years is long enough,” he said. “I thought the band was on the decline.”

To conclude, a few statistics. Deep Purple have existed since 1968, released 22 studio albums and turned over 13 band members, including touring musicians. As you read this, they are alive, well and preparing to perform watertight readings of the hits in an arena near you with the fabulous Steve Morse. For all that, there’s an argument that Britain’s greatest hard rock institution never topped that early-70s run, even when the Mk II members reconvened in the 80s (“There wasn’t that sense of camaraderie we’d had before,” admits Gillan).

No kidding. With grim inevitability, the line-up splintered again – twice – and by 1993, Blackmore was appearing on Swedish TV threatening to batter Gillan in a back-street (“He’s probably a better fighter, so I’m going to do it with a few friends of mine”). In 2006, Gillan was similarly combative: “Ritchie Blackmore? No, I don’t speak to him at all. That asshole – I will never speak to him again.” It’s pretty conclusive. So don’t sit waiting for hell to freeze over. Instead, grab your copies of In Rock, Fireball and Machine Head, and enjoy the dark majesty of hard rock’s most formidable line-up performing at full-throttle.

Ian Gillan tells the story of Smoke On The Water

Come on, be honest now. As a guitarist, there’s an odd-son chance that at some point, you’ve found your fingers wrapping themselves around Ritchie Blackmore’s iconic Smoke On The Water riff. And who could blame you? The fifth track on Deep Purple’s majestic 1972 album Machine Head holds at its heart one of the most recognisable and oft-played riffs in rock ’n’ roll history. Solid, simple and catchy as hell.

But if it hadn’t been for the fateful night of 4 December 1971, Smoke On The Water may never have reached the wider ears of the world. That month, Deep Purple had relocated to Montreux, Switzerland, to lay down their sixth album. This would be the third to feature the stellar ‘Mark II’ line-up of vocalist Ian Gillan, bassist Roger Glover, drummer Ian Paice, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore and keys player Jon Lord. The band thought that London’s traditional studios were too dry-sounding, and instead hotfooted it to the Alps, with the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio in tow.

Purple planned to profit from “the big ambient sound” of the Montreux Casino’s concert hall, run by their promoter pal Claude Nobs.

The day after the guys arrived, they trooped over to the casino to catch Frank Zappa And The Mothers Of Invention play the final show of the season. Disaster struck but, in tragedy, the band found inspiration.

The downdraft from the mountains caused the smoke to blow across Lake Geneva, like a film set or dry ice on a stage show. At this point, Roger wrote the words ‘smoke on the water’ on a napkin

Ian Gillan

“I was in the hall during the performance, particularly enthralled with the contributions of Flo and Eddie [ex-Turtles members and Mothers Of Invention backing vocalists], who were sounding just wonderful, when I heard two pops over my shoulder as a flare gun was fired high into the wall on stage left,” says Ian Gillan. “There was a lot of fizzing and sparks as the fire took hold in the wooden service trunking. Frank stopped the show and got everyone to leave.

"Claude Nobs went down to the basement and pulled out some kids that had run in there to escape. We all moved away from the scene to the Eden Palace au Lac Hotel, where we stood in the bar and watched the place going up in flames. The downdraft from the mountains caused the smoke to blow across Lake Geneva, like a film set or dry ice on a stage show. At this point, Roger wrote the words ‘smoke on the water’ on a napkin.”

Claude Nobs soon found Purple a new recording venue at the Pavilion theatre but, after widespread complaints about the noise, the group were forced out by local police and duly set up studio shop at the Grand Hotel.

“We had to make it up as we went along,” explains Gillan. “I remember equipment being set up all over the place to get some separation without us turning down. It was surreal when I think back but normal at the time. You did what you had to do. The truck was too far away and it was bloody cold so no one was keen to listen to anything until we felt it was right.”

It was just another riff, like Into The Fire. We didn’t make a big deal out of it and it wasn’t being considered as a track for the album

The backing track to Smoke On The Water was one of the few things actually laid down at the Pavilion before Purple were kicked out and, unbelievably, the music was simply part of an elongated live band jam used to balance the recording equipment.

“It was just another riff, like Into The Fire,” says Ian. “We didn’t make a big deal out of it and it wasn’t being considered as a track for the album. It was a jam at the first soundcheck. We didn’t work on the arrangement – it was a jam. Smoke only made it onto the album as a filler track because we were short of time. On vinyl, 38 minutes was the optimum time if you wanted good quality – 19 minutes per side – and we were about seven minutes short with one day to go. So we dug out the jam and put vocals to it.”

Being the last track, there was plenty to write about

Ian Gillan

Ritchie Blackmore played his Strat on the jam that would become Smoke On The Water and was plugged into – as far as Gillan recalls – “a Vox AC30 and/or a Marshall”. When the band decided that they were going to include Smoke on the LP, they quickly had to pen some lyrics and record a few quick overdubs, including Gillan’s lead vocal and Blackmore’s solo.

“I can’t remember the solo being recorded but it’s very good – full of character and technique, normal for Ritchie,” explains Gillan. “[Writing the lyrics] was easy! Being the last track, there was plenty to write about. It ended up being a biographical account of the making of the album Machine Head. ‘We all came out to Montreux…’ and so on!”

The Machine Head album, released in March 1972, would further enhance Deep Purple’s reputation as one of the greatest – and heaviest – British bands on the planet, hitting No 1 in the UK and an unprecedented No 7 in the USA. Smoke On The Water was eventually released as a single in 1973, scoring Deep Purple their second (and last) Top 5 hit in the States.

Smoke would, of course, go on to become one of the most covered songs of all time, but does Gillan have a favourite version? “I have two,” he reveals. “The Firemen Of Edo, and Yvonne The Tigress. I have the cassette tape at home and witnessed a performance of Smoke in a samba style by this South American stripper. It’s also the only time I’ve heard an audience in a strip club chanting, ‘Get ’em on! Get ’em on!’”